Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar Saga: Tanar of Pellucidar

A long time has passed, both on the surface of the Earth’s sphere and within it. On the surface, it’s been almost fifteen years since Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote the second of his inner world adventures, Pellucidar. During this time, ERB penned another ten Tarzan novels, a couple more Martian ones, and a few of his finest standalone tales. Burroughs incorporated himself and set up the offices of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. in a part of the San Fernando Valley soon to be named Tarzana. It seemed unlikely he would return to writing about Pellucidar after almost a decade and a half … but then he hatched a plan to give the Tarzan series a boost using the fuel of the Earth’s Core.

A long time has passed, both on the surface of the Earth’s sphere and within it. On the surface, it’s been almost fifteen years since Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote the second of his inner world adventures, Pellucidar. During this time, ERB penned another ten Tarzan novels, a couple more Martian ones, and a few of his finest standalone tales. Burroughs incorporated himself and set up the offices of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. in a part of the San Fernando Valley soon to be named Tarzana. It seemed unlikely he would return to writing about Pellucidar after almost a decade and a half … but then he hatched a plan to give the Tarzan series a boost using the fuel of the Earth’s Core.

Our Saga: Beneath our feet lies a realm beyond the most vivid daydreams of the fantastic … Pellucidar. A subterranean world formed along the concave curve inside the earth’s crust, surrounding an eternally stationary sun that eliminates the concept of time. A land of savage humanoids, fierce beasts, and reptilian overlords, Pellucidar is the weird stage for adventurers from the topside layer — including a certain Lord Greystoke. The series consists of six novels, one which crosses over with the Tarzan series, plus a volume of linked novellas, published between 1914 and 1963.

