Oz’s Bag of Holding: Stephen King Edition featuring A Brief Guide, Fear Itself (with an essay by Fritz Leiber!), and Danse Macabre

I have here a bag of holding. I am going to pull some things out of it now…

I have here a bag of holding. I am going to pull some things out of it now…

First up is:

A Brief Guide to Stephen King: Contemporary Master of Suspense and Horror by Paul Simpson (2014)

Funny how I came across this one. I was perusing the bookshelves in The Dollar Tree — all those overstocks and remaindered copies now relegated to the fate of being sold for a dollar.

Every once in a while I make a “find,” but on this occasion, it was looking like there was good reason none of these books had sold for their original double-digit cover prices. The thought actually went through my head, “Too bad you never come across a book by Stephen King in here.” A moment later, King’s name caught my eye! Turns out it was a book not by but about King. Still, it was too much of a sign to ignore, so I bought it.

A Brief Guide is as advertised: a brief, workmanlike bibliography of all King’s work through 2014, with synopses of each. Opens with a short bio. Not a must for shelves of diehard King fans, but I actually found I had plowed through the whole book in two sittings — so it succeeded in its professed purpose as a succinct overview of the author’s career. Every King book, film and TV adaptation, and comic book is covered (indeed, even tie-ins like video games are included). While the synopses are quite short, the author livens it up a bit by including tidbits here and there relating a work to events in King’s own life at the time or King’s opinion or the reaction of critics.

Frankly, much more information on each individual work can now be found on Wikipedia and numerous other websites — but for those who still prefer a bibliography where the information is all in one place between the covers of a book that you can curl up with on the couch, this serves as that.

Frankly, much more information on each individual work can now be found on Wikipedia and numerous other websites — but for those who still prefer a bibliography where the information is all in one place between the covers of a book that you can curl up with on the couch, this serves as that.

One take-away: when some of King’s 800+ page books are distilled into a two or three paragraph synopsis, they sound absurd. Sometimes you find yourself thinking, “He wrote a War and Peace-length novel around that?” At times — like with the Dark Tower books — the synopses become nearly incoherent: they probably wouldn’t be very intelligible unless you’d already read the novel.

Next out of the bag:

Fear Itself: The Horror Fiction of Stephen King edited by Tim Underwood and Chuck Miller (pb edition 1984)

Excited when I came across this on the shelf in an antique store. Contains essays by some of the top names of the genre in the 1980s reflecting on the (then relatively short) oeuvre of King. Fritz Leiber on his impression of books like The Stand and The Shining? Hell yeah. It also includes an introduction by Peter Straub, a foreword by King himself, and an afterword by George Romero (then working with King on Creepshow!). In between are perspectives by the likes of Charles L. Grant, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, and Douglas E. Winter.

One wishes we could read these same authors’ opinions now, looking back at King’s five decades of output. Of course, some of these luminaries have long since passed away. What’s interesting is that many of their initial assessments would still stand: King has been a remarkably consistent writer, good and bad.

His tendency to “over-write” (both in “quality and quantity,” as Leiber puts it) was, of course, already on full display and open to criticism.

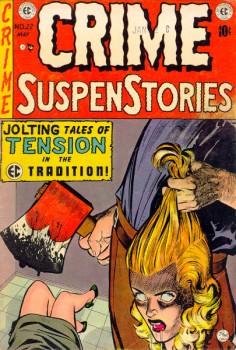

Ditto his tendency not to take his monsters very seriously, to rely more on restaging old horror tropes and EC Comics-style horrors than on seriously working out new imaginings of the boogeyman. For freshness and impact he has, instead, always relied on setting them into familiar, contemporary surroundings; the sweat of his creative imagination is spent on making the human characters feel real. As King himself explained of his method early in his career, a vampire is an absurd thing that no one really believes in; to make the vampire truly scary one must focus on the believability of the character being menaced by the vampire: we are scared because we identify with the character and the character is scared.

When the film adaptations up to that point are assessed, it’s already clear that his work was capable of generating both good films and, as Leiber characterizes them, “b-minus horror flicks.” The analytical set for this assessment was, at that time, only about a half-dozen films. Now there are literally dozens (58 film and TV adaptations as of July, according to iO9), and it has held true through what has become almost a film sub-genre unto itself.

