The Complete Carpenter: Halloween (1978)

Uhm, Happy Early Valentine’s Day?

Uhm, Happy Early Valentine’s Day?

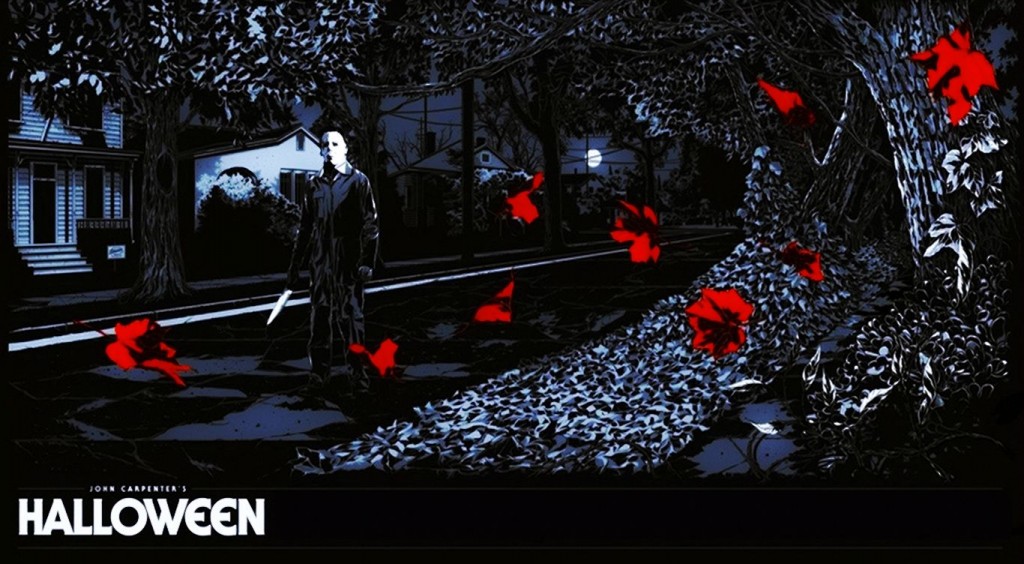

In my analysis of John Carpenter’s career, I’ve now reached his third movie, the low-budget horror smash Halloween. It’s Carpenter’s most financially successful film. It’s his most influential film. And, starting with a famous November 1978 Village Voice article by Tom Allen that helped turn the director into a recognized auteur, his most critically analyzed film. So here I tread, timorously, to add to the massive cultural heap of Halloween.

At least tackling the movie outside of October provides a feeling of freshness. February can’t always be dedicated to marathons of Groundhog Day. (Not that I’m opposed to that either.)

The Story

Do I really need to bother with this part? Okay, here ya’ go:

A psychotic killer (referred to as “The Shape” in the credits) who knifed his sister to death when he was six years old breaks free from a mental institute the day before Halloween. He returns to his hometown of Haddonfield, IL, puts on a white distorted Captain Kirk mask, and stalks and kills babysitters. His psychiatrist (Donald Pleasence) pursues him. One babysitter (Jamie Lee Curtis) survives the night. Every low-budget horror film then repeats this process over and over again until the last syllable of recorded time. Tales, told by mediocre filmmakers, full of breasts and blood, signifying nothing — except how great the original is.

The Positives

Psst … can I talk to you behind the scenes for a moment?

So, about a year ago I achieved my goal of owning all of John Carpenter’s oeuvre on Blu-ray (or widescreen DVD if there wasn’t yet a Blu-ray, which at this point means only Memoirs of an Invisible Man). Looking at all of them spread out in a mandala on the carpet of my bedroom, with my cat sprawled across Christine, I knew I had to write a movie-by-movie series of articles covering Carpenter’s career. It didn’t seem too ambitious or much of a burden: “Oh no, I have to watch all the movies of one of my favorite directors!”

But one film made me hesitate about the enterprise. Halloween. Because what more is there to say about it? When I started writing this section, this was my opening paragraph:

Some movies hover over all entertainment and seem to defy criticism — both positive or negative. They exist in our consciousness and subconsciousness and infiltrate our lives in ways which we’re often unaware. So is it with Halloween. Even people who have never seen Halloween have effectively seen Halloween.

