Fantasia 2016, Day 7: Immiscible Propaganda (Momotaro, Sacred Sailors; The Alchemist Cookbook; and Library Wars: The Final Mission)

As I’ve said before, sometimes the movies I see at Fantasia on a given day have a common theme. And sometimes they don’t, however much it might look like they ought to. On Wednesday, July 20, I’d go downtown to the Hall Theatre to watch an oddity: a restored Japanese propaganda cartoon from World War II, Momotaro, Sacred Sailors (Momotaro, Umi No Shinpei). Then I planned to head across the street to the De Sève and watch an independent American horror film, The Alchemist Cookbook. I hoped to make it back to the Hall after that in time to watch the second in a series of Japanese science-fiction action movies, Library Wars: The Last Mission (Toshokan Sanso: The Last Mission). It looked like a packed day, and I wondered how the movies would play off of each other.

As I’ve said before, sometimes the movies I see at Fantasia on a given day have a common theme. And sometimes they don’t, however much it might look like they ought to. On Wednesday, July 20, I’d go downtown to the Hall Theatre to watch an oddity: a restored Japanese propaganda cartoon from World War II, Momotaro, Sacred Sailors (Momotaro, Umi No Shinpei). Then I planned to head across the street to the De Sève and watch an independent American horror film, The Alchemist Cookbook. I hoped to make it back to the Hall after that in time to watch the second in a series of Japanese science-fiction action movies, Library Wars: The Last Mission (Toshokan Sanso: The Last Mission). It looked like a packed day, and I wondered how the movies would play off of each other.

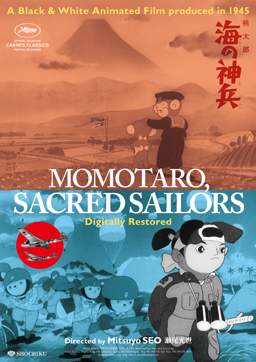

Momotaro was written and directed by Mitsuyo Seo, and released in 1945. Seo was apparently told by the Japanese Ministry of the Navy to make a propaganda film for children, and given Disney’s Fantasia as an example of what the Ministry had in mind. Seo, who’d already made a 37-short retelling the bombing of Pearl Harbour, produced the 74-minute Momotaro. It was believed lost during the American occupation, until a VHS copy turned up in Japan in the 1980s. Recently the original negatives were found, a 4K restored version was made, and Momotaro screened at Cannes in the Cannes Classics section.

Momotaro’s a mashing-up of the war in the Pacific with the Japanese legend of the peach boy Momotaro. The basic story of the tale has an elderly couple finding a boy in a peach that washes downstream past their house; when Momotaro grows up he sets out to defeat an island of demons, or oni, and does so with the help of various animal companions. Seo’s mapped that story onto the Japanese war effort in the Pacific. The movie begins with a group of anthropomorphic animals on leave from the Japanese navy and returning to their village to be celebrated as heroes. Various knockabout gags follow, and the animals join forces to save a child from falling over a waterfall. They rejoin their unit, and we see them at a navy base working and taking classes.

Then Momotaro arrives by plane. The story of Europeans invading and conquering a South Pacific island hundreds of years ago is told through silhouettes, a striking visual departure from the rest of the film. The heroic Japanese crew set out to liberate the island from the westerners, which they do following a brief but surprisingly intense battle scene. The gibbering westerners surrender — including a depressed Popeye, his can of spinach empty and rolling on the ground. Momotaro negotiates with the defeated westerners (who speak surprisingly good English). The movie ends with the childlike animals taking turns leaping from a tree onto an outline of North America sketched in the earth.

Then Momotaro arrives by plane. The story of Europeans invading and conquering a South Pacific island hundreds of years ago is told through silhouettes, a striking visual departure from the rest of the film. The heroic Japanese crew set out to liberate the island from the westerners, which they do following a brief but surprisingly intense battle scene. The gibbering westerners surrender — including a depressed Popeye, his can of spinach empty and rolling on the ground. Momotaro negotiates with the defeated westerners (who speak surprisingly good English). The movie ends with the childlike animals taking turns leaping from a tree onto an outline of North America sketched in the earth.

