Final Thoughts on Narnia. The Last Battle: A Criticism and a Defense

Well, these were my books. You know, the ones that got me forever hooked on fantasy worlds and addicted to stories untethered from the things we know. I was eight, in the second grade, when I began reading them, and they were the first to begin teaching me that precious lifelong lesson: that though you might not trod in Faerie with your flesh-and-bone feet, there are many other pathways thither.

Well, these were my books. You know, the ones that got me forever hooked on fantasy worlds and addicted to stories untethered from the things we know. I was eight, in the second grade, when I began reading them, and they were the first to begin teaching me that precious lifelong lesson: that though you might not trod in Faerie with your flesh-and-bone feet, there are many other pathways thither.

It was this shared knowledge that made an eight-year-old American boy feel he had much more in common with an old British professor who had died a decade before he was born than he did with most people he met day to day. And that remains true to this day. My spirit is more kindred with a New York woman born in 1918 (Madeleine L’Engle) than with my next door neighbor, closer to a Japanese man born in 1941 (Hayao Miyazaki) than to many of my blood kin.

It’s because we all share the secret – both those of us who weave the stories and those who are the audience willing and eager to fall under their spell – that there are doors to Faerie hidden in our own imaginations. Whenever and wherever we might have lived, wherever we might be. It’s a gift that goes back to the Beowulf poet, and back further to Homer, and back further still; indeed, it is one of the first magical abilities that separated man from the beasts.

But lest I diverge into a long-winded tribute to the power of fantasy, let me get to the issue at hand today. I have recently revisited Narnia, this time with a fellow traveler newly discovering the wonders of other realms. My daughter, just turning eight – the exact age I was when I first went through the wardrobe – has become a big fan.

At the beginning of the year I began reading them to her, a couple chapters each night at bedtime. (And yes, almost every night closes with that familiar refrain, “One more! Please just one more!”) She was already familiar with the story through other mediums: she had watched the recent Hollywood live-action films of the first three books as well as that odd, quirky, and delightfully trippy ‘70s animated version of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe. She had also listened to a dramatic audio adaptation of all seven books that stretches over 21 discs.

But really, there’s nothing like having your Dad read them to you. Especially if your dad is a theatrical performer in his own right, with some professional stage experience under his belt and a penchant for animated readings with distinctly memorable voices provided for each character! (Never mind that Trumpkin the Dwarf wound up having the drawl of John Wayne, or that Aslan sounds vaguely like James Earl Jones.)

And here we are, at the end of February, finishing up The Last Battle. The most controversial book in the series, for a number of reasons. Having it fresh in my mind now, I decided I would address those controversies: my last word, if you will, on The Last Battle. What better place to tackle them than here, at Black Gate, home of the final word on many things fantasy?

If we picture, for a moment, these favorite tales of childhood as ships that took us across the sea to visit wondrous places – some of the vessels sleek and swift, others lumbering and slow; some whisked you right along with a strong wind at your back while with others you had to dip in an oar and do some rowing; some of them were cozy and comfortable while others required you to tolerate some discomfort in the accommodations – then we might say that some of the ships have acquired unsightly barnacles and unwelcome stowaways. These awkward and embarrassing blemishes on otherwise beloved craft are the controversies that have arisen, be they outdated attitudes that now meet with disapproval or prejudices of a past era that have been ignominiously rejected.

If we picture, for a moment, these favorite tales of childhood as ships that took us across the sea to visit wondrous places – some of the vessels sleek and swift, others lumbering and slow; some whisked you right along with a strong wind at your back while with others you had to dip in an oar and do some rowing; some of them were cozy and comfortable while others required you to tolerate some discomfort in the accommodations – then we might say that some of the ships have acquired unsightly barnacles and unwelcome stowaways. These awkward and embarrassing blemishes on otherwise beloved craft are the controversies that have arisen, be they outdated attitudes that now meet with disapproval or prejudices of a past era that have been ignominiously rejected.

There are three controversies here: 1) the whole religion thing, 2) charges of racism, and 3) the “problem of Susan.” I’ll take them in order.

-

The Religion in the Room

While re-reading these books for the first time in perhaps twenty years, I occasionally felt the religious “allegory” to be intrusive. Not much or certainly not often – I still felt many of the familiar stirrings of wonder well up within me; I got lost in the story often enough that my daughter did not always have to beg me for one more chapter. And there were times, to my great surprise, that I got choked up when it came to the appearance of Aslan. I would have to catch my breath and gather myself to read on, clearly as strongly affected by the powerful impact of His dramatic entrances as was my daughter, whose face would light up while she clapped her hands together in anticipation.

Where the allegory or “near-allegory” becomes problematic is when you sense the story being bent to fit some religious lesson. Whenever an astute reader gets a whiff of that, of course, it yanks one right out of the story. But Lewis is not often clumsy on this account.

Where the allegory or “near-allegory” becomes problematic is when you sense the story being bent to fit some religious lesson. Whenever an astute reader gets a whiff of that, of course, it yanks one right out of the story. But Lewis is not often clumsy on this account.

Everyone should know by now that there are veiled allusions to Christianity throughout the Narnia Chronicles. Some are subtle, others not at all. Aslan dying and rising again for the sin of Edmund is, of course, the linchpin (as is the resurrection of Christ the linchpin of the Gospel story).

