The Poison Apple: Have Long Sword Will Battle, An Interview with Martin Page

Martin Page demonstrating German Longsword at Compulsion

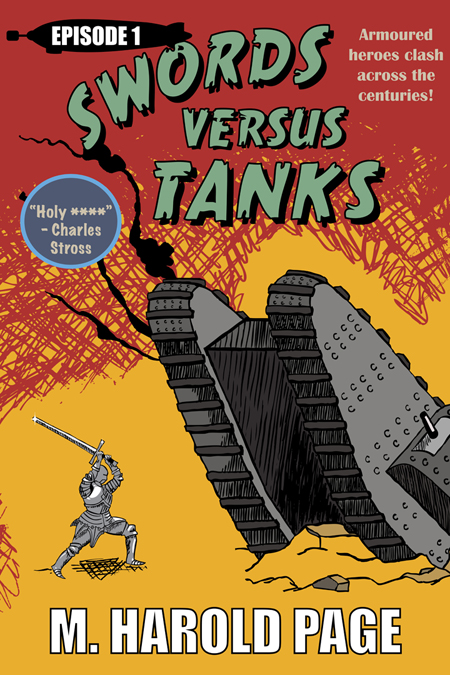

Martin Page is a regular contributor to Black Gate and writes novels, such as the alternate history mash-up Swords versus Tanks and non-fiction books like Storyteller Tools, under the pen name, M. Harold Page. He lives in Edinburgh, Scotland and teaches Medieval German longsword at Edinburgh’s Dawn Duellists Society.

Martin, what have you been working on?

I’ve been taken a break from blogging while working on a space opera series. I’ll shortly return with a series of articles on the new edition of Traveller, the famously gritty Science Fiction roleplaying game.

Traveller?

Massively influential game from the same era as Dungeons and Dragons but still going strong. Traveller has been around so long at this point that people recommend books or TV series that are strangely like the game, because they were probably heavily influenced by it!

I started playing it at the age of thirteen, and now my thirteen-year-old son is actually refereeing it and all the kids in the neighborhood want to play. So it’s come full circle like a Country and Western song! I’ll probably also guest on Charles Stross’s blog about this, but from a different angle.

Weren’t you and your kids also involved with re-enactment?

I haven’t done that for a long while! I am however deeply involved with HEMA or Historical European Martial Arts at Edinburgh’s Dawn Duellists Society.

My son has joined me on some HEMA events, and my nine-year-old daughter has expressed interest in bashing people with swords, as well, but for the most part the children are involved with tabletop war-gaming rather than HEMA.

Martin Page. Photo by Elizabeth Crowens

How did you get involved with HEMA?

Edinburgh is tiny, and everyone knows each other in these slightly Bohemian/Goth/Geek/Alt/Nerd circles. Paul Macdonald is one of the founders of HEMA in the UK and is also a sword smith (macdonaldarms.com/armoury). A curator friend needed a replica Viking sword so I took him to Paul’s workshop. There were all these weapons from the sorts of books I had read! Every time I picked one up, Paul would pause in negotiations with my friend and show me how to hold it! Then I thought to myself, “Good God! This is awesome.” I still thought these guys were nuts, but I wanted to write about people who fought with swords. Then I figured I’d have a go with it for about a year, and that’ll be the end of it, but that was twenty years ago or so. I have a sword scar — a training injury. Don’t parry with your hands. That’s when I traveled down to England did battle re-enactments. Fighting in plate armor is great. I used to love that.

If I was younger and had more money I’d be involved with the Battle of Nations. Those people are absolute lunatics, and they pound the bejesus out of each other like a medieval tournament. (Real battles were actually nastier. You’re not hitting the armor. You’re trying to ram the point of your sword in the cuff, the chin, in the eyeball, in the ‘nads — that’s what the advice in the manuals is. Basically you are using your sword as a crowbar and a knife, and you get to fight in full armor.)

What I teach is German Longsword, which is unarmored. It’s worn more like a civilian sidearm – say a Colt 45. You don’t want to use it as your primary weapon if a thousand men in plate armor surround you.

Longsword is great fun. I get to train and fight once a week, and we go to the pub afterwards. Basically, I got involved with HEMA to write about sword fighting. It was also a way to stay fit and a way to meet others that are interested in this sport. My writing is obviously influenced by it to a certain extent although I’ve never been in a real fight with sharp weapons, and I’ve never been shot at, but at least I have some reference points to work with.

Teaching German Longsword. Photo by Elizabeth Crowens

Martin, when I first met you I was invited to your class on German Longsword. Do you train in any other style?

My club does. We have sword and buckler, which is the earliest documented weapon. That goes back to about 1300 A.D. We also teach 19th century military saber, and other times we have manuals available if people want to gather together and practice other weapons such as the spear, and the poleaxe, which is quite dangerous, because it is designed to break plate armor, and plate armor tends to wreck the inside of buildings…

This leads to my next question as to where most people train and practice using these weapons?

Don’t train in your house with this stuff, or you’ll leave gouges in your walls. I think the Battle of Nations trains in a large gym with mats.

You’ve never suited up in armor and fought on a horse?

That’s an agreement I have with my wife. No horses. That’s why I like writing in the Dark Ages and the 15th century, because those are the two eras that you can be a fighting man and not spend all that much time fighting on horseback. A lot of the classic battles back then were fought on foot. Horses are very large targets for men with arrows.

That is true, and I’m sure it’s not too fun to fall off a horse. Okay, now I know you have a background in history. Let’s talk a little bit about the fighting, along with your educational background and how you ended up writing about it.

I started off with trying for an engineering degree, because I like science fiction, but I was a complete disaster. So I switched majors and went for Classics and Medieval History — Fall of Troy to the Fall of Constantinople! I did a postgraduate degree as well researching Anglo-Scottish Border warfare. (Rah!)

