Fantastic, November and December 1963: A Retro-Review

|

|

I recently looked at a couple of issues of Fantastic with a Brak the Barbarian serial by John Jakes, and here’s another pair with a Brak serial. Indeed, this was Jakes’ first SF/Fantasy novel, and his second Brak story.

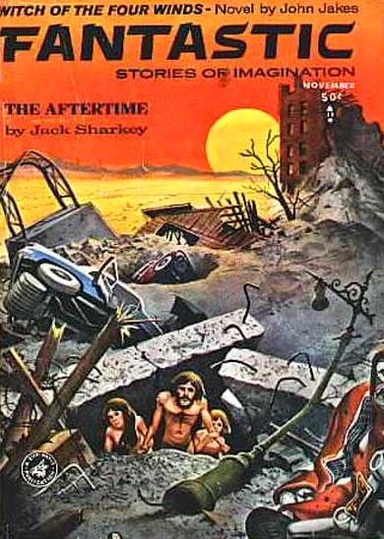

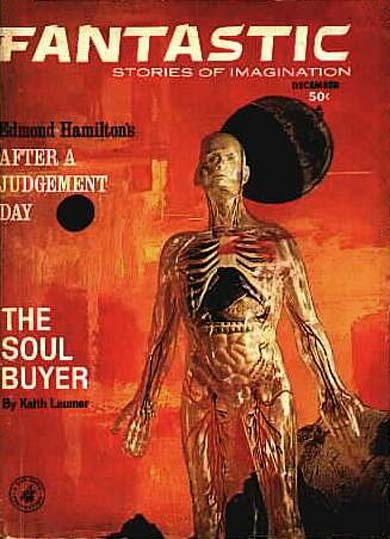

The editorials cover first, Freeman Dyson’s ideas about using gravity as an energy source (for transportation), and second, the notion of having astronauts use crayons in orbit. The covers are by Alex Schomburg (November) and Paul E. Wenzel (December), in neither case, perhaps oddly, illustrating Jakes’ novel. Interiors are by Lee Brown Coye, Virgil Finlay, and Peter Lutjens (each of them appeared in both issues). (I will note that I find Coye okay as a pure horror illustrator, which seems to have been his forte, but I thought his illustration for Jack Sharkey’s “The Aftertime” just terrible.)

There is a letter column in November (Fantastic’s lettercol, which only appeared occasionally at this time, was called According to You ...). The letters this time are by David T. Keil, Paula Crunk, and Dennis Lien. I’ve known Denny online for quite some time, first on Usenet and later via email, so that was interesting. Keil has praise for Keith Laumer and Brian Aldiss and Thomas Disch, some (generally positive) discussion of Fritz Leiber, and scorn for David R. Bunch. Paula Crunk is happy with Leiber and Laumer, but complains about some of the other dreadful stuff the magazine published. And Lien disputes a claim in an earlier letter that fantasy has gotten short shrift in Hugo nominations relative to SF. (He notes the several examples of fantasy that were nominated — 3 at least of the five short fiction nominees the previous year — and also notes that, after all, the Hugos are given at a “Science Fiction” convention.)

The stories, then:

November

Serial:

Witch of the Four Winds, part 1 of 2, by John Jakes (22,700 words)

Novelets:

“The Aftertime,” by Jack Sharkey (9,900 words)

“‘I, I, I} was a Spider for the SBI’,” by Neal Barrett, Jr. (10,800)

Short Stories:

“Darkness Box,” by Ursula K. Le Guin (2,200 words)

“And on the Third Day,” by John J. Wooster (500 words)

December

Serial:

Witch of the Four Winds, part 2 of 2, by John Jakes (23,300 words)

Novelets:

“Lilliput Revisited,” by Adam Bradford, M. D. (10,100 words)

“The Soul Buyer,” by Keith Laumer (11,000 words)

Short Story:

“After a Judgement Day,” by Edmond Hamilton (4,700 words)

As I said last time: John Jakes (b. 1932 in Chicago) began publishing SF as a teenager in 1952. He labored in the traditional pulp fields (SF, mystery, Westerns) for the next 20+ years, also publishing historical novels as by Jay Scotland, and doing some advertising work.

