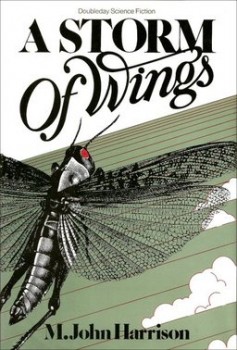

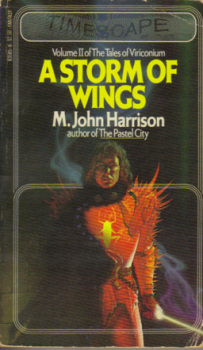

A Storm of Wings by M. John Harrison

Nine years, another novel, and ten short stories after the publication of The Pastel City (read last week’s piece on that here), M. John Harrison returned to the world of the city of Viriconium in A Storm of Wings (1980). Its title taken from a line in the previous book, A Storm of Wings largely recycles the plot of the that novel as well. Once again, alien forces are threatening the city of Virconium and only a ragtag band of heroes has a chance of staving off destruction. Other than setting and basic similarity of narratives, this second novel in the series exists on a whole different plane of storytelling, both in style and intent.

Nine years, another novel, and ten short stories after the publication of The Pastel City (read last week’s piece on that here), M. John Harrison returned to the world of the city of Viriconium in A Storm of Wings (1980). Its title taken from a line in the previous book, A Storm of Wings largely recycles the plot of the that novel as well. Once again, alien forces are threatening the city of Virconium and only a ragtag band of heroes has a chance of staving off destruction. Other than setting and basic similarity of narratives, this second novel in the series exists on a whole different plane of storytelling, both in style and intent.

A new religion has risen up in and around the city of Viriconium, the Brotherhood of the Locust. Its origins are a mystery and its teachings appear to have arrived from beyond mortal thoughts.

Who knows exactly where it began, or how? For as much as a century (or as little as a decade: estimates vary) before it made its appearance on the streets, a small group or cabal somehwere in the city had propagated its fundamental tenet — that the appearance of “reality” is quite false, a counterfeit or artefact of the human senses.

This creed stands at the nucleus of A Storm of Wings, both the story on the page, and at what Harrison has to say about fiction. As the “world” of Viriconium comes under attack from a force that twists and alters its “reality,” we are, page by page, reminded any stability the “land” has comes from its creator and can be wiped away with a tap of the backspace key.

Memory and perception are the other elements Harrison turns his eye to. Alstath Fulthor is the first of the Reborn Men, heroes from the ancient, Afternoon Cultures, brought back to life in The Pastel City. Eight decades after their destruction of the Northern Queen, their minds have begun to fragment and wander under the weight of their age and the psychic disconnect they feel at being out of time and place. Pieces of old dreams and mostly-forgotten memories haunt them, awake and asleep. Keeping the real and unreal separate is becoming increasingly impossible.

From The Pastel City, the ancient scientist, Cellur, returns, still unable to remember anything past two hundred years earlier. Between the two books, he spent the time trapped with machines that he had forgotten about, ones that he used to store his old memories just as he would start to lose them. Sadly, he learns, even transcribed electronically, they are imperfect and incomplete. As much information as it contains, it can’t tell him who he really is.

In each new incarnation, I must learn afresh how to operate the machinery. That is not hard. But to understand my purpose in being here at all…I can review ten thousand years, but I have no identity beyond that which I can scrape together in any one incarnation. I am, in short, nothing but what you see before you, an old man who has wandered into the city from the past…

Are we to feel sorry for Cellur as a character, or does he really serve as a reminder that his “memory” only exists to the degree Harrison creates it for him? Considering the games being played in Storm, it seems more the latter than former.

Finally, there is the new danger to Viriconium. Strange, gigantic insects have fallen to Earth from the Moon and started to build their own metropolis, distant from the Pastel City. Stellar travelers from some other part of space, they landed on the Moon ages ago and have now been drawn to Earth. Their physical presence in the world isn’t the danger, though. The jeopardy facing Viriconium comes from the insects different comprehension of reality. From the island they have occupied, a wavefront of change sweeps outward, crashing over Viriconium, seeking to supplant and supersede its own nature. Images of their city’s towers flicker and shine superimposed across those of Viriconium. A coastal town and its lord, are struck by visions of insects and danger in an omnipresent fog that may be real, or they may not.

