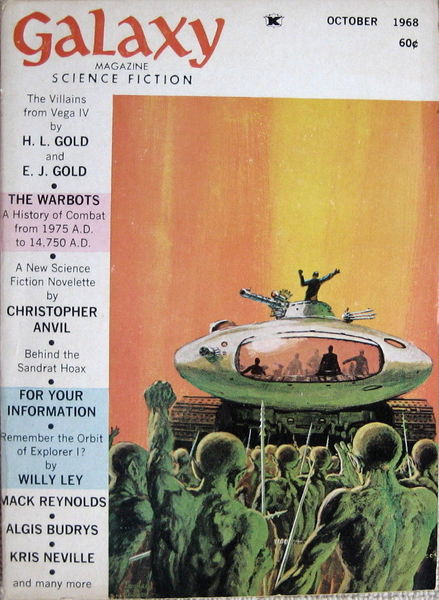

Galaxy, October 1968: A Retro-Review

|

|

An issue of Galaxy from fairly late in Fred Pohl’s tenure. There’s one fairly notable story here, and a couple more good ones, but to me the most interesting feature was Algis Budrys’ book review column.

But let’s begin at the beginning. The cover is by Douglas Chaffee. Interiors are by Jack Gaughan, Joe Wehrle, Jr., Dan Adkins, Virgil Finlay, Larry S. Todd illustrating his own piece (not surprising, as Todd, then just 20, became fairly well-known later for his comics work), and two artists whose full names I didn’t know: Brand and Safrani. Buddy Lortie identified them for me: Brand was Roger Brand, a fan artist who became a pro, and did comics work as well; and Safrani was Shehbaz Safrani, who seems to still do fine art. I should note that the magazine was very thick in this era — 196 pages (including covers). My copy has staples: I don’t know offhand if that was normal.