His work has regrettably brought us clunkers like Maximum Overdrive and The Lawnmower Man as well as inspired classics like Stand by Me and The Green Mile. Even the same work can hit and miss in different incarnations, depending on the director and producers: Stanley Kubrick’s original take on The Shining is now regarded as one of the great horror films, even though King was gravely disappointed in it (Leiber, notably, shared King’s disapproval of Kubrick’s take). Brian de Palma’s Carrie is also considered a classic, while subsequent remakes of both films are largely dismissed by fans and critics alike.

Another thing some fans were saying back in ‘82 has borne out: Folks like John D. MacDonald were predicting King had some good literary works in him that would not rely on science fiction or the supernatural. King has indeed produced several such works, which have been lauded by more critics than anyone probably would have guessed back when Pet Semetary was hitting the newsstands (hell, in 2003 he received the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters!).

I’ll confess I haven’t read any of those more “serious” books: I go to King for popcorn horror, yes, for his brand: I want the King who uses monsters to go “booga-booga,” less interested in the King who solely relies on the horrors of real life. (I don’t go to the Northwoods Candy Emporium to shop for organic vegetables.)

To be fair, part of what makes his supernatural horror so effective is how he so aptly layers in real details and convincingly creates characters who feel like our friends, family, and next-door neighbors. (This, to me, has always been King’s greatest strength as a horror writer: his ability to create people who feel real and whom you intuitively like and care about. You are strongly rooting for them, and are crushed when, sometimes, the monster gets them.) Whether he is threatening his characters with vampires or Lovecraftian Old Ones or cell phone signals that turn people into zombie-like maniacs, he is able to draw upon the subtext of real horrors to imbue his monster puppets with real menace. And he makes them matter, not because the monsters are credible, but because the people are.

To be fair, part of what makes his supernatural horror so effective is how he so aptly layers in real details and convincingly creates characters who feel like our friends, family, and next-door neighbors. (This, to me, has always been King’s greatest strength as a horror writer: his ability to create people who feel real and whom you intuitively like and care about. You are strongly rooting for them, and are crushed when, sometimes, the monster gets them.) Whether he is threatening his characters with vampires or Lovecraftian Old Ones or cell phone signals that turn people into zombie-like maniacs, he is able to draw upon the subtext of real horrors to imbue his monster puppets with real menace. And he makes them matter, not because the monsters are credible, but because the people are.

That is no doubt a two-way street: when he turns to straight fiction, the palpable menace, the dread, the suspense are heightened by his mastery of horror tricks of the trade. There is a fine line between his “non-supernatural horror” and his “mainstream fiction.” I make this observation only on the basis of the non-horror short stories and novellas that I’ve read because they were snuck in among the giant rats and risen corpses that populate his short-story collections. Indeed, “Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption” is one of my favorite King stories. And its film adapation, The Shawshank Redemption, is rightfully regarded as one of the best American films of the late-twentieth century.

With his mantle of the “modern master of horror,” he is able to turn his “toolbox” (as he describes it in On Writing — which is now considered by many to be one of the best books ever written on its subject) to the task of imbuing the everyday world with nightmares from our darkest closets. When they emerge, you don’t need the Boogeyman to shamble out as an embodiment of them. (But I still prefer the Boogeyman. My nightmares are stoked quite enough by the nightly news, thank you.)

Final note: In Alan Ryan’s contribution to Fear Itself, “The Marsten House in ‘Salem’s Lot,” Ryan makes an observation that speaks directly to what I noted in my reading of A Brief Guide to Stephen King (namely that many of King’s books, when summarized, sound absurd): “Try stating in plain language the plot or premise of a favorite horror story. Chances are good that, stripped down that way, it sounds pretty silly. No, it’s all in the telling…”(193).

