The Valley of Gwangi Finally Reaches Blu-ray Because I Mistakenly Said It Never Would

During my years of writing for Black Gate, I’ve repeatedly pointed out certain films aren’t available on Blu-ray or DVD … only to discover after I post the article that said films are already scheduled for a release. This happened again three weeks ago when I mentioned that the only Ray Harryhausen film still unreleased on the Hi-Def format was The Valley of Gwangi. I dug myself in deeper by predicting we wouldn’t see one for years because of how slowly Warner Bros. moves with its catalogue titles.

During my years of writing for Black Gate, I’ve repeatedly pointed out certain films aren’t available on Blu-ray or DVD … only to discover after I post the article that said films are already scheduled for a release. This happened again three weeks ago when I mentioned that the only Ray Harryhausen film still unreleased on the Hi-Def format was The Valley of Gwangi. I dug myself in deeper by predicting we wouldn’t see one for years because of how slowly Warner Bros. moves with its catalogue titles.

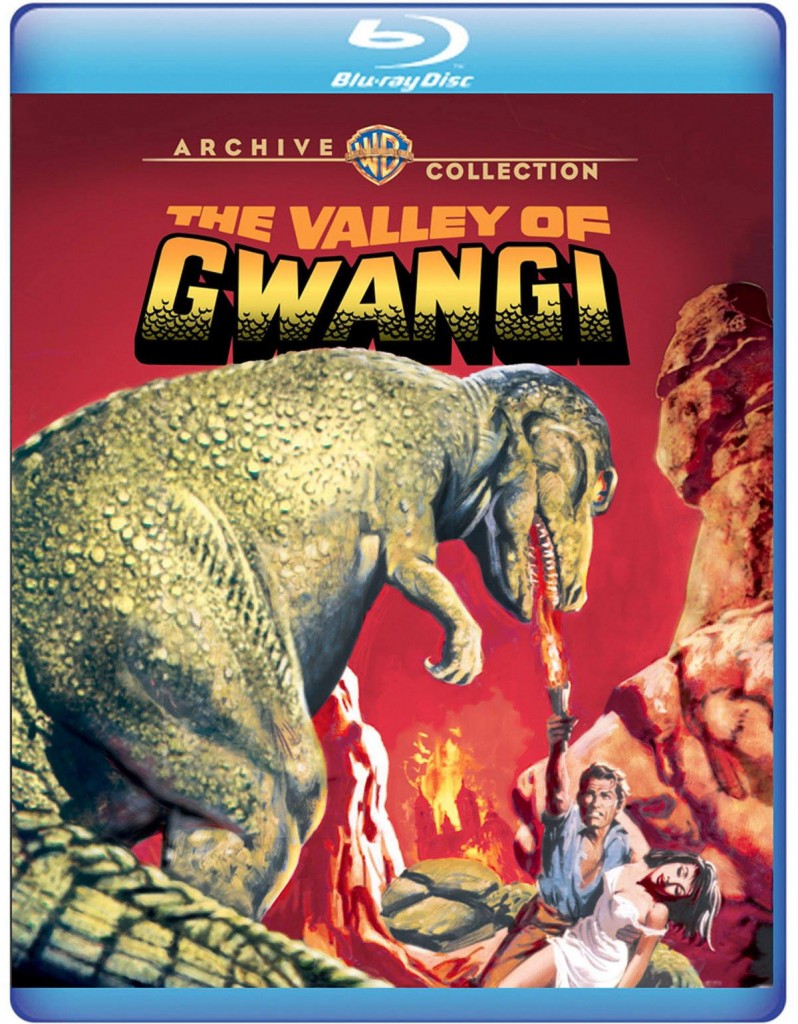

Yet here I am in possession of a Blu-ray from Warner Archive of The Valley of Gwangi and writing about it. Maybe I should start making gloomy declarations about the Blu-ray chances of other favorite movies, just to invoke the intervention of the muse who controls home video releases. (Melpomene, I believe.)

Everyone who loves movies probably has a specific film that seems as if it were made just for them. A Ray Harryhausen stop-motion giant monster in a Western? That’s what I call Ryan Harvey Niche Marketing. The only way The Valley of Gwangi could be more targeted to me is if 1) the monster was Godzilla, 2) Peter Cushing was one of the stars, and 3) Sergio Leone directed it. However, if such an event actually occurred, the shockwaves would’ve knocked Earth from its axial tilt and annihilated civilization. Perhaps it’s for the best we stopped at “Ray Harryhausen giant monster Western.”

