The Killingest Book I Know: The Twelve Children of Paris by Tim Willocks

“It is night and the night has no end.”

Matthias Tannhauser

I have read all sorts of hyper-violent books: thrillers; crime; horror; even some fantasy. Nothing, and I mean absolutely, utterly nothing, comes close to Tim Willocks’ The Twelve Children of Paris (2014). Seven years after his adventures during the Great Siege of Malta chronicled in The Religion (and reviewed here), Matthias Tannhauser, ex-Janissary and current Knight of St. John, comes to Paris in search of his wife, Carla. It is August 23rd, 1572, just hours before the start of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre.

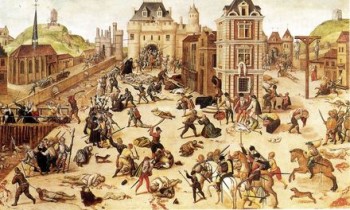

The massacre was the result of the tremendous instability the Reformation had caused to France. During the ten years preceding the massacre, France had fought the first three of the Wars of Religion. Primarily a struggle between two noble houses, the Calvinist House of Conde and the devoutly Catholic House of Guise, the kings strove to maintain a balance between them and avoid bloodshed. When it seemed the Protestants had gained too much power and threatened that of King Charles IX, he authorized twenty-four hours of killing. The plan was to eliminate the leaders of the Protestant cause, many of whom had come to Paris for the wedding of Charles’ sister, Margaret, to the Protestant Henry of Navarre. Not counted on was the terrible enmity the strongly Catholic Parisians held for the Protestants. Instead of a day, the carnage lasted for several days and spread out into the countryside. Estimates vary from five to thirty thousand dead.

Into this brewing hellstorm Matthias Tannhauser rides. Carla, noblewoman and renowned player of the viol da gamba, has been summoned to play at a concert for the royal wedding. Though eight months pregnant, she couldn’t bring herself to refuse a royal summons. Tannhauser, away on business in North Africa, has returned to France and ridden to Paris to join his wife. Upon hearing of an assassination attempt on Protestant leader Admiral de Coligny and the consequent cancellation of the musical performance, Tannhauser decides he must find his wife and remove her from a city on the brink of civil collapse. Unfortunately, he has only the slightest idea of where she might be.

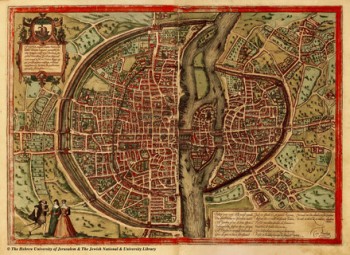

16th century Paris was a maze of streets — some no more than two-meters wide — filled with palaces, churches, and dark, dangerous slums. With no map or guide, Tannhauser is at a loss as to how to find Carla. He acquires the latter when he takes on a stableboy after saving him from a beating. He then sets his sights on finding Carla’s son, Orlandu, a student in Paris. After several misdirections, Tannhauser finds young Orlandu delirious and wounded, with a bullet still inside him. It is clear something deadly involving his loved ones is going on, and Tannhauser realizes he must act with the utmost speed to keep them safe.

During his journey into the bowels of the Louvre, the great fortress in the heart of the city, he receives a clear warning that the city isn’t safe:

“Then hear my counsel. Imagine a nest that is home to a family of vicious and overfed rats, all of whose members harbour secret hatreds for each other. Imagine further that the nest is festooned with webs spun from the purest lies, and that on those webs scuttle venomous spiders almost as big as the rats. Finally, imagine that this nest is located in a pit filled with vipers and poisonous toads.”

The reader learns Carla has been put up with a notable Protestant family, the D’Aubrays. Just as the massacre starts, announced by the ringing of the matins bells of the Church of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, the D’Aubrays’ house comes under assault from a gang of thieves led by Grymonde, a monster known as the Infant of the Cockaigne. The Infant was hired specifically to capture Carla and turn her over to his paymaster. Instead, like Tannhauser before him, he is quickly enchanted by her deep kindness and grace. He takes her to his refuge in a slum called the Yards, the quintessential district that sets its own laws and where no policeman dares go. As for the rest of the household, all, save one daughter, are killed in a frenzy of rape and torture.

For the rest of The Twelve Children of Paris, Tannhauser forges a blood-drenched and viscera-encrusted road across a city taken over by roving packs of Catholic militias bent on scouring every Protestant from existence. Each turn and twist in his road places him against new adversaries, from the aforementioned militiamen to the unseen foes who shot his son and placed a contract on his beloved Carla. Nearly as smart a man as deadly one, Tannhauser begins to put the pieces together to understand what role he and his wife were to play in the night’s hellish affairs.

