The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: Not Impressed With “The Mazarin Stone”

Current writers of Sherlock Holmes stories (such stories are known as ‘pastiches’) are held to the standard of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s originals. And rightfully so. But that’s not to say that all sixty of Doyle’s tales featuring his famous detective are of the same quality. Followers of the great detective debate the merits of various stories. I myself am less than thrilled with “The Dying Detective,” since Holmes doesn’t do much of anything in it. He’s less mobile than Nero Wolfe in that one.

Current writers of Sherlock Holmes stories (such stories are known as ‘pastiches’) are held to the standard of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s originals. And rightfully so. But that’s not to say that all sixty of Doyle’s tales featuring his famous detective are of the same quality. Followers of the great detective debate the merits of various stories. I myself am less than thrilled with “The Dying Detective,” since Holmes doesn’t do much of anything in it. He’s less mobile than Nero Wolfe in that one.

But I can’t think of too many fellow Sherlockians (and I don’t mean followers of the BBC television show) who are enamored with “The Mazarin Stone.” I definitely am not and consider it one of the weakest in the entire Canon. Of course, if you haven’t read it, you probably should do so before continuing. You’re back? Good.

The Play’s the Thing

Jack Tracy’s The Published Apocrypha contains the full text of the play The Crown Diamond, as well as an informative essay. “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone” and The Crown Diamond are pretty much the same story and share much dialogue, differing only in a few minor details.

One of those details worth noting is that Colonel Sebastian Moran is the villain in play, whereas it is Count Negreto Sylvius in the story. Using Moran makes sense, since playgoers likely would know the character, based on his feature role in “The Empty House.” Both men like air guns and are big game hunters, so the real difference is negligible.

Dennis Neilson Terry starred as Holmes in the stage production of The Crown Diamond. It’s nowhere near as good as Doyle’s play, The Speckled Band, which I wrote about in this post.

A Lazy Tale

I really do think that this story is quite possibly the weakest of all Doyle’s Holmes tales. It has the feel of being rushed out to coincide with the performance of The Crown Diamond.

Examples of the unusual details found and the lack of quality usually present in a Holmes adventure:

– It is told in the third person, one of only two out of sixty not overtly narrated by Holmes or Watson;

– It contains the only mention of a waiting room;

– It contains the only mention of a secret exit from Holmes’ bedroom;

– It contains the only mention of an electric bell to summon someone;

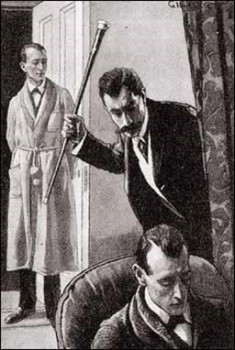

– The only thing preventing Holmes from having Count Negretto Sylvius arrested is the fact that the detective doesn’t know where the Mazarin stone is. So of course, the villain, knowing Holmes is in the next room, reveals his plans for the stone and takes it out of a secret pocket. Naturally, the hidden Holmes grabs it;

– Holmes substituting himself for the dummy without the villains noticing stretches credulity;

– Holmes tells Watson he may well be murdered by the Count. With the Count about to come into the room, Holmes tells Watson to go fetch the police. Watson hurries off without a protest, even though it is quite possible Sylvus will kill Holmes while the doctor is gone.

Reinvented by Granada

Jeremy Brett was in ill health when it came time for Granada to begin production on its adaptation of “The Mazarin Stone” and the script was extensively rewritten from Doyle’s original story. Count Sylvius possessed the stolen Mazarin stone, but that was about the only similarity. Sherlock Holmes was barely present and played no part in solving the case.

Jeremy Brett was in ill health when it came time for Granada to begin production on its adaptation of “The Mazarin Stone” and the script was extensively rewritten from Doyle’s original story. Count Sylvius possessed the stolen Mazarin stone, but that was about the only similarity. Sherlock Holmes was barely present and played no part in solving the case.

His brother Mycroft stepped in and recovered the missing gem. There was also no wax dummy or violin recording (which was actually an improvement over the story). Sylvus’ associate, the boxer Sam Merton, is also left out of the show.

The episode opens with a weird dream sequencing mixing the Reichenbach Falls, Sherlock Holmes and a third eye in the middle of Brett’s forehead (the kind of nonsense BBC Sherlock would later make standard Holmes fare, sadly).

We see a haggard looking Brett again at the end of the episode, congratulating Mycroft on finding the gem. There is more mumbo jumbo mysticism in this episode than in any other of the Granada series.

This story was a strange choice for adapting in the first place, and the pick seems even odder when considering the extent to which it was completely reworked. Granted, part of the extensive revision was due to Brett’s illness, but even if he had been healthy, how good could this adaptation have been, based on the source material?

A script for “The Reigate Squires” had been written for The Adventures but never filmed. Surely it would have been more suitable for the series. Charles Gray is a more than satisfactory Mycroft, and it is nice to see him at center stage, but for a series about Sherlock Holmes, this episode is certainly outside the normal bounds.

Watson as the Author

Now, to play The Game a bit. Theories abound as to who the real author of the story is, including Dr. Watson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Watson’s wife (the former Mary Morstan), Billy the page and an unidentified person who wrote it up from Watson’s notes.

I support the ‘Watson as author’ theory, but for what I believe is an original reason. The Crown Diamond opened on May 2, 1921. Compared to William Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes and Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Speckled Band, The Crown Diamond was not a very successful Holmes play.

And yet another element is the series of silent films starring Eille Norwood. The first fifteen Eille Norwood shorts, collectively known as The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes, appeared in 1921 and were quite popular. The Crown Diamond was suffering in comparison to these three productions.

Though credited to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Watson certainly had to have a significant role in the writing of The Crown Diamond. The Strand was preparing to publish “The Mazarin Stone” in October and the story was clearly derived from the play. In fact, it may well have been the earliest example of a novelization tie-in (the stage having since been supplanted as the source material by films and television for such “quickie” books).

For whatever reasons (quite possibly easy money: it has been known to happen), Watson was determined to go forward with his new Holmes story. But rather than have his name tied to a weak story, based on a less-than-wildly successful play, he quickly reworked his manuscript as a third person story.

Now he would still be paid, but his name would not be identified as the author of this forgettable Sherlock Holmes adventure. This ploy apparently worked, as the debate over authorship still exists today.

You can read Bob Byrne’s ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column here at Black Gate every Monday morning.

He founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV and V (and the upcoming VI).

Interesting post, Bob, and I’m in full agreement as to the weakness of the story.

An aside: I finished reading TEN YEARS BEYOND BAKER STREET a few days ago, and was disappointed. It seemed overwritten, with scenes completely unnecessary to the plot, Dr. Petrie being dumber than the dumbest screen version of Watson, and a Holmes who seemed to pull solutions out of a hat instead of using his famous logic. I’d intended to read it for over a decade, but now that I have, I couldn’t recommend it.

R.K. – Van Ash was considered the pre-eminent Fu Manchu scholar. Maybe he just wasn’t that good at Holmes.

I have to admit, in the couple of Fu Manchu stories I read, Petrie did seem a bit of dead weight. Nayland Smith absolutely was the crime fighter of the pair.

Quite fair, though I’m surprised you didn’t also pick on The Musgrave Ritual, which is technically unworkable if you dissect it.

Carfanel – I quite enjoy ‘the Musgrave Ritual.’ Where do you find it unworkable?