Some people (Christians among them) are put off by any sort of allegory like this. C.S. Lewis’s rejoinder to the charge was always that it was not strictly allegory: he wasn’t telling the Narnia story as a one-to-one allegorical retelling of the New Testament; rather, he was imagining what if there were this other world, and the person who in our world is Christ also visited that world. What form of incarnation might He take there, and what might happen?

All well and good, but most of the people who are bothered by it aren’t going to be satisfied by this rationale. And the people who don’t like it fall into two categories. The first are those who don’t have an issue with allegory per se (they like, for example, Animal Farm. No problem with that one.) . They just don’t like Christianity. And they certainly don’t want it being slipped surreptitiously into their children’s fairy tales.

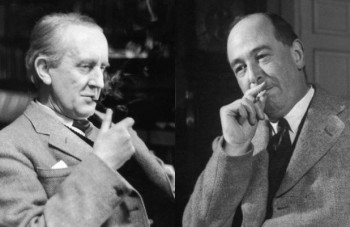

The second category of people detest allegory regardless whether or not they “agree” with the message. J.R.R. Tolkien was among these: admirer of much of Lewis’s work though he was, he loathed the Narnia books. (The allegory was only one reason for that – the other reasons would make a whole other article.) It wasn’t the Christianity he had a problem with. In fact, I like to remind those hardcore Tolkien fans who hold a dim view of his long friendship with “that vocal Christian advocate Lewis” that Tolkien was as strong a believer as Lewis (he was a devout Catholic while Lewis chose to join the Anglican church). Tolkien was just much more private about his religious views, and they were nowhere explicit in his own work. Indeed, Tolkien was one of the people who helped lead Lewis (who was, when they met, an atheist) “to Christ” – a fact that will be met with horror by some Tolkien fans who revile organized religion and somehow weren’t aware of that.

The second category of people detest allegory regardless whether or not they “agree” with the message. J.R.R. Tolkien was among these: admirer of much of Lewis’s work though he was, he loathed the Narnia books. (The allegory was only one reason for that – the other reasons would make a whole other article.) It wasn’t the Christianity he had a problem with. In fact, I like to remind those hardcore Tolkien fans who hold a dim view of his long friendship with “that vocal Christian advocate Lewis” that Tolkien was as strong a believer as Lewis (he was a devout Catholic while Lewis chose to join the Anglican church). Tolkien was just much more private about his religious views, and they were nowhere explicit in his own work. Indeed, Tolkien was one of the people who helped lead Lewis (who was, when they met, an atheist) “to Christ” – a fact that will be met with horror by some Tolkien fans who revile organized religion and somehow weren’t aware of that.

Like many first-time readers, I was not aware of any religious meaning in the books when I first read them, and probably not until my third or fourth reading. Other writers have described the sense of disillusionment or betrayal they felt when they got older and realized that Lewis was injecting his own religious beliefs into the narrative, as if he were trying to “trick” them.

On the other hand, many other people welcomed the “deeper meanings” their beloved childhood fairy stories were suddenly imbued with – they loved Aslan and now they love him even more if they are a follower of Christ. Or they find the love they felt for Aslan is transferred now to their love for Jesus (as Lewis clearly intended).

And still others, those who aren’t particularly religious themselves or are not self-described Christians, just don’t care all that much: they love the fictional character of Aslan and the stories of Narnia, and if the stories were inspired by (what they consider to be) other fictional stories that some people believe are true, great. Inspiration has to come from somewhere, right? If it makes a good story, it makes a good story.

But if the religious undertones (or overtones) are a hang-up for some people, it applies to the series as a whole, which is why I won’t give much more attention to it here as I’m concerned with the controversies inherent in the final book specifically. They’re more important to address because they can pose a stumbling block not only to the people who already reject the books out of hand but to those who really treasure and cherish them (religious and non-religious alike).

But if the religious undertones (or overtones) are a hang-up for some people, it applies to the series as a whole, which is why I won’t give much more attention to it here as I’m concerned with the controversies inherent in the final book specifically. They’re more important to address because they can pose a stumbling block not only to the people who already reject the books out of hand but to those who really treasure and cherish them (religious and non-religious alike).

Before I turn to those two controversies, I will raise one specter that haunted me while reading The Last Battle to my daughter, namely, how much darker this book is than the other six. I’ll address it not as its own separately-numbered controversy, but instead bring it up here because it partly arises from the religious roots of the story.

As I mentioned at the start of this section, Lewis is not often clumsy when it comes to weaving Christian ideas into the story. But with The Last Battle he clearly decided to deliver a version of the Book of Revelation for Narnia. Now, many people (most people except maybe Jehovah’s Witnesses and some fundamentalist Christians) read the bizarre creatures and horrifying events of Revelation as allegorical, but, Narnia being Narnia – where animals talk and dragons are real – the events are literal. And still just as horrifying.

Perhaps it was the nature of using that book as his inspiration, but Lewis really lays on the horrors: the dryads dying as their trees are chopped down; the animals being sold into slavery; some characters being murdered. Battles and deaths occurred in all the other books, but Lewis kept most of it off center stage and really only got graphic with the death of Aslan (which is quickly relieved in the next chapter with His resurrection).

