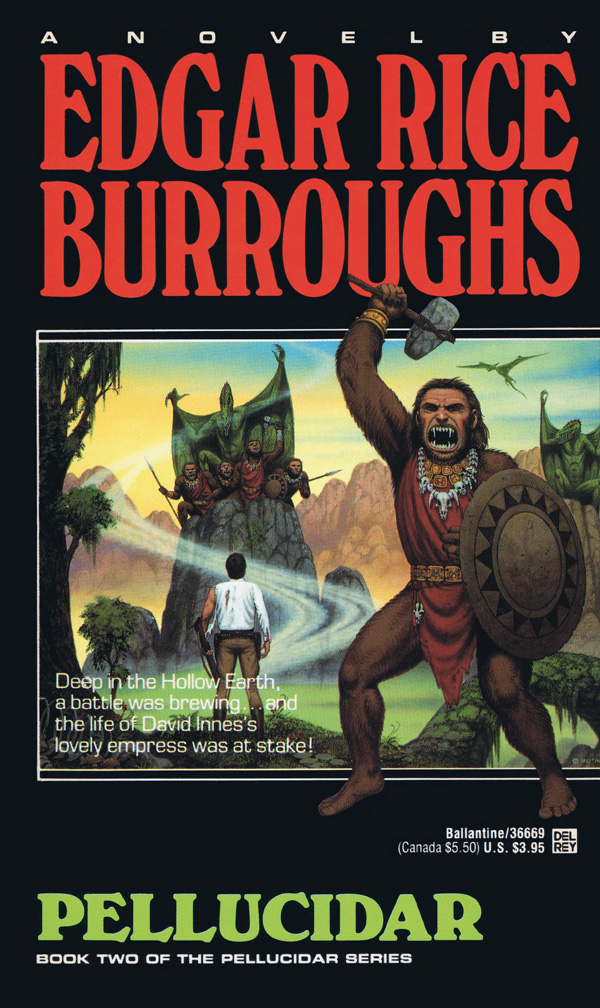

Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar Saga: Pellucidar

Welcome back to the concave world of Pellucidar and the second novel in Edgar Rice Burroughs’s series of adventures within the globe: the eponymous Pellucidar. ERB left readers in suspense about the fate of hero David Innes at the close of At the Earth’s Core, but only a year later delivered audiences from the tension and closed out a duology about the Imperial Conquest of the Pellucidar. (And we still have five more volumes to go after this.)

Welcome back to the concave world of Pellucidar and the second novel in Edgar Rice Burroughs’s series of adventures within the globe: the eponymous Pellucidar. ERB left readers in suspense about the fate of hero David Innes at the close of At the Earth’s Core, but only a year later delivered audiences from the tension and closed out a duology about the Imperial Conquest of the Pellucidar. (And we still have five more volumes to go after this.)

Our Saga: Beneath our feet lies a realm beyond the most vivid daydreams of the fantastic… Pellucidar. A subterranean world formed along the concave curve inside the earth’s crust, surrounding an eternally stationary sun that eliminates the concept of time. A land of savage humanoids, fierce beasts, and reptilian overlords, Pellucidar is the weird stage for adventurers from the topside layer — including a certain Lord Greystoke. The series consists of six novels, one which crosses over with the Tarzan series, plus a volume of linked novellas, published between 1914 and 1963.

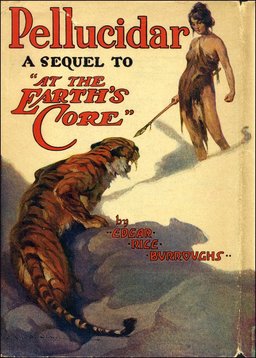

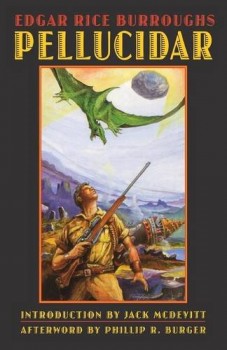

Today’s Installment: Pellucidar (1915)

