Much of a Muchness: Phyllis Eisenstein’s Born to Exile

Recently I was reading an editorial in Fantasy Fiction, an old magazine from near the end of the pulp era. This is the kind of thing I’m apt to do, especially when I should be getting some work done, but in this case I was hooked by the title, which was one of Latin’s greatest hits about reading: NON MULTA, SED MULTUM (“not many things, but much of a thing”).

The message of the editorial was that the editor was seeing too many stories that overdid the number of fantastic elements: “Recently a story came in which had everything — ghosts were making a compact with a group of trolls to defeat the Greek gods, now about to retake the world with a bunch of Hebraic letter incantations.”

The editor felt this was bad and stopped reading on the third page. I say it sounds awesome and the editor should have been banished to the outer darkness where there shall be wailing and gnashing of teeth. But I’m of the opposite school of fantasy — the “more cowbell” school, you might call it (to allude to another classic). Some people will try to tell you that less is more, but “more cowbell” people insist that only more is more: more miracles, more fireballs, more talking squids in space.

The truth is that neither school is right or wrong; it’s just a question of what works in a given story. The advantage of the non multa, sed multum approach is that it allows the writer to explore the ramifications of a fantastic concept, and maybe work in a character or two, not to mention a more carefully detailed world.

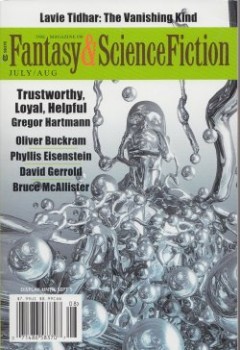

A classic of this less-is-more approach is Phyllis Eisenstein’s long-running series about Alaric, the wandering minstrel with a talent for teleportation. How long-running? The first story in the series appeared in F&SF back in August 1971. The most recent (but hopefully not the last) Alaric story appeared in the same magazine last month (August 2016).

With the indulgence of John O’Neill, Black Gate’s intrepid and Alfie-award-winning editor, I’m going to cover the series in three installments: one on the first batch of stories, collected as-if-it-were-a-novel in Born to Exile (Arkham, 1978); another on the second set of stories, collected as In the Red Lord’s Reach; and a last one on the more recent uncollected stories.

Eisenstein may not be a name to conjure with these days. God knows what name is anymore: I was just reading something online which suggested that Ursula Le Guin and Robert Silverberg were among the “Most Underrated Sci-fi Authors.” If this is true, we’re all doomed.

But this much is certain: Eisenstein’s work is something to conjure with. She is a powerful, understated stylist, giving a scene just enough detail to summon images into the reader’s mind; her stories are rich in imagination, emotion, and ideas; they always land with an impact the reader feels.

That’s the TL; DR version. For more details, read on.

Born to Exile first appeared as a series of stories in the pages of F&SF in the early-to-mid 70s. So is it a collection of stories or a novel? ISFDb and the book’s publishers insist that it’s a novel. But the book won a Balrog Award — yes, a coveted Balrog Award — as “Best Collection.”

In truth it’s something in-between: a series of stories linked by an over-arching narrative. I call this an episodic novel; a more widespread term — which I hate — is “fix-up” (apparently coined by A.E. Van Vogt, who fixed up a lot of them). They’re not unique to sf/f: I know of examples by P.G. Wodehouse, Agatha Christie, and Dashiell Hammett, at least, and more knowledgeable people could probably cite more examples. But these books were once extremely common, as writers (or their executors) took to repackaging in paperbacks batches of work that had appeared serially in magazines.

This type of book is not so common anymore, and when they do appear some people are not so crazy about them. But, when well done, they provide a narrative satisfaction which is different from novels or story collections. They have something of a novel’s depth or breadth of detail, along with the swifter, more pointed narrative pace of short stories.

Although we’re not talking about epic fantasy here, Born to Exile begins like a good epic, in medias res: Alaric the minstrel arrives at the court of a king he had long intended to visit, although he’s never been there before. Swiftly and capably Eisenstein inks in the background — Alaric’s mysterious origin, discovered as a baby in the wilderness held in the gory grip of a severed hand; his talent for teleportation; his homeless wanderings and training as a minstrel in a medieval landscape, not quite that of earth — between vivid scenes set in Alaric’s present at Castle Royale.

Alaric’s musical skills and personal charm get him into a romantic entanglement his teleportation can’t really yank him out of. But he’s saved, in the end, by a lie, an acrobatic trick, and the loyalty of people who’ve grown fond of him. The king banishes him from the realm and he departs, as he arrived, a homeless exile. This is Alaric’s paradox: his talent can take him anywhere — except where he wants to be.

