Blogging Marvel’s Master of Kung-Fu, Part Three

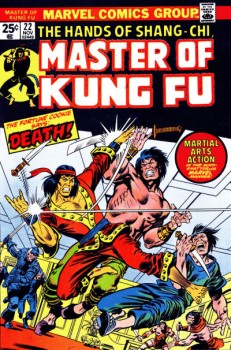

Master of Kung Fu #22 sees the welcome return of artist Paul Gulacy who came and went a bit in these early issues. The first half of the story sees Shang-Chi set upon by Si-Fan assassins at a Chinese restaurant in New York before infiltrating his father’s skyscraper base of operations. Fu Manchu has captured both Sir Denis Nayland Smith and Black Jack Tarr. Shang-Chi stows away aboard Fu Manchu’s private jet unaware of their destination. Once on the ground, he follows as his father’s minions lead their captives to a cave in the side of a mountain which has been filled with dynamite. Shang-Chi rescues the two Englishmen and prevents the detonation which would have seen Fu Manchu kill his archenemy in the same instant he destroyed Mount Rushmore. Doug Moench, like Steve Englehart before him, has an embarrassment of riches that are largely squandered with insufficient page count to fully develop his narrative. This would soon change, however, and make the series one of the finest published in the 1970s.

Master of Kung Fu #22 sees the welcome return of artist Paul Gulacy who came and went a bit in these early issues. The first half of the story sees Shang-Chi set upon by Si-Fan assassins at a Chinese restaurant in New York before infiltrating his father’s skyscraper base of operations. Fu Manchu has captured both Sir Denis Nayland Smith and Black Jack Tarr. Shang-Chi stows away aboard Fu Manchu’s private jet unaware of their destination. Once on the ground, he follows as his father’s minions lead their captives to a cave in the side of a mountain which has been filled with dynamite. Shang-Chi rescues the two Englishmen and prevents the detonation which would have seen Fu Manchu kill his archenemy in the same instant he destroyed Mount Rushmore. Doug Moench, like Steve Englehart before him, has an embarrassment of riches that are largely squandered with insufficient page count to fully develop his narrative. This would soon change, however, and make the series one of the finest published in the 1970s.

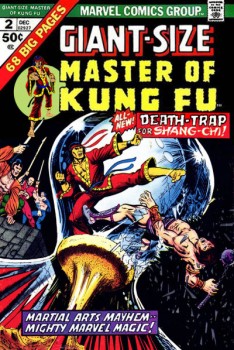

Most of Marvel’s Giant-Size quarterly titles were throwaways, much like too many of their special Annual editions, but Giant-Size Master of Kung Fu #2 was a 40-page epic designed to showcase both the character of Shang-Chi and the talents of the series’ writer and artist, respectively. Doug Moench had been harboring a desire to address racism and bigotry directly and a series with an Asian protagonist gave him the perfect forum to do so. Paul Gulacy now had the freedom to display martial arts fighting as well as moving displays of romance and longing relying solely on the power of his images in a string of panels that conveyed storytelling free of words. Even more significant is the fact that Gulacy’s depictions of lust and attraction never pandered to titillation as the artist evinced a mature understanding of the art form’s possibility. The fact that he was strongly influenced by cinema and Steranko’s pop art work of the 1960s take nothing away from the fact that Gulacy was coming into his own as an artist with this title.

The story itself sees Shang-Chi meeting Sandy, a young Asian-American woman who runs a martial arts studio in Manhattan. Their romance is brief, but their meeting is not coincidental as it first seems. Sir Denis Nayland Smith dispatches Shang-Chi on a mission to Peking to safeguard a Chinese scientist whose work has attracted Fu Manchu’s attention. The Si-Fan and British Intelligence are both willing to risk running afoul of the Communist government to get their respective hands on Dr. Ling and his secret invention. Shang-Chi endures a harrowing flight to Peking which has been infiltrated by Si-Fan assassins. His arrival in Peking culminates with an incredibly violent street fight where he overcomes seemingly impossible odds and vanquishes a crowd of both assassins and gang members who have gathered to stop him in his mission. Sandy turns up in Peking and unexpectedly reveals she is also an agent of Sir Denis as well as Dr. Ling’s daughter.