Previous Installments: At the Earth’s Core (1914)

The Backstory

During the mid-teens, Edgar Rice Burroughs frequently wrote with the aim of creating two-part novels. The books we know today as The Mad King, The Cave Girl, and The Eternal Lover are combinations of an original novel and its closely connected sequel. The Pellucidar series might have gone the same way. The sequel to At the Earth’s Core was written at this time and serves as an immediate follow-up that brings the story of its first novel to a conclusion. If Burroughs hadn’t returned to the setting fourteen years later and continued writing more about Pellucidar, it’s possible that At the Earth’s Core and Pellucidar would be considered a single novel today — probably simply titled At the Earth’s Core. (My title choice would be Conquest of the Earth’s Core.)

Burroughs started writing Pellucidar in Chicago after an extended trip to California, beginning in November 1914 and finishing in January. It was a crowded period, since ERB was busy trying to expand his new fiction empire by negotiating movie deals, none of which went far at first. Pellucidar initially appeared in four installments in All-Story Cavalier Weekly in May 1915. The first book edition was published by A. C. McClurg in 1923.

The Story

The Story

When the previous book concluded, David Innes had vanished into the Sahara to find the Iron Mole and drill back to Pellucidar with tons of technological goodies to take the war hard against the Mahar masters. However, the fictional Edgar Rice Burroughs has heard nothing from him since.

While pseudo-ERB is planning his next hunting expedition to Africa (a place where the real ERB never set foot), he receives a letter from Cogdon Nestor, a man who read At the Earth’s Core — and didn’t like it. But his letter isn’t a complaint about Burroughs’s writing skills. Nestor has discovered what appears to be Innes’s telegraph device buried in the Sahara. Pseudo-ERB confirms that the published story is true and races to the location. Via the telegraph, David Innes sends his tale of the inner world to the surface world…

With the help of an Arab tribe, David Innes gets the Iron Mole into position to bore back to Pellucidar, taking the captive Mahar with him. Upon breaking through to Pellucidar, the Mahar flies off to freedom and Innes starts trying to figure out where he’s emerged in the inner world. Setting out to locate the land of Sari and his ally Ghak, Innes runs straight into his inventor pal Abner Perry. Perry brings bad news: the alliance of tribes Innes forged before returning topside has collapsed, and Innes’s love Dian the Beautiful has vanished.

With the “reset button” essentially hit for Pellucidar (the Mahars have even regained their Great Secret, thanks to that piece of crud Hooja the Sly One), David Innes and Abner Perry have a gargantuan task ahead of them trying to assemble the Federated Kingdoms of the Empire of Pellucidar. Perry puts his attention on the devices brought in the Iron Mole while Innes makes expeditions to either find Dian or meet up with the various tribes (sometimes both). He picks up a valuable new ally on the journey to the Land of Awful Shadow and the tribe of the Thurians: Raja, a loyal wolf-hound (hyaenodon). Raja’s mate Ranee shows up later to join the adventuring.

Innes sails to an island where Hooja leads a band of Sagoths in the service of the Mahars. With the assistance of the gorilla-sheep people of Gr-gr-gr, Innes frees Dian from Hooja’s prison. Hooja pursues them on the seas, but ends up in a massive naval battle with Abner Perry’s newly minted fleet. With Hooja’s cutthroats crushed and Perry’s well-armed Pellucidarian force at his call, David Innes begins an extended assault on the cities of the Mahars. Perhaps he can realize his dream of a modern Empire of Pellucidar after all. With sewing machines and typewriters and everything!

The Positives

The Positives

As a direct continuation of the action and setting of the previous novel, Pellucidar is a success. Readers looking for further adventures in a strange prehistoric land and answers to the questions left at the end of At the Earth’s Core won’t come away feeling slighted. Pellucidar even delivers a few surprises on the journey, like Raja the Wonder Hyaenodon and Tul-al-sa the Open-Minded Mahar.

