Horror and Swords & Sorcery

The air has turned crisp, the sun is dipping below the horizon earlier each evening, and the supermarket candy section seems to have grown exponentially. Halloween is just around the corner and, like many of you, my mind has turned to haunts and frights.

Horror is one of the primary elements dividing swords & sorcery from epic fantasy. To quote the Horror Writers Association’s site, horror fiction is that which “elicits an emotional reaction that includes some aspect of fear or dread.” Horror has been intrinsic to the genre from its earliest days. Robert E. Howard’s heroes, Kull, Conan, Bran, and Solomon Kane all face off against supernatural horror. In general, the worlds of S&S are dark and dangerous. The protagonists, mostly loners, find themselves pitted against an inimical universe populated with carnivorous forces of darkness that sate their hunger on humanity.

Epic fantasy is concerned with things like the fate of the world, the battle between Light and Darkness, or big dynastic squabbles. There may be moments of terror in epic fantasy (e.g. LotR’s Watcher in the Water; A Song of Ice and Fire’s wights), but it’s rarely the main event. Not in every story, but in most of their S&S work, writers like Clark Ashton Smith, Karl Edward Wagner, and C. L. Moore, created tales that were horror first and foremost. They spun nightmares and darkness into thread and, along with strands of adventure and mystery, wove from it something moodier than Prof. Tolkien or his successors.

Clark Ashton Smith wrote some of the most dread-soaked stories in S&S. With lapidary prose, Smith composed stories that are almost suffocating in their intensity. In “Empire of the Necromancers,” two foul wizards revive a whole nation of the dead to serve them at their pleasure. In “The Testament of Athammaus,” a demonic bandit wreaks increasing degrees of terror on the city of Commoriom when his sentence of beheading fails to prove fatal. My favorite, the one that unsettles me the most, is “The Charnel God.” In a city where all the dead are claimed by the priests of the titular Mordiggian, young Phariom’s wife is taken when she slips into a cataleptic state. He follows Mordiggian’s priests to his temple, on a mission to rescue her:

The priests went on, and Phariom kept them in sight as well as he could in the blind tangle of streets. The way steepened, without affording any clear prospect of the levels below, and the houses seemed to crowd more closely, as if huddling back from a precipice. Finally the youth emerged behind his macabre guides in a sort of circular hollow at the city’s heart, where the temple of Mordiggian loomed alone and separate amid pavements of sad onyx, and funerary cedars whose green had blackened as if with the undeparting charnel shadows bequeathed by dead ages.

The edifice was built of a strange stone, hued as with the blackish purple of carnal decay: a stone that refused the ardent luster of noon, and the prodigality of dawn or sunset glory. It was low and windowless, having the form of a monstrous mausoleum. Its portals yawned sepulchrally in the gloom of the cedars.

Phariom watched the priests as they vanished within the portals, carrying the girl Arctela like phantoms who bear a phantom burden. The broad area of pavement between the recoiling houses and the temple was now deserted, but he did not venture to cross it in the blare of betraying daylight. Circling the area, he saw that there were several other entrances to the great fane, all open and unguarded. There was no sign of activity about the place; but he shuddered at the thought of that which was hidden within its walls, even as the feasting of worms is hidden in the marble tomb.

Like a vomiting of charnels, the abominations of which he had heard rose up before him in the sunlight; and again he drew close to madness, knowing that Elaith must lie among the dead, in the temple, with the foul umbrage of such things upon her, and that he, consumed with unremitting frenzy, must wait for the favorable shrouding of darkness before he could execute his nebulous, doubtful plan of rescue. In the meanwhile, she might awake, and perish from the mortal horror of her surroundings… or worse even than this might befall, if the whispered tales were true…

I have written of both Night Winds and Death Angel’s Shadow, Karl Edward Wagner’s short story collections about Kane, the murderous, always-plotting, swordsman and sorcerer (follow the links to the reviews). Neither title would look out of place gracing a mid-seventies horror novel, complete with embossed cover and garish artwork. The stories feature vengeful demons, a vampiric femme fatale, ghouls, a werewolf, and a half-dozen other things that regularly feature in a Mario Bava movie. While Smith’s stories are more about atmosphere and setting, Wagner’s are tightly wound scare-fests. As such, they are more plot-reliant, so I won’t give any of them away. Suffice it to say, I recommend them completely, particularly for this season.

