Reading for the End of the World

|

|

Back in 1977, near the high water mark of an earlier age of apocalyptic expectations, Elvis Costello crooned a song about “Waiting for the End of the World.” It seemed to make sense in that era of turmoil and unrest at home and abroad, but the American landscape of the last year or so makes the turbulent 70’s seem like an age of cool, good humored rationality. (It wasn’t — trust me.)

I, along with Little Orphan Annie and MacBeth, still expect the sun to come up tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, but even so, it does indeed feel as if we have arrived at the end of something, and business as usual just won’t do anymore; adjustments are called for in many aspects of our lives, including (of course!) reading. Extraordinary times call for extraordinary literary measures. Therefore… to the barricades — uh, bookstores!

In the spirit of the incipient panic, withered expectations, and rampant paranoia that seem to dominate our current national life, I offer twelve books to get you through the next four years (however long they may actually last): a reading list for the New Normal.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

|

- The Manchurian Candidate by Richard Condon, 1959

The winner and still heavyweight champion of all American political thrillers, due to the audacity of its concept and the ruthlessness of its execution. What if a presidential candidate were actually the instrument of a hostile foreign power? What if said candidate was backed by a clandestine network of agents ready to manipulate a vulnerable system and dupe a gullible public in order to place their man in the White House, from which elevated position he would then place his country’s neck firmly under the collective boot of his hidden masters? What an absurd fiction – or what a brilliant idea, depending on who you believe. The 1962 film, directed by John Frankenheimer and starring Frank Sinatra, Laurence Harvey, and Angela Lansbury, is very faithful to the book, except in one regard – downbeat as the movie’s ending is, it’s all sunshine and roses compared to the desolate, utterly bleak, midnight black conclusion Condon gave his novel. And no, I’m not going to tell you what it is. Find a copy and read it – it will amply reward your time, even if you know the film forwards and backwards. Condon’s mix of apocalyptic political intrigue, suspense, incest, and existential tragedy is brilliantly unique and original; served up with a skeleton-grin cynicism and with a chill wind blowing through its soul, there’s still nothing quite like it.

|

|

- Night of Camp David by Fletcher Knebel, 1965

Senator Jim MacVeagh is unexpectedly invited up to Camp David, where the President has a long private chat with him, telling the idealistic young Iowa legislator that he has chosen him to be his running mate for the upcoming election. During their long confidential talk, Jim begins to suspect that something is not quite right with President Hollenbach, and in observing the man closely over the next several days, Jim comes to the conclusion that the leader of the free world is, in fact, dangerously insane. But how can Jim get anyone to believe him – and even if he can persuade anyone to accept his version of events, what can they do about it? (At the time the book was written, the twenty-fifth amendment – about which you’ve doubtless heard more in the last few weeks than you have during all the previous days of your life put together – had not yet been ratified.) The book is very much a product of its time but is still a solid political thriller; Knebel knew how the system worked, having spent almost thirty years braving the District’s atrocious climate (meteorological and moral) as a Washington correspondent.

|

|

- It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis, 1935

A full-blown depiction of an America in the grip of a fascist regime, It Can’t Happen Here periodically comes back into vogue whenever events seem to warrant it. Not surprisingly, it had its last big surge during the Nixon administration. Lewis imagines a populist demagogue named Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip — very much in the mold of Louisiana Senator Huey P. Long — defeating FDR with a combination of folksy blarney and outrageous economic promises, and then rapidly gaining a stranglehold on power by using his own home-grown Brownshirts (called the Minute Men) to suppress dissent and intimidate opponents. All the standard fascist trappings soon appear in the Home of the Free — a populace bamboozled and bludgeoned by perpetual propaganda (facilitated by a completely tamed media), an emasculated legislature, concentration camps packed with dissidents, persecuted minorities used as scapegoats, inoffensive foreign nations invaded (the better to distract citizens from the fact that Windrip’s economic promises have come a cropper), and ultimately a burgeoning underground resistance movement that eventually erupts into a second civil war. The book ends with the issue still in doubt, but with Lewis affirming the values that deserve to triumph — decency, tolerance, integrity, humor, and allegiance to the plain truth.

|

- The Plot Against America by Philip Roth, 2004.

