John Crowley’s Aegypt Cycle, Books One and Two

Elsewhere in the hallowed halls of Black Gate, you can find my musings on what I consider to be among the best and most endearing fantasy novels ever written, Little, Big. Perhaps its author, John Crowley, could have hung up his spurs after that one, certain that his honorifics were now firmly in place, his spot in the pantheon assured. But then, Little, Big was never a major financial success, never “popular,” and besides, Crowley is that rare jewel, a writer who is also a thinker, and he wasn’t done thinking.

Elsewhere in the hallowed halls of Black Gate, you can find my musings on what I consider to be among the best and most endearing fantasy novels ever written, Little, Big. Perhaps its author, John Crowley, could have hung up his spurs after that one, certain that his honorifics were now firmly in place, his spot in the pantheon assured. But then, Little, Big was never a major financial success, never “popular,” and besides, Crowley is that rare jewel, a writer who is also a thinker, and he wasn’t done thinking.

Among the works that have followed is The Aegypt Cycle, beginning with The Solitudes and Love and Sleep, then extending into Demonomania and Endless Things. I read The Solitudes in early 2015, and, having finished, set it down with a pensive hmmm, the same restless yet satisfied noise made by those who encounter an attractive puzzle box more devious and brilliant than themselves.

At the risk of sounding like a bent brown puppet from The Dark Crystal, let me repeat that: Hmmm.

Little, Big is sufficiently mysterious for most mortals, the equivalent of a buffet so satisfying and sumptuous that one reaches the end and returns at once to the beginning, eager to begin again. (Which I, in fact, did; I read the damn thing twice in a row.)

But the story of Little, Big contains at least the seeds of a deadline, an ill-defined apocalypse or renewal that, when it arrives, will change the world forever. This sets in motion a narrative engine that keeps even Crowley’s most self-indulgent dalliances chugging along, right to the end.

But the story of Little, Big contains at least the seeds of a deadline, an ill-defined apocalypse or renewal that, when it arrives, will change the world forever. This sets in motion a narrative engine that keeps even Crowley’s most self-indulgent dalliances chugging along, right to the end.

The Solitudes and Love and Sleep offer no such promise. Indeed, I am at something of a loss to explain what the books are about.

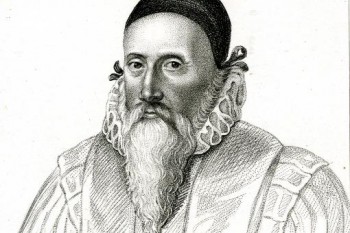

That they center on Pierce Moffat, a historian fleeing his teaching life in New York City and landing, to his own surprise, in a pastoral upstate locale called the Faraway Hills, is verifiably true, but also insufficient. The story line keeps opening outwards (and again, and again, outwards and outwards again), first via a myriad of Faraway inhabitants (shepherds and scholars, Tarot dealers and children) and then into the Elizabethan renaissance, where we meet Doctor John Dee, astrologer and mystic and sometime advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. Dee is in possession of a crystalline stone that allows him, with the help of a moody medium named Kelley, to contact “angels,” and one in particular (Madimi) urges him to flee England, decamp to Poland, and beware of the great Italian scholar with whom Dee’s fate is linked, Giordano Bruno.

But now I find myself consternated, forced into the unhappy position of Carroll’s White Knight (who of course was really Carroll himself), intent on singing little Alice a song but unable to fix on what to call the song, for the name of the song is one thing, while what it actually is (or what it might be called by others) remains another kettle of fish.

But now I find myself consternated, forced into the unhappy position of Carroll’s White Knight (who of course was really Carroll himself), intent on singing little Alice a song but unable to fix on what to call the song, for the name of the song is one thing, while what it actually is (or what it might be called by others) remains another kettle of fish.

I will swear in any court of law that the above summary is correct. But. It’s also inept, lame as a three-legged lambikin, and likely beside the point.

As with Little, Big, the grit that lies at the center of the narrative pearl appears to be a Great Turning Point, as in a universal turning points: those magical, interstitial moments where one age rolls into the next.

With epochal concerns as his anchor chain, Crowley roams far and ranges wide. He’s never in a hurry. He resists plot and abjures acceleration. It’s not that dramatic events are absent, no, but they come interspersed with musings on faith, time, physics, sex, love, death: all those topics fit to drive humankind mad (assuming we are not already so). That he does this with prose beyond reproach is what keeps the pages turning. Crowley adores English, and all its myriad possibilities; one proceeds through the books for the same reason one keeps reading Keats, or Dickinson: for the beauty of the experience.