It’s definitely a fascinating historical document, and has been called the beginning of anime. The animation’s fluid, the black-and-white beautiful if not very high contrast. I have no idea how well it worked as propaganda in its original release. It strikes me as skilfully done, the navy life presented with enough tedium to strike a note of realism. On the other hand, the creatures in the film all work together cheerfully and without complaint. All are brave under fire, and capable in battle.

Above and beyond the navy or the war, the film praises the value of work and communal effort. Individual characterisation is relatively minimal, with an emphasis on gags. Most of the movie, more or less up until the final battle, takes place in a rural or natural world — a village or a navy camp in the jungle. Jaunty songs move the story along. There’s an odd air of good-fellowship overall. And “fellowship” is a key word; unsurprisingly enough, it’s a very male world.

Above and beyond the navy or the war, the film praises the value of work and communal effort. Individual characterisation is relatively minimal, with an emphasis on gags. Most of the movie, more or less up until the final battle, takes place in a rural or natural world — a village or a navy camp in the jungle. Jaunty songs move the story along. There’s an odd air of good-fellowship overall. And “fellowship” is a key word; unsurprisingly enough, it’s a very male world.

It’s certainly a crucial document in the history of animation. I can’t say it holds up as a film for a general audience. Of course one wouldn’t expect that of a piece of wartime propaganda, but then there are pieces of propaganda that work as narratives outside of the propaganda. It’s fair to say that the fact it holds up at all, and is in no way embarrassing, is impressive. Still, the movie feels to me like three films stitched together into one. You can see connections between the sections, but it’s essentially episodic. It is interesting as an example of myth being used for the sake of a modern story, but the Momotaro of this movie seemed to me to be too rudimentary a character to be interesting as more than an icon.

It’s imaginative, and technically impressive. The fluidity of the animation is remarkable, and the sheer amount of motion on screen is lovely. It’s a curiosity, perhaps, but as such it’s interesting.

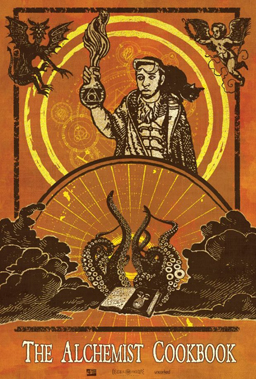

The Alchemist Cookbook was next. The title seemed to glance at The Anarchist Cookbook, but as it unfolded I couldn’t find much of a connection. Written and directed by Joel Potrykus, it’s the story of a man named Sean (Ty Hickson) who leaves society to establish himself in a trailer in the woods where he investigates occultism and alchemy. His only company is his cat, Kaspar. His only connection with the outside world is Cortez (Amari Cheatom), a relative who brings him supplies. But has Sean unintentionally raised darker forces than he wanted?

The Alchemist Cookbook was next. The title seemed to glance at The Anarchist Cookbook, but as it unfolded I couldn’t find much of a connection. Written and directed by Joel Potrykus, it’s the story of a man named Sean (Ty Hickson) who leaves society to establish himself in a trailer in the woods where he investigates occultism and alchemy. His only company is his cat, Kaspar. His only connection with the outside world is Cortez (Amari Cheatom), a relative who brings him supplies. But has Sean unintentionally raised darker forces than he wanted?

Maybe, and maybe not. The Alchemist Cookbook isn’t long, 82 minutes, and the first five or so of those minutes introduce two elements that between them make obvious what the basic structure of the movie will be. I wasn’t surprised by the way things unfolded, then, although the climax was a little bloodier than I’d expected. Without wanting to give too much away, Potrykus tries to tell a story in which Sean may be facing a diabolic power in the woods, or he may be losing his mind. I’m not convinced he manages the balancing act. Certain things, notably a seeming return to “normality” in the closing seconds of the film, strike me as impossible to explain without invoking the supernatural. On the other hand, if the supernatural is at work here, it’s even more capricious than you’d expect in a horror film.

If the plot’s obvious, does the film gain from that? I didn’t see how. There was no particular sense of ritual or inevitability that I noticed. The sense of Sean struggling with his demons, figurative or literal, was reasonably well dramatised but predictable rather than tragic. The movie unfolds in brief chapters introduced with title cards, but rather than create an inexorable feel it seemed random (especially a poorly judged break in the chapter numbering).

