The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: The Master Plot Formula (per Lester Dent)

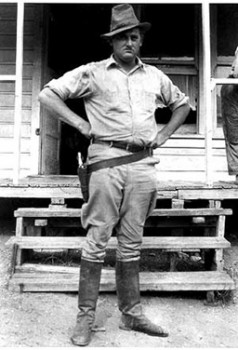

Lester Dent was a prolific pulp author, best remembered for creating the adventure hero, Doc Savage.

Lester Dent was a prolific pulp author, best remembered for creating the adventure hero, Doc Savage.

And speaking of Doc Savage, there is currently a Shane Black film project to star Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson as The Man of Bronze. Hopefully it will introduce Savage and Dent to a new generation.

The Doc Savage stories were published under the house name of Kenneth Robeson, which is a reason Dent’s name isn’t as well-remembered as it should be.

Dent cranked out 159 Doc Savage novels, but he also wrote hundreds of short stories for the pulps across several genres, including war, westerns and mysteries. The John D. MacDonald fan (which should be everyone!) might want to check out his two Oscar Sail stories for a little hint of Travis McGee. “Sail” is included in the massive (over a thousand pages!) anthology from Otto Penzler, The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories.

Will Murray (whose name you’re going to be seeing again here at Black Mask very soon) compiled a thorough bibliography, and it includes a very nice intro about Dent.

Dent, who died in 1959, a few weeks after suffering a heart attack, left behind a master plot formula for generating 6,000 word short stories. I’m going to let you read it below, in full, then give you some comments related to it from one of the top fantasy authors of all time.

This is a formula, a master plot, for any 6000 word pulp story. It has worked on adventure, detective, western and war-air. It tells exactly where to put everything. It shows definitely just what must happen in each successive thousand words. No yarn of mine written to the formula has yet failed to sell. The business of building stories seems not much different from the business of building anything else.

Here’s how it starts:

1. A DIFFERENT MURDER METHOD FOR VILLAIN TO USE

2. A DIFFERENT THING FOR VILLAIN TO BE SEEKING

3. A DIFFERENT LOCALE

4. A MENACE WHICH IS TO HANG LIKE A CLOUD OVER HEROOne of these DIFFERENT things would be nice, two better, three swell. It may help if they are fully in mind before tackling the rest.

A different murder method could be — different. Thinking of shooting, knifing, hydrocyanic, garroting, poison needles, scorpions, a few others, and writing them on paper gets them where they may suggest something. Scorpions and their poison bite? Maybe mosquitoes or flies treated with deadly germs?

If the victims are killed by ordinary methods, but found under strange and identical circumstances each time, it might serve, the reader of course not knowing until the end, that the method of murder is ordinary.

Scribes who have their villain’s victims found with butterflies, spiders or bats stamped on them could conceivably be flirting with this gag.

Probably it won’t do a lot of good to be too odd, fanciful or grotesque with murder methods.

The different thing for the villain to be after might be something other than jewels, the stolen bank loot, the pearls, or some other old ones.

Here, again one might get too bizarre.

Unique locale? Easy. Selecting one that fits in with the murder method and the treasure–thing that villain wants–makes it simpler, and it’s also nice to use a familiar one, a place where you’ve lived or worked. So many pulpateers don’t. It sometimes saves embarrassment to know nearly as much about the locale as the editor, or enough to fool him.

Here’s a nifty much used in faking local color. For a story laid in Egypt, say, author finds a book titled “Conversational Egyptian Easily Learned,” or something like that. He wants a character to ask in Egyptian, “What’s the matter?” He looks in the book and finds, “El khabar, eyh?” To keep the reader from getting dizzy, it’s perhaps wise to make it clear in some fashion, just what that means. Occasionally the text will tell this, or someone can repeat it in English. But it’s a doubtful move to stop and tell the reader in so many words the English translation.

The writer learns they have palm trees in Egypt. He looks in the book, finds the Egyptian for palm trees, and uses that. This kids editors and readers into thinking he knows something about Egypt.

Here’s the second installment of the master plot.

Divide the 6000 word yarn into four 1500 word parts. In each 1500 word part, put the following:

FIRST 1500 WORDS

1–First line, or as near thereto as possible, introduce the hero and swat him with a fistful of trouble. Hint at a mystery, a menace or a problem to be solved–something the hero has to cope with.

2–The hero pitches in to cope with his fistful of trouble. (He tries to fathom the mystery, defeat the menace, or solve the problem.)

3–Introduce ALL the other characters as soon as possible. Bring them on in action.

4–Hero’s endevours land him in an actual physical conflict near the end of the first 1500 words.

5–Near the end of first 1500 words, there is a complete surprise twist in the plot development.SO FAR:

Does it have SUSPENSE?

Is there a MENACE to the hero?

Does everything happen logically?At this point, it might help to recall that action should do something besides advance the hero over the scenery. Suppose the hero has learned the dastards of villains have seized somebody named Eloise, who can explain the secret of what is behind all these sinister events. The hero corners villains, they fight, and villains get away. Not so hot.

