Fantasia 2016, Day 11, Part 2: Devils and Heroes (If Cats Disappeared From the World and Superpowerless)

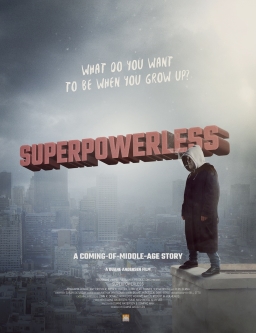

Impossible to predict some things. Notably: you can’t know how you’ll react to a work of art until you’ve experienced it. Looking at the movies Fantasia offered on Sunday night, July 24, I thought I’d try If Cats Disappeared from the World (Sekai kara neko ga kietanara), which promised a tale about a terminally ill man who makes a surreal Faustian bargain. After that, I decided I should watch Superpowerless, as it was a genre piece about an aging superhero who’d lost his powers. In truth, I had my doubts about both movies; Cats looked it might suffer from excess of romanticism and forced whimsy, while Superpowerless seemed like some kind of mumblecore satire treading ground comics had worked over decades past. In the event, I was wrong to doubt. If Cats Disappeared from the World would be likely the best movie I saw at Fantasia, and probably my favourite. Superpowerless, meanwhile, turned out to be the festival’s most pleasant surprise, the film which most greatly exceeded all my expectations.

Impossible to predict some things. Notably: you can’t know how you’ll react to a work of art until you’ve experienced it. Looking at the movies Fantasia offered on Sunday night, July 24, I thought I’d try If Cats Disappeared from the World (Sekai kara neko ga kietanara), which promised a tale about a terminally ill man who makes a surreal Faustian bargain. After that, I decided I should watch Superpowerless, as it was a genre piece about an aging superhero who’d lost his powers. In truth, I had my doubts about both movies; Cats looked it might suffer from excess of romanticism and forced whimsy, while Superpowerless seemed like some kind of mumblecore satire treading ground comics had worked over decades past. In the event, I was wrong to doubt. If Cats Disappeared from the World would be likely the best movie I saw at Fantasia, and probably my favourite. Superpowerless, meanwhile, turned out to be the festival’s most pleasant surprise, the film which most greatly exceeded all my expectations.

If Cats Disappeared from the World, which played the large Hall Theatre, was directed by Akira Nagai and written by Yoshikazu Okada from a bestselling novel by Genki Kawamura. It follows a young postman (Takeru Sato, of Rurouni Kenshin fame) who as the film opens is diagnosed with an incurable brain tumor. His death could come at any moment, the doctor tells him, but when he returns home he’s met with a double of himself who is, evidently, the devil; and the devil guarantees the unnamed postman he’ll die tomorrow. There is another option, though. The devil will give the mailman another day of life if the postman will allow the devil to remove a given thing from the world, retroactively changing events so that the thing never existed — removing as well all memories and feelings to do with that thing. Every day the devil will take another thing from the world, with each thing taken giving the postman another day of life. He agrees, and the devil announces the first thing he’ll take: telephones. Which, we soon see, is a problem as the postman’s ex-girlfriend (Aoi Miyazaki), the great love of his life, met him due to a wrong number.

It’s worth pointing out that this isn’t a detailed alternate-history movie. The film doesn’t waste time imagining a world without the history of telephony and the internet and so forth. The key is the mailman’s life, and the crucial elements thereof. The movie unfolds in the present and in a set of nested flashbacks, which we come to understand better and better as the film goes on, each scene deepening the previous ones and explaining more and more of what we saw. It’s a complex, masterfully executed structure. Past and present scenes are balanced perfectly, with the narrative never losing pace as we move further back into the postman’s life and see the complex web of relationships that his life-saving devil is gleefully shredding.

It’s worth pointing out that this isn’t a detailed alternate-history movie. The film doesn’t waste time imagining a world without the history of telephony and the internet and so forth. The key is the mailman’s life, and the crucial elements thereof. The movie unfolds in the present and in a set of nested flashbacks, which we come to understand better and better as the film goes on, each scene deepening the previous ones and explaining more and more of what we saw. It’s a complex, masterfully executed structure. Past and present scenes are balanced perfectly, with the narrative never losing pace as we move further back into the postman’s life and see the complex web of relationships that his life-saving devil is gleefully shredding.