Filled with trips to Hell and back, C. L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry stories are akin to one’s darkest dreams. They walk a line between Smith’s and Wagner’s stories, with ambience and narrative holding equal importance. Again, I won’t reveal anything about them except a few lines from my favorite Jirel story, “Hellsgarde.”

Hellsgarde — Hellsgarde and Andred. She did not want to remember the hideous old story, but she could not keep her mind off it this evening. Andred had been a big, violent man, passionate and willful and very cruel. Men hated him, but when the tale of his dying spread abroad even his enemies pitied Andred of Hellsgarde.

For the rumor of his treasure had drawn at last besiegers whom he could not overcome. Hellsgarde gate had fallen and the robber nobles who captured the castle searched in vain for the precious casket which Andred guarded. Torture could not loosen his lips, though they tried very terribly to make him speak. He was a powerful man, stubborn and brave. He lived a long while under torment, but he would not betray the hiding-place of his treasure.

They tore him limb from limb at last and cast his dismembered body into the quicksands, and came away empty-handed. No one ever found Andred’s treasure.

Since then for two hundred years Hellsgarde had lain empty. It was a dismal place, full of mists and fevers from the marsh, and Andred did not lie easy in the quicksands where his murderers had cast him. Dismembered and scattered broadcast over the marshes, yet he would not lie quiet. He had treasured his mysterious wealth with a love stronger than death itself, and legend said he walked Hellsgarde as jealously in death as in life.

Last week I put out a call on several swords & sorcery groups on Facebook asking for recommendations of swords & sorcery horror — other than Karl Edward Wagner. Here’re some of the answers I got:

Edward Wagner. Here’re some of the answers I got:

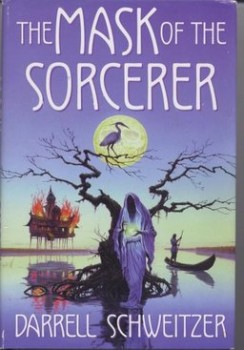

From John Fultz, Mask of the Sorcerer by Darrell Schweitzer, which he called “Harry Potter in Hell.” Schweitzer’s novel, The White Isle (reviewed here), and the collection We Are All Legends were strongly recommended too.

Stan Wagenaar suggested Chris Carlsen’s Berserker Trilogy. Carlsen was a pen name of the talented Robert Holdstock. The book isn’t available in the US yet, but I’m hoping it shows up soon.

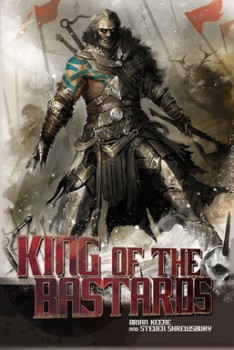

Charles Rutledge recommended Brian Keene and Steven Shrewsbury’s King of the Bastards.

Morgan Holmes offered up Ramsey Campbell’s Ryre stories and Joseph Payne Brennan’s Kerza stories. I have actually reviewed the former, but know nothing of the latter, though with the recommendation coming from Morgan, I feel an automatic need to hunt them down.

Morgan also suggested I look into the S&S stories, some written by Archie Goodwin and Gardner Fox, in the horror comics, Creepy, Eerie, and Vampirella.

Finally, several people suggested Brian Lumley’s Tarra Khash stories. I’ve reviewed several of these and have to concur, they are a fun mix of sword-swinging action and the creepy.

