Fantasia 2016, Day 10, Part 2: Sharp and Short, Long and Languid (Born of Woman Showcase, Realive, and Tank 432)

The evening of Saturday, July 23, was going to be busy for me, with three shows at the De Sève Theatre. First, a showcase of short films called Born of Woman, which the Fantasia program told me would feature nine films by women directors “centred largely around themes of the body and interpersonal malaise.” Then after that two science-fiction features. The first would be Realive, about a man from our time (or close to it) who dies and is cryonically revived in 2083. The second would be Tank 432, about a squad of soldiers seeking shelter from a surreal battle within a battered tank. It looked like a promising night, and it got off to a good start in the late afternoon with the Born of Woman showcase.

The evening of Saturday, July 23, was going to be busy for me, with three shows at the De Sève Theatre. First, a showcase of short films called Born of Woman, which the Fantasia program told me would feature nine films by women directors “centred largely around themes of the body and interpersonal malaise.” Then after that two science-fiction features. The first would be Realive, about a man from our time (or close to it) who dies and is cryonically revived in 2083. The second would be Tank 432, about a squad of soldiers seeking shelter from a surreal battle within a battered tank. It looked like a promising night, and it got off to a good start in the late afternoon with the Born of Woman showcase.

The first film in the showcase was “Skin,” written, starring, and directed by Jessica Makinson. It’s an ambiguous but character-based piece, in which (if I’m reading it right) a woman (Makinson) charms a lover (Johnny Sneed), using a piece of herself. It’s beautifully shot, drenched in light, and the minimalist dialogue allows the story to be told almost entirely in visuals. Languid yet brief, the film created an almost fable-like atmosphere.

Next was “Venefica,” by Maria Wilson (director, writer, and star), following a nervous young witch as she approaches a nighttime ritual that will determine her destiny. Will she follow the path of the magic of the dark, or the magic of the light? It’s a quiet story, with long leisurely shots, in which at least one life hangs in the balance. At seven minutes, the piece is short, builds nicely, and leaves an audience with just the right amount of questions at the end. What is determined by the ritual, and what by Venefica’s own character? She has very definite ideas about which path she wants to follow, and it’s possible that the actions she’s taken to prepare the ritual show who she is as much as do the results of the ritual itself: she gets what she hopes for, but then perhaps also the hopes are a sign of what her path must be. Character, then, is destiny.

“Whole,” directed by Verena Klinger and Robert Banning, is a wonderful piece of stop-motion animation. An artisan’s trying to make a new eye for his wife, who is missing both of hers. He’s having no luck, and finally decides to sacrifice an eye of his own. The story doesn’t stop there, though. The film feels a little like a fairy tale, something out of the Grimms’ original collection, or even more like a märchen from Tieck or Hoffmann. Perfectly paced, it’s wonderful to look at, particularly the workshop filled with tools and materials and stuff to every hand; and the reactions of the puppets are masterfully animated, genuinely touching and affecting.

“Whole,” directed by Verena Klinger and Robert Banning, is a wonderful piece of stop-motion animation. An artisan’s trying to make a new eye for his wife, who is missing both of hers. He’s having no luck, and finally decides to sacrifice an eye of his own. The story doesn’t stop there, though. The film feels a little like a fairy tale, something out of the Grimms’ original collection, or even more like a märchen from Tieck or Hoffmann. Perfectly paced, it’s wonderful to look at, particularly the workshop filled with tools and materials and stuff to every hand; and the reactions of the puppets are masterfully animated, genuinely touching and affecting.

Kaitlin Tinker’s “The Man Who Caught A Mermaid” follows an old married man, Herbie (Roy Barker), a fisherman who desperately wants to catch a mermaid (Bilby Conway, I think; casting information is hard to track down for this one). And does. Or does he? It’s a seemingly simple story in which you can scent disaster approaching, and in fact we soon find things are more complex than we’d realised. An atmosphere of horror builds nicely in a dark shed lit by a single bulb where a fanged, armour-plated thing is held by Herbie. By the end apparent reality is undercut (as though Herbie’s captured Schrödinger’s mermaid). By any reading, the ending’s fittingly dark and tragic.