Although The Valley of Gwangi has some of the flaws found in other Ray Harryhausen-Charles H. Schneer films (workmanlike direction, some stilted performances), it’s still one of the greatest dinosaur movies ever made, in the same league as One Million Years B.C. and Jurassic Park. Is Jurassic Park overall a superior movie? Yes, but in terms of creative dinosaur action, The Valley of Gwangi competes. The only dinosaur movie that ranks higher than these is the original King Kong.

The Valley of Gwangi started life in 1941 as an idea by Willis O’Brien, the visual effects wizard who created Kong and later mentored Ray Harryhausen. O’Brien proposed a Western slant on King Kong and The Lost World where cowboys discover a hidden valley of prehistoric animals. The horsemen rope an Allosaurus (the Gwangi of the title) and bring it back to star as the feature attraction in a Wild West show. The Allosaurus breaks free during a performance and wrecks havoc until its spectacular death. Simple and brilliant. So of course O’Brien never managed to get the project off the ground, although RKO had it in development for a year before shelving it.

O’Brien died in 1962. After the massive global success of One Million Years B.C. four years later, Ray Harryhausen saw an opportunity to bring his mentor’s languishing project to life. Warner Bros.-Seven Arts agreed to fund the movie for Harryhausen and his producing partner Charles H. Schneer. The script was changed from a contemporary (1940s) setting to the turn of the century and photographed in Harryhausen’s familiar stomping grounds of Spain.

O’Brien died in 1962. After the massive global success of One Million Years B.C. four years later, Ray Harryhausen saw an opportunity to bring his mentor’s languishing project to life. Warner Bros.-Seven Arts agreed to fund the movie for Harryhausen and his producing partner Charles H. Schneer. The script was changed from a contemporary (1940s) setting to the turn of the century and photographed in Harryhausen’s familiar stomping grounds of Spain.

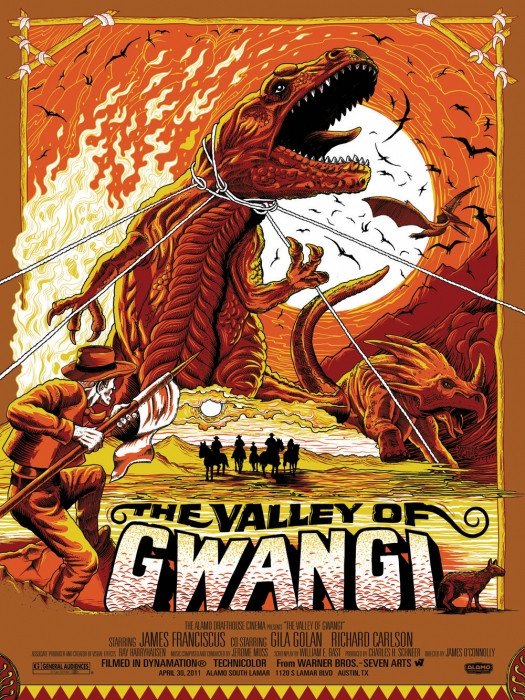

Although The Valley of Gwangi was designed to pick up on the success of One Million Years B.C., it failed at the box office when released in theaters in 1969. The main trouble was bad business timing. Before the movie’s release, Seven Arts sold Warner Bros. to the Kinney Company, and the new regime had no interest in the films remaining on the slate. The Valley of Gwangi (a confusing title Warners forced on the film over Harryhausen’s preferred The Valley Where Time Stood Still) was unceremoniously dumped into theaters on double bill with little promotion. Not even the amazing poster artwork from Frank McCarthy could lure people into the theaters. (And that is an amazing poster. Why didn’t Warner Archive use it as the Blu-ray cover?) The movie’s failure was large enough that it took five years before Schneer and Harryhausen were able to mount their next picture, The Golden Voyage of Sinbad.

The Western

The year 1969 was an ominous one for the Western as it declined in popularity but also a momentous one for its thematic evolution. The genre reach a saturation point with audiences in the early 1960s because of the deluge of Western programs on television. The Italian Western of the mid-‘60s gave an innovative boost to the stateside version, but by the last year of the decade the genre was moseying into a twilight region where the “Death of the West” would become the dominant theme. That year saw the release of three classics of the Dying West subgenre: The Wild Bunch, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and Once Upon a Time in the West.

The Valley of Gwangi isn’t on the same level as a Western as this trio, but it shares a similar spirit of people pushed to the frontiers — and often into oblivion (look at the finale of both The Wild Bunch and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) — as the American West fades into the realm of legend. The old heroes die under a barrage of bullets in a foreign country. Gwangi takes the metaphor to an extreme: a creature millions of years out-of-time dies in a foreign land, a fiery Catholic Church collapsing on it.