This is all a real pity, because the craft on display in the movie is very strong. The colours are rich, atmospheric in an unexpected way. The shots are long, brooding, and powerful. The rhythm of the film is almost elegant. The forest in late autumn is used as a deeply natural setting; it would’ve been easy to call on Halloween imagery, but Potrykus avoids that in favour of a more original approach. This is the deep forest as forest. There’s a reason Halloween became Halloween, and that’s because the season naturally calls up the feeling of things decaying and dying. Potrykus captures that in his bare-branched orange-brown leaf-carpeted forest. The days seem to get shorter as the film goes on.

This is all a real pity, because the craft on display in the movie is very strong. The colours are rich, atmospheric in an unexpected way. The shots are long, brooding, and powerful. The rhythm of the film is almost elegant. The forest in late autumn is used as a deeply natural setting; it would’ve been easy to call on Halloween imagery, but Potrykus avoids that in favour of a more original approach. This is the deep forest as forest. There’s a reason Halloween became Halloween, and that’s because the season naturally calls up the feeling of things decaying and dying. Potrykus captures that in his bare-branched orange-brown leaf-carpeted forest. The days seem to get shorter as the film goes on.

And the acting is strong. Hickson’s Sean is self-possessed, but shows more and different cracks as the movie goes along and the fear mounts. There’s a long monologue he gives to his beloved cat just before the climax where he lays out his greatest desire, to live alone in a secluded mansion with just the cat around: “No-one would ever know we were here,” he says wistfully. It’s poignant, a good emotional heart for the film.

Conversely, the slow build of increasingly surreal horror is equally effective. Characters die, or seem to, and their spirits return, or seem to. There’s something in the woods, seen at first in glances and then standing, silent. Sounds echo across the surface of a still lake. And Sean is at work with his magic, trying at first to build something and then trying to find some way to defend himself from whatever’s out there.

Conversely, the slow build of increasingly surreal horror is equally effective. Characters die, or seem to, and their spirits return, or seem to. There’s something in the woods, seen at first in glances and then standing, silent. Sounds echo across the surface of a still lake. And Sean is at work with his magic, trying at first to build something and then trying to find some way to defend himself from whatever’s out there.

But then this calls up another issue for me in the film: I didn’t notice any significant use of actual alchemical imagery. At least on one viewing, the whole paraphernalia of sulfur and mercury and Red King and White Queen seemed absent. The broad idea of working with chemicals was there, certainly, and there may well have been something I missed in the Latin Sean chanted. You could maybe argue that the trailer represented some kind of alchemical furnace, but I couldn’t see anywhere to go from there. Similarly eggs are an alchemical symbol and are crucial in Sean’s rites; but there’s not much done with that. I heard nothing in the dialogue that suggested any particular alchemical framework. Given the movie’s apparent interest in psychological effects, and Jung’s use of alchemy as representative of psychological processes, I was surprised not to see more alchemical themes. It all felt like a tremendous missed opportunity — and, since we don’t entirely grasp what Sean thinks of what he’s doing, we lack a chance to empathise with him.

If that’s lacking, what is the movie about? Clearly it has to do with alienation, with Sean’s desire to get away from society and set about his Great Work on his own. But so much of his background is left unexplored even that feels muted. Why does Sean want to get away from the world? I don’t know. If the movie’s meant to be about a solitary man becoming increasingly distanced from reality, I can’t say I buy it — the drama’s too convenient, the plot too predetermined (again, without the feeling of tragic inevitability).

If that’s lacking, what is the movie about? Clearly it has to do with alienation, with Sean’s desire to get away from society and set about his Great Work on his own. But so much of his background is left unexplored even that feels muted. Why does Sean want to get away from the world? I don’t know. If the movie’s meant to be about a solitary man becoming increasingly distanced from reality, I can’t say I buy it — the drama’s too convenient, the plot too predetermined (again, without the feeling of tragic inevitability).

On the other hand, if it can be read as arguing that retreating into one’s dreams opens the door to one’s nightmares as well, then there’s some real heft to it. Looking at the film from this angle, the question of whether the horrors visiting Sean are internal and psychological or external and occult becomes pointless. Either way, the horror’s real; either way, Sean entering his hermitage brought the horror upon himself: the woods then the crucible for his soul, or the trailer an alchemical retort. The question is whether he’s capable of the psychological discipline to master his demons.