Although At the Earth’s Core is definitely the superior of the two books, one place where Pellucidar nudges ahead is in characterizations, particularly of David Innes. The deepening of the characters somewhat makes up for the inevitable lack of the thrill of discovery any second installment can suffer. David Innes is no longer a wanderer trying to survive or rescue the woman he loves. He’s turning into a colonial empire-builder. At first he’s jocular about the idea of the Federated Kingdoms of the Empire of Pellucidar with himself crowned as David the First. But he soon starts taking it seriously as a goal even more important than Dian.

Innes dreams big: “With such as these I could conquer a world. With such as these I would conquer one!” Even though he claims the emancipation of the Pellucidarians is the reason to create the empire, there’s no denying Innes’s own aggrandizement is what really drives him. But this is what makes Innes an interesting hero: he isn’t John Carter, who’s far more powerful than everyone else around him. Innes only has the advantages of ambition and access to better technology — the latter of which does little good since he keeps losing it. David Innes has the psychology of a budding megalomaniac, but also flashes of a humanitarian reformer. He’s an embodiment of the “benign imperialism” that was on the minds of many in the U.S. during this period.

The culmination of Innes’s imperialism and humanity comes in his speech to Perry after the end of the grand naval battle. As they look forward to the next step, Perry pushes for forging more marvelous weapons; but Innes urges they instead make the tools that are the true “best” their world can offer:

“…sewing machines instead of battle-ships, harvesters of crops instead of harvesters of men, plowshares and telephones, schools and colleges, printing-presses and paper! When our merchant marine shall ply the great Pellucidarian seas, and cargoes of silks and typewriters and books shall forge their ways where only hideous saurians have held sway since time began!”

I love that the sewing machine is the first positive invention that pops in Innes’s head. He must be tired of wolfskins.

The best character moment for Innes is at the opening. The arrival at Pellucidar leads into an amazing sequence with his Mahar prisoner, Tul-al-sa. Innes feels for the Mahar as a thinking creature with a culture, holding the same role in her world that humans do in the upper world. He empathizes with how she must struggle with the way her worldview has dramatically overturned because of the visit to the surface, where the sun moves and the land cuts off at the horizon. The Mahars were already astonishing enough in At the Earth’s Core, and now ERB adds another dimension to them by peeling away their monstrousness to emphasize their sentience. As Innes observes, they are in their own way “an enlightened race.” It’s a flipped version of the horrific Mahar temple scene from the previous book; as captivating as that sequence, but for the opposite reason. That all this thought comes from a hero who sets out to destroy the Mahars makes it even more intriguing.

The best character moment for Innes is at the opening. The arrival at Pellucidar leads into an amazing sequence with his Mahar prisoner, Tul-al-sa. Innes feels for the Mahar as a thinking creature with a culture, holding the same role in her world that humans do in the upper world. He empathizes with how she must struggle with the way her worldview has dramatically overturned because of the visit to the surface, where the sun moves and the land cuts off at the horizon. The Mahars were already astonishing enough in At the Earth’s Core, and now ERB adds another dimension to them by peeling away their monstrousness to emphasize their sentience. As Innes observes, they are in their own way “an enlightened race.” It’s a flipped version of the horrific Mahar temple scene from the previous book; as captivating as that sequence, but for the opposite reason. That all this thought comes from a hero who sets out to destroy the Mahars makes it even more intriguing.

Thankfully, Burroughs provides a payoff with Tul-al-sa when she later intervenes to save Innes from his fate in the arena. One of the complaints I often have about ERB’s plots in his later books is how often he discards ideas that could prove useful. Here, he’s focused on weaving together a cohesive tale.

Many of the other superlative scenes center on Raja, the Woola of Pellucidar. Raja expands Innes as a sympathetic figure — here’s a fellow who loves dogs and goes out his way to rescue a drowning one — and gives him more to do during the periods he’s away from the supporting characters. Animal sidekicks exist for a reason: they give writers greater freedom and possibilities, and ERB makes the best use of the wolf-hound pair. The chase scene where Raja and Ranee help Innes rescue Dian from a Thurian mounted on a lidi [wait, what the hell did I just write?] is one of the action highlights.