Hero should accomplish something with his tearing around, if only to rescue Eloise, and surprise! Eloise is a ring-tailed monkey. The hero counts the rings on Eloise’s tail, if nothing better comes to mind.

They’re not real. The rings are painted there. Why?

SECOND 1500 WORDS

1–Shovel more grief onto the hero.

2–Hero, being heroic, struggles, and his struggles lead up to:

3–Another physical conflict.

4–A surprising plot twist to end the 1500 words.NOW: Does second part have SUSPENSE?

Does the MENACE grow like a black cloud?

Is the hero getting it in the neck?

Is the second part logical?DON’T TELL ABOUT IT***Show how the thing looked. This is one of the secrets of writing; never tell the reader–show him. (He trembles, roving eyes, slackened jaw, and such.) MAKE THE READER SEE HIM.

When writing, it helps to get at least one minor surprise to the printed page. It is reasonable to to expect these minor surprises to sort of inveigle the reader into keeping on. They need not be such profound efforts. One method of accomplishing one now and then is to be gently misleading. Hero is examining the murder room. The door behind him begins slowly to open. He does not see it. He conducts his examination blissfully. Door eases open, wider and wider, until–surprise! The glass pane falls out of the big window across the room. It must have fallen slowly, and air blowing into the room caused the door to open. Then what the heck made the pane fall so slowly? More mystery.

Characterizing a story actor consists of giving him some things which make him stick in the reader’s mind. TAG HIM.

BUILD YOUR PLOTS SO THAT ACTION CAN BE CONTINUOUS.

THIRD 1500 WORDS

1–Shovel the grief onto the hero.

2–Hero makes some headway, and corners the villain or somebody in:

3–A physical conflict.

4–A surprising plot twist, in which the hero preferably gets it in the neck bad, to end the 1500 words.DOES: It still have SUSPENSE? The MENACE getting blacker?

The hero finds himself in a hell of a fix?

It all happens logically?These outlines or master formulas are only something to make you certain of inserting some physical conflict, and some genuine plot twists, with a little suspense and menace thrown in. Without them, there is no pulp story.

These physical conflicts in each part might be DIFFERENT, too. If one fight is with fists, that can take care of the pugilism until next the next yarn. Same for poison gas and swords. There may, naturally, be exceptions. A hero with a peculiar punch, or a quick draw, might use it more than once.

The idea is to avoid monotony.

ACTION: Vivid, swift, no words wasted. Create suspense, make the reader see and feel the action.

ATMOSPHERE: Hear, smell, see, feel and taste.

DESCRIPTION: Trees, wind, scenery and water.

THE SECRET OF ALL WRITING IS TO MAKE EVERY WORD COUNT.

FOURTH 1500 WORDS

1–Shovel the difficulties more thickly upon the hero.

2–Get the hero almost buried in his troubles. (Figuratively, the villain has him prisoner and has him framed for a murder rap; the girl is presumably dead, everything is lost, and the DIFFERENT murder method is about to dispose of the suffering protagonist.)

3–The hero extricates himself using HIS OWN SKILL, training or brawn.

4–The mysteries remaining–one big one held over to this point will help grip interest–are cleared up in course of final conflict as hero takes the situation in hand.

5–Final twist, a big surprise, (This can be the villain turning out to be the unexpected person, having the “Treasure” be a dud, etc.)

6–The snapper, the punch line to end it.HAS: The SUSPENSE held out to the last line?

The MENACE held out to the last?

Everything been explained?

It all happen logically?

Is the Punch Line enough to leave the reader with that WARM FEELING?

Did God kill the villain?

Or the hero?

In 1992, fantasy author extraordinaire Michael Moorcock published a collection of interviews with Colin Greenland, titled Michael Moorcock, Death is No Obstacle. Moorcock took Dent’s 6,000 word formula and adapted it for writing a 60,000 word novel in three days. Apparently he used this formula frequently in his early days. Here are several excerpts from Moorcock’s approach.

“If you’re going to do a piece of work in three days, you have to have everything properly prepared.”

“[The formula is] The Maltese Falcon. Or the Holy Grail. You use the quest theme, basically. In The Maltese Falcon it’s a lot of people after the same thing, which is the Black Bird. In Mort D’Arthur it’s also a lot of people after the same thing, which is the Holy Grail. That’s the formula for Westerns too: everybody’s after the gold of El Dorado or whatever.”

“The formula depends on that sense of a human being up against superhuman forces, whether it’s Big Business, or politics, or supernatural Evil, or whatever. The hero is fallible in their terms, and doesn’t really want to be mixed up with them. He’s always just about to walk out when something else comes along that involves him on a personal level.” (An example of this is when Elric’s wife gets kidnapped.)

“There is an event every four pages, for example — and notes. Lists of things you’re going to use. Lists of coherent images; coherent to you or generically coherent. You think: ‘Right, Stormbringer: swords; shields; horns”, and so on.”