Anna Zlokovic wrote and directed “Shorty,” about a woman named Laura (Mary Loveless) who seems to be a kind of cosmic vampire, feeding on others to stave off non-existence. A parody of a rom-com meet-cute leads to an odd connection — will her curse complicate things? The movie’s intelligent, but at one viewing I found myself uninvolved with Laura’s situation. The visuals are often startling and wonderful, particularly Laura’s visions, and the contrast between some of the film’s more surreal images and everyday reality. But if I understand the choice Laura makes properly, it seems unconvincing — as though she chooses to become a different person for no reason, or as though a hint of interpersonal contact is enough to destroy her.

Anna Zlokovic wrote and directed “Shorty,” about a woman named Laura (Mary Loveless) who seems to be a kind of cosmic vampire, feeding on others to stave off non-existence. A parody of a rom-com meet-cute leads to an odd connection — will her curse complicate things? The movie’s intelligent, but at one viewing I found myself uninvolved with Laura’s situation. The visuals are often startling and wonderful, particularly Laura’s visions, and the contrast between some of the film’s more surreal images and everyday reality. But if I understand the choice Laura makes properly, it seems unconvincing — as though she chooses to become a different person for no reason, or as though a hint of interpersonal contact is enough to destroy her.

“The Itching,” written and directed by Dianne Bellino, uses clay animation to tell a dialogue-free story about a wolf and a group of bunnies. It’s an inversion of Mother Goose; the bunnies party in a bar with a a DJ and do coke, while the she-wolf in a dress watches anxiously and scratches her arms. The increasingly intense scratching leads to serious wounds, and it seems there’s an ocean under the wolf’s skin, filled with aquatic creatures. Will she overcome her strange affliction with the help of a sympathetic bunny? I found this was an extremely difficult film to understand. In the question-and-answer period that would follow the showcase Bellino would say it had to do with social anxiety, and that clarified things considerably — but (again, after just one viewing) I don’t see how I could have got that out of the film on its own. For me, at least, the relationship between wolves and bunnies is too well-established and too one-sidedly predatory. It’s also a relationship founded, at least to a point, in nature; whereas the idea of a wolf anxious about fitting in among bunnies isn’t. The animation’s fine, with odd colours and a surreal forest and unexpected imagery whose horror lends the clay creatures a real feeling of the macabre. But as a whole this piece didn’t work for me.

Jill Gevargizian directed “The Stylist” from her own original story, co-written by Eric Havens. It’s as glossy and visually striking as its title promises. It follows a hair stylist (Najarra Townsend) who stays late to do the hair of a demanding upwardly-mobile client (Jennifer Plas) — but this stylist has a terrible secret. It’s a clever horror movie that makes a witty play out of the distinction between a mirror and a glass ceiling. The set design is striking, high-contrast in the stylist’s salon, beautiful and warm in the glimpse we see of the stylist’s home afterward. That epilogue makes a particularly effective ending to the film; on a plot level arguably unneeded, but illuminating character and deepening what we’ve just seen.

Jill Gevargizian directed “The Stylist” from her own original story, co-written by Eric Havens. It’s as glossy and visually striking as its title promises. It follows a hair stylist (Najarra Townsend) who stays late to do the hair of a demanding upwardly-mobile client (Jennifer Plas) — but this stylist has a terrible secret. It’s a clever horror movie that makes a witty play out of the distinction between a mirror and a glass ceiling. The set design is striking, high-contrast in the stylist’s salon, beautiful and warm in the glimpse we see of the stylist’s home afterward. That epilogue makes a particularly effective ending to the film; on a plot level arguably unneeded, but illuminating character and deepening what we’ve just seen.

“Static” is an adaptation by director Tanya Lemke of a short story of the same name by Robert Shearman, who also wrote for the current iteration of Doctor Who (with the Hugo-nominated episode “Dalek”). The prose version of “Static” was in Shearman’s first short story collection, Tiny Deaths, which won the 2008 World Fantasy Award for Best Collection. It’s the tale of an older man (Eric Peterson) who desperately wants to fix his old CRT TV, with whom he has spent much of his life. It soon becomes clear that the TV — symbolically or otherwise — is a kind of objective correlative for much else that he’s lost over the years. It’s a deeply touching piece, excellently well-directed and touchingly acted by Peterson as the elderly lead. Crucially, this character isn’t sweet, or not always, and not bumbling, except on occasion. He’s a bit of both, and a bit of a lot more things, and always half-aware of the pain of many profound losses. It’s an excellent example of character-based fantasy, a perfectly executed realisation of a whimsical idea with cold steel sadness at its heart. Flashbacks are integrated perfectly into the narrative, appropriate for a story with so much to say about passing time and the human response to same.