There’s more time spent with Perry here than in At the Earth’s Core, and he’s a more peculiar character than the conventional old professor type. Now he’s spouting daft ideas, such as his rocksteady belief that anything humans have invented once before can be invented again, even by someone with absolutely no knowledge of the field. This leads to the great boat-building scene, where Perry fiddles around with jerry-rigging a boat and attaching grand “Imperial Navy” notions to his haphazard contraption. If Burroughs wrote this later in his career, it would be an interminable and unfunny read. Here it just puts a smile on my face. Perry also names Hooja’s followers “Hoosiers” and officially bequeaths the name “Indiana” on their island. Good contemporary comedy to leaven the otherworldliness.

Burroughs’s writing is funnier in general this go-round. David Innes has comic self-deprecating moments when he uses his imperial title in contrast to less-than-imperial actions, such as bungling through a prison wall to reach Dian: “I doubt if any other potentate in a world’s history ever made a more undignified entrance.” Here’s another of Innes’s fine ironic bits about the potential of empire:

Seeing that they were determined to give battle, I leaned over the rail of the Sari and brought the imperial battle squadron of the Emperor of Pellucidar into action for the first time in the history of the world. In other and simpler words, I fired my revolver at the nearest canoe.

The pendent world and the Land of Awful Shadow are the book’s major new ideas. The Land of Awful Shadow is unfortunately nothing special once Innes reaches it, but the pendent world is fascinating. There’s immense promise in this rotating mini-world locked in place between the central sun and the concave ground. Innes recognizes it as a potential tool to create a time-keeping method in Pellucidar.

The pendent world and the Land of Awful Shadow are the book’s major new ideas. The Land of Awful Shadow is unfortunately nothing special once Innes reaches it, but the pendent world is fascinating. There’s immense promise in this rotating mini-world locked in place between the central sun and the concave ground. Innes recognizes it as a potential tool to create a time-keeping method in Pellucidar.

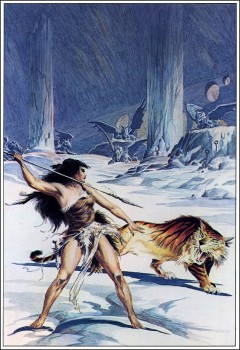

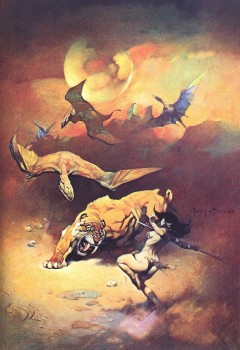

Despite the arsenal Innes brings with him, Burroughs makes sure to hold his hero back from dominating everything with modern gunfire. Innes remains an underdog even with pistols and rifles, such as in the exciting arena fight with a tarag, where a pistol can only do so much against the muscular mass of a sabertooth cat. Innes loses his weapons occasionally, but in logical ways that don’t make readers groan at the timing. Who needs a repeating rifle when they have two hyaenodon attack dogs as pets?

The chrono-distortion of Pellucidar has gotten even stranger. David Innes wisely brings a watch with him so he can keep track of time in the land of eternal noon. But within only a few paragraphs the watch breaks — as if a force inherent in the land is antagonistic toward time’s measurement. Perry and Innes at one point sleep and have evidence from the growth of nearby plants that they were unconscious for a month. That seems impossible, but the bizarreness of this concept is part of why ERB’s work lives on. The distortion also permits a neat plot cheat, where Perry can design a full navy and an alliance of millions of Mezops during Innes’s short set of adventures with Juag, Dian, and dog pals.