Just putting this together, I remembered that at least one of Charles Saunders’ Imaro stories found its way into a Karl Edward Wagner-edited Year’s Best Horror Stories. Andre Norton’s “The Toads of Grimmerdale” (which has been discussed a few times here at Black Gate), leaves me a little queasy each time I read it.

Just putting this together, I remembered that at least one of Charles Saunders’ Imaro stories found its way into a Karl Edward Wagner-edited Year’s Best Horror Stories. Andre Norton’s “The Toads of Grimmerdale” (which has been discussed a few times here at Black Gate), leaves me a little queasy each time I read it.

This dread, the fear of what’s lurking in the dark, waiting to strike, has been integral to S&S from they very beginning when Robert E. Howard took tried and true historical adventure fiction and mixed it with the burgeoning weird fiction of Lovecraft, Merritt, and others. Without it, fantasy is something else. Not bad, but not S&S.

Let me draw things to a close with a quote from Keith West regarding this subject, and which I stand by one hundred percent:

I think horror is essential to what makes sword and sorcery distinctive from other forms of fantasy adventure. The best S&S stories Robert E. Howard wrote are infused with a sense of dread or horror. Think “Tower of the Elephant” or “Worms of the Earth,” to name just two examples. Without the horror element, a lot of what is marketed as S&S is really just fantasy adventure with S&S trappings.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him. He’s also got four horror-related posts for your edification and amusement over there too — 1, 2, 3, and 4

Great post Fletcher! Thanks for sharing this! I love horrific S&S.

I’m not meaning to poke holes in your designation or get into genre definition squabbles. And I do think it’s true that horror is often an element in sword & sorcery, especially in contrast to what is just called fantasy.

However, I think of Michael Moorcock’s Elric stories and Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser stories are sword & sorcery as well. I can think of a handful of stories from both of these series that have horrific elements. But, overall, especially in contrast with Wagner and others you’ve listed here, I don’t see the horrific element as dominant.

For what it’s worth.

@James – Part of the point here was to encourage debate designations and genre definitions 🙂 Leiber and Moorcock are, of course, S&S. While not the dominant element, horror still figures strongly in their work. Think the god Hate or the Gods of Lankhmar in Leiber, or the various body horrors littering the Elric story (think the fate of Elric’s wife)

Interesting post, Fletcher. Although I wouldn’t necessarily agree, you did get me thinking. I’m pretty sure I’d recognise an S&S story if I read one, but defining what exactly constitutes S&S is a bit harder, as most of the key examples break one of the rules that typify the genre.

What if we extended the notion of “horror” to something like “grisliness”? One thing that S&S seems to typify, especially Moorcock, is giving the ghastly details of warfare.

If S&S is better characterized by grisliness, I wonder if Joe Abercrombie’s dark stuff qualifies as S&S? I don’t know. I’m only familiar with his YA stuff, which is definitely not S&S or grisly.

I suppose how central the horror element is to your definition of the S&S fuzzy set might depend on what you like. Me, I gravitate strongly toward S&S that contains cosmic horror, or at least cosmic weirdness, and tend to leave the rest by the wayside as mere gritty adventure fantasy. My favorite Elric story is probably the one from Sailor on the Seas of Fate where he and the other Champions realize that the giant semimechanical tower they’re exploring is actually the body of an extradimensional sorceress, and then merge into a horrifying multi-armed superwarrior to defeat her.

I guess there’s just something I like about pitting primitive hand weapons against malign cosmic superintelligences. For me, S&S is about elemental urges, the most primal of which is the fear of the infinite unknown that, for primeval man, stalked him in every dark forest. So my favorite S&S stories tend to be about a lone warrior pitted against the terror of the cosmos itself.

But, as Conan laconically remarks: “A devil from the Outer Dark. Oh, they’re nothing uncommon. They lurk as thick as fleas outside the belt of light which surrounds this world… Some find their way to earth, but when they do, they have to take on earthly form and flesh of some sort. A man like myself, with a sword, is a match for any amount of fangs and talons, infernal or terrestrial.”