In a vein similar to It Can’t Happen Here, Roth postulates a world in which Roosevelt is defeated for reelection, but in 1940 instead of 1936, and not by a populist blowhard; FDR’s opponent here is the stoic and enigmatic Great American Hero himself, isolationist aviator Charles A. Lindbergh. War versus peace is the key issue in the campaign — Lindbergh’s slogan is “Vote for Lindbergh or vote for war.” A public made nervous by FDR’s aid to Great Britain sweeps Lindbergh into office, and the Lone Eagle’s administration quickly becomes a hotbed of German sympathizers and unashamed anti-semites. Steadily escalating persecution of Jews and other minorities follows, and after the assassination of a vocal administration opponent, the broadcaster and columnist Walter Winchell, the country descends into violence and chaos. Lindbergh finally abdicates by flying away, never to be seen again, Roosevelt is returned to power in a special election, and the country awakens as from an evil dream. The Plot Against America, which I reviewed at greater length here, is a genuine alternate history, as convincing and frightening as any in the genre.

|

|

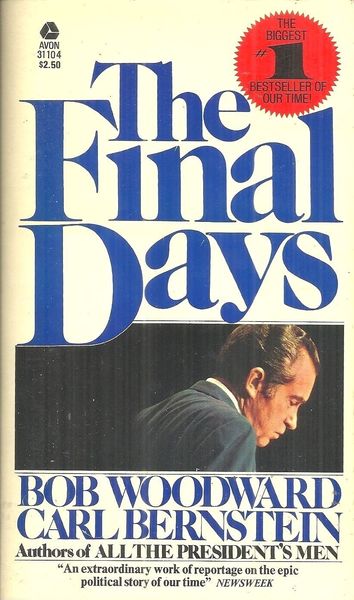

- The Final Days by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, 1976

Truth is stranger than fiction, or so they say, and they were probably thinking about The Final Days when they said it. An account of the last few weeks of the embattled Nixon administration, its portrait of one of the most rigidly controlled men in American history coming unraveled under the enormous pressure of impending impeachment is riveting and deeply unnerving. In intimate detail (based on hundreds of interviews), we see the most powerful man in the world simply cracking up: talking to the portraits of his predecessors as he wanders sleepless through the White House; swinging uncontrollably between maudlin self-pity, stoic resignation, and cornered-animal combativeness; alternately weeping while praying and praying while weeping; and drinking, drinking, drinking, all while those around him try to figure out how to maneuver him into just going quietly without deepening the already enormous domestic crisis or precipitating a dangerous international situation. Absolutely harrowing, perhaps even more so now than when it was written.

|

|

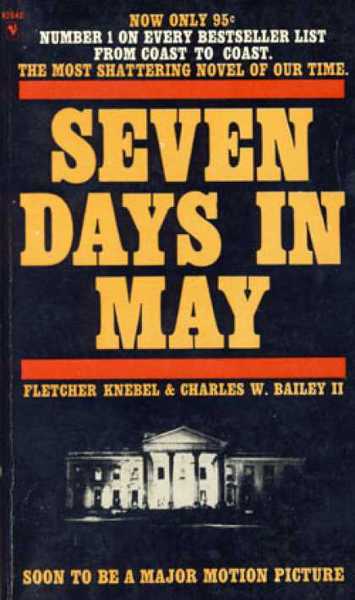

- Seven Days in May by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey, 1962