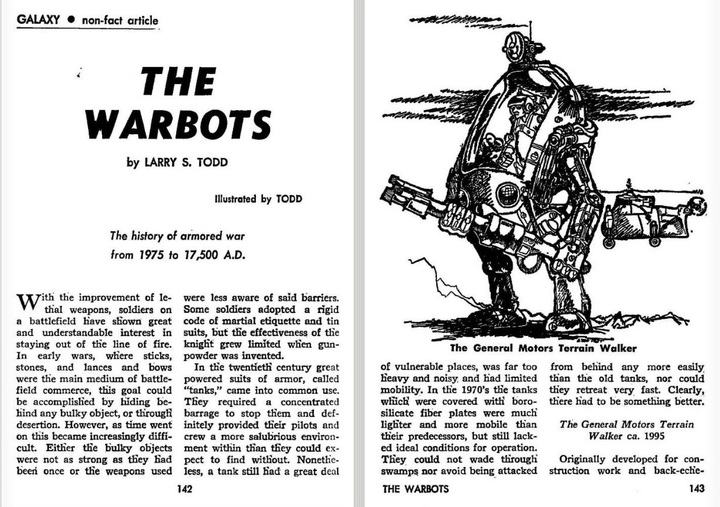

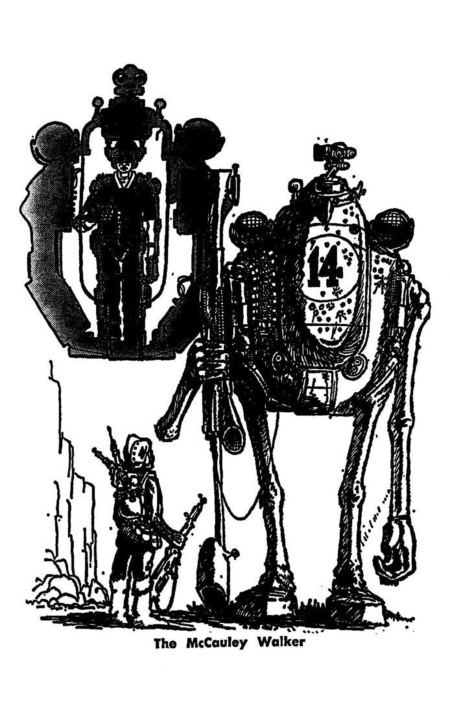

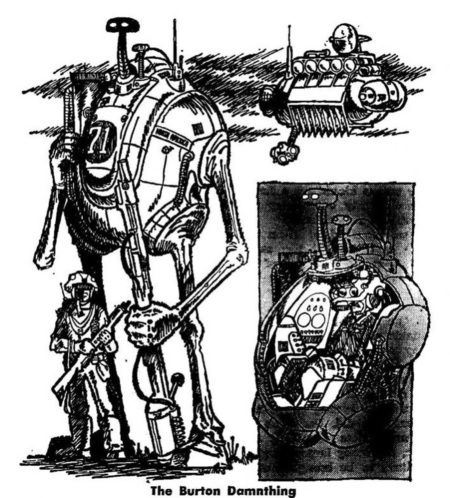

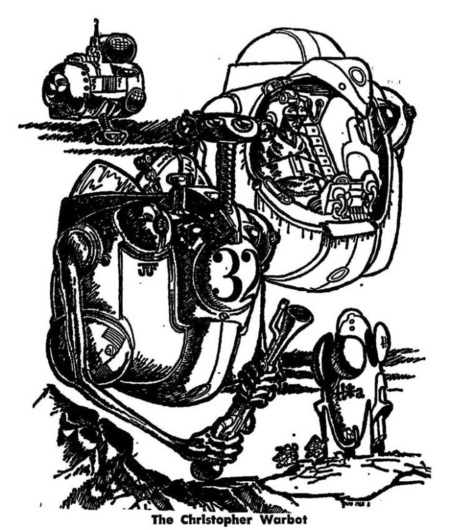

The features include Willy Ley’s long-running science column, “For Your Information,” discussing Explorer-1. Fred Pohl contributes an editorial, discussing the upcoming Presidential election (the one in which Nixon beat Humphrey and Wallace), and speculating about computerized voting from one’s home (even on laws, declaration of war, etc. — i.e. direct democracy). There is a Bio feature, Galaxy’s Stars, giving tidbits about a few of the authors. One piece, “The Warbots,” by Larry S. Todd, is designated a “Non-Fact Article,” and it discusses the history of tanks, basically, far into the future.

[Click the images to embiggen.]

Warbots art by Todd

[See detailed reproductions of the early mech artwork from “The Warbots” at 2 Warps to Neptune.]

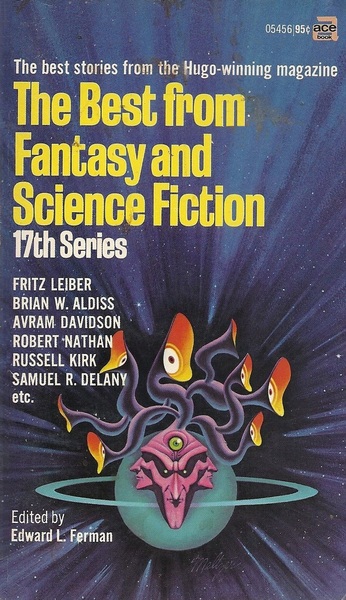

And then there’s the book review column, Galaxy Bookshelf, by Algis Budrys. It begins with a couple of diatribes. The first is against Little, Brown and Company, which have sent him (actually sent Ed Ferman, misaddressed to Galaxy) a review copy of a book for children, Marooned in Orbit, which Budrys finds awful, scientifically absurd, and thus contemptuous of SF readers of whatever age. The second is addressed to writers who self-publish – he warns them he won’t review their books.

|

|

Then he comes to The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, Seventeenth Series. His review is very well worth reading, though you might argue with him. He praises F&SF in general for the standards of prose maintained there, but he says “here’s evidence of an intelligent, organized, persistent, honorable and yet different description of science fiction.” He goes on to contrast the stories written by SF regulars (Davidson, Delany, Leiber, Aldiss, and Goulart) with some written by outsiders (Monica Sterba, George Collyn, Victor Contoski, Russell Kirk, and Robert Nathan). His main bone to pick with the non-SF writers is that they don’t know the genre:

They tend to have bright ideas without knowing those ideas have ever been touched on before, but they have: they have, down in the depths where the hacks ply unread.