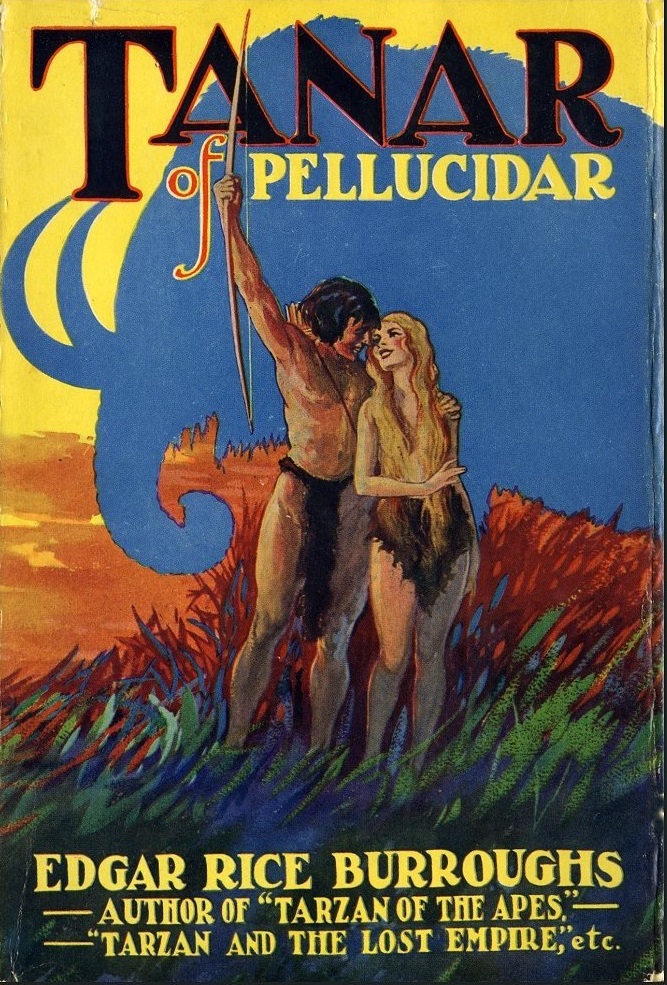

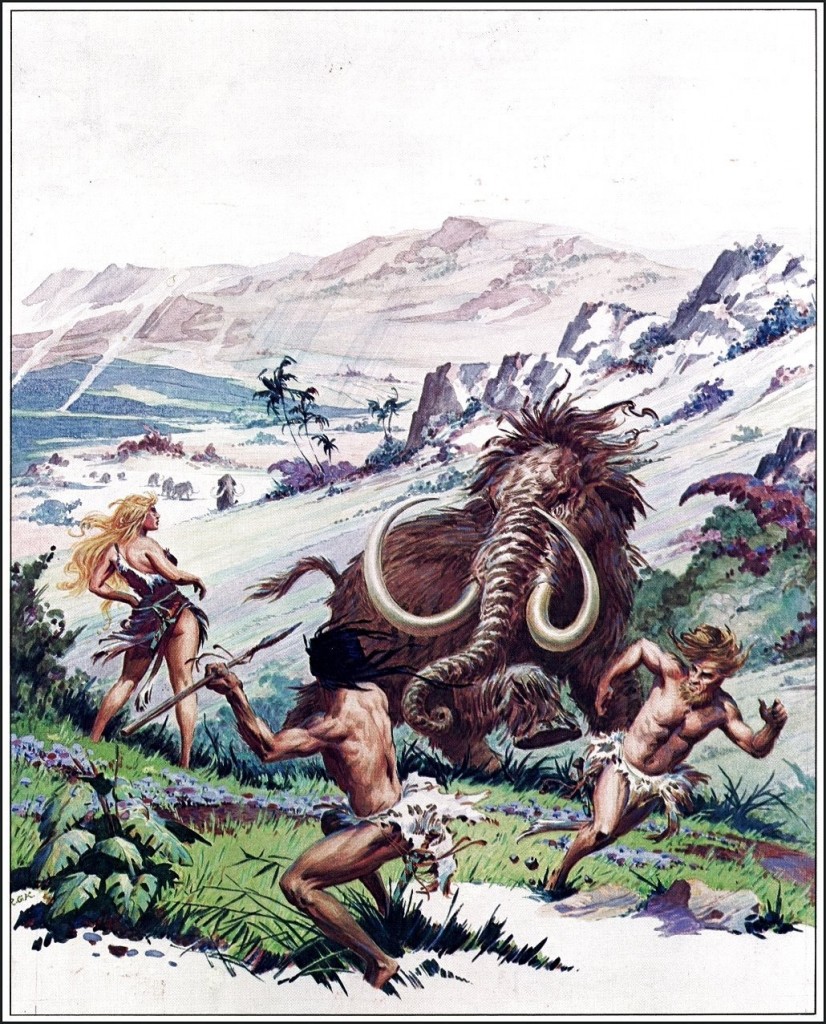

Today’s Installment: Tanar of Pellucidar (1929)

Previous Installments: At the Earth’s Core (1914), Pellucidar (1915)

The Backstory

The gap between Pellucidar and Tanar of Pellucidar is fourteen years, the longest hiatus for any of ERB’s major series. Despite numerous pleas from readers, Burroughs apparently had no intention to explore Pellucidar further. But at the end of the 1920s, he devised a plan to jolt life back into the Tarzan books by sending the Lord of the Apes somewhere stranger than the usual lost jungle cities. He already had that “somewhere stranger” waiting to be used: Pellucidar was the perfect Tarzan destination vacation!

But first, Pellucidar needed a bit of a dusting-off to set it up for Lord Greystoke’s arrival, as well as to remind the reading public that the setting existed. Burroughs put into action a two-book plan, starting with a new standalone Pellucidar novel to lure readers into the upcoming Tarzan adventure.

