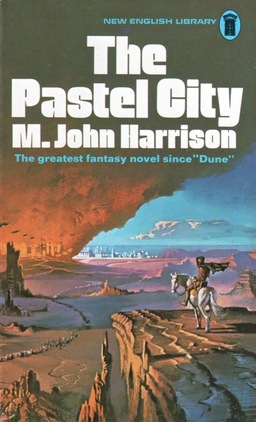

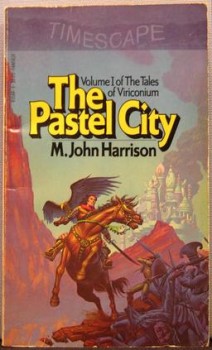

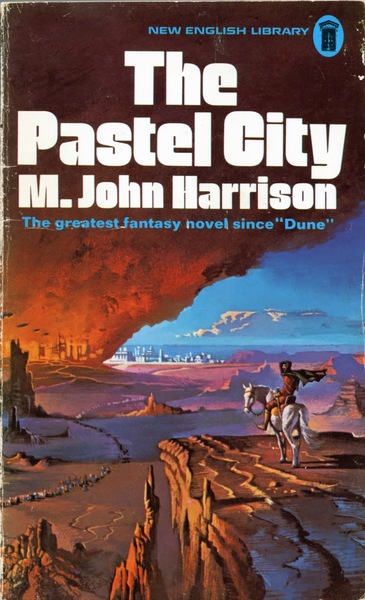

The Pastel City by M. John Harrison

M. John Harrison, like Joan Vinge or J.G. Ballard, hails from my terra incognita of the universe of sci-fi/fantasy authors. Over the years I’ve read praises of his fiction but have never read a word of it. Searching my shelves for something to review this week, I saw a copy of the Bantam omnibus of his novels and stories of Viriconium, a city in the twilight days of Earth. I have no memory of how, when, or where it came into my possession, but there it was. So I figured it was about time to investigate its unknown literary landscapes.

M. John Harrison, like Joan Vinge or J.G. Ballard, hails from my terra incognita of the universe of sci-fi/fantasy authors. Over the years I’ve read praises of his fiction but have never read a word of it. Searching my shelves for something to review this week, I saw a copy of the Bantam omnibus of his novels and stories of Viriconium, a city in the twilight days of Earth. I have no memory of how, when, or where it came into my possession, but there it was. So I figured it was about time to investigate its unknown literary landscapes.

Harrison came to my attention from a pair of essays he wrote on the creation of fantasy. The first, “What It Might Be Like to Live in Viriconium,” is an attack on the effort to codify and specifiy the nature of fantasy. It opens with this bold statement:

The great modern fantasies were written out of religious, philosophical and psychological landscapes. They were sermons. They were metaphors. They were rhetoric. They were books, which means that the one thing they actually weren’t was countries with people in them.

For him, any effort to delineate geographical boundaries and the like in a work of fantasy undermines what really lies at its heart. He describes his own tales like this:

“Viriconium” is a theory about the power-structures culture is designed to hide; an allegory of language, how it can only fail; the statement of a philosophical (not to say ethological) despair. At the same time it is an unashamed postmodern fiction of the heart, out of which all the values we yearn for most have been swept precisely so that we will try to put them back again (and, in that attempt, look at them afresh).

The second essay “about why storytelling must take precedence over worldbuilding,” continues and extends the argument of the first with more vehemence:

Worldbuilding is dull. Worldbuilding literalises the urge to invent. Worldbuilding gives an unneccessary permission for acts of writing (indeed, for acts of reading). Worldbuilding numbs the reader’s ability to fulfil their part of the bargain, because it believes that it has to do everything around here if anything is going to get done.

Harrison makes a complex argument that intricate worldbuilding limits the ability of the reader to interpret the story. It undercuts real reading, which is a transaction between the reader and the text. His ideas make for confrontational reading in our current age of unending series. How many of us enjoy losing ourselves in a trilogy because we want to become lost in an author’s hyper-detailed secondary world, where we learn about everything from the ingredients in each dish at the feast, to exactly how the king’s regiments are organized, and the intricate details of court politics?