I looked at that paragraph and decided it didn’t work as an intro because even that doesn’t need to be said. It’s essentially the same first paragraph anybody would use for an essay on Halloween written today.

So I’m going to jump into a story about my first exposure to John Carpenter’s most famous film. Using personal anecdotes in a literary or movie essay is sometimes a way to get too off-topic; but with a movie like Halloween that is woven deep into the fibers of the collective pop-culture unconsciousness, the personal is often the best tool to find out why something became a classic in the first place.

I didn’t see Halloween until I was nineteen because I was a skittish child who couldn’t handle any horror film. Ghostbusters was too much for me. Only when I started to love film on a new level as I entered college, becoming fascinated with movie history and filmmaking techniques, did I sit down to watch Halloween. The timing was ideal, since the movie had just come out on Laserdisc, formatted in its original Panavision 2.35:1 aspect ratio for the first time on home video.

I bring up Panavision because the wide frame is essential to how the film initially struck me. I didn’t actually find Halloween scary … because I was too swept up in how visually stunning and ingenious it was. From scene to scene, Carpenter and cinematographer Dean Cundey blasted my mind with their mastery of composition, camera movement, shot juxtaposition, and every inexpensive trick available to make an experience that was gripping from start to finish. The famous shot of the Shape’s white mask materializing slowly beside a shell-shocked Jamie Lee Curtis, like the moon coming from behind thick clouds, sent a shiver through my body — not of fear, but of excitement at how perfect the image was.

That was when I realized John Carpenter was a full-blown certified hall-of-famer genius. Halloween isn’t my personal favorite of his films (it would be nudged out of the top five, believe it or not), but it was the film that explained to me why Carpenter is such a towering figure. It also demolished any last prejudice I may have held against embracing low-budget genre films as potential major works of art.

That was when I realized John Carpenter was a full-blown certified hall-of-famer genius. Halloween isn’t my personal favorite of his films (it would be nudged out of the top five, believe it or not), but it was the film that explained to me why Carpenter is such a towering figure. It also demolished any last prejudice I may have held against embracing low-budget genre films as potential major works of art.

Halloween is built on the foundation of a straightforward story. It was, after all, something executive producer Irwin Yablans thought up in a few minutes when looking for a low budget horror idea: a serial killer stalks babysitters on Halloween. A solid exploitation movie concept. The script that Carpenter put together with his co-writer and producer Debra Hill is smarter than most exploitation horror scripts, but if the execution were drab and rote, none of it would’ve mattered; we probably wouldn’t be talking about the movie today. The style of Halloween is the rising tide that raises all ships. The whole movie is a crash course in how to use the camera to turn a small budget ($320,000) into a visual work of art.

Director of photography Dean Cundey is the MVP, not only of this movie but of the first part of John Carpenter’s career. Cundey already had a batch of low-budget films on his resumé when he did Halloween. He teamed up with Carpenter for six more films (two of which Carpenter produced rather than directed), became the favored photographer for Robert Zemeckis, and has worked with Ron Howard, Steven Spielberg, and Joe Dante. His credits also include Adam Sandler’s Jack and Jill … because even legendary cinematographers gotta eat.

Dean Cundey is a crucial part of the John Carpenter “look,” and there’s rarely been such a perfect melding of the interests of a director and a cinematographer. Cundey has an incredible eye for how to use the wide frame, which matches Carpenter’s own fascination with the potential of the format.

I could pick numerous examples of the technical mastery on display and how it creates tension and develops characters. I’ve already mentioned the Shape’s materialization over Laurie’s shoulder, which is not only a breathtaking visual but also the signal to ignite the white-knuckle chase finale. There are many examples of the moving camera, which creates a predatory feeling and an aura of lurking, even when something innocuous is happening on screen.

I could pick numerous examples of the technical mastery on display and how it creates tension and develops characters. I’ve already mentioned the Shape’s materialization over Laurie’s shoulder, which is not only a breathtaking visual but also the signal to ignite the white-knuckle chase finale. There are many examples of the moving camera, which creates a predatory feeling and an aura of lurking, even when something innocuous is happening on screen.

