Heavy Metal Lyrics, Sword & Sorcery Fantasy and Video Games: A Cultural Synergy by Dr. Fred Adams

Last year, Dr Fred C. Adams, Ph.D., joined our parade of writers in the Discovering Robert E. Howard series with an entry on Esau Cairn, REH’s classic science fiction character. Dr. Adams is back for another guest post here at Black Gate. Put on your headphones and go!

Last year, Dr Fred C. Adams, Ph.D., joined our parade of writers in the Discovering Robert E. Howard series with an entry on Esau Cairn, REH’s classic science fiction character. Dr. Adams is back for another guest post here at Black Gate. Put on your headphones and go!

The parallel (and almost simultaneous) ascensions of heavy metal music, video game technology (which later migrated to personal computers), and sword and sorcery fantasy to mass popularity from the early 1970s forward are not coincidental. Rather, they are synergistic. All three draw from the late 20th century youth culture’s fatalism and nihilism, honed to a fine edge in the fin de siècle era of the 1990s.

Consider the aesthetic of the Ur-arcade-video game of the 1980s, Space Invaders: ranks of grotesque aliens march across the screen as space ships fly overhead firing missiles. You, represented by a screen icon, scuttle back and forth, trapped in a small area firing and dodging missiles while trying to destroy the oncoming ranks of invaders before they reach you and symbolically stomp you into the earth.

The more you destroy, the more ranks appear, starting closer and advancing more quickly. You can forestall death for a time, but the denouement is inevitable. You will lose; the programming foreordains that you will die no matter how well or how long you fight. Other games of the era, like Missile Command, and Asteroids followed suit.

An occasional arcade game like Dragonquest allowed victory, but most reduced play to a life-and-death struggle the player will never win. The kill tally represents the only satisfaction—how many of them do I take with me? As the Time Traveler of Wells’ famous novel says of fighting an impossible number of Morlocks in the darkened forest, “I will make them pay for their meat.”

In the world of the video game, the monster/villain/antagonist may be vanquished, but he/she/it returns the next time the player enters the alternate reality; subjugated but never ultimately obliterated. The motif has its roots in mythology and the archetypal interpretations of Karl Gustav Jung.

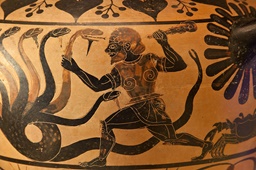

I do not wish to oversimplify Jung’s applications of archetypes to mythology (particularly hero stories) in this brief space; instead I will use an example: Heracles and the Hydra. Heracles vanquishes the Hydra by severing each of its multiple heads and searing each stump with a torch to prevent the emergence of two heads in place of the one lost.

I do not wish to oversimplify Jung’s applications of archetypes to mythology (particularly hero stories) in this brief space; instead I will use an example: Heracles and the Hydra. Heracles vanquishes the Hydra by severing each of its multiple heads and searing each stump with a torch to prevent the emergence of two heads in place of the one lost.

The final head of the Hydra is immortal, and Heracles buries it under a rock. The archetypal symbolism suggests that the Hydra represents the unconscious mind in which dwell all of the bestial, base impulses of the individual (called the Shadow by Jung), and that Heracles represents the conscious mind in which dwell order, morality, and sensibility (called the Animus by Jung). Because the two are halves of the same mind, one may overcome the other, but neither may destroy the other, so, the “evil” is subjugated but always possesses the potential to return.

A Manichaean duality results in which evil must exist so that good may have purpose.1 How entertaining would a game be that like life may be played only once? A Touch of the Reset button and the hero returns to fight, but so do his multiple antagonists; a hero with no opponent is a sword slowly rusting on a castle wall. The evil is not dead, merely lying in wait like Lovecraft’s Old Ones for the gate to open again: “That is not dead which can eternal lie . . .” heroes and villains alike.

Video games allow the warrior to return to battle again and again, a la Michael Moorcock’s eternal champion (Elric of Melnibone being only one manifestation) or Robert E. Howard’s James Allison (reincarnation of Niord, Esau Cairn, and others). It was heady stuff for a youngster to deal death with the concept that he (or she) would ultimately die but would not “go gentle into that good night”; he would slaughter his antagonists wholesale on the way out the door, like Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, perpetrators of the Columbine high school massacre.