I frankly didn’t know what sort of film could follow “Static,” but it turned out that “Disco Inferno,” by Alice Waddington, did the job perfectly. Shot in spectacular black-and-white, it struck me for much of its 12-minute runtime as a clever playing-about with The Avengers (Steed-and-Mrs-Peele version, not Captain-America-Thor-and-Iron-Man). A black-clad woman (I can’t find a full cast list online) infiltrates a richly-appointed mansion. In the mansion a strange cult seems to be enacting a bizarre occult ritual out of some Dennis Wheatley novel or Hammer horror film. The black-clad woman makes her way through satanic weirdness, intent on her mission; whimsy is flavoured by dark undertones; eventually there’s a confrontation, and we find the characters are not what we might have imagined. There’s a punch line to the whole thing that ought to be an abrupt tonal shift but that in fact works surprisingly well, having been built up through a kind of storytelling sleight-of-hand, so the resolution’s both unexpected and logical. As a whole, the movie’s a wonderful stylish piece that balances tension, horror, and comedy.

I frankly didn’t know what sort of film could follow “Static,” but it turned out that “Disco Inferno,” by Alice Waddington, did the job perfectly. Shot in spectacular black-and-white, it struck me for much of its 12-minute runtime as a clever playing-about with The Avengers (Steed-and-Mrs-Peele version, not Captain-America-Thor-and-Iron-Man). A black-clad woman (I can’t find a full cast list online) infiltrates a richly-appointed mansion. In the mansion a strange cult seems to be enacting a bizarre occult ritual out of some Dennis Wheatley novel or Hammer horror film. The black-clad woman makes her way through satanic weirdness, intent on her mission; whimsy is flavoured by dark undertones; eventually there’s a confrontation, and we find the characters are not what we might have imagined. There’s a punch line to the whole thing that ought to be an abrupt tonal shift but that in fact works surprisingly well, having been built up through a kind of storytelling sleight-of-hand, so the resolution’s both unexpected and logical. As a whole, the movie’s a wonderful stylish piece that balances tension, horror, and comedy.

A question-and-answer period followed with six of the directors: Diane Bellino (“The Itching”), Jill Gevargizian (“The Stylist”), Tanya Lemke (“Static”), Jessica Makinson (“Skin”), Kaitlin Tinker (“The Man Who Caught a Mermaid”), and Maria Wilson (“Venefica”). I took some hand-written notes. The first question, for each of the directors in turn, was: ‘why make this movie?’ Tinker said “Mermaid” came from talking abut the myth of the mermaid and modern issues of psychological projection (and noted that the woman who played the mermaid had to endure seven hours of make-up work per day). Wilson said she loves science-fiction, and with a small group of friends raised $3000 to make three movies in one location in one week. She wanted to do a story about a rite of passage, to write about freedom and choices, and to make people appreciate their own agency. Gevargizian said she had been a hair-stylist for ten years, and combined that experience with a desire to create a film from the villain’s point of view.

A question-and-answer period followed with six of the directors: Diane Bellino (“The Itching”), Jill Gevargizian (“The Stylist”), Tanya Lemke (“Static”), Jessica Makinson (“Skin”), Kaitlin Tinker (“The Man Who Caught a Mermaid”), and Maria Wilson (“Venefica”). I took some hand-written notes. The first question, for each of the directors in turn, was: ‘why make this movie?’ Tinker said “Mermaid” came from talking abut the myth of the mermaid and modern issues of psychological projection (and noted that the woman who played the mermaid had to endure seven hours of make-up work per day). Wilson said she loves science-fiction, and with a small group of friends raised $3000 to make three movies in one location in one week. She wanted to do a story about a rite of passage, to write about freedom and choices, and to make people appreciate their own agency. Gevargizian said she had been a hair-stylist for ten years, and combined that experience with a desire to create a film from the villain’s point of view.

