Peplum Populist: Colossus of the Stone Age (Fire Monsters Against the Son of Hercules)

Here’s a pleasing discovery: Amazon Video has a widescreen print of the 1962 sword-and-sandal (peplum) film Colossus of the Stone Age available under its U.S. television syndication title, Fire Monsters Against the Son of Hercules. And the print is a good one. It’s not the level of a professional 4K restoration like the Phantasm Blu-ray that came out in December, but considering sword-and-sandal movies often look like someone dragged the film along the sidewalk on the way to the telecine department, Colossus of the Stone Age is damned near pristine. It isn’t part of the Amazon Prime library, however, so subscribers have to shell out $1.99 to rent it, or an extra 51¢ to own it. There’s a version streaming on Amazon Prime under the same title, but it’s the standard cropped and dragged-across-the-pavement type.

Here’s a pleasing discovery: Amazon Video has a widescreen print of the 1962 sword-and-sandal (peplum) film Colossus of the Stone Age available under its U.S. television syndication title, Fire Monsters Against the Son of Hercules. And the print is a good one. It’s not the level of a professional 4K restoration like the Phantasm Blu-ray that came out in December, but considering sword-and-sandal movies often look like someone dragged the film along the sidewalk on the way to the telecine department, Colossus of the Stone Age is damned near pristine. It isn’t part of the Amazon Prime library, however, so subscribers have to shell out $1.99 to rent it, or an extra 51¢ to own it. There’s a version streaming on Amazon Prime under the same title, but it’s the standard cropped and dragged-across-the-pavement type.

So as far as pepla available in English, Colossus of the Stone Age looks fantastic. But is it any good?

Perhaps the better question is, “Is it worth watching?” For this type of low-budget fantasy production, the question of quality is often separate from the question of whether to spend time with it.

But my answer to both questions is “no.”

The appeal of a peplum movie set in the Stone Age and the promise that it will have fire monsters is tempting, and the quality widescreen presentation is a legitimate bonus, but Colossus of the Stone Age (the U.K. theatrical release title) is one of the more tatty and flavorless examples of this genre. Pepla at their best have bizarre imagination, creative production designs and visuals, and robust action scenes. At their most mediocre they have heroes who don’t do anything and long scenes of extras running around in fields or through cheap cavern sets while clumsily swinging sticks at each other. Which is a sentence that works as a summary of this movie.

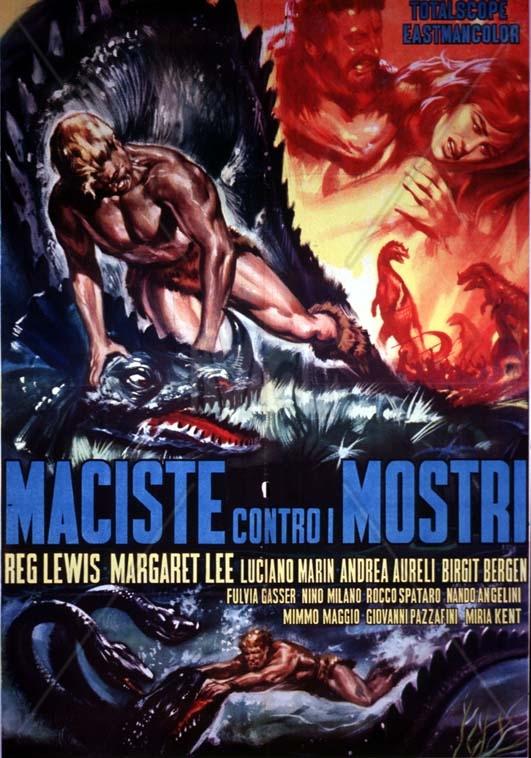

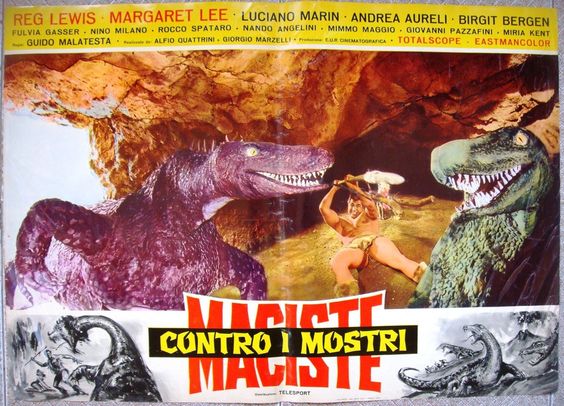

I’ll start with the “fire monsters,” since they’re what catches the fantasy-seeker’s eye. There are indeed monsters here. Not as many as appear on the posters, but you know better than to trust B-movie posters. The monsters are far from the technical quality of the Carlo Rambaldi creations in Perseus the Invincible, but they’re amusingly homemade and one of the movie’s few pleasures. The hero kills a long-necked lake monster at the start, then later tangles with underwater serpent heads that have no motion except where the currents toss them. They’re definitely the movie’s best ironic laugh.