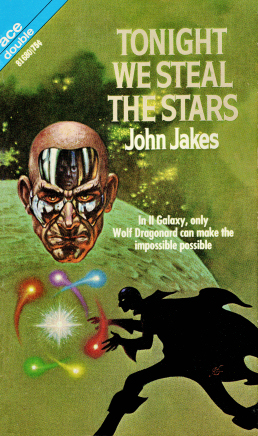

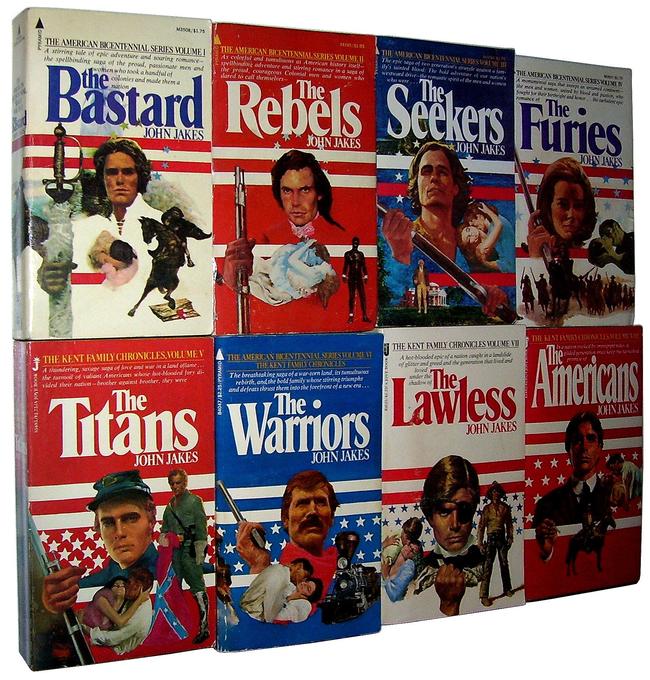

His first SF novels were the Dragonard space opera series beginning in 1967 (When the Star Kings Die, The Planet Wizard, and Tonight We Steal the Stars), and his best known SF novels is probably the satirical On Wheels (1973), set in a future where everyone lives in cars that can never go slower than 40 mph. But his career took off with the enormous success of his Kent Family Chronicles, historical novels about the Revolutionary War, their release timed to coincide with the Bicentennial. Since then he’s concentrated on historical fiction, with continued success.

His first SF novels were the Dragonard space opera series beginning in 1967 (When the Star Kings Die, The Planet Wizard, and Tonight We Steal the Stars), and his best known SF novels is probably the satirical On Wheels (1973), set in a future where everyone lives in cars that can never go slower than 40 mph. But his career took off with the enormous success of his Kent Family Chronicles, historical novels about the Revolutionary War, their release timed to coincide with the Bicentennial. Since then he’s concentrated on historical fiction, with continued success.

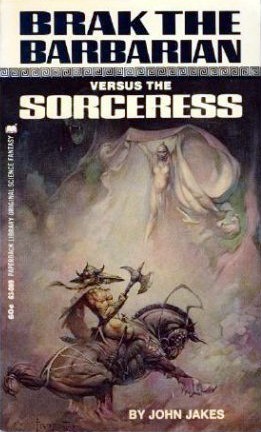

“Witch of the Four Winds,” as I noted, was the first Brak the Barbarian novel (and second story), though it didn’t become a book until 1969, the second Brak novel in book form. The book was called Brak the Barbarian versus the Sorceress. Brak comes into a land once fertile that now seems blasted. After rescuing a shepherd girl from a monster called the Manworm, he makes his way to the ruling city, and old Lord Strann, who seems to be a good man, if aging, with a fine son and heir, who seems very concerned with the welfare of the peasantry.

But they are threatened by a local woman named Nordica, and her companion, the “Magian” (i.e. wizard) Tamar Zed. Nordica is believed to have killed her father, and stolen his secret of turning base metal into gold. She has lured away most of Strann’s army with promises of riches. Brak tries to help Strann, and is captured by Nordica, to be one of four human sacrifices at the rite that will facilitate the transmutation. His fellow sacrifices are the very shepherd girl he had rescued earlier, as well as an old seaman, and a treacherous smith. (For some very annoying reason, Jakes keeps calling the smith a “smithy,” as if he didn’t know the difference between the man who works metal and the facility in which he works.) Naturally, escape attempts follow, along with betrayals, and further encounters with the Manworm, and with Nordica’s enchanted beast, Scarletjaw … but Brak prevails. (Sorry about the spoiler!)