Harrison makes a complex argument that intricate worldbuilding limits the ability of the reader to interpret the story. It undercuts real reading, which is a transaction between the reader and the text. His ideas make for confrontational reading in our current age of unending series. How many of us enjoy losing ourselves in a trilogy because we want to become lost in an author’s hyper-detailed secondary world, where we learn about everything from the ingredients in each dish at the feast, to exactly how the king’s regiments are organized, and the intricate details of court politics?

Because of pre-conceived notions I’d had about Harrison’s stories, I was surprised to discover that The Pastel City (1971), is a fairly orthodox Dying Earth tale. Numerous far-future civilizations have risen and fallen on Earth. Mighty technologies are used but are no longer understood, and must be scavenged from the great wastelands left by vanished cultures. Viriconium exists so far into the future that the world of today is not even a lost memory.

Some seventeen notable empires rose in the Middle Period of Earth. These were the Afternoon Cultures. All but one are unimportant to this narrative, and there is little need to speak of them save to say that none of them lasted for less than a millenium, none for more than ten; that each extracted such secrets and obtained such comforts as its nature (and the nature of the universe) enabled it to find; and that each fell back from the universe in confusion, dwindled, and died.

The basic plot of the story: aged hero straps on his sword one last time and sets out to save the queen, the daughter of his old lord. The hero is Lord tegeus-Cromis and the queen, who rules under the name Methvet, is really named Jane.

Queen Jane and her rule of Viriconium, the Pastel City, are under assault from her cousin, Queen Canna Moidart. The issue of a failed royal marriage between Jane’s uncle and the queen of the Northern barbarians, Canna Moidart has tried to force her claim to the throne of Viriconium with hordes of warriors and mysterious constructs dredged up from the ancient ruins of the Afternoon Cultures.

Under Jane’s father, tegeus-Cromis was one of a select band of heroes known as the Methven, the name of their king. Together they helped avert a coming Dark Age, but upon their success and the death of the king, they disbanded and went their separate ways. tegeus-Cromis, who always “imagined himself a better poet than a swordsman,” retired to a tower by the sea. Only when a supporter of the Northern queen tries to kill him does he decide he must do something to help his liege’s daughter.

As the war against Queen Jane intensifies, with riots in the streets of Viriconium and invading armies nearing the border, all but one of the Methven reappear. Next to tegeus-Cromis are Birkin Grif, Tomb the dwarf, and Theomeris Glyn. The whereabouts of the great strategist, Norvin Trinor, becomes an important part of The Pastel City‘s narrative.

You can read TPC as a simple story of adventure and derring-do. On that level alone, it is exciting and wonderfully well-told. There are mysterious brain-stealing monsters, talking robot-birds, betrayals, and a fair amount of swordplay, but for the deeper reader there is more.

Themes of stasis, decay, and time permeate the book. The missing Norvin Trinor fled Viriconium because he felt it had lost its vitality and was sinking back into decline. Failure of both the barbarians and the people of Viriconium to fully comprehend the recovered technologies of the old world typify a greater lack of societal energy.

|

|

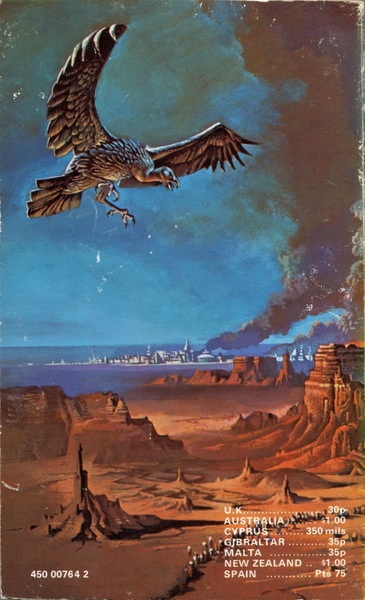

Art by Bruce Pennington

Viriconium — its civilization, its culture, its technology — is stuck in a rut, forever spinning but never moving forward. The scholar Cellur is so old he has no idea of who or what he is anymore. The past is unknowable, crumbling away behind him the same way the Afternoon Cultures lie crumbled around the outskirts of Viriconium.