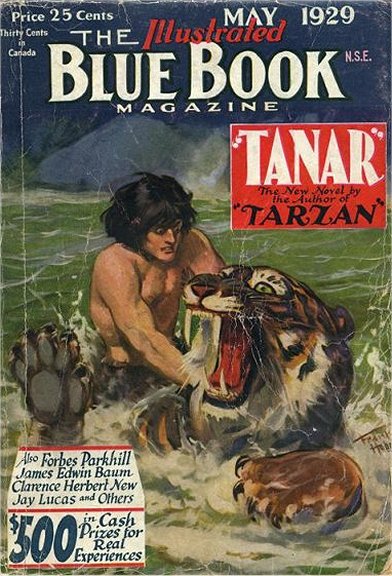

Burroughs completed Tanar of Pellucidar in 1928, and it was published in Blue Book in six installments from March to August of the following year. It led immediately into Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, which started its serial run in the magazine without pause in September.

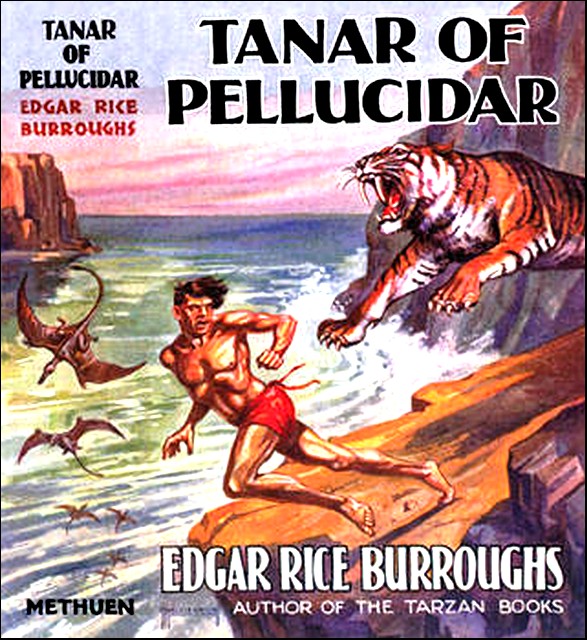

The hardcover of Tanar of Pellucidar came out in 1930, the second ERB book from Metropolitan Services, the company Burroughs moved to after a split with A. C. McClurg. For some reason J. Allen St. John did not supply the cover illustration, although he drew the one for Tarzan at the Earth’s Core. Not sure why that happened.

The Story

The Story

Now living in Tarzana, the fictional version of Edgar Rice Burroughs relaxes with his radio-loving neighbor, Jason Gridley, who thinks all of Ed’s novels are “baloney.” Gridley has discovered a new form of radio communication (don’t ask how it works, neither version of ERB knows) called “The Gridley Wave.” Via this powerful wave, the two receive a transmission from Abner Perry in Pellucidar.

Perry brings grim news: Emperor David Innes is a captive. Sea raiders known as the Korsars armed with gunpowder weapons have assaulted the coastal cities. When the pirates made off with a valuable hostage, the son of Innes’s ally Ghak of Sari, Innes set out with only two companions on a rescue mission.

For the rest of the tale, we shift to the adventures of Tanar, Son of Ghak, who is a prisoner on the ship of the Korsar leader, The Cid. The pirate wants Tanar to teach him the method of making more powerful gunpowder. This becomes moot when a storm wrecks most of the Korsar fleet. The Korsars abandon The Cid’s ship, but Tanar remains behind with Stellara, The Cid’s hot-tempered daughter. Stellara isn’t The Cid’s true daughter, but the descendent of a slave woman brought from the island of Amiocap. (Pacoima backwards, a local neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley.) Tanar and Stellara immediately fall into a love-hate relationship.

The two drift to the shores of Amiocap and start a series of adventures across the islands as Tanar attempts to make it back to Sari and/or rescue Stellara. Tanar finds the underground culture of the inhuman Coripies and then spends time in the village of Garb and its eternal squabbling married couples. After a few kidnappings, fits of jealousy, betrayals by allies, and fights with beasts, the hero and heroine end up back in the clutches of The Cid. The pirate brings them to the city of Korsar, where they find that The Cid has David Innes imprisoned.

Tanar helps Innes escape, and on a flight northward they make the amazing discovery of a giant hole opening at the poles that reaches the outer world. The Korsars recapture Innes, leaving it up to Tanar, Stellara, and their companions to make it back to Abner Perry with news of Innes’s capture.