In a earlier run-through of Night of Camp David, a Pentagon Colonel who works for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff inadvertently stumbles upon evidence of a military plot to overthrow the government, a plot that is already in motion and that will reach fruition in just seven days. (The chiefs — and much of the country — are opposed to President Jordan Lyman’s pride and joy: a treaty that is about to be entered into with the Soviet Union that will require both nations to completely dismantle their nuclear arsenals. Only a suicidal idealist would trust those shifty commies.) Once again, the big question is simple: who can Colonel Casey get to believe him, given his skimpy and ambiguous evidence? Even the President is initially skeptical. Once he’s convinced though, it’s a nail-biting race against the clock as Lyman and his loyalists try to get the upper hand. Ably filmed in 1964 (again by John Frankenheimer), with Kirk Douglas as Colonel Casey, Fredric March as President Lyman, and in a chilling performance, Burt Lancaster as the egomaniacal would-be Caesar, General James Matoon Scott. Both book and movie have a wild twist: in his fight to foil the coup, you’re rooting for the President.

|

|

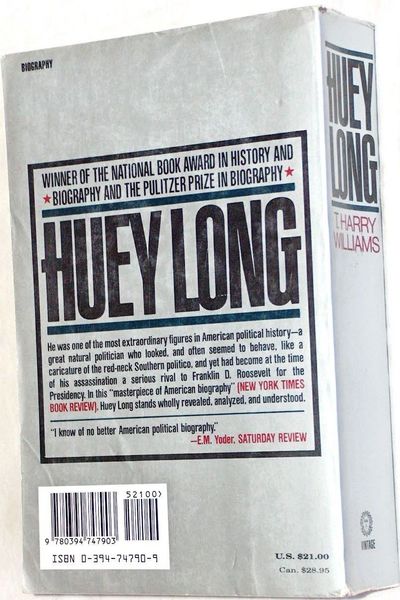

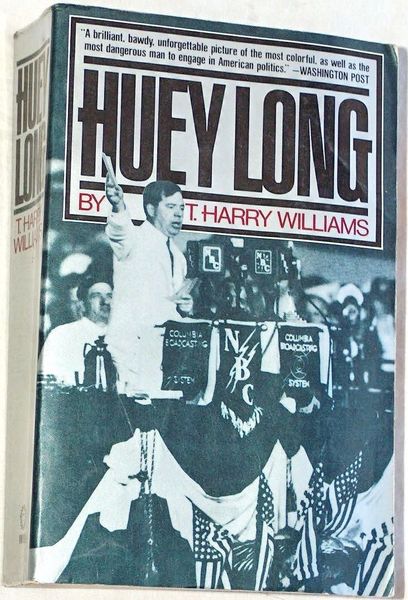

- Huey Long by T. Harry Williams, 1969

The governor and later senator from Louisiana is often cited as the man who had the best chance of bringing fascism to America, and with good reason. A politician of genius, Huey Long established a dominance over his state that was as close to absolute as has ever been seen in this country. His aim was never to merely defeat his opposition; he wanted to destroy it so thoroughly that, in practical terms, it would completely cease to exist. In this, Long succeeded to an extraordinary degree. He pushed a corner-cutting economic and social populism that brought some genuine benefits to his wretchedly poor state, while it also ran roughshod over the political rights of anyone opposed, in whatever degree, to the aims or methods of the Kingfish. A Democrat, Long had his sights set on wresting the presidential nomination from Franklin Roosevelt in 1936 (and many people thought that FDR was vulnerable to the kind of challenge Huey would mount, especially in a country still deeply mired in the miseries of the depression) and was building a nationwide organization (anchored by “Every Man a King” clubs) when he was shot by an assassin in the Baton Rouge statehouse on September 8, 1935. He died two days later. His last words were, “God, don’t let me die. I have so much to do.” Williams’s book is a great American biography, thorough, fair, admiring of the skill and drive (and even genuine concern for the poor) that Long had, and appalled at his coercive ruthlessness and corrupted ambition. After you read it, if you need more insight into the appeal that Huey’s kind of populism had — and still has — give a listen to Randy Newman’s superb 1974 album Good Old Boys, which he wrote after reading Williams’s book. Play “Rednecks,” “Mr. President (Have Pity on the Working Man),” “Louisiana 1927,” “Every Man a King,” (the official song of the organization and written by Huey himself), and “Kingfish.” They may help you understand how we wound up wherever this is that we are.