Future episodes take him to a sinister inn surrounded by trackless woods, a superstitious village that keeps a one-handed witch in a well, and the capital of a piratical empire ruled by an inbred aristocracy of teleporting thieves.

Everywhere Alaric goes, he meets people who believe in sorcery and witchcraft, and many take him for a magician. But Alaric the wonderworker is a rationalist and does not believe in magic. There is no evidence of it anywhere in Alaric’s world, except the ability to teleport. Arguably, despite their medieval settings, these stories are examples of sociological science fiction, more akin to Larry Niven’s teleportation series from the same period than, say, Andre Norton’s Witch World novels.

That’s not to say that the stories are dry thought-experiments. Each is an adventure in which the hero (and the reader) learns more about his world and himself. But each episode is also a portrait of a society molded by fear of magic, and the reality of power — from the first story, where the surly charlatan Medron keeps the king under his thumb by fostering his irrational fear of magic, to the last, where the “lords of all power” use the superstition of the many as a cloak for the power of the few.

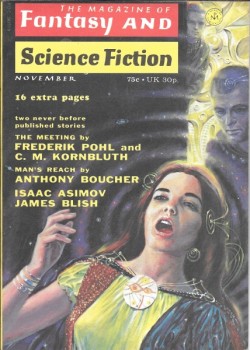

Readers of Black Gate are likely to have a bookish interest in the publication history of a given book, so I guess I’ll expand on that a little here. The book originally appeared in four installments in F&SF over three-and-a-half years. None of those stories received a cover illustration, but the third and fourth stories were the lead stories in their respective issues.

Some of those issues were pretty big deals at the time, too: Alaric’s first appearance was in the same issue as the conclusion of Roger Zelazny’s brilliant antiheroic fantasy, Jack of Shadows. His second outing (November 1972) was in the same issue as “The Meeting,” the Hugo-Award-winning story by Pohl and Kornbluth. That must have put Eisenstein on people’s radar; I know that’s how it worked for me.

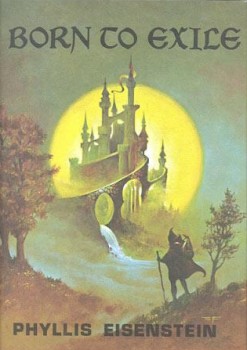

Three years after the fourth story appeared in F&SF, Arkham House published a collected edition/(episodic) novel/fix-up — whatever you want to call it. It was graced by a cover painting and interior illustrations by Stephen Fabian, one of the great fantasy artists of that age or any age.

Your mileage may vary, but I think this was one of the best things Fabian has done. Some fantasy paintings shut down the mind and the imagination — like a badly done photograph, a mugshot of a Muse. Fabian’s painting opens a door and lets you see a vista of Eisenstein’s world. There’s a story about how that lute-carrying figure came upon that castle — a story about what happened there — a story about what lies beyond. The painting expresses this without showing it.

I’m not as crazy about the cover paintings of the paperback editions (especially the inexplicably green-and-pink thing from Dell), but at least there were paperback editions. The last one, from Roc, is more than 20 years old now. Copies of all the editions can be found online, but maybe it’s time for a new edition — an e-book, maybe.

In his note on “The Lords of All Power,” the late and unquestionably great Ed Ferman described the story as the conclusion of the series. Fortunately, it was only the conclusion of the first Alaric series. Eisenstein and her minstrel would teleport back into F&SF’s pages, but it would take a few years. More on that another time.

James Enge is the author of the World-Fantasy-nominated novel Blood of Ambrose, featuring Morlock Ambrosius, a character who debuted in the pages of Black Gate. His latest novel is The Wide World’s End (Pyr, 2015). Keep an eye on him at his website, jamesenge.com, or via Facebook.

I don’t know, fantasy book covers with musicians are always pitchy. It’s off the list if there is a lute involved or a feathered cap. Disney style castles can really throw it. And I have a rule – it’s not even a rule it’s more like a built in instinct, that I never read anything where any character on the cover is wearing a pointy hat. Conversely Fabian’s is the best cover. But that hat – is that Wendi the Good Witch from Casper ? That’s probably my base response to all pointy hats. Then there is the Dell cover and the buccaneer boots. Never. Oh God no never

Your write-up reminds me I’ve been meaning to read these since first meeting Alaric in “The Caravan to Nowhere” in F&SF a few years ago. As to the cover art, would Fabian find a place on today’s books?

Wonderful to see you back at BG.

I do like a good tragic paradox. I’ll have to take a look.

None of those covers would have won me over, except possibly the Fabian. And then the jacket copy would have had to promise that the lute would not be too corny. None of the stuff calibrated to sell this book is nearly as persuasive as your description of what makes it cool.

A helpful reminder that even before the days of the photoshopped guy in the hood, terrible covers still existed.