When Researching Your Novel Scares You: Daily Life in the Third Reich

Propaganda photo of the Volkssturm. This civilian militia appears

to be well armed, but in fact borrowed their weapons from a regular

army unit and had to give them back after the parade. The Volkssturm

received castoff uniforms or no uniforms at all. The most appropriate

uniform would have been a big bulls-eye on their chest

I’m in the process of researching one of my upcoming novels, Volkssturm, about the German civilian militia formed in October 1944. The Volkssturm called up all able-bodied men aged 16 to 60 who weren’t already in uniform. It also brought in some women. Most of these people weren’t particularly fit, or had been working in essential jobs such as armament factories and had been made redundant due to chronic shortage of material and Allied bombing. Even those who remained in essential jobs often served in local Volkssturm units charged with protecting their home area. The idea was to launch “total war” against the Allied invaders and save the homeland from devastation. We all know how well that worked out.

A female member of the Volkssturm learning how to use a Panzerfaust,

an early form of rocket propelled grenade. Due to a shortage in

weapons and ammunition, most recruits got little training

I’m intrigued by the story of the Volkssturm because these were people who had spent more than a decade living under Hitler’s rule but had managed to avoid facing the war directly. Now the war had come home to them, and they were given a weapon and told to fight.

None of my three protagonists is an ardent Nazi. They all dislike the government to various degrees and just want the war to be over. But with the Allies closing in, how do they react? How would we?

To figure that out, I’ve been researching civilian life in the Third Reich. What I’ve found is that the Nazi party had an even stronger stranglehold on their populace than I suspected.

Freedom of speech, movement, and association was curtailed in any number of ways. Collusion with the government was pretty much mandatory. For example, you couldn’t expect to get far in your career if you weren’t a member of the Nazi Party. Most professional jobs actually required memberships. But working class people didn’t get away from it either. When Hitler disbanded all trade unions after coming to power, he created an umbrella organization called the Arbeitsfront (“Labor Front”), a vast union for all workers. Good luck getting a job if you weren’t a member. If you already had a job when it was formed, you could avoid membership, but you couldn’t expect to get promoted.

The Nazis, of course, made a ton of money off the membership fees.

Another scam was the Winter Relief Fund, which was supposed to help impoverished Germans during the winter months. Instead the money went to the war effort and to party members. Donors to the Winter Relief Fund got an armband or pin depending on how much they gave. Those who didn’t give, of course, would be just as visible. Everyone knew it was a scam, but wouldn’t you be tempted to give just a little in order to avoid getting stopped by the Gestapo in the street and asked why you didn’t support fellow Germans in need?

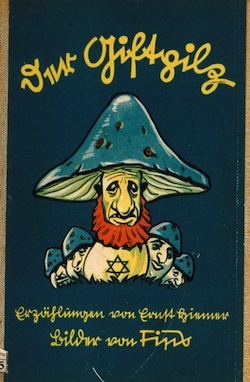

If you had children you’d be in an even tougher situation. Imagine your eight-year-old daughter comes home from school one day with a new book. It’s called The Poisonous Mushroom and is all about how Jews are poisoning Germany. It contains lines like:

If you had children you’d be in an even tougher situation. Imagine your eight-year-old daughter comes home from school one day with a new book. It’s called The Poisonous Mushroom and is all about how Jews are poisoning Germany. It contains lines like:

Just as a single poisonous mushroom can kill a whole family, so a solitary Jew can destroy a whole village, a whole city, even an entire people.

Being a decent person, you object to this. But if you complain to the school, they’ll denounce you to the Gestapo and you and your spouse will end up in a concentration camp. Your daughter will be sent to a Nazi orphanage to be brought up “correctly.” Of course you could have a private chat with your daughter about how wrong this book is, but what if she lets that slip in the playground? What do you do?

An excellent documentary on this dilemma is Hitler’s Children, a gripping series that looks at the rise of the Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls. There are some fascinating interviews with former members about how the camaraderie, outdoor activities, and good food were a real attraction to poor urban kids and you can still see a glint of nostalgia in some of these old people’s eyes. Watching the old films of the Hitler Youth camps, I could see how if I was a child back then I would have wanted to join. I always wanted to go to a sleep-away camp as a kid — hiking in the woods, shooting and canoeing, songs by the campfire, new friends. Sounds great.