|

|

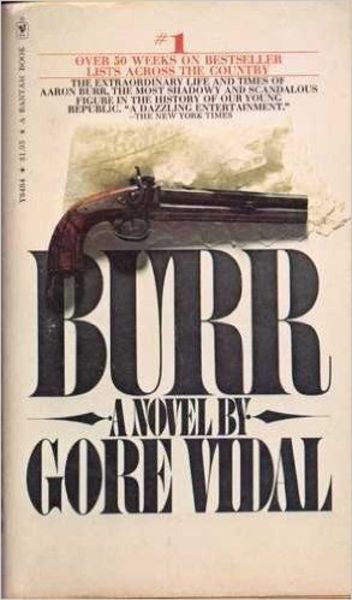

- Burr by Gore Vidal, 1973

Once upon a time, an unscrupulous and unprincipled opportunist came within a hair of winning the presidency. (“Missed it by that much!” as Maxwell Smart used to say; one electoral vote, to be exact.) No one knows how differently our history would have developed had Aaron Burr become the third President of the United States of America in 1800 instead of Thomas Jefferson, and Vidal’s novel doesn’t concern itself with that question. It is instead a retrospective of Burr’s career largely told by the man himself in his old age, and is a biting commentary on the unedifying way politics actually works. The great early American villain (along with Benedict Arnold) of countless excruciatingly dull high school history texts is, in Vidal’s acerbic and epigrammatic hands, a witty and constantly entertaining narrator; his acid-etched portraits of his great contemporaries (Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and of course, Hamilton) are unfailingly unfair and just as unfailingly delightful. (In an afterword, Vidal cautions readers against confusing Burr’s opinions with his own.) Vidal’s Burr is undeniably a scoundrel, but he isn’t a hypocrite, which makes him the possessor of one signal virtue at least. So let’s cut him some slack; if he wasn’t a hero of history let’s permit him to be the hero of this fine novel — it’s a cinch no one will ever write a musical about him.

|

- An American Melodrama: The Presidential Campaign of 1968 by Lewis Chester, Godfrey Hodgson, and Bruce Page, 1969

Only old folks actually remember this, but once, and not really all that long ago, the political and social situation in these United States was so bad that many people thought that the country was completely falling apart, and that it may even have been headed for civil war. 1968 (the “hard year” in the words of failed anti-war Democratic candidate Eugene McCarthy) saw urban riots, escalating disaster in Viet Nam and increasingly violent resistance to that war in the streets of America’s cities, mounting conflict between diverging polities (sexual, racial, economic, generational), and of course, two assassinations of major political figures – Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. The year culminated with the chaotic Democratic convention in Chicago that put “police riot” in the American vocabulary and that resulted in the nomination of a compromised and crippled Hubert Humphrey, who then lost the election to Richard Nixon. There have been many accounts of that grim and pivotal year, but this book by three British reporters is still one of the best. Their foreignness gave them a detachment and an objectivity that no American journalist could match (not in the boiling cauldron of 1968, anyway) and while judgments refined by time are of great value, An American Melodrama‘s immediacy is a real virtue; the pages still seem damp with blood and sweat, and warm with the heat of fires from looted and burning buildings. There is one thought that reading this book today may inspire that couldn’t have occurred to its first readers, however – we got through those hard years, even when it seemed the whole country was collapsing around our heads; in 1968 counsels of despair were the wrong ones to listen to. That’s always a good thing to remember, even — and especially — today.