The only real “fire” monster is a lizard-dragon beast that traps the hero and heroine in a cave. It’s impressively large and would’ve killed at a county fair parade in the “Most Creative Float” category. However, in the tradition of the hero who isn’t that heroic, the muscleman simply rams a stick in the lizard’s mouth and walks around it. Big silly monsters deserve big silly deaths.

Away from the monsters — which is unfortunately 95% of the running time — Colossus of the Stone Age is the same ho-hum default story of numerous sword-and-sandal films: a feud between two tribes and a super-strength hero who intervenes on the side of the weaker tribe.

The hero this time is Maciste, a character who originated in the silent era of Italian cinema. Maciste is essentially Hercules with a different name, which is why foreign versions of Maciste films often turned him into the Herc in the title and dubbing. Maciste lacks a consistent backstory, legend, or even time period. He primarily appears in classical mythological settings, but he’s shown up in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Europe as well. Here he’s unleashed during the Ice Age.

The hero this time is Maciste, a character who originated in the silent era of Italian cinema. Maciste is essentially Hercules with a different name, which is why foreign versions of Maciste films often turned him into the Herc in the title and dubbing. Maciste lacks a consistent backstory, legend, or even time period. He primarily appears in classical mythological settings, but he’s shown up in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Europe as well. Here he’s unleashed during the Ice Age.

The warring tribes are the Sun People and the Moon-worshipping Cave People. Sun People = good. Cave People = bad. We know this because according to genre law, whoever strikes first against the other is the bad group. The Sun People under their chieftain Dorak (Rocco Spatoro) carry their secret of fire away from the advance of glaciers. They settle in a green land, but the Cave People don’t want them there. They raid the Sun People’s village and haul victims to offer as sacrificial beheadings to their god. That’s another clue the Cave People are the bad guys.

Into this primitive war wanders Maciste (Reg Lewis), and not for any good reason. Following his intro, where he harpoons the water serpent and mutters something about destiny, Maciste vanishes for a solid twenty minutes. After the Cave People raid the Sun People’s village and make off with their women, Maciste pops up among the Sun People to take control of the rescue and retaliation efforts without anyone asking who is or why he cares. He pauses to show the Sun People that their secret of fire isn’t anything special by striking two rocks together to re-ignite their sacred flame.

The rest of the story has Maciste leading the fight against the Cave People and their rapacious chief, Fuwan (Nello Pazzifini). Maciste blows it the first time, and a volcano has to do most of the heroic work — including saving him from execution. Maciste pairs up with Fuwan’s prisoner and intended bride, Moah (English actress Margaret Lee) so he can have company while the rest of the movie unfolds elsewhere. There’s a limp subplot with young lovers among the Sun People, Idar son of the chief (Luciano Marin) and Rhia (Andrea Aureli). Idar seems like he should’ve been the protagonist, but there’s not enough time with him, and viewers can easily become confused between Rhia and Moah because the actresses look similar and have identical hairstyles.

Another peplum ritual is halting the action so sparsely-clad women can perform a ceremonial dance. There are two dance shows this time, one for each tribe. The choreography and synchronization of both are as lackluster as the rest of the film. The Cave People have a moderately better routine, but they’ve had more time to develop their moves because they’ve lived in one place for longer.

The creative promise of the prehistoric setting turns out to be only an excuse for cut-rate sets. The caverns of the Cave People are phony even for this genre, and everything else is wood huts on grass. The location is a bit different than other sword-and-sandal films, since it was photographed in Slovenia (then a part of Yugoslavia) rather than in Spain. But the novelty of greener fields ebbs fast.

The production in general radiates cheapness. A low budget doesn’t have to be an obstacle to a movie’s quality (just look at Mario Bava), but director Guido Malatesta handles whatever is on screen with such a looseness that everything feels substantially chintzier. This is most painful in the “action” scenes, which consist of a field of extras in fur rags randomly hammering each other with axes while the camera sits there.

The production in general radiates cheapness. A low budget doesn’t have to be an obstacle to a movie’s quality (just look at Mario Bava), but director Guido Malatesta handles whatever is on screen with such a looseness that everything feels substantially chintzier. This is most painful in the “action” scenes, which consist of a field of extras in fur rags randomly hammering each other with axes while the camera sits there.

