Fantasia 2016, Day 18, Part 1: Lunar Zombies (Train to Busan and Operation: Avalanche)

On the morning of Sunday, August 1, I was in no particular hurry to get to the Hall Theatre. I planned to see the Korean zombie movie Train to Busan, but knowing it had already played the large room of the Hall once I didn’t anticipate I’d have difficulty finding a seat. I intended after that to go across the street to the De Sève Theatre, where I’d watch Operation: Avalanche, a found-footage fiction about filmmakers who’d faked the moon landing in 1969. Then I’d go have a bite to eat and come back for two more movies. It sounded like a nice well-spaced day, but when I got to the Hall ten minutes before Train to Busan was scheduled to start I found I’d radically underestimated the film’s popularity. As the doors opened to let the ticket-holders in, the line stretched around the corner, up to the next street, and then around the corner there. Luckily enough, I was able to find a good seat in the back of the Hall, where I watched the auditorium fill up with an enthusiastic crowd.

On the morning of Sunday, August 1, I was in no particular hurry to get to the Hall Theatre. I planned to see the Korean zombie movie Train to Busan, but knowing it had already played the large room of the Hall once I didn’t anticipate I’d have difficulty finding a seat. I intended after that to go across the street to the De Sève Theatre, where I’d watch Operation: Avalanche, a found-footage fiction about filmmakers who’d faked the moon landing in 1969. Then I’d go have a bite to eat and come back for two more movies. It sounded like a nice well-spaced day, but when I got to the Hall ten minutes before Train to Busan was scheduled to start I found I’d radically underestimated the film’s popularity. As the doors opened to let the ticket-holders in, the line stretched around the corner, up to the next street, and then around the corner there. Luckily enough, I was able to find a good seat in the back of the Hall, where I watched the auditorium fill up with an enthusiastic crowd.

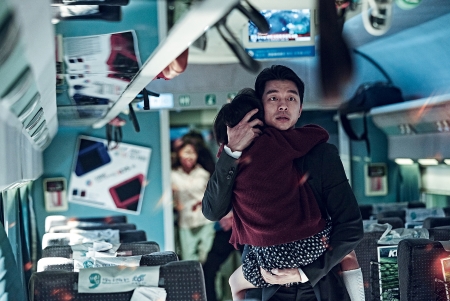

Train to Busan was directed and written by Yeon Sang-ho, whose animated zombie film Seoul Station I’d already seen at this year’s festival (some sources claim the two movies take place during the same zombie outbreak, but there’s no necessary connection between them — though it is interesting they both revolve around very different father-daughter relationships). The live-action film begins with a brief prologue mentioning a “leak at the biotech district.” Then we get to our main characters, Seok-woo (Yoo Gong), a callous divorced stockbroker taking his daughter Su-an (Kim Su-an) to Busan by train to spend her birthday with her mother. But something’s going on around them as the train starts on its way, and that something has made its way onto the train as well. This introductory section’s relatively slow, setting up characters and sub-plots on the train; and then the violence begins.

One zombie begets another. Characters begin to die. Slowly the survivors begin to understand what they’re dealing with, begin to work out the rules by which these creatures operate. Faced with horror, everyone does what they think they have to in order to ensure their own survival — and since this a Yeon Sang-ho movie, “pulling together for the common good” is off the table as an option. Some characters do learn to work as a team. Others use a knack for betrayal. Whatever it takes to live.

The tension builds nicely, and the action choreography is strong. The story moves through a series of set-pieces, establishing the distinctive rules by which the fast-motion zombies operate, establishing the train architecture and how it operates, and then giving the characters a series of problems in which they have to use the features of the train to get through the zombies. It does a good job of thinking up those problems, and of varying the events on the train. Passengers are whittled down at a fast clip, while survivors establish character by their reactions to the horror around them. This in turn sets up some effective tragic moments, scenes of heroic sacrifice, and at least one misanthropic action that got a loud cheer. Venality and cowardice emerge in many of the surviving humans under threat; it’s easy to read the film as pro-zombie.

The tension builds nicely, and the action choreography is strong. The story moves through a series of set-pieces, establishing the distinctive rules by which the fast-motion zombies operate, establishing the train architecture and how it operates, and then giving the characters a series of problems in which they have to use the features of the train to get through the zombies. It does a good job of thinking up those problems, and of varying the events on the train. Passengers are whittled down at a fast clip, while survivors establish character by their reactions to the horror around them. This in turn sets up some effective tragic moments, scenes of heroic sacrifice, and at least one misanthropic action that got a loud cheer. Venality and cowardice emerge in many of the surviving humans under threat; it’s easy to read the film as pro-zombie.