Here Lewis pulls no punches. Whereas the other six installments do feel like books written for children, this one – if it is assessed by itself – by today’s standards definitely feels more “young adult,” not only with its themes but with the disturbing slaughters (like the Bear that, with its dying breath, mutters, “I – I don’t understand”) and deaths of main characters. In fact – spoiler alert – the book ends with the revelation that all the characters from our world died in a train smash-up just prior to this, their final visit to Narnia! That might not pose a big problem for parents who are teaching their children that people don’t really “die”; they just go on to Heaven (which, indeed, is what happens in the book). But for adults who aren’t ready to broach discussions of mortality with their little one, be forewarned and prepared.

Here Lewis pulls no punches. Whereas the other six installments do feel like books written for children, this one – if it is assessed by itself – by today’s standards definitely feels more “young adult,” not only with its themes but with the disturbing slaughters (like the Bear that, with its dying breath, mutters, “I – I don’t understand”) and deaths of main characters. In fact – spoiler alert – the book ends with the revelation that all the characters from our world died in a train smash-up just prior to this, their final visit to Narnia! That might not pose a big problem for parents who are teaching their children that people don’t really “die”; they just go on to Heaven (which, indeed, is what happens in the book). But for adults who aren’t ready to broach discussions of mortality with their little one, be forewarned and prepared.

The opening chapters of The Last Battle are so bleak, moreso than I remembered. It all turns out “all right” only in the sense that the whole world is wiped out, but the protagonists and the true believers go on into a more permanent world of which Narnia was only a “Shadow-Land.” It is a moving and powerful idea for those of us who are aware that our own world will one day end; the sun will burn out; the whole universe will eventually reach full entropy and collapse in on itself. But it’s strong stuff for a very young person to grapple with.

-

The Racism in the Room

Okay, when I picked these books back up I couldn’t remember if this charge was founded or not. But yes, there is some here, although it didn’t become an issue until The Last Battle. That said, there are some qualifications of historical context that should be duly noted. When one does this, inevitably it sounds as if one is defending the offense in question. I am not. I am simply being thorough in my critique.

We recognize today that racism comes in different forms, some more insidious and subtle than others. Most broadly and generally speaking, there is racism based on skin color and there is racism based on culture or cultural background. The former is the most easy to recognize: someone immediately assumes he is superior to another person simply because he has less melatonin in his skin (and is therefore both more vulnerable to and more deserving of skin cancer). An example of the latter would be the racism spewed against early Irish immigrants to the United States, even though people of Irish descent are clearly lumped in and thought of as Caucasian today.

We recognize today that racism comes in different forms, some more insidious and subtle than others. Most broadly and generally speaking, there is racism based on skin color and there is racism based on culture or cultural background. The former is the most easy to recognize: someone immediately assumes he is superior to another person simply because he has less melatonin in his skin (and is therefore both more vulnerable to and more deserving of skin cancer). An example of the latter would be the racism spewed against early Irish immigrants to the United States, even though people of Irish descent are clearly lumped in and thought of as Caucasian today.

Much has been made of the Calormenes being caricatures of Middle-Eastern or Muslim culture and religion. The religion issue doesn’t strike me as particularly relevant here: if you are going to set up a “True Religion” and a “False Religion,” then the false religion is obviously going to be portrayed as inferior to the true one. Go into any one of thousands of Christian churches next Sunday and you will be among people who believe their religion is true and Islam is not, and vice versa if you instead visit a mosque (of course, the more enlightened among those people gathered in churches or temples or mosques will recognize that there are places of overlap — shared values and shared roots — and prefer tolerance and harmony to religious war).

The culture of the Calormenes seems to be a mash-up of various Arabian and Asian cultures; it is not meant to be any of them, of course, but its own thing in this other world. I personally wish Lewis would have pushed his imagination a bit further when it came to the cultures of Narnia, not simply using pastiches of Earthly cultures but making them a bit more alien. Anyway, the god Tash is not Islamic in any sense, but seems to be a ravenous D&D Deities and Demigods version of a Hindu deity.

The culture of the Calormenes seems to be a mash-up of various Arabian and Asian cultures; it is not meant to be any of them, of course, but its own thing in this other world. I personally wish Lewis would have pushed his imagination a bit further when it came to the cultures of Narnia, not simply using pastiches of Earthly cultures but making them a bit more alien. Anyway, the god Tash is not Islamic in any sense, but seems to be a ravenous D&D Deities and Demigods version of a Hindu deity.

If there’s a real concern for me as a parent reading this book to my child (and there is), it’s the insinuation of the first and most blatant type of racism: attention is drawn to the Calormenes’ dark skin in contrast to the “fair skin” of the Narnians. Several times they are even called “Darkies.”

None of this is good, and as the Narrator for my daughter I have expurgated this language whenever it has appeared in the text.

But, having confirmed that criticism, I will now defend Lewis against the most vile charges of racism. I remind my social-justice friends, who are correct to point out that there are different – more subtle and more blatant — forms of racism, that such analysis cuts both ways. Finer, more focused critical analysis can identify incidents of “racial micro-aggression” from a person who is not blatantly racist; likewise, it can be used to demonstrate that someone who has been charged with blatant racism has actually done something that falls somewhere further down the scale. This, I hasten to emphasize, does not excuse it; it puts it in perspective.

The first thing we might ask is Who is racist in this book? The only people who refer to the Calormenes as “darkies” are the renegade dwarfs who have turned against Aslan, massacred the Talking Horses, and otherwise proven themselves to be villains.

I do not think Lewis equates skin color with a reflection of one’s racial purity. I will offer three pieces of evidence for this.