The frame story is one of the finest that ERB used to add verisimilitude. The highlight is the punch in the nose Burroughs gives himself when Cogdon Nestor insults his writing: “I became interested in your story, At the Earth’s Core, not so much because of the probability of the tale as of a great and abiding wonder that people should be paid money for writing such impossible trash.” But then Nestor begs Burroughs to tell him that story is mere fiction. Pseudo-ERB replies with a blunt, and sort of amazing, two-word reply: “Story true.” It’s a terrific way to hurl readers into the sequel with renewed excitement.

The Negatives

The second Pellucidar novel maintains the pace, but stumbles in an important way: it doesn’t expand the world enough. Burroughs varies the action, such as the snow-bound mountain trek and the climactic naval combat, but much of the story remains constrained within familiar stomping grounds, identical foes, and the same supporting cast.

Nowhere is this easier to pick up on than in the squandering of the Land of Awful Shadow. There are almost no distinguishing features or bizarre fauna for a location with such a great name and potential. It’s easy to forget that Innes is even in the Land of Awful Shadow for much of this section of the book, with the exception of mention of the pendent world. There’s a disappointing lack of fantastic creatures elsewhere in Pellucidar; the fauna seems to have shrunk down to elk, cave bears, tigers, and only the occasional mention of dinosaurs and oddities like dyryths that were a key part of the fun of At the Earth’s Core.

Nowhere is this easier to pick up on than in the squandering of the Land of Awful Shadow. There are almost no distinguishing features or bizarre fauna for a location with such a great name and potential. It’s easy to forget that Innes is even in the Land of Awful Shadow for much of this section of the book, with the exception of mention of the pendent world. There’s a disappointing lack of fantastic creatures elsewhere in Pellucidar; the fauna seems to have shrunk down to elk, cave bears, tigers, and only the occasional mention of dinosaurs and oddities like dyryths that were a key part of the fun of At the Earth’s Core.

Let’s talk about that ending, because even though Pellucidar features a rattler of an action finale — the naval war between Perry’s fleet and Hooja’s — the actual wrap-up is a bungle. As with At the Earth’s Core, Burroughs switches the style into a fast synopsis of military action against the Mahars. Then he finishes with a hastily created utopia that Innes and Perry construct out of seemingly nothing. (We could credit it to Pellucidar’s timelessness; maybe Perry and Innes had twenty years to master every science available in the early twentieth century.)

It’s not the implausibility of the technological marvels that’s the problem; implausibility is baked-in to Burroughs’s work and is one of its appeals. The problem is that Burroughs cheated himself out a of a potential trilogy that would’ve been even better than this duology. I realized during this reading that the Pellucidar series should’ve opened with a three-novel sequence the way the Barsoom series did. The last chapter of Pellucidar is the outline of what could’ve been the third novel: Innes’s allied tribes engaged in a final gunpowder war against the Mahars and the struggle to build a new society in a Stone Age world with the equipment on hand.

There’s great potential in juxtaposing the Steam Age with the Stone Age; the most memorable image of the closing pages is Innes dreaming of a locomotive rattling through a jungle past sabertooth cats and mastodons. But this is material for that nonexistent third part of a trilogy. I think ERB missed a great opportunity here.

Fashioning an Empire of Pellucidar as a utopian simulacrum of industrialized society feels as if it betrays why Pellucidar is interesting in the first place. If this were caustic satire, à la A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, this ploy may have worked. But it fits poorly with this type of science-fantasy adventure. A comparison to the Martian novels is again worthwhile: John Carter brought victory to Barsoom in The Warlord of Mars through unification, not through radically remaking the planet to fit his ideas. Carter preferred Barsoom — as do readers, at least when they’re reading his adventures. By industrializing Pellucidar, David Innes makes it dull. We like Pellucidar and its whacked out chrono-distortion, super-lizard rulers, odd beasts, and primitive cave-men civilizations.

Short version: David Innes took the best part of a theme park — the one with robotic dinosaurs and roller coasters — and redesigned it as Main Street U.S.A. You know, the dullest part of Disneyland. At least this waits to happen until the end so it doesn’t ruin the enjoyment of the rest of the story. The place where the Pellucidar duology halts is too rosy. It feels as hollow as — well, as ERB’s Earth.

