The Dandelion Dynasty and Sagrada Família

|

|

The Dandelion Dynasty is an attempt at melding two separate literary traditions, both of which I’ve been fortunate enough to inhabit.

One of them traces a lineage from ancient, fragmentary pre-dynastic legends and Warring States Period annals to the spare, vivid biographies in Records of the Grand Historian, to elegant Tang Dynasty lyric poems and politically subversive Yuan Dynasty plays and pre-modern Ming Dynasty novels, and thence to the first vernacular Chinese stories, whose awkward but also lively language is cobbled together by great writers who were also courageous translators and who enriched the new medium with neologisms and adopted grammatical structures and strange metaphors imported from the West, and finally, to the wuxia classics that revived the strength of Chinese storytelling and the modern web serials that represent the lives of men and women in a society seized by some of the greatest upheavals and tumultuous changes ever encountered by any human society, incorporating along the way historical romances, oral storytelling, and magnificent fantasies that have been built up by generations of artists, brick by brick, like the Great Wall itself.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

The other is rooted in the grand Classical Greco-Roman epics and Christian gospels, and also in the earthy vernacular music of the sombre and magnificent Beowulf as well as the chiaroscuro of political intrigue in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. From these origins it builds up to ever more skillful and sophisticated compositions by some of the greatest poets who ever sang in the English language, culminating in the magnum opus that is Milton’s Paradise Lost, whose modern English is inflected by a classical beauty imbued by a writer who switched from Latin to English as his preferred medium. From there, the canon blossomed through centuries of colonial conquest and globalization as more and more voices joined in to claim the language of conquest for their own use, recrafting it from an instrument of the imperial will to power to an instrument for empowerment, until there was no more single English canon, but a multitude of Englishes and English literary traditions.

Why combine them? Why blend them?

It will be noted that translation has played and continues to play an important role in both traditions. Translation and cultural negotiation and the construction of new languages and new literary forms from pieces of different traditions are the engines driving new vernacular literatures and the source of stories that can represent new experiences and changing societies.

The Dara of my Dandelion Dynasty series is just such a society in transition, a world poised on the border between the classical and the modern, between the scintillating prestige of the dead written word and the nascent, bubbly instability of the vernacular argument. It is only natural, then, to try to tell the story of such a world using a mosaic of techniques from at least two different literary traditions.

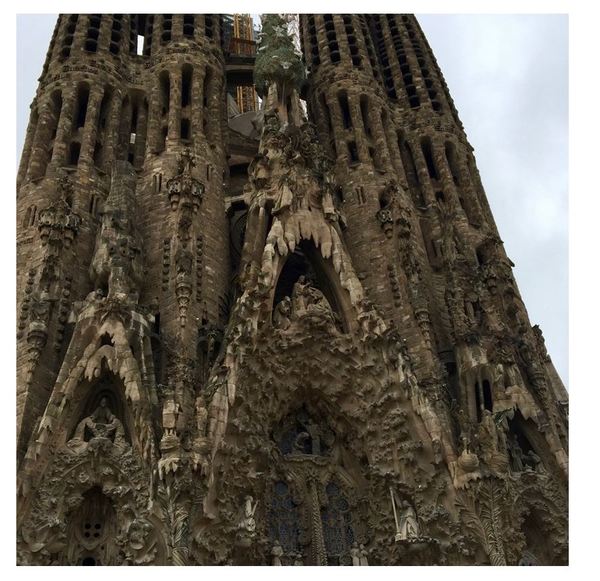

What other works of art follows such a design? The most striking example is probably the dream/nightmare-like Sagrada Família in Barcelona.

Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família, Barcelona, Nativity Façade

The two completed façades of the edifice, one facing east and one facing west, work together to construct a beauty formed from contrasts and harmonies and distant echoes and proximate oppositions that cannot be encompassed by one style of architecture or sculpture alone. Some truths are too grand to be represented by words in only one language or figures found in one pantheon.

Antoni Gaudí’s design for the church — which he never completed and which is still being added to by new artists and artisans, more than a century since the beginning of construction — was controversial and polarizing from the start. I think it the building closest in spirit to my series and love it with all my heart, but some, like George Orwell, called it “one of the most hideous buildings in the world.”

Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família, Barcelona, Passion Façade

I hope my novels can provoke just as strong a reaction.

Ken Liu is an author and translator of speculative fiction, as well as a lawyer and programmer. A winner of the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy awards, he has been published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s, Analog, Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and Strange Horizons, among other places.

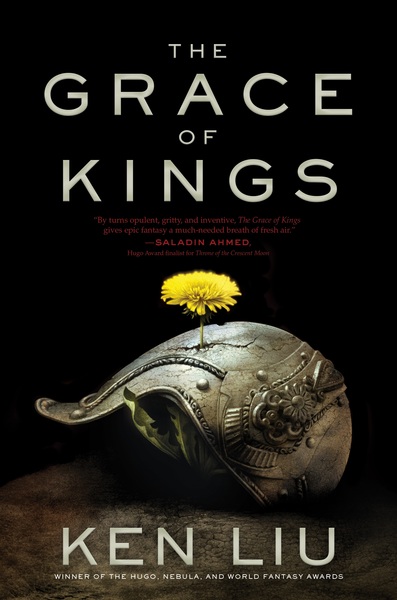

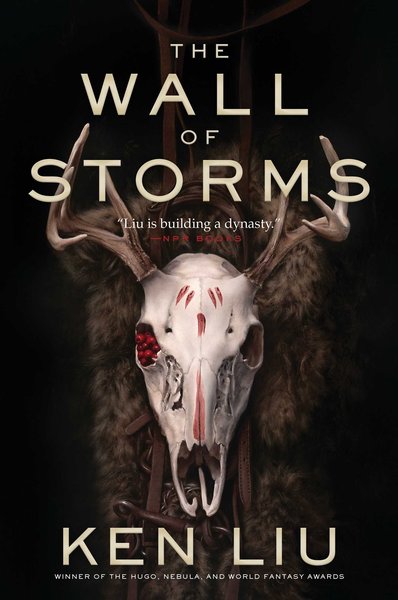

Ken’s debut novel was The Grace of Kings (2015). Its sequel, The Wall of Storms, went on sale this month. He also released a collection of short fiction, The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories (2016). He lives with his family near Boston, Massachusetts.

In addition to his original fiction, Ken is also the translator of numerous literary and genre works from Chinese to English. His translation of The Three Body Problem, by Liu Cixin, won the Hugo Award for Best Novel in 2015, the first translated novel to be so honored.

I saw your new book while I was browsing Amazon just yesterday!

I thought it was interesting how the cover of ‘Grace of Kings’ suggests ancient Chinese/Asian civilisation while the ‘Wall of Storms’ cover evokes something very different. (Neolithic hunter-gatherers? Siberian tribes?)

I’ll have to read them in the very near future. Hope the launch goes well!

Ken, I enjoyed The Grace of Kings and all the shorter fiction of yours that I’ve read. But was putting off purchasing The Wall of Storms because I have so many books to be read including The Paper Menagerie that I wanted to lessen that before adding more books. But your post was the nudge I needed to buy The Wall of Thrones.

You are one of the best young writers going. Keep up the great work.