- One of the heroes of The Last Battle is a Calormene soldier named Emeth.

- One of the heroes and main protagonists of The Horse and His Boy is a girl of Calormene nobility (a Tarkheena) named Aravis.

- In that same book, High Queen Susan is going to be betrothed to the son of the Tisroc, creating by their union a stronger bond between Narnia and Calormen. There is much counsel against this, but never because the prince is a Calormene. It is because of his personal character (he turns out to be a scoundrel).

Frankly, what I think happened here could be called laziness in falling back on a common racist trope of the time (these books were written in the 1950s): If your bad guys happen to be dark-skinned, that physical characteristic is played up in descriptions to add to their menace – “their dark skin and flashing white teeth and eyes.” No, it’s not appropriate, and it’s certainly not acceptable today. And, rest assured, when the story was read by this dad to his daughter, any references to dark skin in this context were left unread on the page.

-

Why Isn’t Susan in the Room?

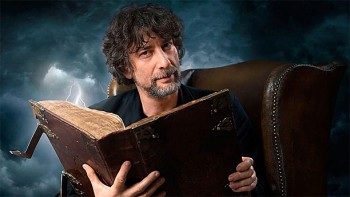

Now we get to the biggest elephant in the room (for some people), which is the absence of Susan. Neil Gaiman referred to it as “the problem of Susan” and even wrote a highly regarded short story about it under that title. He imagined the story from Susan’s perspective, a grieving older woman who lost her brothers and sister to a train accident (never knowing, of course, that they all went to live happily ever after in the World Beyond Narnia).

Now we get to the biggest elephant in the room (for some people), which is the absence of Susan. Neil Gaiman referred to it as “the problem of Susan” and even wrote a highly regarded short story about it under that title. He imagined the story from Susan’s perspective, a grieving older woman who lost her brothers and sister to a train accident (never knowing, of course, that they all went to live happily ever after in the World Beyond Narnia).

Susan’s absence is enigmatically explained, the first couple times it is brought up, as her being “no longer a friend of Narnia.” Toward the end of the book, when the others who have visited Narnia as children are all revealed as kings and queens, this is elaborated on. She no longer believes in Narnia – she has dismissed her adventures there (in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Prince Caspian) as childhood fancies, and thinks her siblings rather nutty for still pretending to believe they really happened.

Okay, one can see the religious connotation that can be drawn: she’s like a Christian who has lost her faith. But, setting aside the religious interpretation, what are we to make of it? And was Lewis saying something else with Susan’s rejection of Narnia?

Clearly he was. Unfortunately, some of his critics have used this expulsion of Susan from the final book as evidence that Lewis was a misogynist who disliked women.

That is rubbish.

First, just a quick bit of biographical context, because there’s too much garbage floating around out there about Lewis on this subject. Lewis grew up and worked and lived his entire life in a college culture (first at Oxford, then at Cambridge) that was gender segregated. Boys were sequestered with boys, men with men; there was little interaction with the other sex until one got married (and Lewis did not marry until very late in life, living most of his days a confirmed bachelor). His mother died when he was young; his only sibling was a brother.

First, just a quick bit of biographical context, because there’s too much garbage floating around out there about Lewis on this subject. Lewis grew up and worked and lived his entire life in a college culture (first at Oxford, then at Cambridge) that was gender segregated. Boys were sequestered with boys, men with men; there was little interaction with the other sex until one got married (and Lewis did not marry until very late in life, living most of his days a confirmed bachelor). His mother died when he was young; his only sibling was a brother.

Despite all this, he was not completely devoid of female companionship; indeed, after he returned from the First World War he moved in with the mother of a friend who died in the war. There is strong evidence that this relationship became intimate, although it developed into, for the remaining years of the woman’s life, a case of Lewis caring for her as a son would care for a dependent, ailing mother.

It must be noted that Lewis, one of the “ol’ boys” that he was, became close friends throughout his life with several smart, brilliant, and talented women, like the novelist Dorothy Sayers. The fact that he had regular correspondence with such distinguished and successful women puts the lie to the claim that he had some sexist notion about the place of women being barefoot in the kitchen. And if there were any doubt, when he did marry (at the age of 58), he married the American writer and poet Joy Davidman, an independent, outspoken divorcee who also, incidentally, was Jewish (for some of his colleagues, this was “three strikes”: she was divorced; she was Jewish; she was American).

So what about the female characters in the Narnia books? Well, they’re generally the bravest and cleverest protagonists (stereotypically masculine traits in most older literature) as well as being the most compassionate and empathetic (stereotypically feminine traits in most lit) . They tend to see through to the best path when the boys are being hot-headed and stubborn (negative masculine traits). Only the sisters courageously follow Aslan on his dreadful night-walk to the Stone Table. It is only Lucy who sees Aslan at first when they return in Prince Caspian. Polly is clearly smarter and more self-disciplined than Digory (who foolishly releases the White Witch) in The Magician’s Nephew. In fact, in that book, with the exception of the Witch herself (who is not human), the females (Polly and Digory’s aunt) come off far better than the men (Digory and his uncle).

