Fantasia 2016, Day 20: Twisting History and Twice-Told Tales (The Arbalest and The Piper)

Tuesday, August 2, was the next-to-last day of the 2016 Fantasia festival. I had two movies lined up. First would come The Arbalest, at the De Sève Theatre: a period fantasy about a man who made an addictive puzzle in a slightly alternate 1970s. That would be followed by The Piper (Sonmin), a Korean film that reimagined the Pied Piper story as set in a postwar Korean village. Both looked promising. One delivered on that promise.

Tuesday, August 2, was the next-to-last day of the 2016 Fantasia festival. I had two movies lined up. First would come The Arbalest, at the De Sève Theatre: a period fantasy about a man who made an addictive puzzle in a slightly alternate 1970s. That would be followed by The Piper (Sonmin), a Korean film that reimagined the Pied Piper story as set in a postwar Korean village. Both looked promising. One delivered on that promise.

The Arbalest is the debut feature by writer/director Adam Pinney, presenting the career of millionaire toy inventor Foster Kalt (Mike Brune). In the late 1970s the reclusive Kalt prepares to tell the story of his life to a TV news crew. He reveals less to them than one might expect, but we see flashbacks to his past; specifically, to the eve of a crucial toy fair, when Kalt spends a fateful night in a hotel room with two other people. One of them, an unnamed man (Jon Briddell), is the real inventor of the Kalt Kube, the toy Kalt would go on to present as his own. The other is a woman named Sylvia (Tallie Medel), with whom Kalt falls madly in love. Further flashbacks show us Kalt stalking Sylvia, taking a cottage near her home, and entering into conflict with her and her husband (Robert Walker Branchaud).

The Arbalest is a difficult movie to figure out, though on a basic plot level what’s happening and why is always clear. Movement between different time periods is smooth and assured. But what we’re watching is increasingly baffling, both in terms of character development and of the world we think we’re seeing.

The dialogue’s mostly acceptable, if occasionally failing to be clever, and never creating a sense of period. But the transition between events, between structural units, is often baffling. Chronologically, Kalt begins the film as an affectless ingenue (in fact impaired enough in his interaction with the world around him I began to wonder if he was meant to be slightly autistic). Success changes him, and in the second set of flashbacks his grip on sanity has become even more tenuous; visually he now recalls Hunter S. Thompson, though this may be a coincidence as there’s no reference I could see to Thompson’s life or work. Finally, a few years later, when the TV crew arrives to interview Kalt, he’s a withdrawn wreck. It is easy to imagine how the transition from one phase to another happened. But the script is unconvincing, and I don’t think Brune’s performance anchors the diverse stages of the character’s life. The result is a random, disconnected film.

There is a through-line, in which we follow Kalt’s increasingly obsessive love for Sylvia and its consequences, but that through-line feels insufficient to tie the movie together. The relationship becomes something on which to hang bits: bits of performance, bits of framing, bits of dramatic moments. It doesn’t cohere into something of interest in itself. For me, at least, there was no feeling of unity — for all that the retrospective frame-structure of the interview ought to impose that sort of a unity on the material.

Theoretically, that lack of character ought to be fatal to the film, and most of the time I think it is. But I have to wonder if there’s another level that didn’t come across to me, and that’s a function of the movie’s world. The young Kalt goes to a toy convention with a gadget he hopes will make his fortune, only for Sylvia and the man in a suit with her to tell him it’s a lousy toy. The odd thing is that the gadget’s a device that turns oxygen into helium. Which is to say, it’s not a toy or a gadget, but a major invention. Much later, at the climax of the film, Kalt invents something that’s relatively commonplace in real life but apparently unheard of to the other characters in the film. It also ought to be something impossible for him to throw together in the time he had and with the materials he had, so far as I can tell. So what’s happening?

Theoretically, that lack of character ought to be fatal to the film, and most of the time I think it is. But I have to wonder if there’s another level that didn’t come across to me, and that’s a function of the movie’s world. The young Kalt goes to a toy convention with a gadget he hopes will make his fortune, only for Sylvia and the man in a suit with her to tell him it’s a lousy toy. The odd thing is that the gadget’s a device that turns oxygen into helium. Which is to say, it’s not a toy or a gadget, but a major invention. Much later, at the climax of the film, Kalt invents something that’s relatively commonplace in real life but apparently unheard of to the other characters in the film. It also ought to be something impossible for him to throw together in the time he had and with the materials he had, so far as I can tell. So what’s happening?

We’re shown the level of fame Kalt achieves through his inventions, and it’s clear from the start that we’re looking at an alternate past that didn’t unfold quite the way ours did. So is it even more of an alternate reality than it appears, perhaps one with its own laws of physics? Or — is much of the film simply a delusion? Is more of it than it seems happening inside Kalt’s head?