The “reset button effect” at the beginning is a tad annoying: David Innes learns that all the progress he left behind has been erased, and he’s back to square one in the fight against the Mahars. Dian is missing again, and Hooja the Sly One is at liberty. The great secret of Mahar reproduction, which was the lynchpin of the previous book, ends up back in the Mahars’ possession and then is simply forgotten.

The “reset button effect” at the beginning is a tad annoying: David Innes learns that all the progress he left behind has been erased, and he’s back to square one in the fight against the Mahars. Dian is missing again, and Hooja the Sly One is at liberty. The great secret of Mahar reproduction, which was the lynchpin of the previous book, ends up back in the Mahars’ possession and then is simply forgotten.

Abner Perry is great for humor, but I wish he stuck around for the middle section. He’s ultimately more responsible for the Empire of Pellucidar than Innes, since he spent time forging the Mezops into a labor force that created metallurgy and fashioned an armada while Innes was hunting for Dian and failing at diplomacy. Perry does better than poor Hooja, who sidles off into nowhere during the otherwise great finale. He deserved a bigger villain send-off.

Dian is mostly useless as a character, and even as a motivator she isn’t that important. She’s usually located in a spot that Innes needs to visit anyway. Although the Thurian who seizes Dian during the thag hunt leads to one of the more exciting action bits, where Raja and Ranee really pull their weight, it’s an out-of-the-blue kidnapping that reduces most of Dian’s potential effectiveness. David Innes praises her bravery, but she’s minor compared to tougher ERB heroines like Jane Porter and Tavia in A Fighting Man of Mars.

Burroughs relied on coincidences a bit too often, and oh dear he hurls out a few zany ones here. The first person David Innes runs into in the millions of square miles of Pellucidar is Abner Perry — the exact person he was looking for! Amazing! Then the Mahars stick Innes in the arena with none other than Dian — the exact person he was looking for! Astounding! When Innes reaches the entrance to Hooja’s cave-prison, he immediately runs into an escaped prisoner who knows exactly where Dian is held! Wow! I wish Burroughs found better ways to manage events rather than through plot magic, which undermines Innes’s heroism and basic investigative skills.

I don’t usually break out of continuity when looking at an ERB series and mention something from a later book, but I must bring this up: despite the promise of the pendent world, none of the Pellucidar adventures ever go there.

Craziest Bit of Burroughsian Writing: “I have never been much of a runner; I hate running. But if ever a sprinter broke into smithereens all world’s records it was that day when I fled before those hideous beasts along the narrow spit of rocky cliff between two narrow fiords toward the Sojar Az.” By the way, one of the hideous beasts turns out to be Raja.

Most Inventive Idea: The pendent world that hovers between the sun of Pellucidar and the Land of Awful Shadow. Too bad we’re never getting there!

Best Creature: The sheep-gorilla people of Gr-gr-gr.

Carson Napier Pre-Memorial Foolishness Award: David Innes should learn not to sleep out in the open when any nap might last a month — plenty of time to have his weapons stolen.

So much for the planning: Innes brings a watch to Pellucidar to counter the effect of its eternal noon. The watch promptly breaks. Sorry, nobody gets to overcome ERB’s concept of timelessness.

How about a sequel? The story has reached a definite conclusion, even with the Mahars still in existence somewhere. But you know what? I want to see Innes’s new paradise wrecked somehow, so bring that on. If there isn’t a third installment in a trilogy, at least make Pellucidar wilder once again in the next book. I don’t want to hear about postal reform in Amoz, is what I’m saying.

Next: A brief historical digression into the strangest hollow earth theory, and then Tanar of Pellucidar.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Godzilla on interviews.