Nice work Fletcher! I see what you are going with here, and no, S&S does not have to have a strong element of horror in it to be S&S. But it is better for it if it does. Worms of the Earth is possibly the best example of true, old-school S&S. And horror is at its core. My favorite Howard tale, People of the Dark, fairly wallows in it. And it is prominent in all the examples you have mentioned. Abercrombie, Cook, even Martin? More like epic fantasy or military fantasy to me. With elements of S&S, for sure. But not true S&S. Too damn long, for starters! Go back to what Keith West posted, read it. And read it again. Nuff said!

I noticed you (Fletcher) reviewed my favorite book – The Throne of Bones by Brian McNaughton – here also.

I think anyone who loves horrific sword and sorcery would like The Throne of Bones. While it is not really sword and sorcery. It is fantasy that is dark and horrific. Easy to imagine a grim and brooding warrior treading such a world.

I agree that horror is often an element of sword and sorcery. I agree with James McGlothlin, and was about to make the same point when I saw his post. I would consider the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories possibly the best sword and sorcery ever written, but some of the stories do not have strong horror elements, or only touches of them. I think the question becomes, what is horror? To me horror is more about the atmosphere, and the definition by the Horror Writer’s Association seems workable (rather ironic, considering that much of what is called modern horror seems to be only sadism and gore).

Good article, Fletcher! Thanks for taking the time to write it.

Actually, what I think is more essential to Sword and Sorcery than horror is a sense of mystery (not meaning mystery as in “a mystery,” like one found in a crime novel). Of course, this will often result in fear of the unknown, and this is where horror might come in. My story, The Blue Lamp in Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, has mystery, but not sure if it would qualify as having horror. In your review, Fletcher, you called it sword and sorcery, as others have. I have been using that label myself in the trailers for the dramatization of the story. But I also call it heroic fantasy. Six of one…

@Aonghus – I agree that S&S is easier to know by reading than by definition. Definitions can be straitjackets. Every S&S story needn’t be horror, but the possibility of the malign supernatural’s existence in said story’s world should be possible.

@James – Grisliness is just gore and S&S needs more than that. Then you’re just treading Eli Roth territory and I’m unwilling to admit that stuff into my horror club. 😉 I haven’t read Abercrombie, but my impression is he’s writing epic fantasy from a cynical perspective, but not S&S. Same for GRRM and other, similar, writers.

@Raphael – I consider it very important, but as I wrote just wrote, it need only be present in the sense of being possible. Of course, I do prefer it when it makes a big, bold center stage appearance.

@darkman – Agree with pretty much all that. And then I remember the creepy, central plot in Cook’s Shadows Linger – very horrific.

@Charles Martel – I agree it’s mostly not S&S, but very, yeah, very, very horrific.

@RobertZ – Thank you. Mystery’s good, but I want my S&S world to be more haunted than mysterious. As to heroic fantasy vs. swords & sorcery, I use them interchangeably myself.

Excellent post.

It is worth nothing that Fritz Leiber said, when asked about his earliest Fafhrs & Gray Mouser stories, that he never wrote them as fantasy, he always wrote them as supernatural horror.

I’d also point out that sword & sorcery always seem to classify the supernatural as extraneous, dangerous and somewhat sick. The best cure for a sorcerer is a span of cold steel in the ribs.

While living in a world filled with supernatural, the characters in s&s still can’t consider it “normal” or acceptable. It is always disruptive, scary and creepy.

Once again, a clear connection with supernatural horror, I think

(and here I stop my rambling)

I don’t remember where I first read it, but one very interesting description I’ve seen for Sword & Sorcery is “encounters with the supernatural”. Which covers both the horrific and mystery.

I am not a big Leiber fan, but those stories I remember fondly do have clear horror elements. The Sunken Land is probably my favorite, but Claws from the Night was also fun. Creepy fun.