The zombies act as a group, a ravening horde with one goal to which they move directly and without question. The living, as in Seoul Station, may be individually heroic but also may be much worse than the dead. Again as in Seoul Station, the worst are full of passionate intensity, and it turns out that the living will listen to anyone, however bumptious or self-regarding, who seems to have a plan. Even if that plan calls for other people to be sacrificed.

Dramatically, there’s a tightness to the action on the train, to the betrayals and reversals. But once the train reaches its destination (or almost), and the action moves away from the contained environment, things become dicier. Bad stuff keeps happening, but feels much more contrived. Instead of characters stabbing each other in the back, the universe itself seems to have it in for them. There’s no inherent logic to why things work out one way instead of another; mischance here is just chance. The very last moments of the film, for example, wring drama out of a military unit that’s been set up in a remarkably odd position.

It’s a symptom of a larger problem: once off the train, the narrative momentum of the movie begins to flag. At just shy two hours (118 minutes, to be precise) it begins to feel overlong. The film’s at its best when it is, basically, Die Hard on a train with zombies. That’s not a bad concept to be getting on with, and the various set pieces and character bits work nicely within that high concept. Then in what is basically the third act of the film, that set-up’s broken. On the one hand the movie’s trying to challenge its own formula, which is fine. But on the other, the results feel contrived — and point up the contrivance of the rest of the film.

It’s a symptom of a larger problem: once off the train, the narrative momentum of the movie begins to flag. At just shy two hours (118 minutes, to be precise) it begins to feel overlong. The film’s at its best when it is, basically, Die Hard on a train with zombies. That’s not a bad concept to be getting on with, and the various set pieces and character bits work nicely within that high concept. Then in what is basically the third act of the film, that set-up’s broken. On the one hand the movie’s trying to challenge its own formula, which is fine. But on the other, the results feel contrived — and point up the contrivance of the rest of the film.

Having said all this, as a weakness it’s an outgrowth of the movie’s strength: it keeps finding new things to do. It doesn’t just run through set-pieces, it keeps changing the status quo of the survivors on the train. For a movie with a relatively simple premise, it manages to find a variety of tones across a variety of sections. This ought to feel episodic, if not shambolic, so the fact that never really happens until the last section of the film should perhaps be viewed as a success.

Visually, the film never lets up, in terms of pacing and creativity. Yeon’s made a sleek, skillful film, even when he’s showing scenes of total devastation. He brings a sense of scale to the destruction without losing the sense of the characters who we’re following through the film. The slow growth of Seok-woo makes a solid if not particularly subtle or surprising character arc, while the variety of death scenes along the way are well-chosen in the range of tones they create, tragic or comic or both at once.

I said that by the end the film feels like it goes on a bit too long; part of that, again, comes from what we see when the train reaches the end of the line. The idea of safety is thoroughly undercut, which makes the film feel oddly moot. Not quite everyone dies here, but one does feel it’s just a matter of time. Perhaps the point is that all we can hope for is to die well, but I don’t get that sense; the film’s too bleak, too cynical. Well or poorly, everyone dies. That’s a fine theme, but is a bit overdetermined when all’s said and done.

I said that by the end the film feels like it goes on a bit too long; part of that, again, comes from what we see when the train reaches the end of the line. The idea of safety is thoroughly undercut, which makes the film feel oddly moot. Not quite everyone dies here, but one does feel it’s just a matter of time. Perhaps the point is that all we can hope for is to die well, but I don’t get that sense; the film’s too bleak, too cynical. Well or poorly, everyone dies. That’s a fine theme, but is a bit overdetermined when all’s said and done.

Train to Busan is not the best Korean movie about a possible end of the world set on board a train that I’ve ever seen. I’m not sure it’s even the bleakest. It is, however, the most (well, ‘more’) linear and at least superficially more plausible. It’s a basically entertaining, well-shot action movie that feels a little like it loses its way at the end and perhaps goes on too long. Clever and inventive, it’s a fine addition to the quickly-growing infestation of zombie movies.

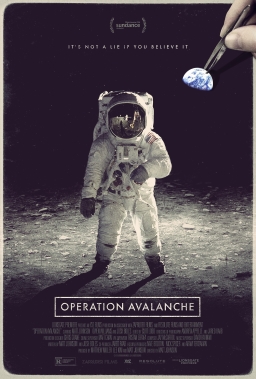

Operation: Avalanche was next. Directed by Matt Johnson from a script by Johnson and Josh Boles, it’s a period piece set in the late 1960s. Johnson plays a character named Matt Johnson, who along with his partner Owen Williams (played by, you guessed it, Owen Williams) are CIA agents who’ve just completed an investigation, Operation: Deep Red, proving that Stanley Kubrick is not a Communist pawn. Their new mission is to infiltrate NASA, looking for signs of a Soviet spy inside the space agency as it prepares to put a man on the moon. They end up uncovering something disturbing: NASA’s not going to have the landing gear ready for use at the time of the moon shot. There will be no moon landing, and America’s credibility (runs the thinking) will be tremendously damaged. Johnson makes a daring proposal to his superiors: let him fake a moon landing with cutting-edge (for 1967) special effects.