The opening scenes show faux-Western entertainment has replaced the real West. The story begins in Mexico (“Somewhere south of the Rio Grande” the titles tell us) where T. J. Breckenridge (Gila Golan) operates a Wild West show inherited from her father. Even as these shows go, it’s a sad business: barkers, diving horses, and shallow reenactments that can’t even even fill a quarter of the seats in a small bullring. No “real” adventure exists now, only these gaudy affairs.

The hero who strides into the town isn’t a romantic loner of the frontier. Tuck (James Franciscus) is a showman in a dandified cowboy outfit who’s looking for a few more Old West icons to exploit for cash. Tuck is a fake, the bogus adventurer selling bogus adventures based on shadows of the past. The strange twist is Tuck’s search for more nostalgia bucks leads to a past that isn’t decades old but millions of years old.

The hero who strides into the town isn’t a romantic loner of the frontier. Tuck (James Franciscus) is a showman in a dandified cowboy outfit who’s looking for a few more Old West icons to exploit for cash. Tuck is a fake, the bogus adventurer selling bogus adventures based on shadows of the past. The strange twist is Tuck’s search for more nostalgia bucks leads to a past that isn’t decades old but millions of years old.

James Franciscus is stronger than the usual handsome lead in this type of film; he’s got the charming rogue part down pat and flashes a killer grin. Tuck also has a solid character arc as a man who goes from loving the swindle to feeling disgusted at his part in plundering the Forbidden Valley and turning Gwangi into another cheap attraction. Unfortunately, leading lady Gila Golan is much less effective in her part, although it’s not wholly her fault. The Polish-born Israeli actress was dubbed and the results are awkward. But the character of T. J. isn’t much of a presence no matter who’s doing her voice. Franciscus puts energy into making the romance subplot between Tuck and T. J. work, but the characters’ development must move crosswise to each other, and Ms. Golan and her voice actress can’t hold up their half.

The Harryhausen-Schneer team always had good luck attracting excellent British actors (Patrick Troughton, Lionel Jeffries, Laurence Olivier) for character parts. Here we have Jason and the Argonauts veteran Laurence Naismith playing dotty paleontologist Professor Bromley. Naismith doesn’t hold back on the ham, such as his low breathy declarations of “Great Scott!”, but it’s appropriate in this setting. Freda Jackson, who later appeared as one of the blind witches in Clash of the Titans, makes a strong impression as another blind seeress character, Tia Zorina, the obligatory Prophet of Doom.

Another place where Harryhausen and Schneer had excellent luck was composers. Nobody surpassed the four scores that Bernard Herrmann wrote for them, but top-rank musicians continued to turn up. In this case, it’s Old School Hollywood composer Jerome Moross, who delivers a robust Western score with a Magnificent Seven-style main theme and similar techniques Max Steiner used for King Kong. Using the music to give the movie a classical Western and Monster Movie feel was the right way to go.

The Creatures

The Creatures

The Valley of Gwangi differs from the other color movies in the Harryhausen canon in a major way: the story centers on a single creature. The stop-motion creations in his other movies serve as individual obstacles in a larger story, and each sticks around to serve its individual effects set-piece before exiting. But Gwangi is the focus of the major sequences and remains an almost continuous presence from the moment he first enters. This makes the movie a callback to Harryhausen’s early black-and-white SF movies — particularly 20 Million Miles to Earth — but the genre-mashing period treatment and the addition of multiple “supporting” monsters creates a larger mythic landscape.

The stop-motion creatures outside of Gwangi are an interesting bunch. The Eohippus, a miniature prehistoric horse that serves as the lure into the Forbidden Valley, is a delightful tiny animal that adds variety in scale and those touches of characterization that are a special part of the Harryhausen magic. Just the moment of the Eohippus interacting with a real horse is fantastic. The other dinosaurs in the Forbidden Valley include a Styracosaurus (built from the body of the Triceratops from One Million Years B.C.), a Pteranodon, and an Ornithomimus. There’s also an animated elephant, which was a replacement for a real elephant that arrived on location too late — and too small.

However, Gwangi is the source of the movie’s chief set-pieces and deserving of his title-character status. Gwangi’s design combines an Allosaurus with elements of a Tyrannosaurs to come up with what Harryhausen called a “Tyrannosaurus al.” The model is one of the finest the special effects Harryhausen crafted, full of detail and allowing Gwangi a wide range of movements necessary to take on the movie’s starring role.