That, more than anything else, may offer the key to King’s success: what is sometimes cited by some critics as a weakness — the piling on of too much of the mundane — is, in fact, what gives him the ability to trot out hokey old monsters and tired horror tropes and revitalize them, re-invigorating them with the ability to evoke real fear. Choosing just the right details, readily recognizable to us from our own everyday lives, and crafting characters who are sympathetically familiar and real, King masterfully lulls us into suspending disbelief and going along for the ride.

And finally, a classic…

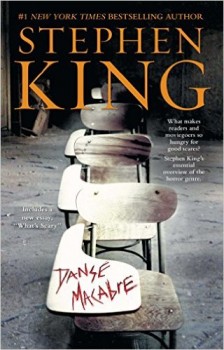

Danse Macabre by Stephen King (trade paperback edition 2010)

This happens to be the King book I have read more times than any other (it is surely in the Top 10 of books I have returned to most). This 1981 overview of horror in various mediums from 1950 to 1980 I still find compellingly readable. I once used it in a horror class I taught, and I guess I’ve read all or parts of it at least half-a-dozen times. I ask myself why? Some of his observations are clunky, some of his analyses off-base. Why do I like this book so much?

This happens to be the King book I have read more times than any other (it is surely in the Top 10 of books I have returned to most). This 1981 overview of horror in various mediums from 1950 to 1980 I still find compellingly readable. I once used it in a horror class I taught, and I guess I’ve read all or parts of it at least half-a-dozen times. I ask myself why? Some of his observations are clunky, some of his analyses off-base. Why do I like this book so much?

I think it’s because this is one of a precious few non-fiction books where I feel like I’m having a conversation with the author; it comes close to feeling like the sort of sustained conversation on a topic that I would have with my dearest friends — in this case, if we stayed up late into the night jawing about our favorite horror stories and films.

Unsurprisingly, I’ve long wished he would do an Updated version to cover all the great horror works that have come post-1980. In the 2010 re-release of the book, he did go partway to alleviating this by including a forenote (“What’s Scary?”) in which he briefly shares his thoughts on some of the most notable horror films of the prior decade. With some of his observations, I found myself nodding my head wholeheartedly in kindred appreciation; I strongly disagreed with others (I did not care at all for The Strangers, which he loved — but such disagreements will inevitably arise even in that late-night conversation with a chum).

I don’t think King has any intention of producing an Expanded edition or a Danse Macabre II, covering the period 1981-2010, so we will have to be content with this. And if someone else takes on the task, I hope he or she will be able to capture that casual, conversational attitude of a fellow fan — and not simply deliver another book that reads like an expansion of someone’s dry, academic Thesis paper.

Brief Guide by Paul Simpson, paperback published by Running Press, has a cover price of $13.95 but is currently being remaindered and can be found online for little more than the cost of postage.

Fear Itself is out of print in its original and 1993 reprint editions, but copies of it can be found online for little more than the cost of postage.

Danse Macabre, the 2010 trade paperback edition from Gallery Books, is in print with a cover price of $17. As with all of King’s books, multiple editions and formats can be found.

Great post! I agree with many of your insights here, though I’m probably not as much of a King fan as you.

I was struck by the following Alan Ryan quote about King: ““Try stating in plain language the plot or premise of a favorite horror story. Chances are good that, stripped down that way, it sounds pretty silly. No, it’s all in the telling…”(193).

I said exactly the same thing about horror writer Nathan Ballingrud in a Blackgate post back in May, 2014: “it will surprise many that Ballingrud makes use of some fairly old-school horror and fantasy tropes: werewolves, vampires, zombies, serial killers, monsters, . . ., etc. But such items are usually merely dressing for the real terrors — the horror of people’s mundane or tortured lives.”

Ballingrud and King are very different writers. But it’s interesting that they seem to be similar in this regards. I wonder how many other horror writer’s might fit this description?

“I wonder how many other horror writers might fit this description?”

I suspect there are many, given King’s influence on the whole genre since the ’80s.

Or think of a recent successful horror film like It Follows. The monster, if you stop to analyze It, is almost nonsensical (If It quickly kills off anyone who “contracts” Its sexually-transmitted haunting, how the hell did Hugh ever figure out all the intel he has on It?). What sucks the viewer in is the well-drawn, relatable characters, empathizing with them as they do their level best to face the irrational horror.