Well, maybe, but if so it’s hard to see where the hallucinatory aspect departs from reality; where the delusions begin and why. And hard to see why Kalt has these particular delusions. Imagining the film as a story Kalt tells himself is tempting, and looks like it might hold the key to his character, but I can’t see that it’s actually enlightening. It raises questions about what sort of a reality we’re seeing without providing any obvious answers about Kalt or who he is.

But then again, this is a movie about games and puzzles. The arbalest of the title isn’t the medieval weapon of war, but (it turns out) a board-game in this alternate reality; a game named for the weapon. One might note a distant connection between the idea of the arbalest and the final invention Kalt creates. But again the connection feels rudimentary, as though material was there for a symbolic point but execution is lacking. The point I want to make: the movie’s named for a game, while Kalt’s story is about building puzzles; games again. But what does that add up to? Do the way people play games reveal their personalities? Possibly, possibly not. Once again, I find there are interesting hints that don’t develop in any immediately obvious way.

But then again, this is a movie about games and puzzles. The arbalest of the title isn’t the medieval weapon of war, but (it turns out) a board-game in this alternate reality; a game named for the weapon. One might note a distant connection between the idea of the arbalest and the final invention Kalt creates. But again the connection feels rudimentary, as though material was there for a symbolic point but execution is lacking. The point I want to make: the movie’s named for a game, while Kalt’s story is about building puzzles; games again. But what does that add up to? Do the way people play games reveal their personalities? Possibly, possibly not. Once again, I find there are interesting hints that don’t develop in any immediately obvious way.

There’s clearly a considerable amount of craft involved in The Arbalest. It’s visually striking, with excellent production design evoking the movie’s different eras in set furnishing, costume, even colour sense. That said, it makes a very small world (presumably in part a function of the movie’s budget); a few rooms, more or less. There’s a sense of a glittering perfect surface that is, if not lacking in depth, more of a miniature than a full-sized portrait.

I’d like to find a way to make the movie work, but the way it’s put together it feels almost willfully scattershot. The toys in the early scenes are associated with magic in dialogue; is this relevant? I don’t know. Does the kind of alchemical transfiguration Kalt seems to have created connect up to those stray lines? Again, I don’t know. Are we meant, in the final scenes, to question what is a toy and what is not? Again: well, maybe.

In the end I have to say that the movie’s surrealism is too erratic to work. The logic, or the logic behind the lack of logic, is unclear. The Arbalest may be about toys, but one can say that the film itself is a kind of toy: it’s a puzzle with a beguiling surface, but less behind it than you’d like.

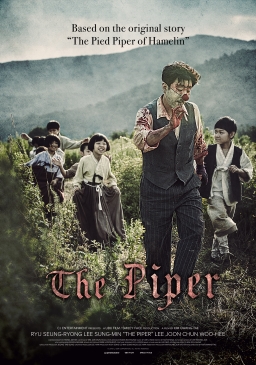

I headed across the street after The Arbalest to watch writer-director Kim Kwang-tae’s The Piper, a horror-oriented retelling of the Pied Piper story. Set in Korea after the war, it follows a musician and father (Ryu Seung-ryong) travelling through the countryside with his young son Yeong-nam (Goo Seung-Hyeon) to reach what he thinks will be medical help for the boy, who suffers from tuberculosis. On their way, they come to a strange secluded village. The villagers might be able to help Yeong-nam, and the desperate father strikes a deal to rid the village of the rats plaguing it in exchange for curing his son. But the village leader (Lee Sung-min) isn’t happy, and plots to betray the piper — who, meanwhile, is drawing closer to the mysterious shaman Mi-sook (Chun Woo-hee, who played the title role in the remarkable Han Gong-ju).

I headed across the street after The Arbalest to watch writer-director Kim Kwang-tae’s The Piper, a horror-oriented retelling of the Pied Piper story. Set in Korea after the war, it follows a musician and father (Ryu Seung-ryong) travelling through the countryside with his young son Yeong-nam (Goo Seung-Hyeon) to reach what he thinks will be medical help for the boy, who suffers from tuberculosis. On their way, they come to a strange secluded village. The villagers might be able to help Yeong-nam, and the desperate father strikes a deal to rid the village of the rats plaguing it in exchange for curing his son. But the village leader (Lee Sung-min) isn’t happy, and plots to betray the piper — who, meanwhile, is drawing closer to the mysterious shaman Mi-sook (Chun Woo-hee, who played the title role in the remarkable Han Gong-ju).