Guido Malatesta helmed a number of other pepla, including Goliath Against the Giants (1961), Revolt of the Barbarians (1964), Fire Over Rome (1965), and Maciste, Avenger of the Mayans (1965). His best-known movie is Colossus and the Headhunters (1963), which gained fame as an episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000. If people who have seen that episode find the plot of Colossus of the Stone Age a touch familiar, there’s a good reason. The two films not only have matching stories, they look similar and have the identical trouble of a useless hero (Maciste in both cases) and extended scenes of extras lazily smacking weapons together. This appears to be Malatesta’s directorial “style.”

Colossus of the Stone Age may have nudged up from its flaws if it weren’t for the problem of its leading man, American bodybuilder Reg Lewis. Although Lewis had the physique suited to the genre, this is his only sword-and-sandal film. One-hit wonder actors were unusual for peplum; if you were buff enough, it guaranteed you at least a few Hercules, Maciste, Goliath, Ursus, or Random Gladiator pictures. But Lewis is so wooden and visibly uncomfortable on screen that it’s for the best he swung by Italy (and Slovenia) for only this single outing. The sense the actor is moving from mark to mark without any understanding of why pervades every scene he’s in.

But I can also blame director Malatesta for letting the camera sit in one place for scene after scene of Lewis walking from one side of the screen to the other. There had to be a way to shoot or cut around the leaden nature of Lewis’s performance. (At least hire a decent English dubbing actor to cover up for him. Lewis’s voice actor is substantially inferior to the rest of the cast.) Although Colossus and the Headhunters is the worse of the two movies, it at least has a better leading man playing Maciste, Kirk Morris.

However, no actor could fully salvage the role, because Maciste hasn’t much to do. He never flexes outrageous moves during the fights, and he only has two opportunities to show off his Olympian strength: hurling the top of a triptych onto some Cave People and pushing open a door with a giant lever. The biggest hurt the villains suffer comes when a plastic model of a volcano conveniently erupts and rains down special effects for a few minutes. At the time, Maciste is buried in the ground up to his neck. There isn’t even a suggestion that Maciste might do something extraordinary to escape.

Colossus of the Stone Age was released in Italy as Maciste contro i mostri (“Maciste Against the Monsters”). Embassy Pictures purchased it for stateside release as part of its “Sons of Hercules” syndication package and re-titled it Fire Monsters Against the Son of Hercules. A bit of awful dubbing-on-top-of-dubbing has the hero call himself “Maxus, Son of Hercules,” which is nonsense because Hercules wouldn’t have existed yet. But the hero is really Maciste and Maciste can appear in any time period, so …

Okay, I blame this all on the Fire Monsters alternate title. The glamour of monsters is often a genre fan’s undoing. I’ll find something better next time, promise.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Godzilla on interviews.

One of the few perks of growing up in 1970s Italy was watching a lot of these films in cheap local movie theatres. Italian peplums, Japanese monster movies, Corman productions…

But re: Maciste, the character had a lot of potential (not that it was ever fully developed) in his time-hopping nature. Indeed, I saw him fight the Phoenicians one week and the Pirates of the Spanish Main the other, and it was cool. Also, in the best movies (of which Maciste contro i mostri is NOT an example), the character is often presented as a smart guy and not just as a two-fisted muscle-man.

A time hopping, smart troubleshooter… not bad as a concept for a series.

A bit of a derail, but speaking of cheesy monster movies, When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth just hit Blu-ray last week. It’s even the international cut …

I love these movies, but the wretched quality of 98 percent of the ones available usually makes them absolutely unwatchable. Too bad.

@Thomas Parker – Yes, that is the unfortunate dilemma. Plenty that’s great about them, but plenty of them aren’t great. You have to sift through the nearly unwatchable to find some gems. That was the concept that drove me to start doing this occasional feature — but I knew a consequence was dealing with Colossus of the Stone Age and similar bland detours.

@Joe H. – The reviews for the Blu-ray are quite good. It’s just that it’s so much harder to make it through the human scenes in When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth compared to One Million Years B.C. that prevented me from really loving it. I’ll probably get the disc at some point, but the upcoming Gwangi disc is what has me especially excited.

@Davide Mana – The unmoored in time aspect of Maciste is one of his more interesting aspects, and a series would be spectacular — although I don’t want to get my hopes up that this will happen. (Although, with every other pop culture figure of the past getting a shot, why not Maciste?) I’ll be dealing with one of the best Maciste films, The Witch’s Curse (Masciste in Hell) eventually.

Yeah, the human scenes were … not good. The stop-motion was better than I was expecting, though, especially the crab attack at the end.

And yes, Gwangi will be almost infinitely superior.