Lemke said that she met Shearman at a Doctor Who convention and loved his story at once, finding it funny, poignant and twisted. She said that the story was not initially that personal for her, but during the filming of the story in which lung cancer features prominently, a friend and her father both died of the disease; her dog died as well. “Only romantic comedy from now on,” she promised. She had worked as a crew member before, but “Static” was her first writing and directing work; she commended the work of her lead, Eric Peterson: “Covers all sins, that acting.” Bellino said that she loved hand-made things, and liked both the visceral fairy-tale quality of her film and the way it was open to interpretation. She had wanted to make something emotional, which she did by letting her characters be vulnerable. Makinson said that part of “Skin” was true, and the rest is “playing the trope through to the end.” She was looking to depict connection in intimate ways, ways most people wouldn’t be capable of.

Asked if any personal nightmares made it into their films, most of the directors said no. Makinson said that she used to suffer from nightmares, while Bellino mentioned that the wounds in her movie were from a dream. Tinker said “I think the nightmare is that the crazy white men are in control of everything,” and spoke about how her movie had to do with the general fear of the male gaze.

Asked if any personal nightmares made it into their films, most of the directors said no. Makinson said that she used to suffer from nightmares, while Bellino mentioned that the wounds in her movie were from a dream. Tinker said “I think the nightmare is that the crazy white men are in control of everything,” and spoke about how her movie had to do with the general fear of the male gaze.

Some questions came about specific films. Bellino said that she had predator and prey be friends in her movie as part of playing with opposites, to show them coming together. Wilson said that a blue fire at the end of her film was partly produced practically, by adding fuel that made the fire burn blue, and partly done digitally. An effect in which she was lifted off the ground was done practically.

Asked whether the films represented a way for the directors to work through emotional damage, Makinson said yes, that it felt good to take an idea you’re grappling with and turn it into art; making her movie was helpful for her. Wilson said that in retrospect she thought that, making her movie after a bad break-up, she’d wanted to kill a guy. She’d also wanted to do something fantastic, and get away from reality; but the film stands as a sort of scrapbook of that moment for her. Tinker said that as naming a pet leads it to taking on attributes inherent in the name, the creation of a film is like holding up a mirror — it teaches you something about yourself. It’s rewarding as a personal process, she said, but she likes to think it’s beyond the simply personal.

Makinson added at this point (according to my notes) that watching the nine films together she’d seen a difference in the films by women, which tended to depict men as victims. Bellino said more therapeutic than making the movie was showing it to an audience and hearing their reactions. Gevargizian said “The Stylist” was the most personal film she’s made, and that she’s never felt closer to one of her films. Lemke said that you don’t think the film as a personal or therapeutic project as you make it, but that it grows after it’s finished, and you see different things within it.

On that note the question-and-answer session ended. Next came the world premiere of Realive, written and directed by Mateo Gil. In 2084, a team of doctors attempt the first successful revival of a man from cryogenic suspended animation. Their candidate is Marc Jarvis (Tom Hughes), an artist who was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumour and frozen in the 2020s. We follow Marc as he tries to negotiate and understand the new world into which he has been reborn, while also following him through his memories of his past life. Can Marc be happy in the future?

On that note the question-and-answer session ended. Next came the world premiere of Realive, written and directed by Mateo Gil. In 2084, a team of doctors attempt the first successful revival of a man from cryogenic suspended animation. Their candidate is Marc Jarvis (Tom Hughes), an artist who was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumour and frozen in the 2020s. We follow Marc as he tries to negotiate and understand the new world into which he has been reborn, while also following him through his memories of his past life. Can Marc be happy in the future?

Conceptually, this is a good question to ask, and if dramatised well, could be a compelling story. I can’t say I cared for Realive’s execution, though.

Let’s start with the future it imagines. It’s sterile, minimalist, designed in bland whites and greys. That’s fine to a point, as worldbuilding isn’t the point of the movie. But it’s difficult to imagine a believable character, or believable drama, without credible surroundings. If Marc’s supposed to be unhappy in the future, we need to understand that future to grasp his unhappiness. Lacking any sense of the future other than an offhand mention that things haven’t changed much, it’s difficult to empathise with Marc. It’s also difficult to believe that things really haven’t changed much; simply the technology that gives him life seems to put paid to that assertion.