It’s a more complex story than the original tale, necessarily with deeper characters. Perhaps the most notable changes are the way one’s sympathies are neatly inverted. In the traditional legend the Pied Piper is a mysterious supernatural figure who toys with an everyday village. Here we sympathise with the piper, a father trying to do what’s best for his child, while the village is made mysterious, cursed long before the piper arrives on the scene.

That said, all the darkness of the legend is preserved, though the plot unfolds with several intelligent revisions. The story isn’t the original version, not quite, but is very conscious of its source material. It asks new questions and finds satisfactory answers, while finding a new way to get at the subtextual themes of the original story — a story about children and about revenge.

You can argue that the Pied Piper story also implies a relationship between the human world and the natural world that’s gone out of true; and there’s some of that here. The village is set in a deep wood, and the images of the natural scenery are often breathtaking, a pleasant green world in which all seems right. And yet all is not right, and the rats are a sign of a curse upon the secluded village. That curse leads the villagers to enact the events of the story, ultimately cutting down the children who are the next generation: there is no fruitfulness in this village thanks to their actions and their curse.

This is a very dark film, and the theme of revenge is front and centre. As the nested lies and betrayals unfold on screen we know vaguely what’s coming because of the resemblance to the original story, but the twists in the retelling make it new and even more horrific. The increasing violence is always in the service of character, and serves to give the story an almost operatic feel thanks to the overtones of magic and myth. The characters seem to be playing out a dance or ritual, each acting their part as the story works itself through.

This is a very dark film, and the theme of revenge is front and centre. As the nested lies and betrayals unfold on screen we know vaguely what’s coming because of the resemblance to the original story, but the twists in the retelling make it new and even more horrific. The increasing violence is always in the service of character, and serves to give the story an almost operatic feel thanks to the overtones of magic and myth. The characters seem to be playing out a dance or ritual, each acting their part as the story works itself through.

Yet the feeling is less one of mystery than of consciously-crafted absurdity. Which is to say, if it’s mythic, it’s a kind of existentialist myth. Caught in an inexplicable world, the characters make choices that serve only to turn other characters against them and bring ruin on everyone. The piper ends made up like a clown, leading a procession to death, and if this is sinister it also seems to show how mad the need for revenge is: this is where the basest parts of your nature will lead you.

The film manages to maintain a real sense of tragedy, if also of theatricality. There’s an inevitability in this movie, an intimation of inexorable doom, that feels earned. The violence that erupts has an almost Shakespearean flavour, the centrality of revenge to the plot recalling (to me) Renaissance revenge tragedies. As I’ve said, there is a sense of ritual, of sacrifices and scapegoats. It’s cathartic, not uplifting.

What may be surprising is that to my inexpert ear the piper’s music did not seem to lend much of a shape to the film. The music is of course central to the plot but was almost unremarked on. The man has a gift, and there’s an end to it. In the world of the film, it makes sense; it’s a knack, such as anyone might have. While noting quibbles, I will say also that some key flashbacks don’t feel to me particularly well integrated into the story — the village’s background seemed to emerge at an odd moment, and fit oddly into the overall narrative. It works, but the scenes stick out in an odd way.

What may be surprising is that to my inexpert ear the piper’s music did not seem to lend much of a shape to the film. The music is of course central to the plot but was almost unremarked on. The man has a gift, and there’s an end to it. In the world of the film, it makes sense; it’s a knack, such as anyone might have. While noting quibbles, I will say also that some key flashbacks don’t feel to me particularly well integrated into the story — the village’s background seemed to emerge at an odd moment, and fit oddly into the overall narrative. It works, but the scenes stick out in an odd way.

Still, that’s only because the story otherwise proceeds so smoothly. Kim Kwang-tae has fit the Pied Piper tale into a specific time and place that work perfectly. It is almost certain that there are allusions to the postwar political situation that I didn’t catch — the village keeps itself isolated because it believes that the war’s still going on, for example, and if that doesn’t pay off much on a plot level it seems to carry some weight of meaning. But then it might only be that this is a movie about the guilt of the collective, as much as it’s about a failed attempt by a man to construct a new family and a new home for himself.

Kim’s brought out themes implicit in the legend and turned it into a humanistic fable. It’s a powerful example of how to retell a story and adapt it to a new setting. There’s a cool intelligence and a strong dramatic sensibility behind this movie, and the result is a story that’s both fascinating and involving. I would hesitate to call it a masterpiece, but it is a very strong work that finds powerful meaning in its source material.

It was a good day for me, if a little brief. Two movies, one actively good and the other at least interesting albeit disappointing. The festival was nearly over, but I still had one more day of films to go. After that it would be time to reflect on what I’d seen; and these movies would provide interesting food for thought.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.