The character work in this movie is phenomenal. The structure’s perfectly imagined to give us an in-depth examination of a man and the history of his life, and Okada and Nagai exploit it wonderfully. Transitions from past to present deepen emotions, creating layers of meaning in a given moment. The effect is unutterably moving, but also used intelligently. A simple scene of the postman watching Metropolis on TV and answering a phone call that turns out to be the wrong number is affecting when we first realise that this is where he meets his former girlfriend; then it becomes even more so, when we learn that the postman’s closest friendship is with a film fanatic (Gaku Hamada, who nearly steals the movie) who works at a video store and lends him a different movie every day so that he can educate himself about cinema — and at this point we understand why he was watching Metropolis, and the already-effective scene gains another emotional tint and develops more power. And then, of course, we learn that the second thing the devil wants to take from his life is cinema.

Each time the devil takes something from the world, the postman gets one last day before it goes away forever, a last day to say his farewells to what he’s losing. The film thus centres itself around loss and the sense of loss: this is not a movie about a man desperately doing everything in his power to stave off death, but a film about a man watching all that he is slowly dissolve, and pondering what compromises he will accept for the sake of life. It’s a film of sadness and grief, one that seeks some kind of acceptance, a final peace. The ending is perfectly equivocal, as the postman reaches that equilibrium and reconnects with with someone important in his life. The film does not preclude the possibility that the devil was wrong and that he will survive, but neither does it suggest anything of the sort. The viewer’s at liberty to imagine either ending, or, like the postman himself, to accept uncertainty and equilibrium and the present moment.

Each time the devil takes something from the world, the postman gets one last day before it goes away forever, a last day to say his farewells to what he’s losing. The film thus centres itself around loss and the sense of loss: this is not a movie about a man desperately doing everything in his power to stave off death, but a film about a man watching all that he is slowly dissolve, and pondering what compromises he will accept for the sake of life. It’s a film of sadness and grief, one that seeks some kind of acceptance, a final peace. The ending is perfectly equivocal, as the postman reaches that equilibrium and reconnects with with someone important in his life. The film does not preclude the possibility that the devil was wrong and that he will survive, but neither does it suggest anything of the sort. The viewer’s at liberty to imagine either ending, or, like the postman himself, to accept uncertainty and equilibrium and the present moment.

For that’s also a theme in the movie, accepting the present. Not with a simple insistence on living in the now, I think, but with a reminder that the future is uncertain and the past is made of memories that slip away from us: the present is what we have and must accept. A flashback to a trip to Buenos Aires (in which the postman and his girlfriend meets a man punningly named Tom) makes the point effectively.

This is not an argument to abandon oneself to sensation, I think, given how much the film also celebrates the joy of watching movies. It’s very much a film about films, and indeed a film in love with films. Cinematic reality and cinematic references blur. The postman’s ex-girlfriend works in a movie theatre, and one of the films there early on amusingly foreshadows the relationship between the postman and his devil. “You’re never really done for as long as you’ve got a good story and someone to tell it to,” we’re reminded, a quote from Giuseppe Tornatore’s The Legend of 1900. This is a story about stories, then, a story about the stories that make up our lives, and how they’re all connected.

Visually, the camera finds subtle beauty in a kind of attractive clutter, whether in the postman’s apartment or an over-full video store. It seems to relate to the movie’s theme of things slipping away; here are concrete things, things everywhere, relating one to another. While there are cats in this movie, they don’t dominate the screen but are as it were deployed carefully. They’re a part of the postman’s life, but like everyone else in his life, not simply there in themselves but part of the web of people and events that make him who he is. There is a reason for them to be there, but not the one you might expect at first.