He also says:

The essential thing that sets Russell Kirk and Robert Nathan apart from Robert Bloch and Arthur C. Clarke is that the latter study the former, whereas the former study their educations.

And finally,

One kind of story is by people who are engaged with life and use facts to grapple with it… Another kind of story is by people who are engaged in some form of professional contemplation… Those people tend to grapple with words and other symbols not as tools but as things in themselves.

He goes on to cite Thomas Disch’s “Problems of Creativeness” as a story that “touches rather effectively on this whole business.” (Alas, he doesn’t much like the Disch story on the whole.)

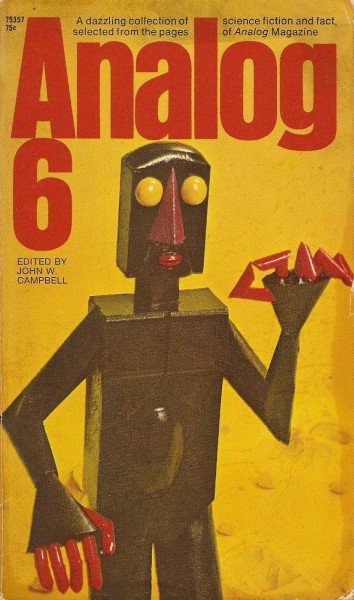

Budrys then considers the latest “best of Analog,” Analog 6; and comes to the predictable conclusion that Analog’s definition of SF is rather different than F&SF’s, without really suggesting that either magazine is the better. He has praise for “Light of Other Days” and “Call Him Lord,” and, in a different way, Alexander Malec’s “10:01 AM, but isn’t too impressed with Vernor Vinge’s “Bookworm, Run.” The column ends on a (purposeful, I am sure) vague note.

Okay, then, what about the stories.

Novelettes:

“The Villains from Vega IV,” by H. L. Gold and E. J. Gold (7,800 words)

“Thyre Planet,” by Kris Neville (8,500 words)

“Criminal in Utopia,” by Mack Reynolds (6,900 words)

“I Bring You Hands,” by Colin Kapp (7,700 words)

“Behind the Sandrat Hoax,” by Christopher Anvil (7,900 words)

Short Stories:

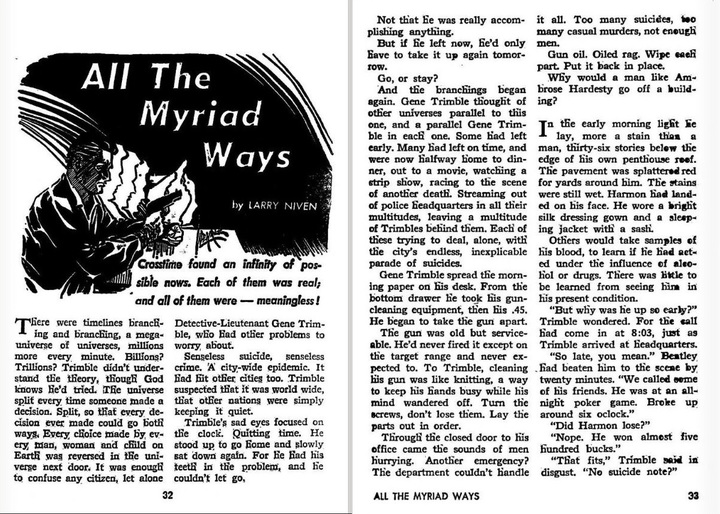

“All the Myriad Ways,” by Larry Niven (3,500 words)

“Homespinner,” by Jack Wodhams (2,000 words)