Of course, we already know they’ll succeed — otherwise Perry wouldn’t be narrating their story over the Gridley Wave. Jason Gridley, now a true believer in Pellucidar, declares that he will seek the polar gateway and rescue David Innes! (Even though we all know Tarzan will actually do it.)

The Positives

The Positives

You can feel the decade and a half gulf between Tanar of Pellucidar and its predecessors: we’re firmly in a different phase of ERB’s career. Tanar is an example of a mid-tier Edgar Rice Burroughs novel; what Richard Lupoff called “the good potboilers.” The plot is messy and characterizations thin, but events still putter along at a good clip and the majority of the action works.

When analyzing what works about an ERB novel, I usually deal with the framing device last. But in Tanar of Pellucidar the frame is the most important part of the novel. Not only does it put the pieces in play for Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, it sets up the central conflict of both books: the captivity of David Innes. The Prologue also introduces an essential piece of the Edgar Rice Burroughs Extended Universe (ERB-EXU), the Gridley Wave. This bit of fuzzy science will come up in many future books since it makes it easier for pseudo-ERB to receive communications from his heroes scattered around Mars, Venus, Pellucidar, etc.

The main joy in the Prologue is the meta-gag of Jason Gridley critiquing ERB’s books by needling the fictional Burroughs about them. He isn’t happy that Ed killed off Hooja the Sly One so facilely in Pellucidar (I agree with Gridley on this) and writes too many damsels in distress fleeing from villains. Pseudo-ERB drops some tidbits about the real Burroughs’s life (he hates camping, his friends call him “Admiral” because he likes to wear a yachting cap at the beach). There’s a tremendous amount going on in these few opening pages.

The best conceptual idea in Tanar is the Coripies, a.k.a. “The Buried Ones.” Similar to the plant men in The Gods of Mars, the Coripies are grotesquely alien, and Burroughs uses graphic prose to describe their uncanny eyeless physiognomy. The book’s most exciting section is Tanar’s sojourn in the Coripi underground. Their chieftain Xax imprisons Tanar in his larder along with Coripi offenders whom the rest of the tribe plan to eat eventually. These flourishes of horror with a bizarre new race are exactly what a Pellucidar book should include, and they play to Burroughs’s talents.

Tanar’s first encounter with a Coripi results in a fantastic extended fight, one of a number of excellent action passages. Even with the haphazard plotting, ERB still knew how to stage a blood-rushing life-or-death tussle. Tanar also gets into a tense underwater struggle with a tarag (sabertooth cat) and a sickening encounter with a wave of snakes inside the dungeons of Korsar. Although the book’s climax arrives two chapters after the natural end of the story, the ocean chase between The Cid’s fleet and Tanar and Stellara in a sailboat is a corker, concluding with Tanar making a suicidal rush at the coast.

Speaking of what should have been the actual climax … The discovery of the exit from Pellucidar to the surface world is an awe-inspiring moment. The travelers at first notice their shadows are no longer directly under them, and then see what seems to be a second sun floating on the … wait, I’ll let Ed tell you:

The others stood in silent awe, watching the edge of a blood red disc that seemed to be floating upon a gray ocean across whose reddened surface a brilliant pathway of red and gold led from the shoreline to the blazing orb, where the sea and sky seemed to meet.

At this point, I’m pumped for Tarzan to swing through this gap in the world and come to the rescue!

The Korsars are a good lateral solution to a problem Burroughs left himself at the conclusion of Pellucidar when he erased the Stone Age technology of the setting and reduced the Mahars as a major threat. Although there was more juice to squeeze from the Mahars, switching to a new overall adversary was a perceptive decision. The Korsars never dominate the action the way the Mahars did, but using Spanish Main pirates with crude gunpowder weapons and advanced sailing ships changes how events unfold. The Korsars have enough technology to provide a different threat without simply wiping our Pellucidar’s Industrial Age advances. Besides, pirates are fun, and the Korsars’ origin from the surface world three hundred years in the past broadens the possibilities of Pellucidar.