Of course other authors, too, have set out to explore the rise and fall of ages. In fantasy cycles, Robert Jordan springs to mind, with the martial cadence of his Wheel Of Time. Unlike Jordan, Crowley isn’t interested in heroes, or the fates of nations, armies, rulers. His great question (which poor Pierce Moffat is trying to solve, and turn into a book himself) is this: what if magic really did exist, in the past, because the world, in past ages, obeyed different rules? Rules we can no longer see or understand? That magic doesn’t function now is clear enough, but does that mean it never did? And if magic did once behave as wizards and writers and alchemists sometimes describe, then isn’t it possible that were the world to turn again –– were a new epoch to arrive –– magic might once again become ascendant?

Of course other authors, too, have set out to explore the rise and fall of ages. In fantasy cycles, Robert Jordan springs to mind, with the martial cadence of his Wheel Of Time. Unlike Jordan, Crowley isn’t interested in heroes, or the fates of nations, armies, rulers. His great question (which poor Pierce Moffat is trying to solve, and turn into a book himself) is this: what if magic really did exist, in the past, because the world, in past ages, obeyed different rules? Rules we can no longer see or understand? That magic doesn’t function now is clear enough, but does that mean it never did? And if magic did once behave as wizards and writers and alchemists sometimes describe, then isn’t it possible that were the world to turn again –– were a new epoch to arrive –– magic might once again become ascendant?

Heady stuff. And so far as I can tell, for all of Crowley’s acumen, he has not, as of the close of Love and Sleep, resolved these questions for himself. Most fiction writers hide or couch their explorations behind a veil of organized story, a crafted and crafty contrivance that prevents us from seeing that what answers they’ve found were, not so long ago, pending, unformed. The Aegypt Cycle leaves me feeling that Crowley has put all his Great Questions on the table at once, and he’s answering, chapter by chapter and word by word, as best he can.

This, then, is a journey of discovery, but it’s the ultimate high-wire act: I have no particular reason to believe that Crowley will be able to land the plane.

And yet I keep reading. Why shouldn’t I? I, too, have questions.

Let it also be said that it’s possible I’ve entirely missed or misapprehended Crowley’s driving concerns. I don’t claim to be the brightest can in the six-pack, though in general, when confronted by a book (words on a page, set in a generally predictable order) I feel up to the task of both immersion and interpretation. With The Aegypt Cycle? My confidence evaporates. I begin to suspect I wasn’t qualified to be included in the six-pack in the first place.

Let it also be said that it’s possible I’ve entirely missed or misapprehended Crowley’s driving concerns. I don’t claim to be the brightest can in the six-pack, though in general, when confronted by a book (words on a page, set in a generally predictable order) I feel up to the task of both immersion and interpretation. With The Aegypt Cycle? My confidence evaporates. I begin to suspect I wasn’t qualified to be included in the six-pack in the first place.

Fans of Little, Big will appreciate the occasional sly nod to that book’s existence, to its perhaps contemporaneous cast of characters. One example: in both books, a popular television program is the fictitious soap opera, A World Elsewhere. Also in both, questions of relational size rise to the fore: are small things in fact small, or are they like the universe (and divinity), infinitely large?

Historians will revel in Crowley’s Elizabethan sections, and those who know upstate New York or Kentuckian Appalachia, where Pierce Moffat and his cousins spend their childhood, will delight in one spot-on evocation after another. Crowley’s powers of observation are never, ever in doubt.

Unlike mine.

And so I leave you, two books from finishing the cycle.

Check back in 2018. One thousand pages, give or take, to go.

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published In the Wake Of Sister Blue along with three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.”

Away from Black Gate, he is the author of the supernatural quartet, The Skates, Sleeping Bear, Check-Out Time, and Bonesy, all published by Samhain and featuring his semi-dynamic duo of Renner & Quist. His short fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in Lightspeed, Unlikely Story, Betwixt, Black Static, The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review, Realms of Fantasy, Witness, The Beloit Fiction Journal, Talebones, Not One Of Us, Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet and many more. His author’s page at Goodreads can be found here, and his website is markrigney.net.