More than that, we’re given glimpses of new social arrangements and sexual mores. The future’s polyamorous, is the implication; and yet at the same time people in this future seem oddly unemotional, if not placid. There’s a vague sense of Brave New World here, I suppose, but than also a stronger sense of some sort of 1970s-era future: the future as imagined in a time when people assumed trends of their present moment would always continue. Certainly language and mentalities don’t seem to have changed as much as one would expect, given the other changes we see.

Marc himself isn’t interested in the future, which would be fine except that this lack of interest in the exterior world helps create the sense of a deeply self-obsessed man. That in turn could be solid character-building, as it’s consistent with one of his crucial actions near the end of the film — he asks one of his few friends in the future (played by Charlotte Le Bon) to do something which would not only be important to him but also would severely affect her career and life going forward; and at no point is there any indication he thinks about the cost to her. So you might imagine that the stress of waking up in a future he doesn’t understand has left Marc emotionally and psychologically disturbed. Except … there’s no sense from any of the other characters that Marc’s acting oddly (or at least that his self-centredness is odd). The movie seems to support him in his solipsism.

Marc himself isn’t interested in the future, which would be fine except that this lack of interest in the exterior world helps create the sense of a deeply self-obsessed man. That in turn could be solid character-building, as it’s consistent with one of his crucial actions near the end of the film — he asks one of his few friends in the future (played by Charlotte Le Bon) to do something which would not only be important to him but also would severely affect her career and life going forward; and at no point is there any indication he thinks about the cost to her. So you might imagine that the stress of waking up in a future he doesn’t understand has left Marc emotionally and psychologically disturbed. Except … there’s no sense from any of the other characters that Marc’s acting oddly (or at least that his self-centredness is odd). The movie seems to support him in his solipsism.

Worse, we’re told that Marc’s an artist, but not only is his art not shown much, he as a character never seems concerned with making art. His art doesn’t seem to matter to him, either in flashbacks or in the future. There is therefore no real sense of him as an artist, meaning that the label “artist” remains merely a vague signifier of some kind of thoughtfulness or depth that the film doesn’t bring out through actual drama.

Then again, the other characters in past and future-present never come alive either. As with Marc, they all have a notable-but-uncommented-on self-absorption. The best character moment is a description by Marc of his relationship with his past-girlfriend Naomi (Oona Chaplin) delivered as a monologue over a montage of moments in their lives. It’s a good summation of their history, delivered with some wit, and in a way that reflects on themes of time and fate. Unfortunately, that moment aside, the rest of the drama in the film is dull. Marc in the future has to decide whether to accept the world in which he finds himself. Naomi in the past has to decide whether she’ll help Marc with his plan to freeze himself — which we already know she has, since we’re watching him in the future. Unfortunately, the process by which she arrives at her decision is uninteresting. Which is a general problem with the film. Character moments are uninvolving, dialogue dull, and voiceovers tedious.

Then again, the other characters in past and future-present never come alive either. As with Marc, they all have a notable-but-uncommented-on self-absorption. The best character moment is a description by Marc of his relationship with his past-girlfriend Naomi (Oona Chaplin) delivered as a monologue over a montage of moments in their lives. It’s a good summation of their history, delivered with some wit, and in a way that reflects on themes of time and fate. Unfortunately, that moment aside, the rest of the drama in the film is dull. Marc in the future has to decide whether to accept the world in which he finds himself. Naomi in the past has to decide whether she’ll help Marc with his plan to freeze himself — which we already know she has, since we’re watching him in the future. Unfortunately, the process by which she arrives at her decision is uninteresting. Which is a general problem with the film. Character moments are uninvolving, dialogue dull, and voiceovers tedious.

The flashbacks are also narratively clunky. They undercut any story momentum events in the future might have had, and tend to undercut the solidity of the future as well: Marc, our main character, seems to have more invested in the flashbacks than in his present. I’ll note also that there seemed to be a naive quality to them, Marc’s memories presented as apparently objective depictions of events; I could find no way to read events as questioning Marc’s take on things.