The plot sets up an unconventional mix of satire and thriller. The film’s told in the form of found footage, which is appropriate: in a movie about the falsification of reality by film, film reality is falsified. You’re never quite sure what it is you’re watching; the real-life Johnson and Williams in fact did some unauthorised filming at NASA to add to the film’s reality. Tonally, the movie’s at first unsettlingly bleak for a comedy and then darkly comic for a thriller. The story ramps up slowly, turning bit by bit into a dark and suspenseful film about cat-and-mouse spy games while never entirely losing its original comic sense.

The plot sets up an unconventional mix of satire and thriller. The film’s told in the form of found footage, which is appropriate: in a movie about the falsification of reality by film, film reality is falsified. You’re never quite sure what it is you’re watching; the real-life Johnson and Williams in fact did some unauthorised filming at NASA to add to the film’s reality. Tonally, the movie’s at first unsettlingly bleak for a comedy and then darkly comic for a thriller. The story ramps up slowly, turning bit by bit into a dark and suspenseful film about cat-and-mouse spy games while never entirely losing its original comic sense.

At the same time, the movie’s theme becomes clearer and clearer: art and forgery. Creation. Johnson (in the film) is a director planning one of the most ambitious film projects of all time. At first determined to use the project as a way to demonstrate how good he is at his job, he becomes increasingly fixated on the film as a film, working out new techniques to better fake the moon landing. In a sense, that’s what cinema is — making things look good for the camera. Trick the camera into believing something’s real, and it’ll look real. And fake moon shots have been a part of film since Georges Méliès.

The movie calls attention to itself being filmed, challenging the audience to look past artifice. We see Johnson fast-talking his way onto the set of Kubrick’s 2001 and see him talking to Kubrick — which is impossible, but the illusion’s perfect. That’s the point. The sense of period is impeccable, even as the found footage technique frays badly as the film goes along. That’s deliberate, I think, as Johnson (the real director) is careful to keep a certain level of plausibility: we see Johnson (the character) editing together much of the film we’re watching, and burying an early version of it in a field. The movie’s conscious of its form, but conscious of itself as a fiction. So it’s a story conscious of itself as a story, but also coherent as a story, and as a story about the process of storytelling.

For all that, the movie’s also a character piece. Storytelling and forgery and the power of film all come together in the character of the fictional Matt Johnson. He’s excitable and strong-willed and foolish with the foolishness of a man who doesn’t know when not to do something — a man who doesn’t know when something’s impossible. Ideal characteristics for a movie director, all around. Increasingly caught up in his own project, he lies to his friends and allies in the service of his art: he does what he has to do to complete his work. In so doing, he moves deeper into the shadowy world of espionage, into the moral greyness of the spy. The deception of the undercover operator becomes indistinguishable from the work of the actor. Again we’re challenged to puzzle out truth and fiction.

The performances of Operation: Avalanche itself are very strong. As a period piece Johnson’s affect is a little odd, as though not quite in tune with his character’s era. The dialogue’s fine, without too many anachronisms that I noticed. Generally the movie’s very effective at using period incidents — a resignation, a death — to advance its story. Of course the figurative and literal countdown to the moon landing provides a ticking clock to keep the tension on; for all the documentary-style seeming realism, this is a very well-constructed film.

The performances of Operation: Avalanche itself are very strong. As a period piece Johnson’s affect is a little odd, as though not quite in tune with his character’s era. The dialogue’s fine, without too many anachronisms that I noticed. Generally the movie’s very effective at using period incidents — a resignation, a death — to advance its story. Of course the figurative and literal countdown to the moon landing provides a ticking clock to keep the tension on; for all the documentary-style seeming realism, this is a very well-constructed film.

It is, of course, an exercise in taking post-Watergate cynicism about government and governmental lies, and projecting that cynicism like a filmed image back onto earlier years. But then, the real Matt Johnson is Canadian, so it’s also in the venerable tradition of Canadians taking the piss out of American triumphalism. Either way there’s at least a skepticism about the idea of American prestige, and how valuable it really is. Did the moon shot really mean that much in pragmatic Cold War terms? Would it have been worth human lives? How much was American policy in the Cold War a jumping at shadows, an overreaction to a real threat?

There’s next to no mention of the war in Vietnam, a very real example of costly paranoia. Instead the movie plays about with conspiracy theories of the moon landing, knowingly using fictions (albeit fictions believed by some) precisely as fictions in order to tell a story about stories. Of course Kubrick himself is brought into the film, just as the mythology of the moon conspiracy has it. Who better to use as a character in a film about filmmaking?