So what about the female characters in the Narnia books? Well, they’re generally the bravest and cleverest protagonists (stereotypically masculine traits in most older literature) as well as being the most compassionate and empathetic (stereotypically feminine traits in most lit) . They tend to see through to the best path when the boys are being hot-headed and stubborn (negative masculine traits). Only the sisters courageously follow Aslan on his dreadful night-walk to the Stone Table. It is only Lucy who sees Aslan at first when they return in Prince Caspian. Polly is clearly smarter and more self-disciplined than Digory (who foolishly releases the White Witch) in The Magician’s Nephew. In fact, in that book, with the exception of the Witch herself (who is not human), the females (Polly and Digory’s aunt) come off far better than the men (Digory and his uncle).

What about the business of men’s roles versus women’s roles when it comes to fighting? Some detractors point out that in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Lucy is given a healing phial while only Peter is given a sword. Susan is given a bow. Father Christmas, when he presents these gifts, makes some mention of Lucy not being in the main battle because things get ugly when girls are involved in that nasty business. So it seems that the women are relegated to secondary, support roles in combat.

Two things. Three, actually. First, that is an issue that has been hotly debated even here in the United States up until about a year ago. Wrong or right, it’s certainly not an antiquated attitude – there was strong opposition when women were finally allowed into any area of front-line ground combat just last year.

But let’s not debate that here. Let’s just go to the second thing, which is that Narnia generally reflects medieval and earlier epochs in its cultures and technology. And women fighting in hand-to-hand combat in real battles here in our world has almost always been rare. We remember historical figures like Joan of Arc because they are anomalies. Yes, when it comes to that stupid and nasty business of walking across a field to try to lop off another person’s head, it’s mostly been men engaged in that endeavor.

But what about the question of whether the female characters are capable of facing up to what must be done in dire situations? Will they just wilt, cower somewhere while the bold boys sally forth and protect them?

Not in Narnia. Nu-uh, not our girls. Susan has to use that bow on more than one occasion, and she is a great shot. And when it’s time to hunt the White Stag, all four of the siblings go on the hunt. In The Last Battle, Jill Pole proves herself to be one of the most deadly foes of the Calormenes, dropping them left and right with well-placed shots with her bow. She’s a freakin’ sniper. And – bother it all! – even when it comes to hand-to-hand combat, Aravis in The Horse and His Boy is a trained and competent wielder of a sword.

Not in Narnia. Nu-uh, not our girls. Susan has to use that bow on more than one occasion, and she is a great shot. And when it’s time to hunt the White Stag, all four of the siblings go on the hunt. In The Last Battle, Jill Pole proves herself to be one of the most deadly foes of the Calormenes, dropping them left and right with well-placed shots with her bow. She’s a freakin’ sniper. And – bother it all! – even when it comes to hand-to-hand combat, Aravis in The Horse and His Boy is a trained and competent wielder of a sword.

You know, we might say that the female protagonists in Narnia are pretty bad-ass.

Back to Susan and her no longer being a friend of Narnia. When more details are given about this, it is Jill who disapprovingly says Susan is “interested in nothing now-a-days except nylon and lipstick and invitations.” Notably, another of the women joins in the criticism: It is Polly who adds, “She wasted all her school time wanting to be the age she is now, and she’ll waste all the rest of her life trying to stay that age. Her whole idea is to race on to the silliest time of one’s life as quick as she can and then stop there as long as she can.”

I think many critics have put the wrong emphasis here: They read into it that Lewis is attacking feminine interests — “nylon and lipstick and invitations” — as shallow and frivolous, and they stop there with their assessment, not looking deeper. I think this misses the point entirely. It’s not that Susan cares about those things that Lewis sees as a problem; it’s that those things are all she cares about. She’s obviously reached a “silly age” (which Lewis implies most people go through and grow out of) where she is only concerned about impressions and status and looking just right at the best parties.

And from my reading of contemporary pop culture, I’d say criticizing this type of shallowness is in no way controversial. It is done all the time – I’ll guarantee it has been done by many of those who have disparaged Lewis on this point. If you disagree, you’d best swear off ever making another joke about Paris Hilton or the Kardashians – or I’ll call you out for hypocrisy.

This is actually a hobby horse of Lewis’s, the rejection of wonder (as here represented by Narnia) for mundane and empty pursuits. What he most cares about here is NOT a gender-specific criticism. He could’ve just as easily had one of the boys be “no longer a friend of Narnia,” and one of the other characters would’ve quipped some other shorthand equivalent of lipsticks and invitations (“suits and ties and board meetings”?).

So I don’t believe the absence of Susan is somehow a sexist move. But, yeah, I wish she was there. I would have preferred for all of them to return. It really leaves a final, lingering bummer on a book full of bummers. Not really an issue for me, but this is a book for children. And now that I’m reading it to my daughter, I wish Susan was there for her sake.

As others have pointed out, it is a near certainty that Susan did not die in the train accident – recall she was elsewhere and not involved in what was going on – and there is no reason to assume that she remained for the rest of her life trapped in a shallow stage of wanting to look pretty for the right people in the right circles. She had a whole other story ahead of her. We just aren’t privy to it (although, like Gaiman, we can imagine it).

So there you have it, my final thoughts on the battles that are waged over The Last Battle. While I have defended it at points, it is without doubt my least favorite of the seven for reasons enumerated here. What do you think?