Shang-Chi’s feelings for the girl cloud his judgement and, in short order, Sandy is abducted by the Si-Fan while her father commits suicide to prevent his invention from falling into the Si-Fan’s hands. Shang-Chi is overcome just seconds after finding Dr. Ling’s lifeless body. Drugged by Fu Manchu, Shang-Chi is put through a complex series of tortures designed to weaken him until the point where he reveals the nature of Dr. Ling’s invention which proves not to be a weapon of mass destruction at all. Smith and Black Jack Tarr lead a concentrated assault on Fu Manchu’s castle. The Devil Doctor escapes, of course, but as Shang-Chi recovers from the effects of the drug, he realizes he himself killed Sandy during one of the psychedelic tortures inflicted by his father. As good as the story is, the reader is still left wishing it had been spread over several issues to take full advantage of the story’s scope. Happily, increased sales would mean editor Roy Thomas would soon approve just that and allow the title to finally blossom.

As an interesting aside, these early issues promised many things that never came to be including a black & white companion magazine for Fu Manchu set in the 1930s and a Shang-Chi meets the Yellow Claw storyline originally set for the third issue of the quarterly title. Paul Gulacy temporarily left the series with his inker, Al Milgrom stepping up to replace him. Milgrom was even announced in the letters page as the new artist for the title, but after only two issues, Gulacy returned and no more was said publicly about his departure. The letters page also contained a highly truncated letter of grievances recounted by an incensed Gene Christie regarding the series’ infidelity to Sax Rohmer’s characters. Christie today is one of the leading Rohmer authorities who has edited several anthologies of the author’s work. While Marvel went to pains to publicly respond to what they insisted was a “surprisingly small number” of angry “Rohmerites,” it should be noted the call to action campaign originated in the pages of The Rohmer Review fanzine with Dr. Robert E. Briney (previously an unpaid consultant for Marvel when they launched the series) leading the charge after both Rohmer’s widow, Elizabeth and the author’s former assistant (and eventual heir), Cay Van Ash expressed their displeasure with Marvel’s handling of the material. Seen from the vantage of over forty years later, Marvel did an excellent job in crafting a comic book sequel series and were certainly more faithful to Rohmer than nearly any of the film or television adaptations. While continuation authors are only a footnote to the original at best, the current author at least would never have attempted to carry on without the influence of the handful of issues of the series that he read as a child growing up in the 1970s.

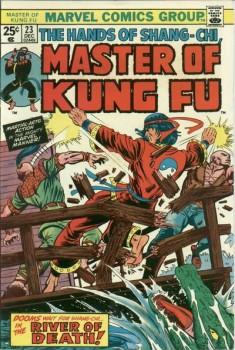

Meantime, Doug Moench undertook a three-part South American epic starting in issue #23. Al Milgrom’s art is impressive, but he never seems fully comfortable depicting the series’ hero. Sir Denis sends Black Jack Tarr to retrieve Shang-Chi for a mission to South America to seek out Nazi war criminal, Wilhelm Bucher. The disfigured former Gestapo chief has been assembling a nuclear warhead at his jungle retreat and has attracted the attention of both the Si-Fan and British Intelligence. Moench does an excellent job contrasting the character of Black Jack Tarr whose experiences during the Second World War have left him with a resentment of Asians he struggles to overcome with the outright racism of their contact in South America, the Aryan adventurer, Richard Strawn (an obvious allusion to James Clavell’s Dirk Struan, the imperialist patriarch of the author’s six-book “Asian Saga”). The look and feel of the story would have made it more suited to the more adult companion magazine, Deadly Hands of Kung Fu. I do suspect it may have originally been intended for publication there. The climactic revelation that Strawn is really Bucher in disguise is fully expected, but the exotic locale, crocodile fight, the race against time, and the overt grappling with racial hatred from Nazism to commonplace bigotry make this issue a standout.

Meantime, Doug Moench undertook a three-part South American epic starting in issue #23. Al Milgrom’s art is impressive, but he never seems fully comfortable depicting the series’ hero. Sir Denis sends Black Jack Tarr to retrieve Shang-Chi for a mission to South America to seek out Nazi war criminal, Wilhelm Bucher. The disfigured former Gestapo chief has been assembling a nuclear warhead at his jungle retreat and has attracted the attention of both the Si-Fan and British Intelligence. Moench does an excellent job contrasting the character of Black Jack Tarr whose experiences during the Second World War have left him with a resentment of Asians he struggles to overcome with the outright racism of their contact in South America, the Aryan adventurer, Richard Strawn (an obvious allusion to James Clavell’s Dirk Struan, the imperialist patriarch of the author’s six-book “Asian Saga”). The look and feel of the story would have made it more suited to the more adult companion magazine, Deadly Hands of Kung Fu. I do suspect it may have originally been intended for publication there. The climactic revelation that Strawn is really Bucher in disguise is fully expected, but the exotic locale, crocodile fight, the race against time, and the overt grappling with racial hatred from Nazism to commonplace bigotry make this issue a standout.