The flashbacks are also narratively clunky. They undercut any story momentum events in the future might have had, and tend to undercut the solidity of the future as well: Marc, our main character, seems to have more invested in the flashbacks than in his present. I’ll note also that there seemed to be a naive quality to them, Marc’s memories presented as apparently objective depictions of events; I could find no way to read events as questioning Marc’s take on things.

Are there any good elements to the movie? A few. Oddly, most of them seem to come from the science-fictional aspects in which the film seems largely uninterested. The depiction of Marc’s revival from cryonic freezing is very complete, and his slow recovery is handled credibly. Along with that, a sub-theme of medical politics and search for funding feels very real. And one of the few elements of the future we’re introduced to is a device that provides the ostensible reason for Marc’s flashbacks, a kind of memory-internet or memory-hard drive called Mind Writer, which allows people to store and share their personal memories. Having stored their memories, it also allows for the elimination of memories: “Millions of people lead completely normal lives without ever remembering anything,” we’re told with a straight face.

Still, the technology feels underdeveloped, which reflects a characteristic of the movie — there are some strong ideas, but they don’t come together. Consider some of the references the film makes: setting the thing in 2084 may recall 1984, but to no purpose I can see; while it’s charming that the scientist who re-animates Marc is named Dr. West (Barry Ward), it seems over-direct; Biblical references to Lazarus feel similarly overdetermined; and conversely references to Frankenstein are baffling as obvious thematic parallels are few and far between. So: ideas, but either treated too bluntly or too underexplored. It’s a weakness that seems echoed throughout the film. Some good character ideas, which feel underdeveloped dramatically. Some interesting ideas about the future, but not enough. If you happen to be a science-fiction fan with a deep interest in cryonics, the movie might be interesting. I can’t see it as a success otherwise.

Still, the technology feels underdeveloped, which reflects a characteristic of the movie — there are some strong ideas, but they don’t come together. Consider some of the references the film makes: setting the thing in 2084 may recall 1984, but to no purpose I can see; while it’s charming that the scientist who re-animates Marc is named Dr. West (Barry Ward), it seems over-direct; Biblical references to Lazarus feel similarly overdetermined; and conversely references to Frankenstein are baffling as obvious thematic parallels are few and far between. So: ideas, but either treated too bluntly or too underexplored. It’s a weakness that seems echoed throughout the film. Some good character ideas, which feel underdeveloped dramatically. Some interesting ideas about the future, but not enough. If you happen to be a science-fiction fan with a deep interest in cryonics, the movie might be interesting. I can’t see it as a success otherwise.

After the screening, writer/director Mateo Gil came out to take questions. An interviewer began the session by playfully asking if Gil had found Walt Disney in the course of making the movie, which Gil laughed off, mentioning in the process that his next movie would be a comedy (and that the film he’d done before Realive was a Western). He was then asked about the “DNA” Realive shared with two of Gil’s previous films, Open Your Eyes and The Sea Inside. Gil said that Realive was “the son” of those movies, and that it came from his fear of death. Gil said he liked the idea of cryonics, and that if he could live 3000 years he’d sign up at once. But he also felt it wasn’t worth it to prolong life at all costs, especially without the people and places we care for. In Marc’s situation, then, he wouldn’t re-animate. He doubted whether most people would be re-animated in the future; who would be interesting enough to be worth reviving?

Asked about the humanistic feel of the film, which avoided horror conventions, Gil said that the script was more genre-y but that they tended to take those elements out in editing, as it felt like the movie itself had rejected them. A sub-plot about an investigation into doctored recordings was largely dropped, as the film demanded that it be a romance. Asked about his decision to make the movie in English and not in Spanish, Gil said that it really wasn’t his decision — it would have been impossible to finance the movie in Spanish. That said, he had wanted to make the movie in English, as there are few countries right now where cryonics are a real issue. The movie was largely shot in English, in the Canary Islands, which in turn dictated he set the story in California as the part of the English-speaking world most closely resembling the Canaries. (He asked the audience if it was believable, and the crowd generally agreed it worked.) At the same time, due to financing issues the actors had to either be Spanish or live in Spain. Le Bon, who plays a futuristic nurse, is actually from Montreal but lives in France; the other actors were European. At the time of the screening, Gil wasn’t yet sure how people would react to the movie in Spain, admitting it was one of his fears as the film was especially personal for him.