The Korsars are a good lateral solution to a problem Burroughs left himself at the conclusion of Pellucidar when he erased the Stone Age technology of the setting and reduced the Mahars as a major threat. Although there was more juice to squeeze from the Mahars, switching to a new overall adversary was a perceptive decision. The Korsars never dominate the action the way the Mahars did, but using Spanish Main pirates with crude gunpowder weapons and advanced sailing ships changes how events unfold. The Korsars have enough technology to provide a different threat without simply wiping our Pellucidar’s Industrial Age advances. Besides, pirates are fun, and the Korsars’ origin from the surface world three hundred years in the past broadens the possibilities of Pellucidar.

Tanar’s visit to the village of Garb, a place of non-stop domestic chaos, is a detour that doesn’t really belong, but it’s funny for the sheer outrageousness of what feels like Leave It to Beaver reimagined for the post-apocalypse. Married life in Garb is a constant war of marital dissatisfaction, quarreling, and cheating on both sides. Garb also gifts us with the book’s most memorable line, the matter-of-fact statement: “She is his sister, he has a right to hurl rocks at her if he chooses.” That there is really all you need to know about Garb.

The lasting impact from Garb is the book’s most interesting female character, the lovelorn Gunar. Stellara is an adequate heroine, but Gunar’s wish to escape from the grayness of her village and her quiet, unrequited love for Tanar give her an element of tragedy. In the coda, she’s left with a bittersweet finale that’s quite touching.

There are only a few satirical touches outside of Garb, but Burroughs manages one or two stingers, such as Tanar’s observations on civilization:

“Yet he [Abner Perry] and David, our Emperor, have brought us many advantages that were before unknown in Pellucidar, so that now we can kill more warriors in a single battle than was possible before during the course of a whole war. Perry calls this civilization and it is indeed a very wonderful thing.”

Burroughs apparently recognized that having David Innes figure out a way to tell time in Pellucidar at the end of the previous book undercut one the best aspects of the setting. He undoes it with the conceit that the Pellucidarians simply didn’t like the idea of time, and David Innes issued an edict that abolished it. Problem solved, and Pellucidar is the better for it.

We learn a few new facts about the timelessness of the inner world, such as how the inhabitants have biologically adapted to it. People are capable of “storing sleep” so they can remain awake for long stretches when necessary, meaning sleep patterns are on an “at need” basis. Like the nature of time in Pellucidar, this makes no scientific sense, but it’s a solid idea for the surreal world at the Earth’s core.

The cliffhanger coda works since it doesn’t conclude with Tanar — his story has already wrapped up — but with Jason Gridley. David Innes is trapped in a Korsar prison, and in the book’s final sentence, Gridley declares that he’ll take on the rescue mission. Despite its faults, Tanar of Pellucidar makes readers want to dash to pick up the next book … especially since they know that it isn’t Gridley who’ll make the great adventure — it’s Tarzan.

The Negatives

The late 1920s was a period when Burroughs’s writing started to lose focus, making its flaws more noticeable. Although a few years away from the nadir of the late 1930s (see: Synthetic Men of Mars), the future troubles were already evident. The Master of Adventure was still capable of good work in the late ‘20s — the superb A Fighting Man of Mars was written at this time — but the majority of his output was more akin to Tanar of Pellucidar: entertaining but baggy and clumsily cobbled together, with fewer interesting characters and some who barely stick around long enough to capitalize on their potential.

The titular hero does the most overall harm to the book. Changing the series protagonist from David Innes to a native of Pellucidar was a good idea on the surface. But Tanar is bland and immediately makes me wish we were still viewing events through Innes’s outer world POV. Nothing about Tanar of Sari is remarkable. He has no special skills, no unusual goals, no great dreams, no outsider status. For most of the story he just wants to go home to his father’s kingdom, and he’s not terribly passionate about it. He seems content to simply wander the islands.