At the same time a band of children accretes around him, some by chance, others deliberately. Much of the killing he does could be avoided but he is uncompromising in the protection of his young followers. Tannhauser is a savage savior — some great beast raised from the darkest, bloodiest place; protecting his offspring no matter the cost or danger.

Carla, likewise, is forced to move form the relative safety of the Yards accompanied by her own band of children, including her newborn daughter, Amparo. Once wrenched from Grymonde’s sanctuary, she and Tannhauser, unbeknownst to one another, begin a dance around Paris. For one extended period Tannhauser even believes Carla has been slain in the raid on the D’Aubrays. This last drives him to the brink of rage-soaked madness:

“What a terrible loss you have suffered in the service of God and the Crown — “

Tannhauser clenched his teeth. He wanted to stab the priest.

“I serve neither God nor the Crown. I serve no one.”

“I see.” La Fosse stared down at his thumbs.

“I do not even serve any purpose.”

The couple, moving across the death-haunted city, are driven by love. Tannhauser’s love is a ferocious, primal thing that strengthens him to do whatever he must to preserve those he’s chosen to embrace. It enables him to casually allow people to think he’ll let them live before slitting their throats. If it means torturing someone to uncover the next part of the path to Carla, he will. He rarely questions his decision to slay, and has regrets even less often.

Around Carla, nearly the opposite occurs. She becomes the eye of the storm, a place of calm and restoration. A lengthy encounter with Grymonde’s mother, a tarot-reading seeress, activates similar abilities in Carla. Mystical tranquility emanates from her, soothing and restoring her companions, if only to prepare them for the crucible they must eventually enter.

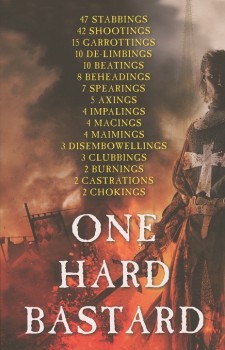

The trek through Paris that will bring Tannhauser and Carla together is orchestrated with a mastery of high melodrama and operatic plot machinations by Willocks. Everything — the dialogue, the narrative, the violence — is cranked up to maximum from almost the first page and never lets up — especially the violence. Unlike the veteran armies of the Great Turk at Malta, few of the opponents facing Tannhauser in The Twelve Children of Paris have more than rudimentary combat skills and he cuts through them with ease, as he does when he storms a tavern where a crime lord holds court:

The villain’s toughs read it best. Their only chance was to draw their daggers and charge. He shot the first in the chest as he rose from his table. The quarrel threw him into the wall like a bag of manure. He used the second tough’s momentum to broach him through the upper gut with the sword, then hammered the ricasso with the stock of the crossbow and carved him open to the bladder on the outstroke. The tough groped at his sundered entrails and reeled away.

Their chief made a dash for the door, or perhaps even for the spontone there propped, but his choice would never be known. Tannhauser chopped him through the hamstrings and sent him down, then ran him through beneath the left rear ribs, perforating kidney and bowel. He left him to squirm and looked at the two hired to brace him from behind.

Paul had wasted his money. They hadn’t moved from their stools. Neither had the three scabs in the corner; nor the gawping courtier whose frolic was proving more lively than he’d bargained for. The sense of panic was intense; yet almost silent as each man weighed his options and found them all wanting.

Tannhauser laid the bloody sword across the counter top.

Paris exists in the most grotesque and hideous detail, from the perverted members of the Ancien Régime that exist in the halls of the Louvre like lice feeding on a dog, to the appalling criminals that hold sway in the slums and back alleys. While mass is celebrated at the front, the back of Notre Dame is where child prostitutes are bought and sold. Fanatacism rules the day on both sides, it’s just that this night Catholics have the upper hand.

Twelve Children is peopled with numerous other characters that will not soon fade from the reader’s mind. Grymonde the criminal, Estelle the rat girl, harelipped Gregoire, and orphaned killer Pascale all rage with life and fire as much as Tannhauser. Even — or especially — the fire-scorched mongrel, Lucifer, caked in human blood, forever pissing on the dead, lingers long after closing the book’s cover.

Tannhauser is a monumental character. As coldly murderous and violent as he is, he manages to remain magnetic and almost noble in the truest sense. The most powerful aspect of Tannhauser is his unbending desire to protect and save those he loves. In The Religion he fought to keep Carla’s son from becoming a killer, and he is forced to repeat the same thing in this book. Tannhauser may not collapse under the weight of his deeds, but he knows others can’t bear them with the same indifference. When Orlandu desires to kill the villain at the center of the plot against his mother, his stepfather holds him back:

“There are many with cause to curse the day I was born,” said Tannhauser. “I need no more cause to remember this one.”

“Won’t it haunt you?”

“If I were the type to be haunted, I would be insane.”