The two were “gamers,” especially fond of the ultra-violent games Doom and Quake, and of music by Rammstein, Orbit, and Nine-Inch-Nails. While this information provides no “smoking gun” (pun intended) as to the link between video games, heavy metal and their actions, the implication is convincing.

The two were “gamers,” especially fond of the ultra-violent games Doom and Quake, and of music by Rammstein, Orbit, and Nine-Inch-Nails. While this information provides no “smoking gun” (pun intended) as to the link between video games, heavy metal and their actions, the implication is convincing.

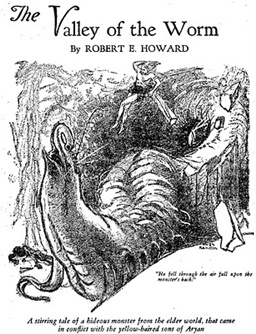

Characters like Conan, Elric, or David C. Smith’s Oron live to fight another day due to economic necessity. They are series characters and cannot be dispatched. It is in the one-time sword and sorcery heroes that we find the fatalism of the video game. An excellent example occurs in Howard’s “The Valley of the Worm.”

The progression of the novella parallels the development of play in a video game, each level becoming a greater challenge than the previous ones. The hero battles humans, then a saber-toothed tiger, then the giant venomous serpent Satha, and finally the uber-monster The Worm. Niord defeats each opponent in turn, building to the endgame battle with the ultimate monster, knowing that the only way to destroy it is to die in the process but going out in a blaze of glory.2

Film maker Roger Corman once lamented in an Esquire interview that having used the title The Losers once, he couldn’t use it again, although it offered irresistible box office bait to the teen drive-in demographic. The alienated, disaffected youth of 70s America offered a rich market for violent entertainment, a reaction to the numbing blandness of postwar life. The underdog who fights valiantly against odds that ratchet inexorably upward is an irresistible object of admiration.3

When I was a teen, my friends and I would watch the Steve Reeves Hercules films on television on Saturday afternoons. With a few exceptions (e.g. Mario Bava’s Hercules Unchained) they were dreadful cinema, but we discovered that turning off the television sound and playing loud rock music as a soundtrack, the films were fun to watch.

When I was a teen, my friends and I would watch the Steve Reeves Hercules films on television on Saturday afternoons. With a few exceptions (e.g. Mario Bava’s Hercules Unchained) they were dreadful cinema, but we discovered that turning off the television sound and playing loud rock music as a soundtrack, the films were fun to watch.

Sometimes, the combat scenes seemed almost synchronistically choreographed to songs like the Kinks’ You Really Got Me or All Day and All of the Night, the Count Five’s Psychotic Reaction, the Yardbirds’ I’m a Man, or Music Machine’s Talk Talk (arguably all forerunners of today’s heavy metal music).4 The point: spasmodic syncopated rhythms, grossly distorted guitars, and frenetic fusillades of notes made a fitting soundtrack for carnage.

Simultaneously, interest in Sword and Sorcery fantasy bloomed with the re-issue of Conan paperbacks by Ballantine Books, a renewed enthusiasm for Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings Trilogy and Fritz Leiber’s tales of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, and the emergence of newer writers in the 1970s like Karl Edward Wagner (the Kane stories), Gardner Fox (Kothar and Kyrik) and David C. Smith (Oron).

Extending the 70s trend, Marvel Comics began publishing first Conan the Barbarian as a serial comic book (1970) then spin-off anthology magazines like The Savage Sword of Conan (1974), and National Periodical Publications was publishing the serial comic book Sword of Sorcery (1973). A new young audience discovered sword and sorcery fantasy around the same time it discovered video gaming and heavy metal music, fusing the media into a unified market.

The personal computer’s multitasking capability permits a highly sophisticated game to operate on the screen while a personal music selection plays simultaneously, a customized soundtrack, if you will. Multimedia-multitasking fuses sword and sorcery fantasy with heavy metal music in the here-and-now of virtual reality.