That is the curse of the thing, you see: the memory does not last. There is little enough space in one skull for a lifetime’s memories. And no room at all for those of a millennium.

Time in Viriconium appears to be a loop. The climax of the novel doesn’t result in the restoration of the old regime, but that of an earlier time, of the Afternoon Cultures and all their flaws and failings. Harrison gives us a hint that Time isn’t really a moebius strip, though. When tegeus-Cromis and his companions are fleeing through the glacial moors of the region called Rannoch, he is struck by something calling to him:

Something in the resigned, defeated landscape (or was it simply waiting to be born? Who can tell at which end of Time these places have their existence?) called out to his senses, demanded his attention and understanding.

He never found out what it was.

It is human effort to impose order on chaos that creates the sense of cycles and loops. Time itself remains something that stretches out endlessly back and forward.

The Pastel City is an incredibly traditional story: its start and finish clearly marked, its characters recognizable archetypes (ex. the knight of the dolorous countenance, the absent-minded wizard, etc), and its typical arc of resistance, defeat, and victory. Perhaps, having first read “What It Might Be Like to Live in Viriconium,” I expected more of a departure. For years I have read how Harrison played games with his texts, and there’s not much of that.

The Pastel City is an incredibly traditional story: its start and finish clearly marked, its characters recognizable archetypes (ex. the knight of the dolorous countenance, the absent-minded wizard, etc), and its typical arc of resistance, defeat, and victory. Perhaps, having first read “What It Might Be Like to Live in Viriconium,” I expected more of a departure. For years I have read how Harrison played games with his texts, and there’s not much of that.

Instead, there is a well-written and well-told tale in which are lifted up such noble sentiments as honor, obligation, and sacrifice. Harrison created a story to which it is indeed possible to attach “the values we yearn for most.”

It is with the two subsequent novels, A Storm of Wings (1980) and In Viriconium (1981), and the collection Viriconium Nights (1984), that Harrison began to really explore the sentiments expressed in his two essays. For the next three weeks I’ll look at his books in sequence, and follow where he went during those explorations.

The Viriconium books have been written about previously at Black Gate by both Matthew David Surridge, and, in the very first Black Gate blog post, Howard Andrew Jones.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

I enjoyed the Viroconium sequence, but really felt Harrison came into his own in late middle-age. The next thing I read by him was years later – “Space: A Haunting”, a book I’ve only belatedly realised is something of a classic (I hadn’t read any SF in around ten years and this particular book marked my return to the genre: only now can I put it on context). It’s a subtle blend of SF tropes with the very best sort of literary fiction. You have been warned!

Aonghus,

I know that book! It was released in trade paperback by Night Shade in 2013.

Hmmm….I think the Night Shade cover is a tad nicer than its UK equivalent –

Wow, I’d never heard of Harrison. I’m going to have to look for the Viriconium stories. I found the essays you linked quite stimulating; they resonate with a lot of my vague thoughts about commercial world-building. Too often the “world” is more like a sandbox, and it’s hard to care about what happens in a sandbox. Part of what I like about sword-and-sorcery is that the action is localized, with lots of unknowns on the periphery. There’s no big picture, which means that there’s always room to stumble on something new and unexpected.

I disagree with Harrison’s assessment of Tolkien in the second essay. To my mind, Tolkien’s Middle-Earth doesn’t at all reflect what he describes (rather inaccurately, IMO) as the “fundamentalist Christian” view of the world as a watch with God as the watchmaker, of which the secondary world is a “secularised, narcissised version.” (The watch analogy is an already-secularized Deist idea, not a “fundamentalist Christian” idea, but that’s neither here nor there.) I think it’s possible to distinguish between Tolkien’s conception of secondary creation and the sandbox-building some of his imitators have engaged in; I also find Tolkien more playful than Harrison admits, and quite conscious as an author that he’s engaged in a game.