The titular hero does the most overall harm to the book. Changing the series protagonist from David Innes to a native of Pellucidar was a good idea on the surface. But Tanar is bland and immediately makes me wish we were still viewing events through Innes’s outer world POV. Nothing about Tanar of Sari is remarkable. He has no special skills, no unusual goals, no great dreams, no outsider status. For most of the story he just wants to go home to his father’s kingdom, and he’s not terribly passionate about it. He seems content to simply wander the islands.

Even Stellara doesn’t infuse much energy or motivation into Tanar. Stellara isn’t a bad character; she’s a more active and interesting female lead than Dian in the first two books. But because Tanar shows no special passion for her that isn’t Pulp Hero mandated, it’s obvious that she exists only to move events geographically every couple chapters.

Because Tanar isn’t engaging, the wobbly set of adventures he goes on feels even wobblier. The plot flits from place to place and turn to turn rapidly, so much so that it can be tough keeping up. The plot sketch I originally wrote to work from for this article was 1300 words long, and that with as much condensing as I could manage. But all this action is an illusion, because there’s actually little forward momentum toward a goal during the island-hopping. The story needs to reach the city of Korsar, and until that point most of what happens is time-killing, even the interesting stretches like the Coripies and the comedy stint at Garb. The aim is to reach David Innes, which readers already know from the Prologue and Introduction. But Tanar and Company don’t know this and instead go on an island tour and do the escape-kidnap-chase routine a few times until The Cid catches them and drags them to the city of Korsar where Innes is imprisoned. Nothing the heroes do on their own guides them toward the finale.

Events need to ramp up rapidly after reaching Korsar, but the big escape sequence from the city is dull compared to the earlier action. It’s an almost pointless escape as well, because David Innes and Tanar end up captured again and Tanar has to do the escape a second time on his own. The only achievement of the first escape is discovering the polar entrance to Pellucidar. That amazing moment should’ve shot right into the final chase, with Innes recaptured but Tanar and Stellara managing to elude the Korsars on the sea. Instead, the action resets in Korsar for a few more chapters before a second escape. It’s a strange pacing mistake for Burroughs to make.

(There’s one upside to this delaying section, which is that Tanar befriends a snake while entombed in the dungeons. It’s a cute variation on the old-fashioned animal sidekick. David Innes gets a prehistoric wolfhound, Tanar gets a snake.)

Most characters disappear soon after their introductions, which further makes the story shaky. The Cid’s first mate, Bohar the Bloody, appears in Chapter One as a major adversary who plans to marry Stellara. But at the middle of the story, after Bohar has been out of the action for a few chapters, the pirate re-emerges just in time for Tanar to slay him. Bohar is then replaced with an essentially identical character, a Korsar named Bulf who also plans to seize Stellara. Bohar/Bulf is functionally the same role, and having one take over from the other deprives readers of getting a sense of menace from either.

The characters who suffer the most from story haste are Mow, a sympathetic Coripi, and Jude, a man from the village of Carn. Both show immense promise as unique characterizations, but then vanish before much happens. Mow is a captive among his own people whom Tanar befriends. There’s potential here for examining the Coripies in a different light — possibly even putting Mow into a secondary hero role. But Mow only stays around long enough to help Tanar and Jude escape the underground pit, and then he vanishes for good — as do the Coripies and all the benefits they offer the story.

The characters who suffer the most from story haste are Mow, a sympathetic Coripi, and Jude, a man from the village of Carn. Both show immense promise as unique characterizations, but then vanish before much happens. Mow is a captive among his own people whom Tanar befriends. There’s potential here for examining the Coripies in a different light — possibly even putting Mow into a secondary hero role. But Mow only stays around long enough to help Tanar and Jude escape the underground pit, and then he vanishes for good — as do the Coripies and all the benefits they offer the story.

Jude, a man obsessed with living in unhappiness and the source of a few funny bits of dialogue, doesn’t last much longer. In an out-of-character moment after the escape from the underground, Jude betrays Tanar and kidnaps Stellara. This is done just to shift the action from Amiocap to the Island of Hime. But when the Korsars re-enter the action, Jude retreats into a cave and — poof! — he’s out of the story for good as well. (And Jude’s most villainous act, slipping into his village to murder his mate so he’s free to marry Stellara, is left implied. I would’ve liked to see that!) ERB could’ve significantly strengthened the book’s middle stretch if he granted more time and attention to both Jude and Mow.

