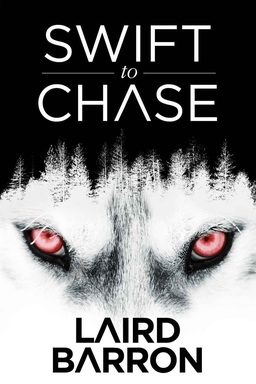

Making Lovecraft Look Quaint: Swift to Chase by Laird Barron

Laird Barron is, to my mind, head-and-shoulders above any other horror writer around today. Besides being terrifying, his stories exhibit a real gift for expressing the existential angst of classic cosmic horror, that genre that was perfected so well by the late H. P. Lovecraft. But Barron has so excelled in crafting this sort of tale that calling him Lovecraftian is seemingly rather quaint. For Barron knows how to uniquely weave together seemingly disparate strands in very original ways that bring the horror reader to that wonderful seesaw state of being overwhelmed by the horrific, while also finding aesthetic joy in it.

Laird Barron is, to my mind, head-and-shoulders above any other horror writer around today. Besides being terrifying, his stories exhibit a real gift for expressing the existential angst of classic cosmic horror, that genre that was perfected so well by the late H. P. Lovecraft. But Barron has so excelled in crafting this sort of tale that calling him Lovecraftian is seemingly rather quaint. For Barron knows how to uniquely weave together seemingly disparate strands in very original ways that bring the horror reader to that wonderful seesaw state of being overwhelmed by the horrific, while also finding aesthetic joy in it.

Swift to Chase is Barron’s fourth collection and is often called, by the author himself, his Alaska book. Barron originally hails from the 49th state, and many of his past stories take place in the American northwest, especially the state of Washington. Though this new book focuses upon Alaska, in many ways this real-life setting strongly echoes elements in Barron’s prior collections.

Many (if not all) of Barron’s stories appear to take place in the same sandbox, the same fictional universe. Barron, like the late Lovecraft, often includes recurring regions, locations, and characters in many of his stories. Those familiar with Barron’s previous stories will notice many familiar hints in Swift to Chase. But this is the first Barron collection where there is a definite theme throughout the stories (with perhaps one exception). What is this theme? Besides focusing upon Alaska as a setting, many of these stories hearken to the horror movie genre often called “slasher pics.”

I have to admit that I abhor and avoid most horror movies, especially slasher films. However, like many teens in the 1980s, I grew up on them and so I’m familiar with the overly used tropes and formula killings of those flicks. Anybody remember the rules of surviving a horror movie from Wes Craven’s 1996 movie Scream?

Several of the stories in Swift to Chase seem to follow this genre. We see wild parties at the homes of rich teenagers whose parents are away on a trip. (This seemed plausible when I was a teenager. But now that I’m in my 40s, I have to ask, why would any sane parent leave his or her teenager home alone for days or weeks?) These parties abound with all sorts of illicit behavior involving everything from sex to controlled substances. And there is a homicidal maniac lurking about with no apparent rational motive, and spurred on by seemingly unstoppable supernatural and evil forces.

But Barron has a unique way of presenting these tired tropes, especially in non-sequential diachronic plottings. They’re not really flashbacks per se. Jumping around to different and seemingly unrelated time frames, and focusing upon different and seemingly unrelated characters, Barron ties these together, as if by magic, with unsettling affects upon the reader where you feel like you’re always playing catch-up, and like you’re one of the teenagers being stalked.

There is also a running thread of many of the same characters over several decades throughout the different stories, with a special emphasis upon Barron’s favorite “final girl” Jessica Mace. Trying to unbraid the various interlocking story lines of these characters is part of the fun of this collection, though.

Barron separates his stories in Swift to Chase into three sections. The first, “The Golden Age of Slashing” focuses primarily upon Jessica Mace, where the stories are not in historical order either. In “Screaming Elk, MT” we are introduced to Mace and know that she is easily recognizable to many as the survivor of some awful event that had been all over the news a few years ago. But it’s not until we get to “Termination Dust” do we get any inkling of what that awful event was. Horror seems to follow Jessica Mace wherever life takes her. The various stories in this section recount these events.