But I think “What It Might Be Like to Live in Viriconium” has it exactly right: “The commercial fantasy that has replaced [the great modern fantasies] is often based on a mistaken attempt to literalise someone else’s metaphor, or realise someone else’s rhetorical imagery… Literalisation is important to both writers and readers of commercial fantasy. The apparent depth of the great fantasy inscapes – their appearance of being a whole world – is exhilarating: but that very depth creates anxiety. The revisionist wants to learn to operate in the inscape: this relieves anxiety and reasserts a sense of control over ‘Tolkien’s World.'” Exactly!

My favorite MJH is the Centauri Device, a no-holds-barred attack on space opera in the form of an absolutely ripping space opera.

I’d agree with you about S&S, Raphael – a very real part of its charm is that it doesn’t rely on exhaustive world-building. The writer has a lot of room to come up with new stuff (that doesn’t have to be integrated into some sort of over-arching mythos) and the reader can look forward to being constantly surprised – but maybe this has as much to do with the typical S&S format: the short story?

I think Harrison is being too prescriptive about world-building. A less talented writer will often try too hard – ie, a lot of excess descriptions of clothes, weaponry etc that aren’t strictly relevant. In this respect, I was surprised when somebody pointed out recently that in ‘The Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe’, the description of the lamp-post is as follows – ‘She began to walk forward, crunch-crunch over the snow and through the wood towards the other light. In about ten minutes she reached it and found it was a lamp-post.’

In other words, Lewis uses the minimum amount of words to set the scene; the whole appeal of the image lies in the notion of a lamp-post in a middle of a wood. There’s no need to embellish on it. But when he describes authors as trying to mimic God via sub-creation, Harrison ignores the writers of dystopian fantasies, like George Orwell or Lovecraft.

As for codifying a world being a way of trying to control it, maybe so – but it’s also one way readers vicariously participate in books which they happen to love.

Aonghus — Yeah, I agree that there are practical, even commercial, reasons why S&S is the way it is. There’s the short-story format, as you mention, plus the fact that, if you’re careful, you can prolong the exploration of your Hyborean World (or whatever) indefinitely, without worrying too much about overall consistency. That’s perfect for a writer who has to write fairly quickly but without the assurance that any given story will be accepted by any given market.

That’s a point well-taken about the lamp-post.

This sounds interesting.

Ultimately, world-building can be a wonderful tool or a hindrance. It comes down to the author. Robert E. Howard engaged in far more serious world-building than some realize, though a great deal of it was “on the fly”, as it were. Clark Ashton Smith was fairly meticulous about things. Leiber seems to have winged it.

I like this book, and consider it one of the minor masterpieces of Sword & Sorcery/Heroic Fantasy. The second time I read it, I felt it was shorter than I wanted it to be.

I agree it is rather traditional, but I enjoyed it more than his other Viriconium stories for precisely that reason.

I agree completely on world building USUALLY being an unnecessary and even harmful exercise for a fantasy author. I don’t think Tolkien was really world building. He was a linguist. He wrote mythical languages and then created a world for those languages through writing stories (not manuals). Leiber said he never knew more about Newhon than was in his stories. I’m not a Howard expert, but I don’t think he did much world building as it is thought of now (usually like a role-playing game approach), and wrote the history of The Hyborian Age to maintain consistency throughout the stories that were coming to him so quickly. Again, I am no expert and willing to be corrected on any of this.

I feel strongly that this gaming approach to writing fantasy as approached to focusing on literary quality and story telling is what makes much modern fantasy suffer in comparison to the classics.

As for Harrison, he gets a bit too pedantic for me with his ideas of what his fiction is. Just write it. Let other people decide for themselves. Focusing on what your work means usually creates the kind of didactic sermonizing work he complains about. And at the other end opposite that is escapist pornography, which is what much modern fantasy seems to be. I think the more a writer writes without getting in the way of their own work (ego) and without too much concern of pleasing others, the better chance they have of creating something meaningful that will move people and stand the test of time.