The middle portion of the South American adventure is the let down, at least artistically. While Al Milgrom appears to have done the majority of the uniformly excellent work, his rendering of the hero have been subjected to a number of different hands (Jim Starlin, Alan Weiss, and Walt Simonson among them). The result is Shang-Chi sometimes closely resembles Buscema’s Conan in both appearance and physique. This is unfortunate and distracts from the quality of both Milgrom’s backgrounds and supporting characters as well as Moench’s script which sees a surprising amount of violence even for this title (further convincing me the story was intended for the Code-free magazine) as we watch Bucher receive his comeuppance. Shang-Chi sustains his first serious injury in the course of the series and Fu Manchu pales as a villain, despite his prodigious intelligence, compared to the hate-filled Nazi war criminal and his legion of fanatical Fourth Reich followers at the jungle camp.

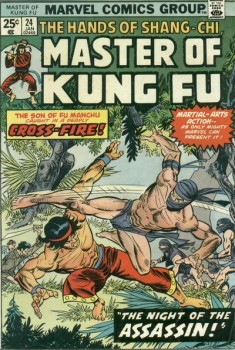

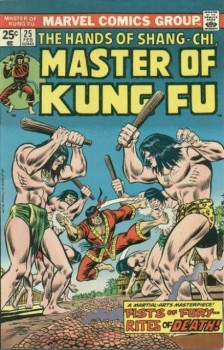

Issue #25 sees the welcome return of Paul Gulacy as artist in what is otherwise a filler story, though a pleasant wrap-up to the South American sojourn. Sir Denis, Black Jack, and Shang-Chi are making their way through the jungle back to their private plane when Shang-Chi is distracted by a faint sound. Wandering off, he discovers a native child about to be savaged by a jaguar. Gulacy’s graceful depiction of action scenes make all the difference and the reader finds themselves granting this rather slight story a warmer welcome than it might otherwise receive. The balance of the issue concerns Shang-Chi’s attempts to return the infant safely back to his mother, but he must face the superstitions of her tribe and an opportunistic attempt at a coup from a rival who views both Shang-Chi and the child as pawns to manipulate. Doug Moench makes more of a story where the protagonist and the rest of the cast have no common tongue with which to communicate by making it a demonstration (cleverly told twice) of the fable of the frog and the scorpion. In the final scene, Shang-Chi reaches the beach where Sir Denis and Black Jack Tarr await him oblivious of his detour and his lesson in character vs. logic.

Issue #25 sees the welcome return of Paul Gulacy as artist in what is otherwise a filler story, though a pleasant wrap-up to the South American sojourn. Sir Denis, Black Jack, and Shang-Chi are making their way through the jungle back to their private plane when Shang-Chi is distracted by a faint sound. Wandering off, he discovers a native child about to be savaged by a jaguar. Gulacy’s graceful depiction of action scenes make all the difference and the reader finds themselves granting this rather slight story a warmer welcome than it might otherwise receive. The balance of the issue concerns Shang-Chi’s attempts to return the infant safely back to his mother, but he must face the superstitions of her tribe and an opportunistic attempt at a coup from a rival who views both Shang-Chi and the child as pawns to manipulate. Doug Moench makes more of a story where the protagonist and the rest of the cast have no common tongue with which to communicate by making it a demonstration (cleverly told twice) of the fable of the frog and the scorpion. In the final scene, Shang-Chi reaches the beach where Sir Denis and Black Jack Tarr await him oblivious of his detour and his lesson in character vs. logic.

William Patrick Maynard is the authorized continuation writer for the Estate of Sax Rohmer. His third Fu Manchu thriller, The Triumph of Fu Manchu will be published by Black Coat Press later this year.

In the 70s this was a jewel in Marvel’s crown especially when Gulacy was going thru his ‘Hollywood’ period. Gene Day was a terrific replacement and we lost a treasure with his early passing. The series was consistent in quality for so long it only lost steam for me after the last Fu Manchu storyline then Moench’s departure under I seem to recall less then sterling circumstances (Shooter??) Looking forward to more insights.