“(I prepared) A complete structure. Not a plot, exactly, but a structure where the demands were clear. I knew what narrative problems I had to solve at every point. I then wrote them at white heat; and a lot of it was inspiration: the image I needed would come immediately [when] I needed it. Really, it’s just looking around the room, looking at ordinary objects and turning them into what you need. A mirror: a mirror that absorbs the souls of the damned.”

“I was also planting mysteries that I hadn’t explained to myself. The point is, you put in the mystery, it doesn’t matter what it is. It may not be the great truth that you’re going to reveal at the end of the book. You just think, I’ll put this in here because I might need it later.”

“What I do is divide my total 60,000 words into four sections, 15,000 words apiece, say; then divide each into six chapters. … In section one the hero will say, “There’s no way I can save the world in six days unless I start by getting the first object of power”. That gives you an immediate goal, and an immediate time element, as well as an overriding time element. With each section divided into six chapters, each chapter must then contain something which will move the action forward and contribute to that immediate goal.

“Very often it’s something like: attack of the bandits — defeat of the bandits — nothing particularly complex, but it’s another way you can achieve recognition: by making the structure of a chapter a miniature of the overall structure of the book, so everything feels coherent. The more you’re dealing with incoherence, with chaos, the more you need to underpin everything with simple logic and basic forms that will keep everything tight. Otherwise the thing just starts to spread out into muddle and abstraction.

“So you don’t have any encounter without information coming out of it. In the simplest form, Elric has a fight and kills somebody, but as they die they tell him who kidnapped his wife. Again, it’s a question of economy. Everything has to have a narrative function.”

“There’s always a sidekick to make the responses the hero isn’t allowed to make: to get frightened; to add a lighter note; to offset the hero’s morbid speeches, and so on. … The hero has to supply the narrative dynamic, and therefore can’t have any common-sense. Any one of us in those circumstances would say, ‘What? Dragons? Demons? You’ve got to be joking!’ The hero has to be driven, and when people are driven, common sense disappears. You don’t want your reader to make common sense objections, you want them to go with the drive; but you’ve got to have somebody around who’ll act as a sort of chorus.”

“‘When in doubt, descend into a minor character.’ So when you’ve reached an impasse, and you can’t move the action any further with your major character, switch to a minor character ‘s viewpoint which will allow you to keep the narrative moving and give you time to think.”

I feel I should put something of my own in quotes in this post for some reason… I’m going to look at various elements of Dent and Moorcock’s points in a future post, but you can see similarities and interesting points in their words above.

I half-heartedly tried to write a Sherlock Holmes story with Dent’s formula, but gave up pretty quickly. However, as I studied Dent’s formula, it seemed to me that it would work very well for a Conan tale. Which got me to thinking that maybe it could also be used for a new Steve Harrison story. You know: Steve Harrison. I’m fairly certain I’m going to try some type of short story with Dent’s formula.

I’d like to read all of Moorcock’s thoughts, but the book is ridiculously expensive to buy. You’d think it would be perfect for an e book reissue. Anybody reading this who has access to Moorcock should suggest that.

I haven’t written about Dent before here at Black Gate, but I have touched on Moorcock a few times:

Elric & “The Jade Man’s Eyes”

Elric at 221B Baker Street

You can read Bob Byrne’s ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column here at Black Gate every Monday morning.

He founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He is an ongoing contributor to The MX Book of New Sherlock Stories series of anthologies, with stories in Volumes III, IV and the upcoming V.

Every four or five years or so, I get a hankering to relive the days of my youth and I pull a Doc Savage off the shelf. The experience is always the same – about 20 or 30 pages in, I shake my head as the realization dawns on me – these things are NOTHING BUT PLOT. There’s literally NOTHING in them but that. What’s amazing is that I always manage to forget that!

I went through a Doc Savage phase a couple decades ago and read the first dozen books. I liked them. But I haven’t gone back, though I’d like to read a few dozen more if I had the time.

But I do recognize the Doc stories as the blueprints for Clive Cussler’s Dirk Pitt and Kurt Austin stories which I used to (Pitt) and still do (Austin) thoroughly enjoy.

And I’ve read several of Dent’s short stories, which I like.

[…] Internet Notes are related to planning – – I stumbled across a spreadsheet tool to help with creating outlines for novels. I’ve not tried it yet, but it looks like it might be fairly easy to use – http://www.fantasyscroll.com/master-outlining-and-tracking-tool-for-novels/ – Black Gate had an article about The Master Plot Formula, a guide to writing a 6000 word pulp story, as written by Lester Dent. Dent was a prolific writer in the dime novel days. He created Doc Savage and wrote 159 novels featuring the character in only 16 years, while also contributing countless short stories to other magazines. His formula is recommended to aspiring authors. – https://www.blackgate.com/2016/09/05/the-public-life-of-sherlock-holmes-the-master-plot-formula-per-… […]