One other thing I noted — consistent with other stories about him I’ve read — Brak seems very uninterested in women. Unlike Conan in that sense. In this case he refuses the grateful advances of the shepherd girl and pushes her at the young prince. (Noble of him, no doubt, but executed in a way that makes him seem really uninterested, not just chivalrous.) All in all it’s a pretty minor piece of derivative Sword and Sorcery, and rather carelessly written. The other Brak stories I’ve read, while hardly masterworks, do seem to show Jakes getting a bit better.

November short fiction:

“The Aftertime,” by Goldsmith regular Jack Sharkey, begins as a very straightforward post-apocalyptic story, with a young man, Rory, waking to find his city bombed and his building mostly collapsed. He wanders the city, encountering a young woman and then a few more people, eating canned food, banding together for help, but slowly losing hope as nothing is heard on the radio, and then people start dying because of some strange energy organism. Then there’s a shocking twist (*spoiler below – I don’t think many people care too much about minor half-century old stories, but just in case) – it fooled me – and a quite strained ending concerning the less than plausible (to say the least) nature, origin, and weakness of the energy beings.

“The Aftertime,” by Goldsmith regular Jack Sharkey, begins as a very straightforward post-apocalyptic story, with a young man, Rory, waking to find his city bombed and his building mostly collapsed. He wanders the city, encountering a young woman and then a few more people, eating canned food, banding together for help, but slowly losing hope as nothing is heard on the radio, and then people start dying because of some strange energy organism. Then there’s a shocking twist (*spoiler below – I don’t think many people care too much about minor half-century old stories, but just in case) – it fooled me – and a quite strained ending concerning the less than plausible (to say the least) nature, origin, and weakness of the energy beings.

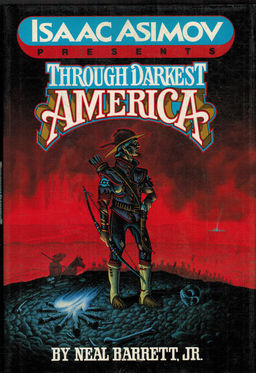

Neal Barrett, Jr. (1929-2014) began publishing SF with stories published more or less simultaneously in the August 1960 issues of Galaxy and Amazing, so he was either (or both) a Gold (and Pohl?) discovery or a Goldsmith discovery. That said, he also worked for the Stratemeyer Syndicate, publishing as by Victor Appleton and Franklin W. Dixon, so presumably he wrote both Tom Swift stories and Hardy Boys stories, though I don’t know when. His early work was decent but not particularly special, but in the 80s and through the 90s he published some excellent novels (most notably Through Darkest America) and stories (my favorite being “Stairs”). Later he turned to mysteries of a somewhat gonzo tone, like Pink Vodka Blues. He was SFWA Author Emeritus in 2010.

“I I I} was a Spy for the SBI” (the I’s are supposed to be arranged vertically) is comic but not really gonzo, about three operatives for the Special Bureau of Investigation, two guys and the woman they both have the hots for, who are assigned to infiltrate a building on an alien planet and figure out how to close a deal with the spider-like and privacy-obsessed locals. They do so by operating, all three at once, a giant spider suit. It’s enjoyable enough light comic SF, nothing special but OK of its sort.

John J. Wooster published only two stories, both in 1963 issues of Fantastic. “On the Third Day,” as its title suggests, is about the Resurrection, positing that Jesus was an alien visitor, and adding a tiny twist. Minor indeed, but then, it’s only 500 words long.

And finally, “Darkness Box” is, not surprisingly as it’s by Ursula K. Le Guin, the best story in the issue. It’s her third professionally published story (though she had an earlier and quite good story in the Western Humanities Review) — all her early work was bought by Cele Goldsmith. This is a moral fable, a mode to which Le Guin would return several times. It’s about a young prince who fights a battle every day with his treacherous brother. But it opens with a boy finding a box in the ocean, and giving it to his Mother, a witch, who in turn gives it to the prince. Against his father’s wishes, he opens the box — well, we know what’s in it (the title tells us), and what that means. The message may be a bit obvious, but the story still stands out for the already elegant prose.