|

|

- The Caine Mutiny by Herman Wouk, 1951

When Lieutenant Commander Phillip Francis Queeg takes command of the USS Caine, his crew is less than enthusiastic, as Queeg, a stickler for doing things “by the book,” tightens discipline on what was until his arrival a very relaxed ship. (Would it be too much to say that while Queeg always had a shaky hold on his men’s popular vote, the electoral vote of the Navy was decisively cast in his favor?) The obsessive-compulsive captain soon starts manifesting symptoms of paranoia and persecution mania to such an extent that he almost entirely loses the loyalty and confidence of his crew until, during an extremely hazardous typhoon, the ship’s executive officer Lieutenant Stephen Maryk forcibly relieves a dithering Queeg of command. Maryk’s authority is Section 184 of Navy Regulations, which says that a commander may be relieved by a subordinate in certain extraordinary circumstances, such as mental incapacity; it’s a sort of salt water 25th amendment, if you will. Once back in port, Maryk is put on trial for mutiny, along with Midshipman Willie Keith, who backed Maryk up at the crucial moment. A conservative man, Wouk was generally on the side of tradition and authority and thus keenly felt the danger that results when authority becomes aberrant or erratic, as he also was extremely sensitive to the pitfalls of dealing with — and even removing — such disordered authority. The book was memorably filmed in 1954, with Humphrey Bogart giving one of his finest performances as the mentally ill captain.

|

|

- The Dead Zone by Stephen King, 1979

The best of King’s “first phase” novels, The Dead Zone is the story of Johnny Smith, a young man who develops powers of precognition after emerging from a five year coma caused by an auto accident. Johnny’s visions generally come as a result of physical contact, and when he shakes the hand of up-and-coming politician Greg Stillson at an election rally, he has a searing vision of the future, a future in which Stillson is president. Does Johnny see Stillson signing housing legislation or greeting the nation’s top 4-H Club members? Of course not — he sees an eyeball-rolling crazy President Stillson initiating a nuclear holocaust. What should Johnny do? He could just not vote for Stillson, though that doesn’t seem quite enough, but on the other hand, he can’t quite work himself up to shooting the politician — not at first. He eventually does decide to take the leap into the ranks of Men Whose Middle Names Everybody Knows, but turns out to be a lousy shot. (I wonder why he didn’t know that beforehand?) It doesn’t matter though, because when Johnny tries to kill Stillson, the cowardly candidate grabs a child to use as a human shield — and everybody sees it. In 1979, that was enough to end a political career, believe it or not. How things have changed. David Cronenberg filmed the story in 1983 with an eerily perfect Christopher Walken as Johnny.

|

|

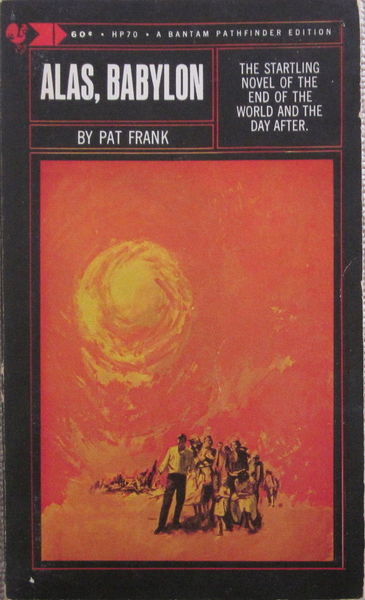

- Alas, Babylon by Pat Frank, 1959

C’mon – we’ve got to have one worst-case scenario here, don’t we? Alas, Babylon is one of the original post-nuclear holocaust novels, and all these years later it’s still one of the best. When everything goes up in fire and comes down in ash (what was the war about – does it even matter?) the residents of an isolated Florida town called Fort Repose escape more-or-less intact…except for that part about practically the whole rest of the world being incinerated, of course. The effects and aftereffects of a massive nuclear exchange are a good deal milder in the book than we now know they would be; nevertheless, Frank’s story is still gripping reading. Smoothly and involvingly written with credible characters and a suspenseful plot, Alas, Babylon is also full of helpful tips for foraging for food, sterilizing water, and stringing up looters, making it the last book you’ll want to burn for warmth if worse really does come to worst.

Of the twelve books I’ve listed here, only four are currently out of print: The Manchurian Candidate, Night of Camp David, Seven Days in May, and An American Melodrama. All are quite easy to find used, though, and I would bet that The Manchurian Candidate at least will be rushing back into print any minute now. (It is available as a e-book, but I think I’ll follow the wisdom of the people of Fort Repose and not rely on anything that could be flummoxed by an electromagnetic pulse.)