Appreciated your thoughts on Lewis and the insights on Tolkien to boot. My 10th grade English teacher introduced me to Lewis by reading Screwtape Proposes a Toast. I admired him (the teacher) so much and went out and bought The Screwtape Letters-and completely failed to understand it. I also remember it leaving a very depressed dry taste in the mouth so to speak. I may add at this time I had exhausted Edgar Rice Burroughs by way of Ace and Ballentine editions and was gloriously devouring Doc Savage reprints as fast as Bantam released (in fairness the formula finally burned me out and they became less enjoyable later around The Dagger in the Sky reprint. At about this time I discovered The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbitt–read horribly out of order based on what I could find first. This was my reading background at the time.

Jump ahead about three years and I become a Christian (after afew years settled down with liberal Calvinist Baptist leanings-the toleration levels got better as youthful arrogance became replaced with experience and personal events teaching much needed humility. I went back to try Lewis again and THIS time Screwtape made all kinds of sense. Read some more of Lewis’ doctrinal books and was reasonably impressed and finally got around to Narnia.

Sigh. I made it through the first two books and let it go. Tolkien had spoiled me and Lewis himself. I found Narnia as a land to be in comparison with Middle Earth ver undeveloped and the children came off as something out of a Tom Swift novel-never believed they were real. Reminded me of Baum’s later Oz novels where to my mind they became lok and see wonder guides rather then a adventure to be dazzled by. There is probably a reason most people only think Wizard of Oz was the only book though I sort of blame the movie for that perception.

I was aware Narnia was wrapped up but until today did NOT know about the fate of the children let alone Susan. I do think your idea about her is probably what Lewis had in mind. Or to put in more Christian concepts-the love of the world took her away as Demas (New Testament) is spoken of well then later let his path I can relate so very well to this sad to say.

Any way very much appreciate the insights. A bit older now perhaps I should give it another try.

Allard,

Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

I’ve only read the first Oz book myself, which I feel is a real oversight.

Tolkien was just as disappointed in the lack of consistent world-building, the slap-dash, throw-in-everything approach Lewis took with Narnia.

Let me know what you think if you tackle the Narnia books again!

Nice piece!

A word about Lewis’s combining of elements of Greek mythology, Northern European folklore (dwarfs etc.), Christian folklore(Father Christmas), etc. Tolkien objected to this, but Tolkien’s literary tastes tended to stop short of Lewis’s.

Lewis was a great admirer of Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene throughout his life; and if you like Narnia, you should like The Faerie Queene, if you can adjust to the Elizabethan English. Spenser does the same thing — I suppose it’s from Spenser that Lewis got the method. Get hold of Lewis’s Essays on Medieval and Renaissance Literature and read the material on Spenser, and think how so much of what he says is relevant to Narnia. But it’s true that Spenser deals with adult emotions — pride, eros, etc. — so it’s as if the Narnian books could be used as a preparation for youngsters who will later get their chance at Spenser. The book Fierce Wars and Faithful Loves gives Book I of the FQ with a lot of reader-friendly notes.

Nice read. Funny you should mention Madeleine L’Engle. “A Wrinkle in Time” was my own gateway drug at the ripe old age of 13. I had read stuff before that, red fern grows, Grimm’s fairy tales, etc., but this was the one that had me looking for more.

I was pretty much an atheist from a very early age. I think it’s significant that I read ‘The Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe’ and – while recognising the resurrection motif – wasn’t remotely bothered by it. I actually thought it was a pretty cool idea. Authors tend to draw from a variety of different mythologies, but I’d never come across the story that casually appropriated the gospels. As a kid, I thought Lewis was an atheist like me, and had done so to be provocative – which I guess, just goes to show how many different (and how wrong) interpretations there can be of a particular book.

Re-reading it as an adult, what struck me is how much Aslan takes charge and how this undermines the children’s opportunity to make a significant contribution. I wonder if this is – unconsciously – why people have issues about it when they re-read the LWW? Typically, a children’s book (e.g. the hobbit) is all about the character being outside their comfort zone and discovering their own potential. By extension, this is about the transition from childhood to adulthood. But Edmund doesn’t escape from the White Witch – he’s rescued, at Aslan’s instigation. Nor do Susan and Lucy rescue Aslan: they’re relegated to the role of passive witnesses. The book stops being the children’s story and becomes Aslan’s story. Lewis’s faith often works to the benefit of his books, but in this respect I think it works against the story’s natural direction – ie, there’s no reason why you couldn’t keep the resurrection theme and still have the children being more proactive.

As regards ‘The Last Battle’, I actually think it works: ‘Inner Narnia’ wouldn’t be so effective if ‘Outer Narnia’ didn’t seem so grim by comparison: it’s like the light at the end of a particularly dark tunnel, and only somebody who genuinely believed in an afterlife could present it so convincingly. On the charges of racism – unfortunately I think that charge could be levelled at pretty much most writers in the first half of the twentieth century (anti-semitism is pretty much ubiquitous, for example) so I’ll give Lewis a pass on that. The Susan thing never bothered me much, but then I’m a guy? I think any happy ending has to be qualified to some degree, if only to be credible. *Somebody* has to lose out.

Just my (lengthy) two cents’ worth.

Aonghus Fallon, your comment about the (so brief!) “Susan note” at the end of The Last Battle reminded me of Shakespeare!

Remember Twelfth Night? At the end, everybody’s matched up with an appropriate mate and there’s a delightful feeling of harmony restored — BUT Shakespeare isn’t content to leave it at that. The pain-in-the-neck Malvolio, who’s been subjected to a humiliating series of practical jokes, vows that he will be avenged. he stalks off the stage. It’s a brief moment, but it qualifies the general merriment. Isn’t that a similar masterstroke?