I wonder if the impatience you feel about the impact of sewing machines on Pellucidar is also a more contemporary reluctance to impose western civilization on “primitive peoples”. I agree that the modernization programme that Perry and Innes propose is irritating because what the reader wants is monsters and proper fighting. However, a part of me feels revulsion at the idea that Pellucidar will benefit from all the fine consumer goods that they will be showered with. It is also in direct contrast to Tarzan’s underlying belief that civilization is not a good thing and that the “savages” of the jungle are far superior to the western tourists who pass through. I don’t think that Burroughs had a view either way – at least not one that underlies all his fiction. I can’t help feeling that, in this case, Tarzan’s viewpoint seems the less intrusive. Neil

@Neil – ERB did not have a consistent underlying theme regarding this. As you point out, Tarzan’s idea of civilization is on the opposite side of Innes’s. (And that Tarzan crosses into Pellucidar later is fascinating, which is a way of saying that I’m going to be dealing with this conflict in more depth when I get to Tarzan at the Earth’s Core.) Burroughs had great flexibility in his story themes in the first part of his career, and that was because he often went with his gut instinct at the moment. He later tends to fall into patterns, but at this early stage he was far more mercurial.

A good example is The Land That Time Forgot, which deals with biological and technology advancement, and in this case ERB doesn’t take a specific stance toward it, only accept it as something all organisms strive for. However, there is an aberration at the upper end, the wieroos.

Ultimately, my dislike of the impact of Innes’s 20th-century upgrades isn’t from a modern reluctance to colonial attudes. It’s simply that I like Burroughs’s worlds to remain wild because he tells better stories in these settings. He wasn’t adept at city settings, as he showed with Carson of Venus. When he concludes something like Pellucidar with a modern city, it feels like he’s closing off more story avenues. But I’ll also admit I’m using foreknowledge that there will be more Pellucidar stories. I make an effort to position myself in the time that each book was published, but historical knowledge is impossible to block entirely, something I accept as it comes.

Anyway, there are good ideas to ponder here, and that will make Tarzan at the Earth’s Core all the more enjoyable to read.

I’m a little confused by how you’re not happy that this book wasn’t split into 2, as you put it it could then be a trilogy. But there are 7 books in this series. Also I see in the comment above that a lot of folks don’t like the western culture pushed in, and in a way I do prefer how Tarzan sees the world, but also when you got these 2 guys who came from an advanced civilization now being thrust into the wild and trying to protect a new people it’s only to be expected that they’ll want to bring a bit of their world back to life there. But there were some things that didn’t work as well. Like how they tried to bring clocks into the mix, but the people hated them so much that they got rid of them. So not everything does stick around. Granted it has been years since I read this series.

Reading these Pellucidar posts has prompted me to read up on hollow earth theories. I think the Symmes theory is my favorite. Personally, I’ve always known in my heart that the earth can’t just be rock and molten rock all the way through. There *must* be prehistoric monsters, fungus forests, or *something*. Sadly, Burroughs’ proposal is invalidated by the shell theorem of classical mechanics, which tells us that everything in Pellucidar would promptly fall into that sun of theirs.

@Raphael – I’m going to be doing a whole post on one of the oddest of all hollow earth theories in a tie-in post before doing Tanar of Pellucidar, the Cellular Cosmogony theory of Cyrus Teed. (The world is hollow, but we’re already living on the inside!)

Excellent review as always, Ryan. Keep getting the good word out.

I agree that a “Pellucidar Trilogy” would’ve been best (maybe more Mahars!). ERB didn’t always go as deep as he should’ve with some of his wondrous concepts. THE MONSTER MEN and BEYOND THIRTY come to mind. Still cracking good reads!

I’ll also point out that ERB did pull off a bit of a trilogy (not unlike his Caspak novels) with the Tarzan/Tanar/Von Horst run.

@deuce – The Mahars did need a better “showdown” than they got as Pellucidar quickly wrapped up. I would’ve loved to see Tul-al-sa return as well, possibly as a negotiator between worlds. I like what Burroughs does with Tul-al-sa, but there was even more that could’ve been done with her.

A fine conclusion to At the Earth’s Core but not as good though the naval battle sequence at the end is awesome.