A Rose By Any Other Name . . .

People can have all kinds of reasons to use another name, or to change their names permanently, for that matter. There are personal or family reasons, like marriage or adoption. There are political or social reasons, like marking a religious conversion, or immigration – though that last’s not as common now as it was in the early to mid-20th century. My own father, for example, changed his name to Malan because British authorities – to whom he had to report regularly as a displaced person after WWII – suggested that he try to sound less Polish since he was planning to stay in England. He chose a name much in the news at that time, and that’s why my brother and I are often asked if we’re South African.

People can have all kinds of reasons to use another name, or to change their names permanently, for that matter. There are personal or family reasons, like marriage or adoption. There are political or social reasons, like marking a religious conversion, or immigration – though that last’s not as common now as it was in the early to mid-20th century. My own father, for example, changed his name to Malan because British authorities – to whom he had to report regularly as a displaced person after WWII – suggested that he try to sound less Polish since he was planning to stay in England. He chose a name much in the news at that time, and that’s why my brother and I are often asked if we’re South African.

Setting these examples aside, however, actors and writers are probably the next large group of people who frequently change their names – or at least use other names as a pseudonym, or nom-de-plume, if you prefer. (A friend of mine once referred to her real name as her nom-de-nom.)

Why do writers and actors change names? For marketing reasons, usually. In the old days, actors, like immigrants, were asked to choose new names that were more easily said, or that struck the ear well, like Marilyn Monroe, John Wayne, Tony Curtis, or Groucho Marx. Okay, I’m kidding about Groucho.

Why do writers and actors change names? For marketing reasons, usually. In the old days, actors, like immigrants, were asked to choose new names that were more easily said, or that struck the ear well, like Marilyn Monroe, John Wayne, Tony Curtis, or Groucho Marx. Okay, I’m kidding about Groucho.

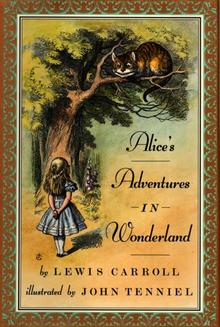

It’s true that some writers likely changed their names to disguise their “real” professions; MI6 member David Cornwell, became John le Carre, mathematician and professor Charles Dodgson became Lewis Carroll. Occasionally writers change their names because they’re changing genres, and don’t want their fans to be confused. Or something like that.

I’m sure that was not the reason Iain Banks wrote mainstream novels, and Iain M. Banks wrote SF.

But, Agatha Christie did became Mary Westmacott when she wanted to write romance novels, though it should be noted that Christie was her married name, which she continued to use even after her divorce and re-marriage. From the marketing angle, it’s better that you identify yourself with the name you were using when you became famous, regardless of changes in your personal life. Like Sigourney Weaver.

There was a time when it was felt that women couldn’t write SF. Or rather, they could, but that it wouldn’t sell. That resulted in Alice Mary Norton becoming Andre Norton, or Andrew North, or even Allen Weston. Alice Sheldon became James Tiptree Jr. Gender was also hidden behind initials. Catherine Lucille Moore became C.L. Moore, Carolyn Janice Cherry became C.J. Cherryh. This phenomenon was so common that for years I thought A.E. van Vogt was a woman.

Times change, and it’s more socially acceptable for people to keep their own names, and this applies to actors as well. Zach Galifianakis wasn’t required to change his name, for example, even though many people find it hard to pronounce. And neither were David Oyelowo or Chiwetel Ejiofor.

Times change, and it’s more socially acceptable for people to keep their own names, and this applies to actors as well. Zach Galifianakis wasn’t required to change his name, for example, even though many people find it hard to pronounce. And neither were David Oyelowo or Chiwetel Ejiofor.

Writers, however, are still writing under different names, and still for what are basically marketing reasons. Very few people can cross the genre barrier like Barbara Hambly and write both fantasy and mystery novels under the same name. She’s likely successful in this because her fantasy fans don’t know about her mystery novels, and vice versa.