Gwangi is stunning throughout (with one exception I’ll get to at the end), but shines in three epic effects sequences: the fight with the Styracosaurus, the roping scene, and the Cathedral finale. The duel between Gwangi and a Styracosaurus is another cover version of the classic Tyrannosaurid vs. Ceratopsian tussle all children have acted out with dinosaur toys, but it’s a great one, even superseding the similar scene in One Million Years B.C. In any other dinosaur movie, this would be the highlight. Here, it’s the third best of Gwangi’s three big scenes.

The dino ropin’ is the sine qua non of the movie, the concept justifying the existence of everything else. It was what intrigued Harryhausen about the project when O’Brien first told him about it — and when he finally got to execute it, he didn’t disappoint. The scene is one of the high water marks in Harryhausen’s career.

The dino ropin’ is the sine qua non of the movie, the concept justifying the existence of everything else. It was what intrigued Harryhausen about the project when O’Brien first told him about it — and when he finally got to execute it, he didn’t disappoint. The scene is one of the high water marks in Harryhausen’s career.

Roping Gwangi lasts four and a half minutes on screen but took five months of animation to complete. The on-location planning necessary is astonishing enough on its own. It required choreographing stuntmen roping a tall stick placed on a jeep. To hide the jeep, the live action scenes had to be shot one half of the frame at a time so they could be composited together later to overlap the jeep. Even typing this out makes me exhausted for Harryhausen and all the meticulous labor and organization necessary to make this line up into usable background plates. After that came months of work animating Gwangi and matching the copper wire ropes from his neck to the real ropes on the live action. Once again, Harryhausen leaves me in awe that he executed all this by himself.

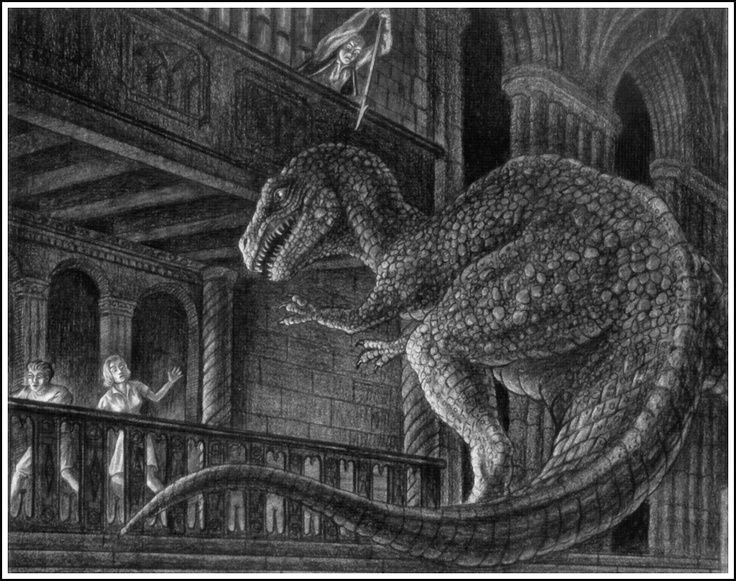

The finale in the cathedral is almost a peer to the roping scene. It doesn’t have the same complexity, but it’s a wonder of an idea: a carnosaur loose in a Gothic cathedral! It was entirely Harryhausen’s idea, since Gwangi in O’Brien’s version dies when a car slams him over a cliff. Shot in the Cuenca Cathedral, which was completed in 1257, the sequence has the touch of a late medieval nightmare, changing the film abruptly from a Western to a fantasy. The movie closes with Gwangi engulfed in a sea of fire, and it’s majestic and terrifying, like watching a demon writhing in infernal flames. The sequence required complex layers of compositing to combine Gwangi, the cathedral, and the lapping flames. The magnificent results are worth the effort.

Unfortunately, Gwangi has to endure one depressingly sad special effects moment. When trying to squeeze between rocks to escape the valley and pursue the horsemen, Gwangi causes a landslide that horrifically changes him into an immobile latex model. This was a fast and unsatisfactory solution to a lack of time for the tricky animation. As Harryhausen tersely puts it: “It looks awful.” I think we can permit Gwangi this one slip.

The Blu-Ray

The Blu-Ray

Matching its rocky original release, Gwangi has never had a stellar history on home video. The movie didn’t see a VHS release until the early 1990s. A pressed DVD from Warner Bros. was available starting in 2003, but eventually production was stopped and Warners released the disc through their manufacture-on-demand division, Warner Archive. (This is why I thought a Blu-ray release unlikely; if Warner Archive puts a film out on DVD, it usually means they don’t see potential in upgrading to Blu-ray.) The DVD was only an adequate transfer with slender bonus features.