Visually, the camera finds subtle beauty in a kind of attractive clutter, whether in the postman’s apartment or an over-full video store. It seems to relate to the movie’s theme of things slipping away; here are concrete things, things everywhere, relating one to another. While there are cats in this movie, they don’t dominate the screen but are as it were deployed carefully. They’re a part of the postman’s life, but like everyone else in his life, not simply there in themselves but part of the web of people and events that make him who he is. There is a reason for them to be there, but not the one you might expect at first.

The movie could be called a tearjerker, but I’m reluctant to use the word; it seems to slight the intelligence, like a watchmaker’s precision, that underlies the playing-about with time and structure and emotion. It’s a heartbreaker, let’s say, thoughtful and mournful and hopeful all bound up together. It unites a perfection of structure with a perfection of imagery and tops it off with a tasteful and perfect ending. There’s a deep humanism to the movie, and a wondrous consciousness of cinematic form. It’s not, in the end, technically a genre piece; nor am I sure whether it has the religious overtones it would appear to, for all that it’s easy to see certain images as having a symbolic dimension (hard not to notice that the postman’s father is a watchmaker, especially in a film so fascinated by time and flashbacks). It’s a movie about this world, and the loss of it. And it is wise and courageous and honest.

I left the Hall Theatre deeply satisfied, and then increasingly nervous. The trailer I’d seen for the next movie, Superpowerless, suggested it was a satire of a fairly shallow kind. I wasn’t sure at all sure how well it’d follow Cats. In fact, I needn’t have worried. Superpowerless turned out to be itself a film of considerable integrity and humanism.

It follows a middle-aged couple, Bob (Josiah Polhemus) and Mimi (Amy Prosser). It just so happens that Bob used to be a superhero, Captain Truth. His powers have faded with age, and while Mimi’s career is taking off, he’s no longer sure what he should be doing with himself. Mimi suggests he write a book of memoirs, and find a freelance editor to help him shape it into something saleable. Bob takes her advice, and begins recording his thoughts and reflections, hiring young editor Danniell (Natalie Lander) to help. But the editor’s increasingly drawn to him, while Mimi seems to be drawing away. Will Bob regain his powers? If he does, will he still be a hero? Or even a good man?

It follows a middle-aged couple, Bob (Josiah Polhemus) and Mimi (Amy Prosser). It just so happens that Bob used to be a superhero, Captain Truth. His powers have faded with age, and while Mimi’s career is taking off, he’s no longer sure what he should be doing with himself. Mimi suggests he write a book of memoirs, and find a freelance editor to help him shape it into something saleable. Bob takes her advice, and begins recording his thoughts and reflections, hiring young editor Danniell (Natalie Lander) to help. But the editor’s increasingly drawn to him, while Mimi seems to be drawing away. Will Bob regain his powers? If he does, will he still be a hero? Or even a good man?

Directed by Duane Andersen, and written by Andersen with Dominic Mah, the movie’s a rare mix of comedy and drama; its humour is understated yet funny, while its characters tell a human story about truth and aging. I’ve seen a lot of stories over the years about superheroes who’ve lost their powers. Some of them — Alan Moore’s Marvelman, some story arcs of Astro City — have used middle-age as a way to complicate the hero’s lives. This is probably the first time I personally have seen a movie about a middle-aged couple whose lives are complicated by superheroism. The superheroic aspects are definitely present, but this isn’t a hard-core genre piece: there aren’t any supervillains in this world, and few other heroes with powers. There’s only one gag that relies on what you might call superhero traditions, and a plot question near the end that’s enhanced by knowing the conventions of the genre (though they’re not required). Bob’s past is something of a metaphor, but an effective one.

I’d say it’s effective because it’s also a key part of who he is. He’s a genuinely nice man who instinctively wants what’s best for everyone and tries to be as good as he can. At the same time, the movie’s clever enough to question Bob’s morals. Was Bob-as-superhero really that good a man if he often used violence? Was he a good man when he knew he wasn’t in danger in a fight? Or is it enough that he went out and tried to do right in the world?