Asked about the humanistic feel of the film, which avoided horror conventions, Gil said that the script was more genre-y but that they tended to take those elements out in editing, as it felt like the movie itself had rejected them. A sub-plot about an investigation into doctored recordings was largely dropped, as the film demanded that it be a romance. Asked about his decision to make the movie in English and not in Spanish, Gil said that it really wasn’t his decision — it would have been impossible to finance the movie in Spanish. That said, he had wanted to make the movie in English, as there are few countries right now where cryonics are a real issue. The movie was largely shot in English, in the Canary Islands, which in turn dictated he set the story in California as the part of the English-speaking world most closely resembling the Canaries. (He asked the audience if it was believable, and the crowd generally agreed it worked.) At the same time, due to financing issues the actors had to either be Spanish or live in Spain. Le Bon, who plays a futuristic nurse, is actually from Montreal but lives in France; the other actors were European. At the time of the screening, Gil wasn’t yet sure how people would react to the movie in Spain, admitting it was one of his fears as the film was especially personal for him.

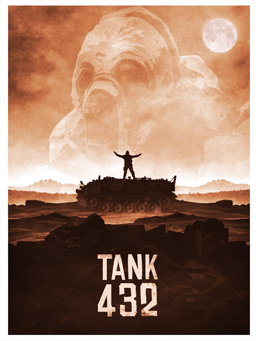

That ended the question-and-answer period. Next for me came Tank 432. This was a movie from the UK that followed a small group of British soldiers in a futuristic battlefield, trying to get back to friendly territory with two prisoners in tow. The enemy’s after them, though, and before long they end up trapped inside a tank. The tank has a hold large enough for all of them, if not large enough for them to be comfortable, but who are the people chasing them? Will they be driven out of their sanctuary? Can they get the tank moving again? Or are there darker secrets behind their mission?

Directed and written by Nick Gillespie, Tank 432 is a very well-shot movie. By that I mean not just that it does a good job of establishing geography and creating memorable images, but that it establishes atmosphere very well. The inside of the tank feels claustrophobic, the exterior war scenes are desolate with a peculiar horrific feel, glimpses of the enemy are brief and terrifying. The lighting brings out the emotional texture of the drama extremely well — to the point where the writing sometimes seems to struggle to keep up.

Directed and written by Nick Gillespie, Tank 432 is a very well-shot movie. By that I mean not just that it does a good job of establishing geography and creating memorable images, but that it establishes atmosphere very well. The inside of the tank feels claustrophobic, the exterior war scenes are desolate with a peculiar horrific feel, glimpses of the enemy are brief and terrifying. The lighting brings out the emotional texture of the drama extremely well — to the point where the writing sometimes seems to struggle to keep up.

The actual development of the drama of the film, particularly once the characters end up inside the tank, felt weirdly rudimentary to me. The characters didn’t seem like individuals, lacking specificity or distinctiveness (at the end, when it becomes more-or-less clear what we’ve been seeing, it becomes possible to imagine a reason why this is, why the edges of these personalities have been abraded — but it doesn’t retroactively improve the experience of watching their interactions play out). Their situation, both as people at war generally and also specifically as a group stuck in a small space together, does not bring out who they are. It ought to have been a fine set-up, but the underwritten personalities means that sense never really develops.

The rhythm of the film is odd as well. It runs 84 minutes, but the opening section, as the soldiers cross dangerous terrain leading up to them sheltering in the tank, feels too long. Then once inside the tank, the situation doesn’t seem to build in any connected fashion. Events happen randomly, whether attempts to get the tank moving or the discovery of something unexpected within the tank. There’s no sense of tension — desperation, yes, but not tension. I think the actors do the best they can with what they’re given to play, but the writing doesn’t give them many character moments to work with, or indeed a character-based structure that I could see.

In plot terms, I thought the logic was questionable as well. It’s difficult to write in detail about this without exploding the ending, but let’s give it a try. To start with, the opening section introduces some elements — particularly an abandoned piece of terrain that the characters investigate — that don’t pay off. More profoundly, that discovery the characters make inside the tank doesn’t seem to make sense; you wonder why it’s there for them to see. One of the characters may know more than the others, but if so you wonder why that character lets events proceed as they do. Finally, when all’s been explained (more or less), it’s similarly unclear why the forces behind events set them up the way they did.