I’ll cite one other specific photography example, which is the shot where Annie Brackett is talking on the phone to her boyfriend while crossing back and forth across a kitchen. The camera sways with her, using the full horizontal space. In the French doors behind her, the Shape suddenly pops up after she crosses once. When she crosses back again, the Shape is gone, without the slightest indication of movement. It’s a simple trick, but the effect is electric.

Putting aside talk of the visuals (although they’ll creep back in anyway, since everything connects into them), there are a number of other elements that make Halloween work as well as it does:

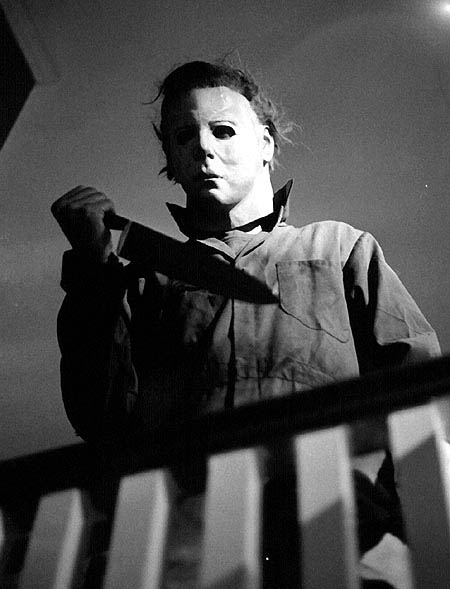

The Shape

The Shape provided Halloween its iconic image. The killer is anonymous and inscrutable, lacking even a name for viewers to grip on to. The name “Michael Myers,” used bluntly in the later entries in the series, is never spoken on screen here. We can infer it’s the murderer’s full name because we know the family name is Myers, and his sister and parents mention his first name in the opening scene. But once the prologue is done, the killer is only called “he,” “him,” and occasionally “it.” The name “The Shape” from the credits and marketing material is a perfect descriptor: the killer is a strange white shape lurking in background compositions. He pops in and out of shots to the point where the audience starts seeing him everywhere, even when he’s not present. The Shape is not so much a character as he is mise-en-scène.

Cultural overexposure of the Shape has denuded some of his power … until you return to the source and recall that this is the best slasher of the “classic” slasher movie era — and the neo-slasher era as well. The Shape is flat-out terrifying: silent, omnipresent, unrelenting, and mentally incomprehensible even to the person whose entire job is comprehending him. Dr. Loomis has to rely on the metaphysical concept of evil — something no real psychiatrist would utter regarding a patient — to grapple with the Shape: “I spent eight years trying to reach him, and then another seven trying to keep him locked up because I realized that what was living behind that boy’s eyes was purely and simply … evil.” The Shape just is; a horror that arose inexplicably from mundane suburbia and cannot be eradicated.

Cultural overexposure of the Shape has denuded some of his power … until you return to the source and recall that this is the best slasher of the “classic” slasher movie era — and the neo-slasher era as well. The Shape is flat-out terrifying: silent, omnipresent, unrelenting, and mentally incomprehensible even to the person whose entire job is comprehending him. Dr. Loomis has to rely on the metaphysical concept of evil — something no real psychiatrist would utter regarding a patient — to grapple with the Shape: “I spent eight years trying to reach him, and then another seven trying to keep him locked up because I realized that what was living behind that boy’s eyes was purely and simply … evil.” The Shape just is; a horror that arose inexplicably from mundane suburbia and cannot be eradicated.

We can attribute much of why the Shape works on screen to Carpenter and Cundey using visual trickery, such as the famous Panaglide long-take POV opening (actually two takes with a disguised edit). But performer Nick Castle deserves a share of the praise. Castle was a USC friend of Carpenter’s and later co-wrote Escape from New York before going on to his own successful directing career (The Last Starfighter). He’s far better playing the Shape than the professional stuntmen who later put on the white mask for the sequels. Castle’s sense of motionlessness and mental vacuity fits with how Carpenter treats the character. And who can forget the way he tilts his head back and forth with canine curiosity as he examines his handiwork of mounting poor Bob on a closet door with a knife? That’s both chilling and darkly hilarious.