Crucially, the movie’s at least as interested in Mimi as it is in Bob. She has a character arc of her own, shaped by her own decisions, that runs in parallel with Bob’s and intersects with it in clever ways. Would a superhero really be the easiest person in the world to live with? Almost in passing we note that Bob’s a vegetarian, while Mimi refrains from eating meat for his sake but has no qualms about tucking in to a meat-filled meal when she’s with her co-workers. If Bob’s struggling with physical limitations that come with age, Mimi’s wondering about the shape of her life and career and what she wants as she grows old. The two of them often turn to each other, but aren’t always entirely open, in part because they don’t want the other to think less of them.

Crucially, the movie’s at least as interested in Mimi as it is in Bob. She has a character arc of her own, shaped by her own decisions, that runs in parallel with Bob’s and intersects with it in clever ways. Would a superhero really be the easiest person in the world to live with? Almost in passing we note that Bob’s a vegetarian, while Mimi refrains from eating meat for his sake but has no qualms about tucking in to a meat-filled meal when she’s with her co-workers. If Bob’s struggling with physical limitations that come with age, Mimi’s wondering about the shape of her life and career and what she wants as she grows old. The two of them often turn to each other, but aren’t always entirely open, in part because they don’t want the other to think less of them.

The quasi-romance between Bob and Danniell is particularly well-handled, with an unobtrusive but quite welcome restraint. There’s just enough chemistry there to make you really wonder what Bob will do, even if you’re pretty sure how it’ll play out. In fact I’d say one of the things Superpowerless does that many much bigger-budget superhero movies have failed to do is find a way to get real dramatic mileage out of the internal conflicts of a character who is basically good; a more difficult task than it sounds. The Captain America movies are the closest thing I can think of in that sense, and even there you don’t feel that Cap’s genuinely tempted to go over to the bad guys — he’s never as beaten down as Bob, and so doesn’t suffer like him and doesn’t face the same temptation to (perhaps) relieve that suffering.

Conversely, the movie does an excellent and understated job of showing Mimi’s growth throughout in a different key. It’s a typically fine touch that she’s the one who suggests Bob get himself an editor — she’s the one who sees a kind of practical solution to his situation. That kind of perception leads to her career beginning to take off; but does she want something else? “Who wants to bring a child into a shithole world like this?” wonders Bob in one of his bleaker moments. But what does Mimi want for them? For their future?

Conversely, the movie does an excellent and understated job of showing Mimi’s growth throughout in a different key. It’s a typically fine touch that she’s the one who suggests Bob get himself an editor — she’s the one who sees a kind of practical solution to his situation. That kind of perception leads to her career beginning to take off; but does she want something else? “Who wants to bring a child into a shithole world like this?” wonders Bob in one of his bleaker moments. But what does Mimi want for them? For their future?

Polhemus as Bob and Prosser as Mimi bring out the subtleties and nuances of their characters’ relationships perfectly. There’s a good argument that their performances were the best I’d see this year at Fantasia, defining their characters and moving them through a well-realised arc. Polhemus as Bob is the most credible superhero (or former superhero) I’ve seen on film in a while — even though he never does anything superhuman. In the way he moves and especially in the way he smiles, in the kindness of his expression, there is the sense of what you want to see in a superhero, a man confident in his power and who acts out of pure goodness. At the start of the movie he doesn’t smile much, though, beaten down by life — so when we do see that grin, it’s almost magical.

Where does it fit among the canon of superhero films? For me, it may be the best film superhero story I’ve seen that doesn’t use pre-existing comics characters (though I’m a long way from having seen them all). It handles its metaphors in an unusual way, avoiding the costumes and fight scenes that one normally associates with superhero stories. But there’s no doubt that a superhero story is what this movie is, one with intelligence and craft.

Where does it fit among the canon of superhero films? For me, it may be the best film superhero story I’ve seen that doesn’t use pre-existing comics characters (though I’m a long way from having seen them all). It handles its metaphors in an unusual way, avoiding the costumes and fight scenes that one normally associates with superhero stories. But there’s no doubt that a superhero story is what this movie is, one with intelligence and craft.