It feels redundant to complain that the romance between Stellara and Tanar consists of placing petty obstacles between them, such as Stellara developing an unrealistic jealousy after a single glance of Tanar walking in the distance with another woman. This is how romances tend to operate in Burroughs’s novels, even many of his best. My specific gripe here is that the romantic obstacles are unnecessary. There’s no need to have Tanar and Stellara personally at odds beyond the early sections; they actually come to a resolution at right around the middle of the book. But random jealousies flare up again, despite not adding real story complications. The hero and heroine then simply shrug off their conflicts in the final chapters because the story requires it.

I suppose it’s also redundant to bring up the outrageous coincidences that sometimes shove events along. But I’m going to do it anyway. There are at least three major moments of characters wandering the wilds or getting shipwrecked at the right point to run into the exact people they need to meet. Yes, Burroughs did this in other novels where it wasn’t much of a bother, but this is another example of how a book’s flaws become more noticeable when the story and characters aren’t well assembled.

Establishing city-states or nations that have opposing world views is a common ERB device. Here the conflicting cultures are the villages of Lar and Garb. Lar is presented as a society of love that enjoys immense happiness and perfection in almost everything. (Burroughs claims the whole island of Amiocap is the Island of Love, but this doesn’t make sense when the first village that Tanar and Stellara come to orders them to be burnt alive.) Garb is a place of hate, an ongoing domestic feud where marriage is meant to be misery for both men and women.

The Lar/Garb comparison feels like the author making an observation about the extremes of marital contentment, but neither location has much to do with the rest of the story or has any affect on Tanar or Stellara. And if these locations are meant as satire, neither connects. Garb is briefly amusing and does provide the rest of the novel with the character of Gunar. Lar, however, goes nowhere and provides nothing. After Letari, a young woman of Lar, surrenders her claim on Tanar, the village setting is finished. This type of underdeveloped concept would increasingly plague Burroughs’s work through the 1930s.

For a band of pirates with more than three hundred years of history, the Korsars are rotten sailors. They shipwreck twice in the space of two adjacent islands! At least they know how to construct boats fast; they must go through a lot of them.

No J. Allen St. John cover? That feels wrong. But I’m a huge St. John fan, so this is just me.

Craziest Bit of Burroughsian Writing: Jude on his unfortunate view of life. “I enjoy being unhappy. I know that I should be most miserable were I happy and anyway I should much rather be alive and unhappy than dead and unable to know that I was unhappy.”

Most Inventive Idea: The culture and physiognomy of the Coripies

Best Creature: The codon, a super-timber wolf

Carson Napier Pre-Memorial Foolishness Award: Tanar, armed only with a spear, confronts a dozen Korsar pirates carrying loaded pistols and arquebuses. Fortunately for him, he trips and falls down a pit before the pirate fusillade perforates him.

Timelessness Backfires: When a bull (thag) has you trapped up in a tree, it’s hard to wait him out when time is meaningless.

How about a sequel? Ed already wrote it. Starting next month, in the pages of this very magazine, Tarzan to the rescue!

Next: Tarzan at the Earth’s Core

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Interesting — I hadn’t noticed that there was such a gap between Pellucidar and Tanar.

And for a while, back when such things mattered to me, the whole Pellucidar/Tarzan crossover thing drove me crazy in terms of reading — do I read the first dozen Tarzan novels, then switch over to Pellucidar? And what do I continue with after Tarzan at the Earth’s Core? It really was a dilemma …

@Joe – A dilemma I understand. I remember facing it back in the early days (high school) when I reached Tarzan at the Earth’s Core in the Pellucidar series long before reaching the same point in the Tarzan series. Of course I did: it’s the 14th Tarzan book but only the 4th Pellucidar book! I went ahead with Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, realizing I was violating some great chronology. Then when I read the rest of the Tarzan series and found out that by that point ERB was very much in episodic Tarzan mode I realized I made the right choice (by accident). But if you love ERB, this sort of debate is gonna come up.