A fourth element joined the aforementioned nihilistic, violent, and fatalistic ones: The Renewable Villain. In the late 70s, films took their cue from video gaming. The menace was only a Reset (or, if you will, a sequel) away. Customarily in earlier horror and science fiction films the monster/villain/evil was utterly destroyed, as per the vestigial film codes still inhibiting Hollywood. However, in the late 1970s, the presumed destruction of the villain as a false denouement became a staple of horror films.

A fourth element joined the aforementioned nihilistic, violent, and fatalistic ones: The Renewable Villain. In the late 70s, films took their cue from video gaming. The menace was only a Reset (or, if you will, a sequel) away. Customarily in earlier horror and science fiction films the monster/villain/evil was utterly destroyed, as per the vestigial film codes still inhibiting Hollywood. However, in the late 1970s, the presumed destruction of the villain as a false denouement became a staple of horror films.

The Tall Man of Phantasm, Freddy Krueger of the Nightmare on Elm Street flicks, Jason Voorhees of the Friday the 13th series, and Michael Myers of the Halloween movies all seemed destroyed, but leapt up at the film’s end to let the audience know that the evil was not dead, merely temporarily subjugated, a la the Hydra of the Heracles myth.5

Heavy metal lyrics support this synthesis of entertainment modes and youth culture nihilism and fatalism. In fact, bands have adopted the terms themselves as names: Fatalist and Nihilist. The genres have melded to the point that one video game, Brutal Legend, is set in a “fantasy world inspired by the artwork of heavy metal album covers” and features over 100 heavy metal songs in its soundtrack (Brutal Legend).

A sampling of heavy metal lyrics bears out the philosophical bases of nihilism and fatalism embodied by many video games, including those based on sword and sorcery themes and characters.

The following excerpt from Damage’s Hopes and Fears suggests the inevitability of death from the time of one’s birth:

Don’t fear your death watching you from the left She will warn you when she touches your face It’s your destiny, not a fantasy And it follows you from the cradle to your grave6

Warhammer’s Damned to Extinction likewise touts Man’s inescapable denouement:

We’re damned to extinction, the guilty will burn

Existence is worthless on our march into doom Man’s fate was buried long ago

Heavy metal lyrics also suggest renewable life, courtesy of the Reset button. Slayer’s Face The Slayer echoes the imagery of the inevitable death as well as the click-and-return of the resurrected hero:

You think you can destroy (me)? You’d better think again I am eternal terror my quest will never end I’ll trap you in the pentagram And seal your battered tomb Your life is just another game [italics mine] For Satan’s night of doom

Pantera’s Death Trap offers lyrics that speak of stalking and death in the form of a recurring game:

I terminate you Live by my golden rule Task complete And once again I’ve won Now I search For another victim to come

The gaming motif of the renewable hero/villain occurs in heavy metal lyrics like those of Resurrection’s Fear Factory:

Consumed with memories that preceded today

Given a chance to bereave life that’s slipping away

Suffered through tragedy of my slow decay

For the sword and sorcery devotee such imagery calls to the mind James Allison, Howard’s reincarnated hero of the aforementioned “The Valley of the Worm,” as he lies dying, wasted by age and disease recalling at his past lives:

“As I lie here awaiting death, which creeps slowly upon me like a blind slug, my dreams are filled with glittering visions and the pageantry of glory. It is not of the drab, disease-racked life of James Allison I dream, but all the gleaming figures of the mighty pageantry that have passed before, and shall come after; for I have faintly glimpsed, not merely the shapes that come after, as a man in a long parade glimpses, far ahead, the line of figures that precede him winding over a distant hill, etched shadow-like against the sky. I am one and all the pageantry of shapes and guises and masks which have been, are, and shall be the visible manifestations of that illusive, intangible, but vitally existent spirit now promenading under the brief and temporary name of James Allison.”

Granted, Resurrection’s compressed imagery lacks Howard’s articulate elan, but the vision the lyric conjures resonates with those of us who have read the Howard canon.

Slayer’s Evil Has no Boundaries also suggests the resurrection/reincarnation of the warrior:

Then we return from the dead Attacking once more now with twice as much strength We conquer then move on ahead.