“A Visit to Cleveland General,” by Sydney Van Scyoc (6,100 words)

All the novelettes, I note, are of similar and fairly short length. And all the writers are fairly well-known (some perhaps less so today!) — no “LKWs” this issue. I’ll assume I need to say little about most of them… Sydney Van Scyoc (b. 1939) is one interesting case, a writer who never became quite the thing, but did some interesting work. She wrote 11 novels and perhaps 30 short stories, from 1962 to 1991, with a couple of late stories in 2004 and 2005. Jack Wodhams (b. 1931 in England, but in Australia since 1955) is perhaps the least known of these writers, but he used to show up regularly in late-Campbell Analogs. After Campbell’s death he seems to have all but abandoned the US market, but published quite a few more short stories and his only three novels in Australia over the next 15 years or so.

The cover story, “The Villains from Vega IV,” by Galaxy’s founding editor and his son (who much later became Galaxy’s last editor), is a comic story about an android cop who is assigned to help the visiting President of Vega IV, an outworld colony. Much is made of Outworld habits — the Bird of Perdition they carry that recites their crimes (labor is too important on Outworlds to punish crimes by imprisonment), the habit of making anyone who just got married President so they enjoy diplomatic immunity on their honeymoon trip, etc. The plot turns on the President’s quest to reclaim his bride, who has run away to be an actress; and on the marriage habits of Vegans. It’s all a bit silly, but it’s funny enough, and manages to not quite outstay its welcome.

“Thyre Planet” art by Adkins

Kris Neville’s “Thyre Planet” is a bit more serious, if not entirely so. The story has two foci, and I’m not sure they work together. On the one hand it’s a fairly broad satire of the executive personality, almost Dilbertian in spots, as Mr. Bellflower, a very well-trained expert executive, is hired by Thyre planet to solve the reliability problem with their transport booths, which were left by the natives of Thyre, who have all disappeared. So Bellflower’s strategies are shown, which prove to be more based on establishing a power base and keeping the money flowing than on actually solving the problem. Thus, a solution to the problem is the worst thing that could happen — despite the fact that thousands of people a year are lost in the transport booths. The other focus is of course the problem — and its solution, which is fairly clever, if, I think easily guessable. I liked both aspects of the story, but they seem to sit a little uneasily together.

“Criminal in Utopia” art by Brand

“Criminal in Utopia,” by Mack Reynolds, features a man in a “perfect” future, certainly one with excellent surveillance and hard to hack electronic money, who lives a fairly limited life, and needs to steal from someone to get the luxuries he wants. He manages to do so via a (not entirely convincing) scheme… leading to the expected mild twist. Not great stuff, but competent enough.

“I Bring You Hands,” art by Virgil Finlay

Colin Kapp’s “I Bring You Hands” is about a man who has invented mechanical hands that can be trained to do repetitive work, and do it much better than people. He is shown making a sale to an unscrupulous factory owner, who mistreats his employees. The hand seller hires one of the workers to train the hands to do her job — and he takes her as his mistress as well, to his wife’s displeasure. I had guessed from the beginning (having seen this trope in more than one horror story!) where this was going, and I’m sure you can as well.

Christopher Anvil (real name Harry Crosby) was an Analog regular (I think of him as John Campbell’s “Eric Frank Russell replacement”), and “Behind the Sandrat Hoax” really does look like a story aimed at Campbell. There is a persistent rumor that eating a sandrat on Mars will allow one to survive if marooned without water in the Martian desert, and when a man does survive in impossible circumstances, there is an investigation into how he might have survived. But the scientific authorities can’t believe in the silly “sandrat” notion — the man is sent to an asylum, while the scientist who dares to give some credence to the notion that eating a sandrat could help one get water in a desert has his career ruined, as a series of letters reveal the bureaucrats suppressing evidence, etc. A bit over-obvious, with over the top villains.