Finally, there is the new danger to Viriconium. Strange, gigantic insects have fallen to Earth from the Moon and started to build their own metropolis, distant from the Pastel City. Stellar travelers from some other part of space, they landed on the Moon ages ago and have now been drawn to Earth. Their physical presence in the world isn’t the danger, though. The jeopardy facing Viriconium comes from the insects different comprehension of reality. From the island they have occupied, a wavefront of change sweeps outward, crashing over Viriconium, seeking to supplant and supersede its own nature. Images of their city’s towers flicker and shine superimposed across those of Viriconium. A coastal town and its lord, are struck by visions of insects and danger in an omnipresent fog that may be real, or they may not.

The members of the Brotherhood of the Locust seem most susceptible to this, becoming altered and damaged. Wings and feelers grown from their bodies, compound eyes replace their own. The lunar insects experience the same thing in reverse.

Their grey wing cases and armoured yellow underparts were crosshatched with self-inflicted wounds. From these wounds were growing like buds a variety of pink new half-human limbs, joined to the pricked and rotting carapaces by a transitional substance, membranous, neither flesh nor chitin. There were clumps of little hands with mobile, perfect fingers, each one having a tiny fingernail like mother-of-pearl. There were the faces of very young children with closed eyes.

To avert this horror, are the two previously mentioned characters, Alstath Fulthor, and Cellur. Joining them are another Reborn, the Lady, Fay Glass, and the assassin, Galen Hornwrack, and another veteran of The Pastel City, Tomb the dwarf. What the reader is to make of the fact that Hornwrack shares his first name with the murdered sister of the previous book’s protagonist, tegeus-Cromis, other than another bit of deliberately jarring authorial intent, I’m not sure.

Unlike his companions, stripped of their memories or subjected to too many simultaneously, Hornwrack possesses some actual density of character. Once a member of the landed gentry and a member of Viriconium’s airboat corps, he lost everything following the end of the war against the Queen Canna Moidart and the Northern barbarians. Though, now he lives in the city of Viriconium, he hates it and wishes to do nothing for it or the queen. When revealed, his reason for his animus has little to do with his loss of wealth and status. Definitely not part of Viriconium’s hierarchy or the heroes who seem to dominate the events of its history, his struggle to avoid throwing in with, despite seeming a deliberate part of Harrison’s “theory of power structures”, it reads genuine and possessed of real emotional weight.

Harrison might eschew worldbuilding, but this book is replete with it — just not in a typical fantasy novel fashion. Far more than in The Pastel City, both the city and the land of Viriconium blush with life in A Storm of Wings. Districts, street people, and denizens of street markets and cafes are described constantly. Little bits of color are dropped into paragraphs between parentheses across the book. Outside of the city, the land and other towns are breathed with as much vitality as well.

Harrison might eschew worldbuilding, but this book is replete with it — just not in a typical fantasy novel fashion. Far more than in The Pastel City, both the city and the land of Viriconium blush with life in A Storm of Wings. Districts, street people, and denizens of street markets and cafes are described constantly. Little bits of color are dropped into paragraphs between parentheses across the book. Outside of the city, the land and other towns are breathed with as much vitality as well.

On the surface, A Storm of Wings tells its tale in a linear way. Along the way, though, there are digressions to the past, where characters fill in some of the missing gaps explaining the current course of events. Of course, as with every other memory presented in the book, they are whole-filled and incomplete. A few chapters appear to be from the perspective of the insects reflecting on what happened during their journey to Earth. Much of the rest of the story is told in refracted and fractured ways. At times it becomes as challenging for the reader as the characters to understand exactly what is going on. Sometimes it’s made clear later, other times it is not.

This is most assuredly not your typical heroic fantasy tale. The heroes are addle-minded or decidedly unheroic – even Tomb the dwarf, as much as he enjoys fighting, thinks of what he does as murdering. Like the citizens of Viriconium, it leaves the reader dazed and more than a little confused at the end. Despite sharing a similar structure with its predecessor, A Storm of Wings, is a more potent book, filled with headier feats of prose and narrative gameplaying. While The Pastel City remains an excellent heroic fantasy tale, I’m now able to perceive it best as the template for Harrison to build on and spin off from mad, wild, meta-fictional constructs. In an interview, Harrison said: “A good ground rule for writing in any genre is: start with a form, then undermine its confidence in itself,” he says. “Ask what it’s afraid of, what it’s trying to hide – then write that.” Too much heroic fantasy relies on a lazy adherence to simple tropes – the hero, the obvious enemy, etc. In this book, he is clearly taking it to task for that, and while you may agree with that, or not, it’s hard not to hear and engage with his argument.

Next week – a delay as I carry out my monthly short story round up.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him. Right now, he’s writing about Western movies.