So there you have it: a dozen histories, actual and alternate, maps of action or aids to contemplation, to help you get through all the days of farce and folly that lay ahead, as we do our best to cope with the real history that we’re all trapped in.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Sure Cure for that Listless Feeling.

Great essay. You made me curious about all of these, some of which I’ve never heard of and all of which I’ve never read.

Plus, the phrase “I, along with Little Orphan Annie and MacBeth, still expect the sun to come up tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” may be the best damned thing I read all month. That, sir, was fine writing.

Always nice to have the Boss toss you a bone!

I second Howard’s sentiment about that sentence. Several of these books just climbed a few notches on my TBR list.

Weirdly, I’d say Hamilton is almost as much about Burr as it is about its hero. Burr gets to be the narrator for his rival’s life, and he has as interesting a developmental arc as any other character in the show.

I’ve been trying to think of books by women that would make sense on a list like this. I agree with the widespread sentiment that this is a good time to read or reread The Handmaid’s Tale, which I read three or four times in my teens and twenties, but I’m really curious now to check out her Oryx and Crake and its sequels, which are beyond dystopian into the post-apocalyptic.

If you don’t mind a little hope with your dystopia, Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed has the conflicting nations and cultures of Urras and Anarres, each with its excellences and each with its injustices, while our hero Shevek tries to avoid being used or constricted by either of them.

I haven’t read Mary Shelley’s The Last Man, but it would seem to fit the bill. The reviewers of the time thought its bleakness unladylike, but starting in the 1960’s it started to get more respect.

Do any others come to mind?

Sarah, the greatest work of history/political journalism that I’ve ever read is by a woman: Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, by Rebecca West. It’s not a book that a lot of people will be eager to jump into, though, as it’s 1,150 densely written pages about 1930’s Yugoslavia – a dark place in a very dark time. But the political, social, historical – just plain human – insight in the book is absolutely dazzling. It’s a project to read, to be sure (took me about six months) but every page is full of the kind of writing that’s so brilliant that you want to push people into corners and read it aloud to them.

I could also add just about anything by C.V. (Cicely Veronica) Wedgwood, especially her three volume history of the English Civil War: The King’s Peace, The King’s War, and A Coffin for King Charles. Barbara Tuchman’s The Proud Tower and The Guns of August would fit nicely too, though like Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, none of these books have American subjects, which doesn’t really matter – it’s just what instantly leapt into my mind when I was thinking of books, given our current situation.

For fiction, how about Angela Carter’s Heroes and Villains? I don’t know of a better post-apocalypse novel.

Those all look delicious, and they’re all new to me. I’ve read a lot of Angela Carter, but all of it short stories in which she’s making jazz with the old fairy tales. That novel looks both lush and bleak, which is an interesting balance.

I’ve had my eye on Black Lamb and Grey Falcon for a long time. You’re not the only person I’ve seen praise it that highly.

I’ve only seen the Caine Mutiny movie. I have mixed feelings about it. I saw Queeg as falling apart under pressure and attempting to find a scapegoat for his own pathetic leadership. I’ve seen this in the military but it didn’t have a nice ending like the movie. I like the end where the XO was told off by his peers for his lack of loyalty but I also felt the rage of how an incompetent man was propped up and backed by the high command. The fix was in.

I prefer the “Left For Dead” book which details the sinking of the USS Indianapolis. There, Captain McVay was sacrificed by the high command to cover their own incompetence but it actually happened. The cover up was complete and done if a 15 year old boy hadn’t been curious when he watched the movie Jaws when Hooper and the Captain were showing off their scars and tattoos. The darkest deed of the Navy was fully exposed and it was all a true story.

I just stumbled on your blog and this old post. The reading list seems appropriate for 2025.

I thought so too, so in February I posted Reading for the End of the World Redux, with twelve “new” books for 2025. Check it out.