Modular: How to Introduce Kids to Tabletop Role-Playing #2: Actually GMing Kids

GMing for kids (read part 1) is pretty much like GMing for adults ; almost too much like.

Kids — especially geeky ones — don’t evolve into adulthood in a linear way. A 10-year-old can be like a 15-year-old and a 9-year-old sharing the same brain (and same bedroom, as Warhammer figures jostle with Lego). It’s very easy to GM to their more grown-up aspects and forget their younger ones, which can then throw a spanner in the works.

Obviously, it all depends on the kids and your relationship with them. However, here’s what I’ve learned…

Kids Are Surprisingly (No, Really) Comfortable With Bad Language and Violence

Geeky kids are usually quite — sometimes alarmingly — comfortable with bad language and violence (because YouTube and video games); it’s the parents that are the potential problem.

If you are also a parent or used to playing with children, then you probably already have the knack of being in flow and yet age appropriate. If not, then it’s probably worth establishing what the comfort zones are, or stating your own performance limits.

If you are GMing at a con and not specifically for kids, then it’s entirely reasonable to warn parents that there’ll be bad language and violence; the parents probably already know that. (Conversely, one way of getting early teens into an adult game at a convention is to reassure the GM that the kids in question are Halo players and that it’s OK to swear in front of them — the GM’s main concern will then be whether your kids know how to play.)

You also have to set expectations: specify conduct at the table — insist that mobile devices go away — and also state expected moral compass during the game, otherwise you may have a gang of Angry Birds-playing murder hobos on your hands which makes for a boring session and possible real-world repercussions as the stories leak out about how they spent the afternoon playing at setting light to orphans while robbing widows.

However, Kids Deal Poorly With Emotional Violence

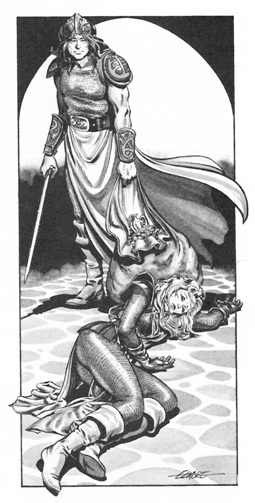

Kids are used to playing at physical violence, and even — thanks, to series like Horrible Histories — can sometimes take a ghoulish relish in consequences. They don’t however deal well with emotional violence or tragedy, especially if they are at fault.

I read online about a kid brother being upset when he used magic to turn an evil wizard into a friend so the rest of the party could take him out. The wizard’s dying words were, “But I thought we were buddies! Why aren’t you helping me. Argh… etc.”

Don’t do this.

Nor should you suddenly humanize a guard they’ve just knifed and have him weep about the fate of his fatherless children as he expires.

I find the best solution is twofold.

First, be strict about enforcing alignment (or character moral compass): “You can’t kill the guard, he’s just doing his job/it isn’t chivalrous. However, you can try to knock him out.”

Second, fall back on narrative summary: “The guard falls dead. You don’t feel good about it…” Or, “The guard screams as he dies. The place erupts with soldiers…”

Kids Like Tracking Money and Experience

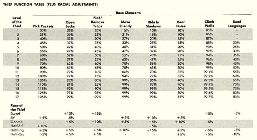

This surprised me. My first instinct was to gloss over money and to not bother with experience. However, whereas most adult gamers appreciate that neither money nor experience are story, and that the latter is just a necessary abstraction that breaks the fourth wall, kids love both to shop and to keep score.

Kids seem to enjoy the sense of empowerment from having an imaginary budget to spend, and take the reality of the game seriously enough to care about shopping for weapons and kit. Conversely — from video games — they are very used to having numbers to track their progress outside the reality of the game.

Kids Need Clear Objectives

Most adult players don’t enjoy spending an hour wandering around looking for the adventure! Kids being new to the game will have less patience than their older counterparts. Even in sandbox games, they need to have a sense of purpose such as, “Earn enough money to buy better armor” — the Fate system is particularly good for generating character-driven objectives.

Kids are also not familiar with all the genre conventions. This makes them great fun to GM — everything is fresh — but also sometimes hard to nudge in the right direction. For example, they may — quite rationally — decide that going down a dungeon is far too dangerous an idea! This can be a good thing, making you work harder to establish motivations. However, if derails the game, it’s OK to say, “This is what the game’s about.”

Kids Emotionally Over-Invest in Their Characters

Short version: Kids may cry if you kill their character.

Long version: Because they identify with their character, kids may become too risk-averse and then too emotionally involved for the game to be fun.

There’s no right way to get around this one because the more you dilute the sense of threat, the more you risk wrecking suspension of disbelief. I tend to be open about nobody dying unless they do something stupid, but then keep the focus on the mission, which they can fail to complete.

Kids Are Still Kids

Though the munchkins at your table may behave remarkably like college-age players — bickering over loot, blundering into traps, going on the rampage when they can — they are still actual children. They need snacks, drinks and restroom breaks — both of which they will forget — and breaks to run around — trampolines and Nerf guns are good.

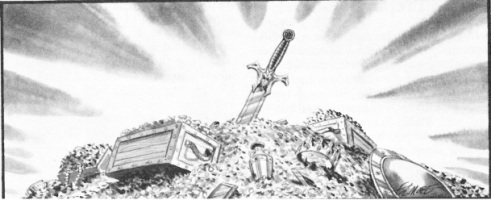

All that said, roleplaying with kids isn’t that much different from playing with adults. The first game I GM’d for my son and his 9-year-old-friends, they had wild time raiding my dungeon, solving traps, and fighting denizens. They survived by the skin of their teeth and only just managed to carry away the Arrow of Smiting (because it was stuck in the thief).

What’s not to like?

M Harold Page is the Scottish author of works such as Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”) NOW AVAILABLE IN OMNIBUS EDITION! For his take on writing, read Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)

A husband and wife are in my current S&W game (four total players). They want to add their 14 year old daughter. So there’s now a thirty-plus year age span in the group (and I’m 49).

There are a couple different levels (game play and personal) I’m sorting through at this mix of adults and a young teen.