One cannot overlook the formal dexterity of Operation: Avalanche. Not just in its recreation of the late 60s, but also in its cinematography and guerrilla filmmaking. There’s an extended long-take car chase near the end that feels visceral and gripping, and must also have been as dangerous to shoot in real life as it was to the characters on screen. The technical skill and real daring help sell the themes of the film, the questions about the truth of images and what you can believe of what you see. At the end there’s a touching moment as the fictional Johnson sees the result of all his work: it’s a moment that brings home his accomplishment as an artist, and emphasises the nature of film as art — as well as the link of art and artifice. He’s done great work in a dubious cause. It makes a strong emotional beat, and rounds off the work of art that is Operation: Avalanche. The point of the film, perhaps, is that you can’t count on film for literal truth. You can only count on art for human truth. Which is perhaps more important.

After the film, Matt Johnson, Owen Williams, and many of the other cast and crew of the film came out to take questions. The first was about the way Kubrick was integrated into the film, and Johnson said that there was in fact no high-definition footage of Kubrick — they’d had to take photos of Kubrick and recreate them three-dimensionally in a computer, a process that took six months. Asked how they’d settled on the moon-landing conspiracies as a subject, Johnson said that the conspiracy made for a great story, in some ways something even more exciting than the reality of putting a man on the moon. They took what seemed most germane from the various conspiracies, obviously including the involvement of Stanley Kubrick.

After the film, Matt Johnson, Owen Williams, and many of the other cast and crew of the film came out to take questions. The first was about the way Kubrick was integrated into the film, and Johnson said that there was in fact no high-definition footage of Kubrick — they’d had to take photos of Kubrick and recreate them three-dimensionally in a computer, a process that took six months. Asked how they’d settled on the moon-landing conspiracies as a subject, Johnson said that the conspiracy made for a great story, in some ways something even more exciting than the reality of putting a man on the moon. They took what seemed most germane from the various conspiracies, obviously including the involvement of Stanley Kubrick.

Asked about the research for the film, Johnson said NASA agreed to give them footage, and some came from the largest single private holder of Apollo footage. At the same time Johnson pointed out a character who was an actual NASA employee who was led to believe that they were shooting a legitimate documentary. A brief discussion followed regarding an anecdote about Buzz Aldrin punching a conspiracy theorist (Johnson believed Aldrin got a bad rap, pointing to bad behaviour on the part of the man who got punched). Asked whether any of the filmmakers believed in the conspiracies, they all denied it, and said that Operation: Avalanche would be a very different movie if it had been made by people who believed in a conspiracy. Instead, Johnson said the goal was to provoke a kind of cognitive dissonance in the audience, putting them in a space where they don’t know what’s true or what the filmmakers believe or what reality is.

A question came about the car chase scene toward the end of the film, and cameraman Andy Appelle said it took 7 or 8 takes to do all the way through, with each take getting crazier and more dangerous. He had to take off his seat belt to handle the camera; there was no tow car; no insurance company was involved; they started at 9 in the morning and finished it after sunset, in the so-called magic hour when there’s still light in the sky. Co-producer and cameraman Jared Raab noted that one of the windows blew out, leaving him rolling around in shattered glass. Asked how the filmmakers had matched the look of 16mm film, Raab said they’d tried to do it digitally, with frame-by-frame transfer from digital cameras. Some of it instead had been shot on film, as it would have cost a million dollars otherwise. Finally, asked how long he’d been interested in the moon landing, Johnson said that after completing his previous film The Dirties he’d wanted to do a film set in the 1800s, a found-footage movie set on a pirate ship; he’d moved the timeline up until he’d settled on the moon landing. He’d been surprised to find that nobody had done a found-footage movie about a conspiracy around the moon landing. He thought it was natural to tie the idea in with the idea of the falseness of the image.

That ended the questions, with a mention that the film would have a theatrical run starting in late September and would be available digitally in January (and also with an anecdote from Johnson about meeting Kit Harrington, who plays Jon Snow on A Game of Thrones — according to Johnson, Harrington’s maybe 5 foot 3). It had been a good afternoon, I thought. A slick action movie with a bit of thought behind it, and a thoughtful satire with a bit of action in it. Good genre stories, both of them, both of them using and challenging conventions. Operation: Avalanche did so more thoroughly, but Train to Busan had perhaps a bleaker worldview. Either way, a good afternoon, setting up what would be a decidedly mixed evening.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I just watched trailers for _Train to Busan_, which make it look like a sequence of variations on the WWZ plane scene. It looks incredibly intense, to the point of being exhausting.

Haven’t seen WWZ — I read the book and enjoyed it, but I gather they’re very different things. I would say Train to Busan does a good job of varying pacing, but you’re right that it is generally very intense. The kind of intensity varies, though; sometimes it’s tension, sometimes it’s desperate action, that sort of thing. I didn’t find it exhausting, but, as is always the case, your mileage may vary.