Laurie Strode

Laurie Strode is a more layered and interesting lead than most of the generic Final Girls who followed her. Laurie isn’t painted as a lazy portrait of the “virginal good girl,” but rather as someone with more internal processes and a greater awareness of her environment than those around her. One brief scene does a remarkable job of showing why Laurie becomes the survivor: While in the back of her English classroom, Laurie gazes out the window and picks up on the distant figure of the Shape across the street. When the teacher calls on her, Laurie is caught off-guard, but then perfectly answers the question (on the topic of fate, appropriately). She’s aware of her surroundings while focused on the task at hand. That’s excellent character shorthand.

Laurie benefits from Jamie Lee Curtis’s naturalistic performance — she’s utterly convincing at playing sheer terror — and the scripting from Debra Hill. It was Hill who wrote much of the dialogue between Laurie and her friends Annie (Nancy Loomis) and Lynda (P. J. Soles). Carpenter knew he didn’t have a handle on the way teenage girls talk, and left it to Hill to infuse their scenes with her own high school experiences. These are real teenagers, something usually absent from the slasher imitations that came after.

Laurie benefits from Jamie Lee Curtis’s naturalistic performance — she’s utterly convincing at playing sheer terror — and the scripting from Debra Hill. It was Hill who wrote much of the dialogue between Laurie and her friends Annie (Nancy Loomis) and Lynda (P. J. Soles). Carpenter knew he didn’t have a handle on the way teenage girls talk, and left it to Hill to infuse their scenes with her own high school experiences. These are real teenagers, something usually absent from the slasher imitations that came after.

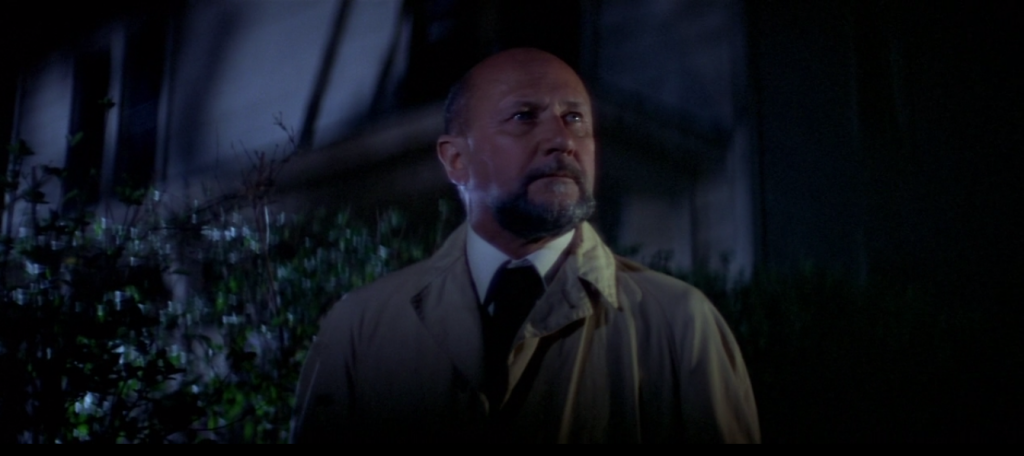

Donald Pleasence

I’m listing Donald Pleasence the actor as a positive, rather than Dr. Loomis the character, because Loomis as written isn’t the real success here. Laurie Strode works both because of Jamie Lee Curtis and how the screenplay uses her. Pleasence, on the other hand, livens up a standard monster-hunter/exposition-spouter role. Pleasance can make smirk-worthy lines like “He’s gone! The evil has gone!” and “Death has come to your little town, sheriff,” carry tremendous weight, and his intense visage makes anything he does feel urgent and a bit warped. There’s a touch of a Peter Cushing-style Hammer hero in him (in fact, Carpenter originally wanted Christopher Lee to play Loomis), but he’s off-kilter in that unique Donald Pleasence way.

Pleasence’s delivery also repairs one of the biggest plot holes, which is that the Shape somehow knows how to drive despite being in lock-up since age six. When the sanitarium head points out that the escapee can’t drive a car, all Pleasance has to do is shout, “He was doing very well last night! Maybe someone around here gave him lessons!” and that plot pothole is filled in.