Anyway, thanks, Aonghus, for your comment, which prompted a thought about TLB that I’ve never had before despite several readings.

I wonder if some of the reason some folks have a problem with The Last Battle in particular is because that’s the book where it pulls the mask off the allegory like Old Farmer Jenkins at the end of a Scooby-Doo episode.

And now I kind of want to see an article comparing The Last Battle to Moorcock’s Stormbringer, both series-ending novels in which we see the world slowly being literally deconstructed.

I grew up reading the Chronicles of Narnia over and over again, and I have to say that I found The Last Battle terrifying. Its vision of eternity as a serial infinity, a geometric progression of concentric worlds, froze my blood. It literally made me want to be an atheist, although that terrified me, too. I mean, forever is a long time, whether you’re annihilated or your timeline is indefinitely prolonged. What if you lived forever, but you got…bored? Wouldn’t you get bored eventually? Maybe each Narnia is bigger and better than the last, but wouldn’t you eventually get bored of the way in which they increase in splendor? Wouldn’t you eventually get bored of a talking lion’s company? What then? The doom of Tithonus. The horror of the infinite. I remember sitting up late at night thinking about it. Like a character in a Borges story, I wanted to burn the book, but I feared to, lest its smoke smother the world. I guess I was kind of a high-strung kid.

“It wasn’t the Christianity he [Tolkien] had a problem with.” It has always struck me that Tolkien did have a problem with Lewis’s religious views, and that this is one of the things that led to their eventual rift. It just wasn’t Christian vs. non-Christian. It was Catholic vs. Anglican. Tolkien objects rather sharply to Lewis’s anti-Catholicism in some of his letters, and seems to me to have found Lewis a bit glib on religious matters. Personally, I suspect that Tolkien objected to the Narnia books on those grounds as well as others.

That’s a great analogy, M.W. I’ve seen ‘Twelfth Night’ a couple of times – I actually really like Shakespeare’s comedies – but I’d totally forgotten that final scene with Malvolio.

I think Shakespeare knew what he was doing, though. No happy ending should be too pat, and if you look at ‘The Last Battle’ from the perspective that *one* of the four has to lose out, and consider which one of the four it could be – who would you choose?

Major Wootton,

Yes, I recall that Spenser’s The Faerie Queene was one of Lewis’s major literary influences, although I have never gotten up the gumption to read it (it is a daunting book!)

If I also recall correctly, Tolkien disliked The Faerie Queene; it, too, being too allegorical for his tastes.

CMR,

A Wrinkle in Time is in the queue for bedtime readings to my daughter, although I think we’re going to move on to Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising next (an acclaimed young-adult fantasy series I never have gotten around to reading).

Aonghus Fallon,

You do raise another criticism worth considering: the question of Aslan’s powerful (some would say intrusive) role throughout the series as Deus Ex Machina.

Since that means “God in the Machine,” here it is particularly apt, as Aslan is, according to Lewis’s own worldview, God Incarnate (part of the Trinity; “Son of the Emperor Over the Sea” as Jesus is “the Son of God the Father”).

There are passages that are quite illustrative of Aslan directly manipulating events, such as when His face appears in the Magician’s Book to scare Lucy off from casting a particularly dangerous spell, or when He appears at key locations along the road in The Horse and His Boy to frighten the protagonists into meeting each other and then staying on the right trail.

To some extent this interaction feels part-and-parcel with Narnia because in the cosmology of that world its Creator does take a direct role in individual lives, not to override Free Will but to provide helpful nudges to those who are loyal to Him.

It reflects Lewis’s own worldview. There is an evangelical tract that gets handed out by Christian witnesses on high school and college campuses that begins, “God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life.” (It has become such a common refrain that if you look it up on Google you will get nearly 4 million hits.) Lewis believed this. He believed that God occasionally intervened in his own life, to steer him onto one path or another, just as Aslan does for the children in Narnia.

Of course, not all readers believe that; but, as you pointed out, it can still be read with a suspension of disbelief as we read any mythology that has gods and divine beings interacting with humanity. We’ve accepted, for the sake of the story, that animals in Narnia can talk; so one of them also happens to be the Creator.

On the other hand, it drives some people (like Philip Pullman, author of the “anti-Narnia” books His Dark Materials) apoplectic!

I also wanted to respond to this point: “As regards ‘The Last Battle’, I actually think it works: ‘Inner Narnia’ wouldn’t be so effective if ‘Outer Narnia’ didn’t seem so grim by comparison: it’s like the light at the end of a particularly dark tunnel, and only somebody who genuinely believed in an afterlife could present it so convincingly.”

I do agree with you here. Having just re-read the ending, I found it quite powerful, despite some misgivings about the mechanics of it (which I address in my next response to Raphael). My daughter and I both got excited (she clapped; I got a little choked up) when beloved characters from earlier in the series re-appeared. And I was reminded that Lewis was a neoplatonist at heart (a philosophical worldview that is not incompatible with Christianity). In the final pages of The Last Battle, in fact, Lewis gives a crash course in Platonic Forms. All the things around us are but shadows of the Ideal Forms, and the characters leave this Shadow-Land to enter the world where everything is more real.