Brief Addendum:

“World building” would have to be defined to have a substantive discussion on the topic. I would simply say that any world building that is done should not in any way limit the writing. Because, if you’re a writer, writing is when the real inspired creation takes place.

I once drew a map and wrote a short history for the world where my stories take place (Plemora), but I mostly threw them out as soon as I finished. I only did that to give myself some ideas and clarity. What I wrote since then has already grown beyond those two information items, and I’m certainly glad I didn’t use them as guidelines for what I could and couldn’t do.

And, thanks for the article, Fletcher!

@Aonghus – That’s intriguing – onto to the TBR pile.

I agree with your responses to Raphael. There’s a place for “sermons” (by which I’m assuming he means the liked of JRRT, Lindsay, Peake, etc) in fantasy and detailed secondary worlds that he rejects. He also seems to demand a story force a confrontation with the real world.

@Raphael – After rereading the essays, I immediately thought of you. I’ll address them more directly along the way, but I agree with you. The conflation of Deism and fundamentalism almost made me do a spit take.

@Thomas P – It sounds good, even though MJH himself hates it

@deuce – Yeah, it’s got it’s place – and MJH does a fair amount in TPC. It’s something that’s gotten out in fantasy though.

@Robert Z – You’re welcome!

I lay the sin of excessive worldbuilding at the feet of gaming. When I gamed, I felt obligated (and enjoyed) to have every detail at my and my players’ fingertips. I think the familiarity with that helped lead a lot of readers to want that in their fiction. MJH is pretty pedantic, though considering the massive success of ponderous slab-like books packed with maps and obnoxious levels of detail about stuff and nonsense, I appreciate his degree of reaction.

I don’t really follow MJH’s highbrow essays on story telling, but I thought “The Pastel City” was a fantastic book. It’s probably one of my favorite fantasy novels. Unfortunately I haven’t heard the same praises for the other Viriconium novels. I do need to check out some of his science fiction, though.

@Robert: “I’m not a Howard expert, but I don’t think he did much world building as it is thought of now (usually like a role-playing game approach), and wrote the history of The Hyborian Age to maintain consistency throughout the stories that were coming to him so quickly. Again, I am no expert and willing to be corrected on any of this.”

Well, I call “worldbuilding” writing down stuff about the world that doesn’t immediately impact a given story. I don’t give a damn how Greenwood or Salvatore did things. Looking at worldbuilding in such an extreme fashion is similar to what has narrowed being a “hero” to the point that only Superman and Dudley Do-Right are “heroes” and everyone from Batman to Woody Allen are all idiotically lumped under the “anti-hero” label.

Robert E. Howard wrote FOUR drafts of “The Hyborian Age”. He also wrote his “Notes Concerning Various Peoples of the Hyborian Age”. He also drafted THREE maps. Those are just what has survived. Sounds like worldbuilding to me.

When I first began reading Leiber’s F&GM tales, I had no idea whether he had spent any time worldbuilding. However, I quickly began to realize that, outside of Lankhmar, things got a little “thin” as far as “historical depth” in those stories. Don’t get me wrong, I love them, but it’s there and I sensed it from the start. That goes triple for Cook’s “Black Company” books.

I never sensed that reading REH or JRRT.

^^^That’s one of the things that I’ve noticed about REH’s stories that set them apart from other S&S. They all had a real sense of history to them as if the places and things he wrote about had already existed for thousands of years. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Howard seemed to have a real love of history also. No one ever seems to talk about this in their essays of him, though.

The Pastel City is one of my favorite novels. I discovered it back when I was in jr. high, back in the mid-80s. It stayed in the back of my mind for around 15 years and I eventually bought a copy and re-read it; probably read it a dozen times by now. I eventually bought the follow-up Viriconium novels (in the collection shown above) with much anticipation and excitement… I was sorely disappointed, unfortunately. I’ll always have The Pastel City, though.