The Music

Carpenter’s music to Halloween isn’t his best soundtrack work; I nominate Assault on Precinct 13 for that honor, and would also place the music from Escape from New York higher. But it’s so indelible to the film, as well as the holiday in general, that not ranking it as one of the finest horror scores ever is foolishness. The simple piano finger exercise main theme jangles viewers right into the fear zone. The moody minimalism elsewhere is nerve-wracking, with the hammering piano for the final chase ratcheting the tension up to delirious levels.

The Final Montage

The Final Montage

The Shape appears to survive the multiple bullets Dr. Loomis put in him and a fall from the second story of a house, since his body vanishes. The film then leaves audiences with a montage of shots that step backwards through the story’s key locations, all while the Shape’s breathing intensifies on the soundtrack. The final shot is of the Myers house, the place the film started. Did the Shape crawl back there to expire? Or is the evil now everywhere, unkillable? No matter the answer, it’s an authentically haunting conclusion. It superficially calls for a sequel, but it’s more powerful as the endpoint of this single movie.

Sheriff Leigh Brackett

The sheriff played by Carpenter company regular Charles Cyphers is named “Leigh Brackett.” That’s awesome.

The Negatives

I do have a legitimate complaint, which is what happens to Dr. Loomis once he reaches the Myers house: he stays hidden behind a hedge and does nothing through the middle chunk of the movie. Loomis’s main job of providing backstory to the killer is finished at this point, and since Halloween isn’t a exactly a “monster hunter” film (it’s about the monster’s victims and potential victims), he ends up unfortunately sidelined in the most literal way. All he does during his stakeout is make a scary voice to frighten away a pack of nosy kids, part of a scene that exists solely to remind viewers that Dr. Loomis is still around and so Sheriff Brackett can drop by for an exposition check-in. However, the look of satisfied pleasure on Donald Pleasence’s face after frightening off the kids is wonderful. Loomis is not quite right in the head himself.

Like most low-budget horror films, there’s lots to nitpick in Halloween, such as obvious signs the movie was shot in Pasadena in spring rather than Illinois in the fall. The crew did their best moving around the same pile of dead leaves from location to location, and the photography is suitably autumnal, but it’s impossible to disguise things like a school building with classroom doors that open directly to the outside. No school in Illinois is built like that. But with a movie like Halloween, nitpicking the details is just another way of enjoying it. (“Look, a wisp of smoke from John Carpenter smoking too close to the camera! Cool!” “Hey, P. J. Soles tripped on the dolly track in that shot! Neat!”)

The Pessimistic Carpenter Ending

You can’t kill the Boogeyman. Also, you can’t stop all those terrible rip-offs.

Next: The Fog

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Godzilla in interviews.

RE: Jack and Jill:

http://hijinksensue.com/comic/fetch-a-pail-of-water/

I admit I still haven’t watched Halloween. Should probably rectify that. I’ve never been a huge slasher movie fan — I don’t think I’ve ever seen a Friday the 13th either (except Freddy vs. Jason, which I watched because of the Nightmare on Elm Street connection).

@Joe – From somebody else who isn’t a slasher movie fan either, trust me that Halloween will still impress you.

My favorite Carpenter film.

Also, have you ever watched Bravo’s Inside Story: Halloween? A great documentary that runs every October. A great way to learn that, for example, Sheriff Leigh Brackett was named because Carpenter was a huge Rio Bravo fan and deliberately made Assault on Precinct 13 as an homage to Rio Bravo (hopefully at some point Carpenter tried reading some of Brackett’s wonderful novels and short stories, but I guess it’s only fitting that a filmmaker would think of her first as a screenwriter).

@Ryan Harvey

I sat in on a horror movie class at my university a few years ago. I was by far the oldest person (besides the professor) in the room. We watched Carpenter’s Halloween one week. You might be surprised that at the consensus of the 20-somethings present. Most of the students were thoroughly unimpressed with it. Though they understood the movie came first, they had seen all of the standard slasher movie ripoffs based upon it. Thus, to them, the movie seemed like fairly old hat.

Also, I just realized that sadly, Leigh Brackett would have died during the filming of Halloween. Had she lived, I wonder if Carpenter would have eventually hired her to write some screenplays for him?