How is it they don’t know? Because the books are shelved in different places. You know, marketing.

I know that I’ve only scratched the surface of writers using two or more names. I’m sure you can come up with examples of your own, like Stephen King, or Charles de Lint.

Violette Malan is the author of the Dhulyn and Parno series of sword and sorcery adventures (now available in omnibus editions), as well as the Mirror Lands series of primary world fantasies. As VM Escalada, she writes the upcoming Faraman Prophecy series. Find her on Facebook and follow her on Twitter @VioletteMalan.

A couple of nits … Caroline Janice Cherry (no “H”) became C. J. Cherryh. The extra “H” was, I have heard, Don Wollheim’s attempt to give her name a bit of exoticism. (I am by no means certain that she chose C. J. to hide her gender, either, though I don’t know in that case.) And Alice Sheldon said often enough that “James Tiptree, Jr.” became a sort of separate persona for her: again, I’m not certain that hiding her gender was the main reason for the pseudonym — hiding her identity (not just because of her job in the intelligence community, but for reasons of privacy) was surely important.

I will confess I assumed “M. A. Foster” was a woman at first because of the common use of initials by women writers.

Though I believe Alice Mary Norton did choose “Andre” for marketing reasons to an extent (and because it ambiguated her gender to book buyers), it should be noted that she took it as her legal name quite early in her career — that is, it was not technically a pseudonym. (Andrew North certainly was, though!)

So many to mention. I know Robin Hobb’s real name is Megan Lindholm, a name she has also published under. As I recall Morgan Howell is a pseudonym so that the author (I forget his name) could try to write more feminine accessible books.

Will be interesting to hear the various reasons.

Slightly off kilter but this brought to mind the list of 86 candidates for the authorship of Shakespeare’s works in Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Shakespeare_authorship_candidates

I suspect that it is not exhaustive. In fact, I am thinking of putting myself forward as a candidate.

To Rich: thanks for all the great details and information. Things are always more complicated than you can present in a short piece like this one. I’m a bit embarrassed by the extra “H”, a total typo on my part, I’m afraid. I’m just so used to seeing it with. I’ve fixed it now, thanks.

To Tiberius, I knew a guy in university who wrote romance novels under a suitably romantic feminine name, so it does happen both ways. I always think of Robin Hobb as Robin Hobb because that’s how I was introduced to her,though I knew she had another name.

To NeilH, you know, I actually thought about Shakespeare too! I just figured it was way too complicated to even get into. I think you probably have a good chance at being included among the possibilities.

Another example would be Seanan McGuire/Mira Grant, who makes no secret that both names are hers, but uses them so that her urban fantasy fans don’t inadvertently pick up a gruesome biological thriller, or vice versa.

(If you _do_ like both of her styles, and buy books under both names, that’s great — she just wants to be sure in all cases you know what you’re in for.)

And there’s Tom Holt/K.J. Parker, although Parker’s “true” identity was kept very, very close to the vest until relatively recently.

To Joe H., That puts McGuire in the “different names for different genres” category, though, as you say, she makes no secret of it. It’s like clear product labelling, an aid to the reader.

Do you think Holt’s disguise is explained by different genres?

I think Holt/Parker was at least partially because of the different genres. But I’m pretty sure it was also a bit of a publicity thing — as I recall, there was never any secret made that “K. J. Parker” was a pseudonym, and there was a fair amount of speculation as to who was actually behind the name prior to the reveal.

Oh, and Harry Turtledove published straight historical adventure novels as “H.N. Turteltaub”, which I’d consider a pretty open pseudonym, although not quite so open as “Iain M. Banks” (vs. Iain Banks).

To Joe H.: you’re right, I remember the “who is this?” chit chat at the time; it reminded me of the speculation that surrounded the publication of that political book, Primary Colours (?)

I did know that Turtledove had at some point used a pseudonym, but I didn’t know what it was. Thanks for letting me know, I have a friend who’s a big fan of Turtledove’s work, so now I can turn him on to Turtletaub.