I previously covered one of Adam Bradford’s modern day Gulliver stories. These stories, actually written by Joseph Wassersug, posit that Adam Bradford, M. D., discovers during his medical research that Jonathan Swift was actually plagiarizing a real account by Lemuel Gulliver of his actual travel. Bradford manages to find his way to these actual places. “Lilliput Revisited” is the first of the series (which comprises four stories). We see Bradford discovering the Gulliver manuscript, and some artifacts (like tiny clothes) that seem to support the notion that Lilliput etc. are real places. He buys a yacht and goes to Lilliput, only to be stuck there for lack of fuel. He is received fairly well there, and the rest of the story describes the changes in Lilliputian society since Gulliver’s time: they are now a democracy, and have conquered neighboring Blefuscu. The issue of which end of the egg to open is no longer important: the new controversy is which shoe to put on first. Lilliputian medicine is described, and their government, which depends on officials being brainwashed into nonviolence. It’s never very convincing, and there’s no real plot. Though I thought the previous example I read somewhat heavy-handed, at least it had a point — this story just rambles on until “Bradford” is able to refuel his yacht and move on.

Keith Laumer’s “The Soul Buyer” is one of his Niss stories. It’s about a gambler who has been remarkably lucky since an old man gave him a tip. He gets bored with winning all the time and tries to track down the old man, and finds a mystery, related to his unusual “agent” — and related eventually to the inimical Niss, and to an alien species even the Niss serve … Decent early Laumer, though not among his best work.

And finally “After a Judgement Day,” by the great veteran Edmond Hamilton. This is set on a space station, where a couple of people survive, after the human population on Earth has succumbed to plague. The station’s job is to wait for the return of the unmanned interstellar probes that were sent before the plague came — perhaps they are the only hope for humanity. The two survivors clash over whether to stay on the job and wait for the probes — none of which has been truly a success yet; or return to near certain death but a sort of peace. The resolution is pretty effective, really.

*Spoiler for Jack Sharkey’s “The Aftertime” – it turns out this is an experiment run by the Army – they’ve recruited a few volunteers to live through a simulated post-Apocalypse scenario.

Our recent coverage of Fantastic includes:

December 1959

April 1960

January 1962

February 1962

June and July 1962

November and December 1963

January and February 1964

August and September 1964

October 1964

January 1965

June 1965

Fantastic Stories: Tales of the Weird & Wondrous, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Patrick L. Price

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a Retro-Review of the May 1963 issue of Amazing. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. See all of Rich’s retro-reviews here.

Interesting about the ending you mention for “The Aftertime” since that is basically the plot of the pilot for the Twilight Zone. Although that episode would have been filmed in 1959 (or perhaps even as early as 1958) I don’t believe it ever actually aired. I discovered it on a VHS tape called Treasures from the Twilight Zone in the mid-90’s. Of course that reflects the whole Cold War post-McCarthy mindset, so there were probably other similar stories with basically the same plot, and probably even a few others were published.

Rich, I’d like to thank you particularly for taking the time to say something about the letters section.

Would you do me a favor and write up issue(s) of Fantastic that had material relating to Tolkien and Peake? I know that the issue with Ballard’s “Singing Statues” has a longish [for the magazine] letter from Michael Moorcock about the ailing Mervyn Peake, because I have owned a copy of that issue for many years (July 1962). I think there was a little more on Peake around that time, and something on Tolkien too, in the letters columns. Thanks.

I have just read the issue with Moorcock’s letter about Peake … I will write it up soon and look for the other issues from that period that might have more about Tolkien/Peake.

Thanks!

Amy … yes, that does seem a very Twilight-Zonish idea (“The Aftertime”, that is) … I had no idea about the existence of that pilot. Thanks!

I’m really looking forward to your write-up. Mentions in the magazines must have been of great importance back then, in getting the word out about such books, which (I suppose) small bookstores and gift shops wouldn’t have been likely to carry. For decades it would have been primarily the magazines that let people know about the existence of fandom. How exciting to learn of books such as Tolkien’s and Peake’s, and of other people who liked to read such things.