The holiday didn’t last long. Membership was at first encouraged, then demanded, and finally mandatory. Kids were encouraged to beat each other up in order to establish a pecking order and toughen themselves for the war. Activities got to be longer and longer, until a child would spend all day at school, then all evening and the weekend in the Hitler Youth or League of German Girls, only going home to sleep. Parents watched their children slip away from them. Their influence waned as the Party became the true parents.

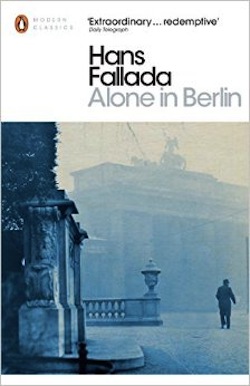

But still some brave people tried to resist in any way they could. An excellent fictional portrayal of this struggle is Hans Fallada’s novel Alone in Berlin, written by a German author just 18 months after the war. It’s based on a true story of a working class couple who write anti-Nazi messages on postcards and leave them around Berlin. In the novel, the couple were moderately supportive of Hitler until the war started, and then lost all enthusiasm once their son is killed in the invasion of France. From then on they write their postcards, and have no illusions about getting away with it. Their building, every building, is full of informers. The Nazi Party acted like a bully, and a bully always attracts a circle of sycophants. Even once they go to prison, other inmates are constantly informing on them in the hope of getting a more lenient sentence.

But still some brave people tried to resist in any way they could. An excellent fictional portrayal of this struggle is Hans Fallada’s novel Alone in Berlin, written by a German author just 18 months after the war. It’s based on a true story of a working class couple who write anti-Nazi messages on postcards and leave them around Berlin. In the novel, the couple were moderately supportive of Hitler until the war started, and then lost all enthusiasm once their son is killed in the invasion of France. From then on they write their postcards, and have no illusions about getting away with it. Their building, every building, is full of informers. The Nazi Party acted like a bully, and a bully always attracts a circle of sycophants. Even once they go to prison, other inmates are constantly informing on them in the hope of getting a more lenient sentence.

And their work goes by unheeded. Everyone is so terrified of the Gestapo that they hand in the postcards as soon as they find them, or tear them up and throw them down the toilet. The couple achieves nothing except preserving their own humanity.

It’s a brutal read, and is the most psychologically claustrophobic novel I’ve ever come across. I actually had to stop halfway through and read a totally different kind of novel (Ecstasy by Irvine Welsh) before I could finish it.

It taught me an important lesson, however, that the German people were trapped by the leader they had chosen. It’s easy to judge the Germans for not resisting the Nazis, but it seems to me that their greatest mistake wasn’t their acquiescence once Hitler was in power, but their failure to resist him before it was too late.

Images courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles, including his post-apocalyptic series Toxic World that starts with the novel Radio Hope. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

There’s a book about the Berlin underground that I keep meaning to backtrack for, and it might be useful for your research. Here’s the NYTimes review of Red Orchestra: The Story of the Berlin Underground and the Circle of Friends who Resisted Hitler. Thank you, as always, for a thought-provoking post.

One wonders how many of the people in that top photo were alive in 1946.

Sarah: Thanks for the tip, I’ll be sure to check it out.

R.K.: That depends on whether they fought on the Western or Eastern Front. In the West, many Volkssturm units eagerly surrendered to the British, Canadians, or Americans after only minimal fighting. In the East, they were more motivated due to the atrocities the Soviets were committing (in revenge for Nazi atrocities). They tended to fight hard and got slaughtered.

Once the fighting was over, the Volkssturm in the west were released usually within a matter of weeks or even days. Many Volkssturm members who fell into the hands of the Soviets ended up in gulags.

Back in 1992, the guy who made my curtains (a German immigrant to South Africa), told me how he had been pressed into service back in 1945. he was 62 when he told me the story, so he must’ve been 15 or 16.

Hermann (for it was he) told me that he was given a bazooka and stationed by a roadside to watch for enemy tanks. Presently, he heard the rumble of an approaching tank and, heart fluttering, he trained the weapon on the rise where the tank was due to appear. Soon an American tank burst into view. And then a second one. And then a third one.

Hermann flung the weapon into the bushes and ran like hell!