He has seen and done too much to be bothered by it anymore, but he will do whatever he can to keep his loved ones from following his same path.

In a short interview about The Twelve Children of Paris, Willocks said the ultimate theme of the novel is whether love is more powerful than hate.When backed by killing skills like Tannhauser possesses, love clearly is. Seriously, though, it is the question at the heart of the book. Tannhauser is the archetype of paternal love; ready to attack and destroy in order to protect. Carla is maternal love made flesh. It is a love expressed with intimacy, as made clear when she calls the women and girls around her her sisters, something that the power of her love makes more real than any blood connection could ever accomplish.

I have never read as violent a book or one that moves with such unrelenting power. Pain, death, and terror exist on almost every page. It covers only a few hours but is packed with more action and intrigue than would seem possible. It’s like a dozen similar books were distilled down to their basest essence for this one tale. There are times Willocks writes with poetry and light, but they are few and far between. Mostly he writes with a torch or poniard dripping an endless stream of blood. His descriptions of dismemberment and murder are as descriptive as an anatomical guide, never failing to let you know which organ has been spitted or if the victim craps himself. There may have been real beauty in Paris in 1572, but in Willocks’ hands the city is a sewer opening to Hell.

This is the sort of book people love or hate. I love it and hope to see the day Willocks returns with the promised third volume of Tannhauser’s adventures. If you have the slightest aversion to graphic violence this probably isn’t for you. If, on the other hand, you can handle that which would leave most gore-film afficionados shaken, and want to read a brutally exciting story with characters that will burn themselves into your brain, you need to pick up The Twelve Children of Paris. Unfortunately, there’s no e-book in the US to date, so you’ll have to settle for a physical copy.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

Fletcher, have you read Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian?

I’m a big Willocks fan, especially the Tannhauser adventures. I hope a third novel is in the works, one that explores Tannhauser’s Jannissary past. Actually, a prequel novel would be awesome! I generally avoid hyper graphic Grimdark fantasy that wallows in filth and gore. Willocks has such amazing and powerful writing skills that I don’t mind getting bloody and shit splattered while riding along in his Historical adventures. Tim’s gots some skills with wordsmithing…

Brilliant, brilliant novels. Thanks for the review. It’s hard to convey the magnitude of the novel and not scare people off thinking it is violent for violence’s sake. It is not.

Also, Tim had once dropped us a note on the Conan forums. If anyone thought Tannhauser wading through the Massacre unscathed seems unrealistic, he has an interesting justification for that – Tannhauser is a master of martial skills in a city of buffoons, thugs and non-professionals.

http://paulmcnamee.blogspot.com/2013/11/words-from-tannhausers-creator.html

I also eagerly await the third Tannhauser novel.

A masterful review, Fletcher. I’ll simply reiterate that there are levels upon levels of meaning in this novel (as there were in THE RELIGION) which justify numerous rereadings.

As a quick meme to Howard fans, I call it “Conan rescuing his pregnant Zenobia from a Zamora gone mad.” However, it is also Orpheus or Dante fighting his way out of hell. It is THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME meets LES MISERABLES as written by Sam Peckinpah. It is…

With THE RELIGION and THE TWELVE CHILDREN OF PARIS, Willocks has written the two best novels of the 21st century (so far) and too few seem to care. Perhaps that will change.

This is a powerful and beautifully written review that I thoroughly enjoyed. I bought “The Religion” because of your previous review. I’m still reading the book, but yes, your were pretty accurate with your analysis. Willocks knows how to write. The first ever book I read of him was “Green River Rising” many years ago. I was in my early twenties and back then already he impressed me with his uncompromising voice.

@Thomas P. – No, and it’s on my ever increasing TBR stack

@darkman – I hadn’t even thought of Willocks going back in time – that’d be an interesting tale to read

@Paul Mc – You’re welcome, and quite right regarding the nature of the book and the violence that takes up so many of its pages. I had read that line from Willocks last time out, and it’s important to keep in mind when counting the dead in Twelve Children.

@deuce – Thanx, sir! It, and its predecessor, are definitely worth rereading. There are few books I’ve encountered that hit me as hard as these did.

@Woelf – Thank you, sir. I hope you like The Religion. If you do, this one’s even better. I remember seeing Green River Rising when it came out and dismissing it as just another airport book, but based on the Tannhauser books, I owe it a better shot than that.

One could look upon THE RELIGION as Willocks’ Iliad and “Twelve Children” as his Odyssey. Tim Willocks is our Homer, God help us all.

The Religion and The Twelve Children of Paris are my two favorite books. I sure hope the third installment is still coming. I just finished re reading each for a second time and feel and emptiness the size of Mattias or perhaps even Grymonde without more to read. I appreciate your review and wonder if there are any other books you recommend that maybe fit in this genre/world/quality.