Fighting Man of Mars always felt like someone else wrote it. It didn’t really feel like Barsoom to me. It literally looked differant in my head ( I’m an artist). The colors were wrong, It was flat somehow. It was as though the characters were experianceing a differant world than those in the previous books. As excited as I was to read Barsoomian point of view it just didn’t work for me and still don’t really know why.

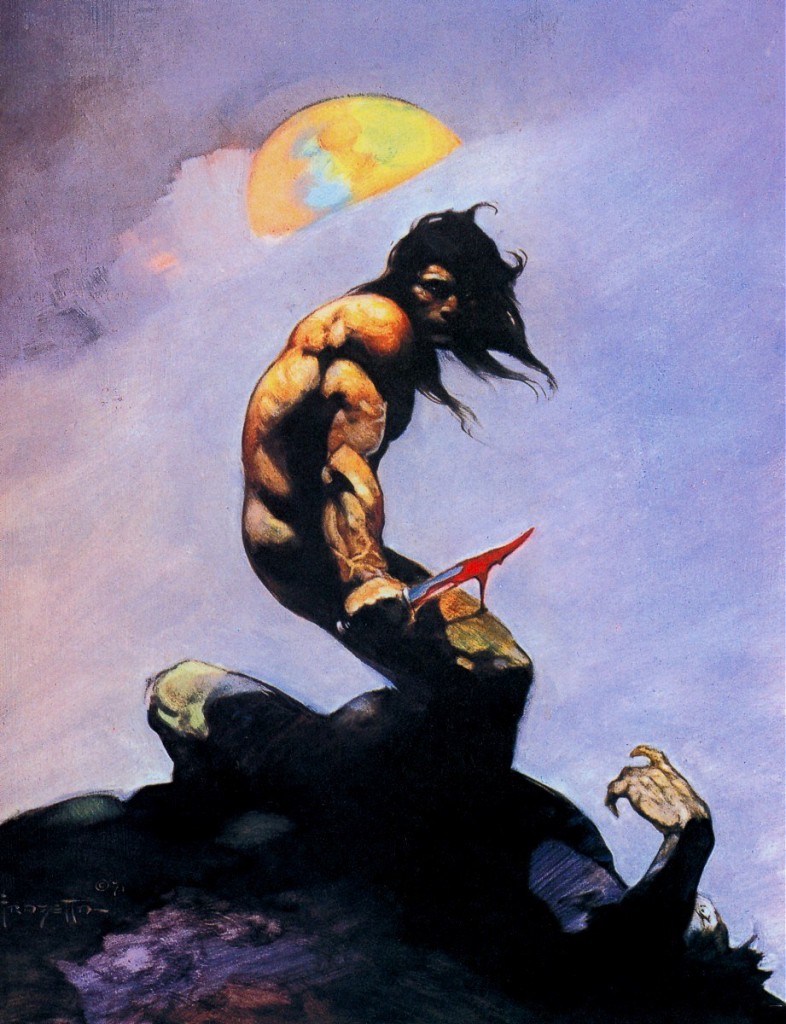

Excellent post as usual, Ryan. “Tanar” may be a little thin, but it still has a place in my heart. That Frazetta cover is incredible. Better than some of his Conan work.

ERB should’ve done a little more with the Korsars, IMO. Hell, some evil, Odin-worshipping, blood-eagling, human-sacrificing Vikings would’ve been fine with me.

As it is, this and the next two is the “Pellucidar Trilogy” we got.

@Deuce – The disappointment with the Korsars only really sets in for me in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, where you expect a major confrontation with them—and then it doesn’t happen. But I have to hold back now because that’s for next time.

Yeah this was a meh one for me. The prologue was fun, the opening chapters with David Innes but Tanar and Stellara were boring.