I was always obsessed by medieval stuff and would’ve done the sword fighting regardless. My knowledge of history has helped me make more sense out of the old fight manuals with illustrations we use for reference and also helps with the context. Straight translations of these can be quite cryptic — they assume you already know how to do this stuff! It’s a bit like playing Twister with old manuscripts and swords.

The 18th and 19th century fight techniques are usually bettered written up. In the 19th century you get more how-to-books basically, How to Kill Someone with a Saber, or books similar to the martial arts manuals you see in stores today.

Photo by Elizabeth Crowens

Do you think the older stuff was written as if it were expected that one was to go through an apprenticeship, and it was more of an oral, handed down tradition anyway?

Just about the only medieval martial arts manuals come from Germany and Northern Italy. To have owned one of these manuals showed others that you were literate and interested, but the bottom line was that these people would have attended actual classes. There were guilds of actual fencing masters. Having this manual would be like getting the crib notes for an exam. Maybe its purpose was just to refresh one’s memory of those lessons or just to prove after the fact that you’ve taken these classes.

Now I’m going to talk about your book on the craft of writing, Storyteller Tools: Outline from Vision to Finished Novel Without Losing the Magic. (mybook.to/StoryTellerTools) I’m assuming you must be an outliner. Is this correct?

I started out as a Panster with Swords versus Tanks and realized I couldn’t do it. There was too much to keep track of. I discovered in the end that the best way of outlining was to do it as if you were telling a story in the first place. One time I got into a mess where I had two different plotlines with incompatible conclusions, and I couldn’t finish the damned novel. It was a bloody logjam.

You obviously get into so much world building with Swords versus Tanks.

These days I tend to build the world as I build the plot. In my space opera, I had to build the world first, because I want a particular flavor. Then I had to plot within it.

What authors or books both modern and history have been influential to your writing career?

Thomas Mallory. As far as people were concerned, Mallory was a real knight and knew what it was like to fight in armor. Others would be Beowulf and Homer from the distant past. For modern — Robert E. Howard, David Gemmell, historical authors Harold Lamb and Ronald Welch, and Leigh Brackett. She is now best known for the film scripts of The Big Sleep and The Empire Strikes Back. However, she was a wild pulpster before that, with a dark edge.

Do you do a lot of research when you write your historical fantasy?

A lifetime’s worth! As for my approach – read the Black Gate article I wrote on this: I layer it and tend to think of it in military terms all the way from strategic to tactical.

It’s very easy to get it wrong. For example, people assume that merchant caravans would have mercenary guards while crossing Europe. However, in medieval Europe you couldn’t cross someone’s land with armed guards. You’d be brought to battle, and that would be the end of you. Basically, what you would do is that every time you changed the local lord would say, “Welcome to my territory. My men will escort you across. It will only cost you so much.” You’d also be expected to change guards every time you cross into someone else’s land. So, you need to know how stuff works, but not get lost in details.

In preparing for this interview I want to let you know that I read Swords versus Tanks.

Ah, my magnum opus.

What made you decide to combine a modern universe with tanks and technology with a more archaic one?

The idea of knights facing off against tanks with magic just struck me as the type of thing you put on a 1980’s heavy metal album cover. I wanted to do something nuts, and I think I did. It was my first big novel.

Another thing was that I was very interested in modernity versus medievalism. I liked the individualism and psychological healthiness of the way that knights thought like, “I won the battle therefore God was on my side… I killed some people, but that’s all right… I’ve done my penance suffering in the fields wearing all this bloody armor. Now I can go home to my family.”

A good example: King James IV of Scotland was the quintessential patron of the arts, literature and science during the Renaissance, but he died with a sword in his hand at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. Sometimes the nobility had a go at it just like mad barbarians.

There was also a moral pit fight going on in my book at the same time of banging these two technologies together: Collectivism (paternalistic) versus individualism (strong moral ethics), as well as modernity versus psycho heretic burning and murderous homophobia. I think I was influenced partly by Tiananmen Square and that incident where there was that incredibly brave chap on a bike who stopped an entire line of tanks by sheer force of personality. Now, what if he had a magic sword?

Photo by Elizabeth Crowens

As you were describing this it reminded me of might versus right — an honor concept with the medievalists, and yet with the technology of their enemies it’s like, “I’ve got bigger guns than you have, and they shoot faster and harder, or I’ve got a bomb in my pocket, and you’ve just got a sword.”

Yes, and we saw where that went. My favorite bits in that novel are when I got to mix the technologies up and have the invaders face absolute disaster. At one point I have this marvelously incompetent commander that refuses to believe in all this magic rubbish with amusing results. The magic the natives have is imported from a Viking-like culture. Their swords cut through metal quite easily, because the swords are enchanted, but that doesn’t affect wood. So the invaders do adapt and take steps like covering their tanks in wood.

But magic becomes more important as the storyline goes on. There is an arms race. The medievals are trying to rediscover magic to fight off these invaders.

And there are Vikings on zeppelins using Tommy guns.

Martin Page with Elizabeth Crowens having

lattes at the Elephant House, where

J.K. Rowling wrote Harry Potter

Readers can find more about Martin Page by checking out his posts on Black Gate or at his website mharoldpage.com.

Elizabeth Crowens is a Hollywood veteran, journalist and author of Silent Meridian, an X Files for the 19th century steampunk novel series, finalist for the 2016 Cygnus Awards in Speculative Fiction, the Goethe Award in post-1750’s Historical Fiction, Paranormal and Ozma Fantasy Awards. www.elizabethcrowens.com, Facebook: @BooksbyElizabethCrowens, Twitter: @ECrowens

Glad to see a fellow HEMA enthusiast here at Blackgate!