Lewis also gives a nod to a philosophical view that I think he first learned from Tolkien. Tolkien expresses it in his own allegorical story “Leaf by Niggle”: that what we do or make in this world can shape the transcendental world. In Tolkien’s story, Niggle has a picture in his head of a beautiful forest; he works painstakingly at a painting but all he ever produces in his lifetime is a wonderfully deep, rich, vibrant painting of a leaf. When Niggle dies, he finds himself in the Afterlife in the forest he imagined, the image perfected. This idea (call it wish fulfillment — if so, it is a wish that I dearly wish) is that the best things, the most beautiful things can be “taken up” and shape Reality beyond the nature of the flatland world in which we live. They transcend the finite and exist in the Eternity outside time. Lewis suggests this when he has the children notice Professor Kirke’s old house — there in the London Beyond London, existing in perfection because it was good, even though its shadow-land antecedent was torn down. What a glorious idea!

Aonghus Fallon and Major Wootton,

I had the pleasure of understudying for a production of Twelfth Night fifteen years ago. The actor who played Malvolio was one of the finest I have ever worked with. His delivery of that final monologue was so gut-wrenchingly heartfelt that it felt like a minor tragedy when he walked off stage — one felt so sorry for the character. Ass though he was, he really could with justification protest, “You have done me wrong. Notorious wrong!”

Raphael,

Oh my goodness, you have hit on an interesting topic! I recall being somewhat disquieted by that myself as a young reader. It seemed wondrous — “Further up and further in!” Each higher stage more beautiful and awe-inspiring than the last. But yeah, there was that little voice, too, whispering in the back of my head, “But then, what, they just keep on going ‘further up and further in’ forever? Do they ever get somewhere? A final destination? Or is it one more perfect world after another, like nesting-dolls-to-the-infinite-power?

Really, such questions arise whenever one begins to deconstruct simple notions of Heaven. “We meet all our lost loved ones? Okay, and after the reunion, then what? Go meet all the people we ever wanted to meet — hey, go and meet EVERYONE, one on one; that’ll maybe consume several thousand years. Then what?” Or “We get to sing praises to God for eternity? Like, when we sing out of the hymnal at Sunday service, but this goes on for ever?”

Of course, Christians of a more philosophical bent have long realized that such notions are simple-minded and silly. Eternity, most Christian thinkers recognize, is not time dragging on forever, but an absence of time altogether — it is outside time. In their conception of Heaven, one is freed from the bondage of flat, linear, finite time, rising above it to exist in the eternal Now, perhaps much like God. Which is very hard for us to imagine, except maybe in rare moments of enlightenment, like the mystics and sages.

That’s really interesting, Nick. I know there was an earlier, unfinished draft of LWW which didn’t feature Aslan at all. Maybe Lewis turned to his faith for inspiration – or (properly speaking) an answer.

Nick, a wonderful article, I very much enjoyed it. It reminded me of some issues I haven’t thought of in some time. I have to add that your assessment of Susan’s situation pretty much matches what I’ve always thought.

Major Wootton, I can’t find the name of it, but Lewis also wrote a book about Paradise Lost that I read for my minor comprehensive exams. I found it very useful, and quite interesting in itself.

Aonghus, I once wrote a paper comparing The Hobbit and the Chronicles of Narnia, and came to much the same conclusion as you do here.

Aonghus Fallon,

Yes, like the germination of so much of his fiction, Lewis said that LWW started with a picture: a faun standing under a lamppost in winter holding a bundle of Christmas parcels. What story, he wondered, would go along with that?

But the second, integral ingredient came to him in a dream: Aslan emerged from a series of recurring nightmares of a terrifying lion, who became Aslan and pulled it all together.

Violette Malan,

Thank you! The title of the Lewis book you’re thinking about is A Preface to Paradise Lost.

Very nice thoughts. Thanks. I have some thoughts as well.

On the racism issue, the darker skin and Calormene culture go together. If you have a dark person, they are also pagan in a particular way. So the color is a marker for the culture in this case. And Lewis doesn’t seem to worry about color if the Calormene characters are good and honorable people. So I think perhaps there is mistaking culture markers for racism. I think people try to twist everything into a racist perspective as a current social fad, when much of what happens is just the way life goes, and not a product of skin color.

My other thought is about how dark The Last Battle is. Everybody dies at the end is pretty dark. You ask if this is appropriate for children. I think it is. The world isn’t a nice place in some respects, and bringing that to a children’s series helps them begin to transition to adulthood. Even though everybody dies, and Narnia ends, the characters effectively go to heaven and we don’t know the real disposition of the evil characters in the story. Kids have to begin the transition somewhere, and to me, this is as good a spot as any to do that.

Lastly, the issue of Susan isn’t a problem for me. People fall away from truth. It happens. I think Lewis wanted to make sure we understood that by our own choices, not everyone comes to a happy ending. It therefore behooves the children who get to have these stories to make choices that provide good results and hold on to the faith.

I’m really disappointed in most of your criticism. Instead of pointing to actual literary problems, you insist the book is offensive because Lewis is allowed to express his religion, because real life cultural differences are portrayed, and because a female character behaves in a way that real women behave. Sometimes people behave in a shallow manner, and it’s not because Lewis hated women that Susan was not a part of the book. He even mentioned that he had plans for her. But you have to remember that the Last Battle was published in 1956, and, after struggling with illness, Lewis died in 1963. He never got to complete his intentions.