A question-and-answer session followed the film with director Duane Andersen (who I’d seen before the movie started, when he came out and high-fived everybody in line) and stars Josiah Polhemus and Amy Prosser. According to my notes (as always, handwritten and thus not as reliable as I’d like) the interviewer began by asking Anderson to recount the history the three of them had together, and Anderson explained that he and Polhemus had known each other since first grade and dreamed of making movies (a shot from one of their first films turns up at the end of Superpowerless). They met Prosser when they were 12, the same age Bob and Mimi met in the film. Polhemus moved away at 14, then they met up again recently. Polhemus and Prosser married each other a few years ago, and all of this history is paralleled by their characters onscreen. The film’s partially autobiographical, incorporating places from their lives as settings.

Asked why he’d done a superhero story, Andersen said that he was a fan and after reconnecting with Polhemus about a decade ago, he’d wanted to see what Polhemus could do with the role of a superhero without powers. The actors were asked how they felt their being in a relationship affected their work onscreen, and Prosser began by noting that Superpowerless was her first movie ever after having done a lot of work on stage. Working with Polhemus was very comforting, she said; her first days were scenes in bed with her husband. She said it was good to work with him as an actor she trusted. Polhemus said he’d been nervous as the film was shot in their real house. He was worried about having the film crew living and shooting with them, but ended up enjoying it a lot. He just had to react to what Prosser gave him, “which,” he said, “is very full.”

Asked why superhero movies are so successful now, Andersen admitted that it was beyond him to answer that, and also admitted to being just a little tired of them. He didn’t just want to do a superhero movie, which was why he consciously didn’t show Bob’s costume or a big fight. His writing partner, he said, was more of a fan, and Andersen said he had to keep reeling him back in. Polhemus observed that the story was the focus in Superpowerless in a way unlike most superhero movies; he also said (what I don’t believe I’ve ever heard anyone say before) that he was most interested in the origin sequences in superhero films. Andersen observed that the prevalence of superhero movies showed that comic geeks were now in charge.

Asked why superhero movies are so successful now, Andersen admitted that it was beyond him to answer that, and also admitted to being just a little tired of them. He didn’t just want to do a superhero movie, which was why he consciously didn’t show Bob’s costume or a big fight. His writing partner, he said, was more of a fan, and Andersen said he had to keep reeling him back in. Polhemus observed that the story was the focus in Superpowerless in a way unlike most superhero movies; he also said (what I don’t believe I’ve ever heard anyone say before) that he was most interested in the origin sequences in superhero films. Andersen observed that the prevalence of superhero movies showed that comic geeks were now in charge.

Asked about the definition of Bob’s power, Andersen said that for this movie he discovered his power as a human. Polhemus said that he liked the story of Mimi, the story of someone with strength of character helping a friend. Prosser also emphasised the theme of not giving up on one’s dreams. Polhemus observed that it takes a certain courage as an older person to put oneself on screen. Another questioner liked the specificity of the San Francisco setting, and the use of local actors, and Andersen talked about casting friends in minor roles; he noted in response to another question that one role in the scene, an artisan who makes birdhouses, was a real person who he wrote into the movie.

A questioner asked about the use of Kickstarter in funding films, and Andersen expressed some misgivings, noting that it takes a lot out of you. It’s stressful process that can become a full-time job in itself. Finally, a questioner asked about a Canadian flag seen in a minor character’s office; Andersen said that the crew had simply shot that scene in a real office that they’d been allowed to use, and it so happened that the person whose office it was had been Canadian. The character in the film was a jerk, which the filmmakers didn’t care about until their film was accepted in a Montreal film festival — at which point they decided the character was probably from Vancouver.

That ended the night. It had been a good day on the whole, with a powerful one-two punch to end it all. It was a wonderful day of genre film, covering a range of tones. Neither If Cats Disappeared from the World nor Superpowerless are standard genre pieces, but both show the complexity that genre ideas can bring to character and structure — and the way fiction can illuminate real life. They’re also both wonderful movies. I’m glad I got to see them both.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.