@James – Depressingly, this reaction does not surprise me. I’ve heard similar stories about millennials who have just sort of shrugged at the movie because of cultural saturation. I believe that when those students are older they will re-discover the movie, and the technique is something they can appreciate.

@Amy – Yes, I’ve wondered too if Carpenter read any of Brackett’s SF&F fiction. I’ll bet he has, because he’s definitely an SF fan. But it was the Rio Bravo connection that made him use the name both here and in Assault on Precinct 13 (Laurie Zimmer’s character “Leigh”) at the time.

In 1974, a relatively obscure movie called BLACK CHRISTMAS was a smash hit where I live (Cape Town, South Africa). It was so popular that it was brought back for a second time about a year later. I saw it both times and I was terrified both times.

As the years went by, however, it seemed to be forgotten … until fairly recently. In the last decade or so, I’ve increasingly seen references to BLACK CHRISTMAS as an underappreciated masterpiece of the slasher genre, and perhaps even the inspiration for HALLOWEEN.

In fact, one of the reviewers on IMDB says:

“The original and maybe even the best, ‘Black Christmas’ set the ball rolling for the slasher genre and was the biggest influence for the phenomenally successful John Carpenter classic, ‘Halloween’ (1978), which was, in fact, originally conceived as a sequel.”

Ryan, I’d love to know what you think of that?

@dolphintornesa – I enjoy Black Christmas, and it’s definitely one of the earlier examples of what we’d count as a “slasher.” The connection to Halloween is explored in this article at Bloody Disgusting, where director Bob Clark recalls having a conversation with John Carpenter about his idea for a sequel to Black Christmas, although he then says he doesn’t think Carpenter really copied him. As the article then goes on to say, the usual story about Halloween‘s inception is that executive producer Irwin Yablans thought up the idea and then called Carpenter about directing it. This is what Yablans says on the “Making Of” documentary found on a number of Halloween DVD and Blu-ray releases.

So the truth is… I dunno. Memories are strange, especially for a movie working up to its 40th (yipes!) birthday. I’m certain Carpenter saw Black Christmas and it had an influence, but I’m more inclined to believe Yablans as thinking up the Halloween-babysitter-killer concept (maybe he talked to Bob Clark?). These things get so tangled. But we got a good film and great film out of whatever it was that happened.

Sad story: Bob Clark’s fatal car crash occurred in the town where I grew up, Pacific Palisades, CA.

Edit: Here’s a fun article from Horror-Movie-a-Day guy Brian Collins about why he loves Black Christmas. Brian is one of the reasons that the film’s profile has risen in years.

Ryan wrote: “Using personal anecdotes in a literary or movie essay is sometimes a way to get too off-topic; but with a movie like Halloween that is woven deep into the fibers of the collective pop-culture unconsciousness, the personal is often the best tool to find out why something became a classic in the first place.”

Yes, this!

It’s the approach I tend to take (granted, it’s also why I sometimes get too off-topic). But then, sometimes getting far afield of the thematic thread and somehow tying it all together again can also be a fun surprise — same goes for stand-up comedy.

The master at this was G.K. Chesterton. He’d start an essay ostensibly about Robert Louis Stevenson, then go for a page and a half not saying anything about Stevenson but talking about, I dunno, his favorite cafe or a walk he took to the pub: And by the end, you realize he’s really actually illuminated your understanding and appreciation of Stevenson! More than that, he has used Stevenson to shed light on the culture and say something about the world.

P.S. That said, your post was not a meandering walk down various side routes that eventually came back on track. It was, rather, an on-point and spot-on summary of why the film is appropriately revered. Whole reams may have been written, but such succinct overviews are still much welcome (especially for new potential fans who won’t read all that stuff that’s been written already).

One more word on injecting a bit of personal perspective into a review: Roger Ebert (one of our greatest film critics) was a staunch proponent of that approach. It helps the reader to know where you’re coming from and to factor that into your critique.

Ebert was also a staunch defender of Halloween!

Ebert was a writer who was superb at using the personalized approach; he was a great example of the film essay as a piece of literature that can stand on its own. (On the negative extreme, I once read a movie review where the writer, on a major site, decide to use a big chunk of a review to complain about his ex-wife.)