Fortunately, Warner Archive gives more attention to its Blu-ray releases, and The Valley of Gwangi has never looked better — and probably couldn’t look better. Most of Harryhausen’s films have a rough look because the effects scenes boost image graininess in the live action footage, making it less jarring if the rest of the footage has a similar rough appearance. Gwangi sometimes appears cruder than other Harryhausen movies because weather conditions on location made it difficult to obtain the best quality background plates. The Blu-ray provides as clear an image as you would want for this vintage and style of film; it’s certainly the crispest I’ve seen for any of the VFX sequences, showing both the seams (yes, some of those background shots are fuzzy) but also many of the details.

Like most Warner Archive Blu-rays, there are almost no new extras available on The Valley of Gwangi, only the bits ported over from the 2003 DVD: an eight-minute featurette with a Harryhausen interview along with comments from ILM animators, the original theatrical trailer, and an Easter Egg from the DVD where Harryhausen tells a story about his daughter and a Gwangi prop. I’m glad Warner Archive kept these minimal bonus features, but minimal is the keyword here.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

The latex model in the landslide was so bad that at first I thought Gwangi was dead and the movie was over. I’d only previously watched the DVD probably back in 2003 or 2004, so I was necessarily fuzzy on the details of the story. Rewatching it, I was stunned at how good Harryhausen’s work was; and I’d forgotten how many other dinosaurs, horses, etc., showed up in the movie. I think I’d still probably rate Golden Voyage, Jason and Clash higher on my personal list, but that’s just because I’m such a fan of the fantasy elements; Gwangi would go very high up in the second tier.

@Joe – The jump to the latex model is definitely jarring. I can definitely feel Harryhausen’s pain at having to watch that knowing there was nothing else you could’ve done. It’s the sort of effect that worries you other people will laugh and use it to dismiss the whole movie as cheap, when so much of it is such astonishing work. I agree with your ranking system; I’d place the first two Sinbad films, Clash of the Titans, and Jason and the Argonauts higher than Gwangi, but it’s superior to most of the rest, certainly far above Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger. Exactly where it stands relative to One Million Years B.C. is a tough one, however. They may be both dinosaur films, but the difference in settings is immense, and each setting has its own special appeal.

I think to really rank Harryhausen movies I’d need to do it on a two-dimensional plane where the X-axis is quality of the movie as a narrative and the Y-axis is quality of Harryhausen SPFX. Which I think would have Golden Voyage, Seventh Voyage and Jason all clustered somewhere near the upper right hand corner, Clash up on the top but a bit closer to the middle horizontally, and Eye of the Tiger well to the left, but not too far down from the top.

Gwangi vs. One Million Years BC — yes, that’s a puzzler. I’m more likely to rewatch Gwangi, I think (although I’ll mourn the loss of Racquel Welch’s fur bikini), just because it doesn’t have the caveman gibble-gabble.

And I just got back from a pleasant walk around a nearby lake, during which I listened to the first couple episodes of the Ray Harryhausen podcast, put out by the Ray Harryhausen foundation. It’s great stuff — apparently, back in the few years before his death, they sat down with Ray and he recorded audio commentaries for most of his movies, which they’re planning to make available for download. The first couple of episodes are kind of a general introduction to the Foundation and an overview of Harryhausen’s film work; later episodes look like they’ll focus in more on a single film or a single topic. And they frequently drop in audio excerpts from the man himself.

“Well, the church fire got ‘im.”

“Oh, no. It wasn’t the church fire. It was the cowboy killed the beast.”

Ordered it on Blu-ray and watched it with my six-year-old son yesterday! Agree with everything in your review. Loved it when I was a kid how this film translated to screen what often happened in my sandbox: dinosaurs fighting cowboys (alternately, dinosaurs vs knights; vs army men; vs robots).

When I went back and ordered One Million Years B.C., I saw a customer review that gave it 3 stars because of Raquel and her furry bikini but lamented “Dinosaurs sadly lacking modern CGI techniques.” To which my mind immediately shot out the thought “Go f*** yourself.” Seriously. Hey, buddy, you gonna go into a museum next, look at a Van Gogh and go, “Sadly lacking in photographic realism”? Here’s a clue, kid: All the CGI wizards who create the effects you love in Jurassic World and Kong: Skull Island? They consider Harryhausen a god.

You don’t deserve any dinosaurs if you say that. I wonder what the reviewer thinks of King Kong.