In the context of video gaming, the lyric suggests the warrior’s return to the game with experience, knowledge and in the case of cumulative games, weapons, spells, and other items cached in previous “lives.”

Consider the computer itself, performing deeds that would have seemed absolutely magical a century ago, and virtual reality providing incredible milieu once restricted to passive entertainment media (films, television, radio, and reading), now interactive. Many video games permit the player to select a name and attributes (including appearance and sex) and through three-dimensional high-definition display and surround sound totally immerse the player in worlds once accessible only through books within the mind. It is sorcery whose sword is interactively taken up by the gamer, and heavy metal music is its soundtrack, the synergy of an era fusing media, motifs, mind and metal.

Works Cited

“Brutal Legend.” Wikipedia

Damage. “Hopes and Fears.” Dark Lyrics.com.

Fear Factory. “Resurrection. AZLyrics.com

Howard, Robert E. “The Valley of the Worm.”

Pantera. “Death Trap.” Dark Lyrics.com

Slayer. “Face the Slayer.” Dark Lyrics.com

Warhammer. ”Doomed to Extinction.”

Notes

- Star Wars devotees will recognize the origin of the concept of The Force

- Some may argue that the Twelve Labors of Heracles would also fit the video game template, and I agree it could make a ripping good game, but the outcome is already established by the myth, and the hero emerges alive. Further, Heracles is a demigod, not a human, and gamers

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid offers another game template motif.

- A modern manifestation is watching The Wizard of Oz while playing Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon.

- Some may argue that the Universal horror films of the 30s and 40s that allowed the return of the monsters in sequels may fall into the same category. I would suggest that in all Universal monster movies (that pesky code again) the creature/werewolf/vampire is dispatched with finality and has not resurrected itself before the final screen credits as do modern cinema menaces. The rationale, however absurd, for the monsters’ return in Universal sequels occurs in a sequel’s beginning, not at the previous film’s end. A few exceptions include Roger Corman’s classic B-flick Not of This Earth (1956) in which a new alien invader to replace the slain Paul Birch is seen lurking in the background of the final scene, or the absurd Edward Ulmer film Daughter of Doctor Jekyll (1957) that ends with a zinger following the words “THE END” in which the villain/vampire pops onto the screen and says, “Are you sure?”

- As Bob Dylan sings, “He who is not busy being born is busy dying” in It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding.

I’m of the generation you describe here, and you kinda blew-my-mind.

I got hooked on heavy metal and/or hard rock the very first time I heard Kiss’Detroit Rock City, and I got into sword & sorcery books from a more meandering path – started reading comic books at 4, which let to Tarzan, Warlord and Conan, which let to the Tarzan novels and then Ballantine’s Conan books. (I did love video games back in the arcade days, but never much went past the early 90’s Ninetindo Game console.)

But what I’m getting at; I’ve always been drawn to heavy metal music and sword & sorcery tales, as if I had no choice. Now, I’m pushing 50 and I’ve never been able to put a finger on why I’m so into that stuff, but I thing you hit-on something that kinda opens my eyes.

I’m reminded of an interesting informal analysis that purports to measure the “metalness” of words:

http://www.degeneratestate.org/posts/2016/Apr/20/heavy-metal-and-natural-language-processing-part-1/

The linguistic similarities between metal and S&S leaped out at me; I mused on it here:

http://raphordo.blogspot.com/2016/08/the-words-of-metal.html

I’ll have to give some thought to the relationship between the two and video games…

Yeah, you certainly struck a chord with me – my memories of reading Moorcock as a young teenager are inextricably intertwined with Ronnie James Dio (whose lyrics often had strong element of fantasy in them). Maybe both have the same source (and by extension, the same target audience)? Being a teenager is equated with being largely powerless in my mind, and Moorcock and Dio provided role models with which a teenage boy could identify.

In that respect, it’s interesting to compare the second wave of S&S with their principal precursor – ie, Conan. There is a very real element of post-Sixties nihilism in the way Kane and say, Elric, are depicted which again, could be very appealing to your average, frustrated teenager.

You mention how video games mimic classical myths. Interesting to see how it also works the other way re how video games have influenced popular storytelling in terms of having multiple lives, ‘Edge of Tomorrow’ being one example.