In plot terms, I thought the logic was questionable as well. It’s difficult to write in detail about this without exploding the ending, but let’s give it a try. To start with, the opening section introduces some elements — particularly an abandoned piece of terrain that the characters investigate — that don’t pay off. More profoundly, that discovery the characters make inside the tank doesn’t seem to make sense; you wonder why it’s there for them to see. One of the characters may know more than the others, but if so you wonder why that character lets events proceed as they do. Finally, when all’s been explained (more or less), it’s similarly unclear why the forces behind events set them up the way they did.

The resolution of the film, the climax of the personal arcs of the characters, is clear enough in its general outline and cuts nicely between the different strands playing out. But the actual details, again, are questionable. A character returns without having been sufficiently established earlier in the film. And then the violent reaction one of the other characters has to him goes on too long, with insufficient motivation, and plays out more bathetically than was likely intended. I can understand the attempt to catch a sense of surrealism, but for me at least it didn’t come off and soon felt tedious. Meanwhile, some of the revelations we’ve been waiting for are underplayed, leaving much of what we’ve seen mysterious.

I’ve alluded to the fact that the ending of the film reveals a twist that explains to us what we’ve really been seeing; that’s not a surprise in and of itself, since it’s pretty clear from early on in the movie that things are very strange, more so than the characters realise. The problem is that it feels like an extended episode of The Twilight Zone, with a less sure touch in the writing. Weirdly, I suspect it might have actually played better as such — it’s not a long movie, but cutting it down to half an hour, possibly jettisoning the pre-tank parts of the film entirely, might have made it much tighter and more effective. You can almost imagine what Rod Serling would have done with a one-set story in which a handful of psychologically-deteriorating soldiers are caught up in a situation stranger than they realise, with a potentially devastating twist at the end. Serling had a sure sense of craft, and especially of structure. I don’t find that here. The result is an interesting idea that doesn’t, in the end, work.

After the film, director Nick Gillespie and producer Finn Bruce came out for a question-and-answer session. The host asked them first if the cast and crew got on each other’s nerves shooting in such a close environment as the tank, to which Gillespie said no, that in fact many of them knew each other from other films, and the whole shoot only took three weeks. Asked how they shot in the tank, Bruce said they actually used three different tanks, one with holes through which they could shoot, and one without an engine or a gearbox. Some questions from the audience asked about certain plot details, and Gillespie answered the question, elaborating a bit on what we saw. (Without wanting to give too much away, it referred to certain experiments from several decades ago, and films on YouTube of soldiers who’d been dosed with LSD.) Bruce talked about how difficult it was to get three tanks, and Gillespie spoke about collaborating with editor Tom Longmore to create some surreal dream sequences in the film.

After the film, director Nick Gillespie and producer Finn Bruce came out for a question-and-answer session. The host asked them first if the cast and crew got on each other’s nerves shooting in such a close environment as the tank, to which Gillespie said no, that in fact many of them knew each other from other films, and the whole shoot only took three weeks. Asked how they shot in the tank, Bruce said they actually used three different tanks, one with holes through which they could shoot, and one without an engine or a gearbox. Some questions from the audience asked about certain plot details, and Gillespie answered the question, elaborating a bit on what we saw. (Without wanting to give too much away, it referred to certain experiments from several decades ago, and films on YouTube of soldiers who’d been dosed with LSD.) Bruce talked about how difficult it was to get three tanks, and Gillespie spoke about collaborating with editor Tom Longmore to create some surreal dream sequences in the film.

That wrapped up the night for me, and a long day of films. I’d seen genre works of varying lengths (and, with the VR films from earlier in the day, varying media). Some had worked, some had not. I thought that Realive and Tank 432 hadn’t balanced character with plot effectively — the former aspiring to build a character, but not finding a credible dramatic structure based on its science-fictional ideas, the latter not creating characters strong enough to carry its story. But most of the short films I’d seen before that had told their stories much more successfully. The luck of the draw, perhaps, but at least it was interesting to see so many different approaches to genre one after another. I’d have an equally mixed bag coming up the next day; but it would work out a fair bit better.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.