Another recurring character, and arch-nemesis to Jessica Mace, is Julie Vellum. The last story in the first section focuses upon her in “Andy Kaufman Creeping Through the Trees.” If you know who Kaufman is, that title alone should creep you out. But even creepier, the late comedian’s character Tony Clifton plays a major part in the story. You should Google “Tony Clifton” if you don’t know who this is. A quick read on how this character was used by Kaufman is just enough to see the horrific possibilities Barron will play with in this story!

The name of the second section is where Swift to Chase takes its title. Though several of the same themes appear within, it is this section where the stories are most unlike the rest of the book. However “Ardor” in this section is most like Barron’s previous stories, focusing upon a private investigator who has been hired by a wealthy man to find his daughter who was last seen in a cult art film that seems to drive its viewers mad.

“Ears Prick Up” is the most different story here focusing upon a cyborg war dog and his master as they try to faithfully serve their futuristic but Rome-like state. This was hardly a horror story. Nevertheless, it also contains Barron’s great writing and his knack for zeroing in on cosmic and existential woes. If there is another theme that comes out in this book though, as this story highlights, it’s Barron’s deep love for canines.

The last section is called “Tomahawk” and comes back to Alaska, especially the last story “Tomahawk Park Survivors Raffle” which focuses upon Jessica Mace’s parents and their 70s generation. It shows us that Mace’s “final girl” role may be more fated than chosen.

Another story in this section, that has something of a surprise happy ending for a horror story, is “Frontier Death Song” where Barron turns real life horror writer and friend Steven Graham into a horror character. (Barron has done this in other stories as well, see his “More Dark” in The Beautiful Thing That Awaits Us All.) Barron appeals to mythic and folkloric accounts of the great hunt to structure this story.

Barron’s prose can be very punchy and taut, especially his character’s dialogue. And call me an old man, but his pop references can be a little idosyncratic at times. But Barron is not some hipster writer. He is often referred to as a literary horror writer, due to the fact that his writing is so rich, varied, and at times appropriately emotive. Particularly, Barron is excellent at having the horror pop up suddenly though it hardly ever comes off as cheap or below-the-belt. Rather than build slow burns, Barron is best at giving hints that foreshadow the future horrors.

In sum, Swift to Chase is an excellent horror collection that gives much of what good horror readers expect. Laird Barron continues to impress, giving some of his old stuff while also expanding on his artistic vision. I highly recommend it.

Swift to Chase was published by JournalStone in October, 2016. It comes in hardback, paperback and ebook.

James McGlothlin’s last review for us was A Shaper of Myths: The Best of Cordwainer Smith

I am very fond of Barron’s work and appreciate this enthusiastic review.

But I feel compelled to balk a bit at the “head-and-shoulders above any horror writer around today”. While others might advance any of a handful of active authors, I’d like to submit John Langan.

I think Langan’s The Fisherman might be the best full horror novel I’ve read since T.E.D. Klein’s The Ceremonies, and his collection, The Wide Carnivorous Sky is full of short stories that can take their place beside Barron’s best.

Feel free to balk away. I did preference it that comment with “to my mind” so as not to make the claim sound overly bold. But as far as my personal taste in horror goes, I stand by that claim.

I do love Langan’s short horror stories though. After Barron, my favorite current horror author is probably Nathan Ballingrud (but he writes so little). I also really like Philip Fracassi.

And oh T.E.D.Klein — oh that he would still be writing horror! His anthology *Dark Gods* is probably my favorite horror book of all time.

When he’s on his mark, (to my mind!) no one can top Thomas Ligotti. But like all writers with highly individual viewpoints and styles, his best work is often separated by barely a hair’s breadth from self-parody.

Ligotti is obviously a master. But, for my tastes, his stories leave me more with a nihilistic depression than a thrill of cosmic horror (I don’t know how else to put it) like Barron’s stories do.