The one truly famous piece in this issue is Larry Niven’s “All the Myriad Ways,” in which a policeman puzzled by the recent wave of suicides ties them to the recent realization that there are infinite parallel worlds in which we each make slightly different decisions. The implication is that any decision we ourselves make is meaningless — because “we” will make every possible different decision anyway, in another world. So, why not commit suicide? I remember being really blown away the first time I read the story, but somehow it doesn’t have the same impact any more, and somehow the logic that seemed inevitable on the first reading doesn’t convince me now.

Australian writer Jack Wodhams’ “Homespinner” is about homes that can be reconfigured easily to a completely different arrangement. A man gets frustrated that his wife is never satisfied, and is always rearranging their home, never letting him get used to things. The twist ending actually works, partly because the story is short enough to be contained mostly in its twist.

And Sydney Van Scyoc (no middle initial “J” this time) gives us a story about a future in which much medicine is handled by automation. Doctors and nurses have a different function, which slowly comes clear as reporter Albin Johns, on his first day replacing a veteran, comes to Cleveland General for a tour. Albin has memory problems, and the visit confuses him — he’s never been to Cleveland General, so why is it familiar? He learns some curious things — a woman who is given a sterilization treatment without consent, and told that her baby has died, while another woman is surprised to receive a healthy child… and Albin starts to remember strange things, like his scars, and his superstar brother Deon, and… Well, you can probably see where this is going. I think there’s a pretty decent story here, potentially, that van Scyoc doesn’t quite pull off.

Several of these stories – a surprisingly high percentage – have twist endings, and I have had complaints that I am too coy about revealing endings. But other readers complain about spoilers. So, after some early mech artwork by Todd illustrating “The Warbots,” here’s the twists for those stories.

“Thyre Planet” The problem with the transportation system is a simple computer bug, made by the alien natives of Thyre, such that every so often the transportation booths don’t rematerialize people at their destination. But all the data or whatever that holds the transported stuff remains in the memory banks. When the humans solve the problem and fix it (to the discomfiture of the executive who wanted to keep his position as leader of the effort to “solve” it), all the missing humans — plus, more importantly, all the mysteriously vanished natives of Thyre — suddenly show up at their original destinations.

“Criminal in Utopia” The criminal turns about to be employed by the state to test their methods of crime prevention, showing up vulnerabilities.

“I Bring You Hands” The scorned wife, disgusted at her husband’s affair, programs a set of his hands to strangle him, and leaves them ready to be activated when he finally comes home. (How many horror stories are there about disembodied hands strangling people?)

“Homespinner” The husband, frustrated with his wife’s constant “respinning” of their home, deactivates her and gets ready to spin himself a better model of wife.

“A Visit to Cleveland General” Albin and his brother Deon were in a terrible accident, and Cleveland General saved them by knitting together bits and pieces of both Albin and Deon to make one functional person, but the memory pills Albin takes are actually forgetting pills, so he will not remember the traumatic accident, nor his combined identity… there’s a hint, as well, that the reporter he’s taking over for is ill and will be euthanized.

[Read the complete text of this issue of Galaxy online here.]

Rich Horton’s last article for us was Hugo Nomination Thoughts, 2017. His website is Strange at Ecbatan

I have a copy of Benchmarks: Galaxy Bookshelf, which collects Budrys’ reviews for the magazine from 1965 through 1971. It’s well worth hunting up. He was always sure to say something sharp and thought provoking, even if you don’t always agree with him.

If I have a copy, I’ll check to see if mine has staples. I don’t have as many of the later issues, though.

Thanks.

Fun to see Gaughan imitating book in the first illustration for “The Villains,” and inveterate swipe-artist Adkins borrowing a Steranko right hand for the figure on the left in the “Thyre Planet” illo.

Imitating BOK — Hannes Bok — was what I meant. Sorry.

I don’t have that issue, but my September 1968 is the same way, but my staples look a bit cleaner. But if you open up the early ones from the ’50s and look at the back page, you should see a couple of staples there, too. They just do a better job of hiding them. But the ones from the ’50s have only two staples; the larger issues have three. And then they probably glued the cover to the spine.