The sheer visual style of the film means there’s an intensity to it that carries the viewer through its brief run-time. And the horror elements are absolutely effective on their own terms. It’s a scary movie. It’s also in some ways a very obvious one. And the story’s slight enough that the obviousness tends to undercut the tension — you’re waiting for events to unfurl the way you know they will. And, in due course, they do. For horror fans, and for fans of cinema as a form, there’s definite value in this movie. I’m just not convinced by it, viewed simply as a story.

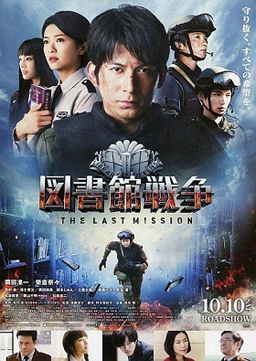

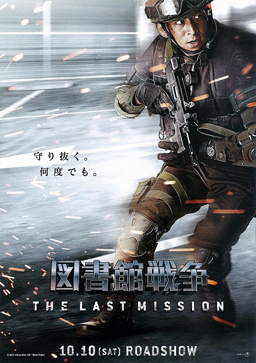

There was a question-and-answer period with Potrykus after the film. Usually I’d stick around for that and see what I could learn about what I’d just seen. In this case I didn’t. I had to get back across the street quickly to see Library Wars: The Last Mission. This was the second of a two-part film series; I’d seen the first Library Wars (Toshokan Senso) when it played Fantasia back in 2013 (before I started writing about Fantasia for Black Gate). It’d been an entertaining near-future sf/action movie, and I was hoping the second movie would be at least as good.

There was a question-and-answer period with Potrykus after the film. Usually I’d stick around for that and see what I could learn about what I’d just seen. In this case I didn’t. I had to get back across the street quickly to see Library Wars: The Last Mission. This was the second of a two-part film series; I’d seen the first Library Wars (Toshokan Senso) when it played Fantasia back in 2013 (before I started writing about Fantasia for Black Gate). It’d been an entertaining near-future sf/action movie, and I was hoping the second movie would be at least as good.

In fact, compared with my memories of the first movie, I’d say it’s much better. Interestingly, though I didn’t recall much story detail from my lone viewing of Library Wars three years ago, once the sequel started (after a video message from the director and a trailer for the Death Note sequel) it all came flooding back to me. Iku Kasahara (Nana Eikura) is a member of the Library Defense Force, a highly-trained squad of gun-packing pseudomilitary librarians struggling to defend Japan’s library system from the nefarious Media Betterment Committee. She fights for freedom of speech in a near-future dystopic Japan while trying to win the heart of her commanding officer, Atsushi Dojo (Jun’ichi Okada), the man who inspired her to join the LDF. It’s all fast, funny, and utterly engaging.

Directed by Shinsuke Sato, who helmed the first one, and like the first one written by Akiko Nagi from a light novel series by Hiro Arikawa, Library Wars: The Last Mission is credibly violent while also nodding in the general direction of character development. It’s very much an action film, albeit one with very particular rules: both the LDF and their arch-enemies the MBC are government agencies (backed by different levels of government), so their battles take place according to very formalised laws. When the MBC attacks a library they have a specific time frame by which they must win, while their use of force off library grounds is carefully circumscribed. It’s an artificial structure, yes, and very game-like, but it’s dramatic as heck, establishing clear goals for each side.

In this particular case, the last mission of the title revolves around, unsurprisingly, a book. An original printing of the 1950 Handbook of Library Law, the most sacred document of the LDF, which is about to go on display to the public (loosely based on the 1954 Statement on Intellectual Freedom in Libraries in Japan). Unless the MBC get their claws on it. Meanwhile, a subplot sees Iku accused of burning books, while a shadowy political figure schemes to undermine the LDF as a whole. Is the display of the Handbook part of his plot?

In this particular case, the last mission of the title revolves around, unsurprisingly, a book. An original printing of the 1950 Handbook of Library Law, the most sacred document of the LDF, which is about to go on display to the public (loosely based on the 1954 Statement on Intellectual Freedom in Libraries in Japan). Unless the MBC get their claws on it. Meanwhile, a subplot sees Iku accused of burning books, while a shadowy political figure schemes to undermine the LDF as a whole. Is the display of the Handbook part of his plot?

Yes, well, maybe. In fact the plot of this movie seemed much better structured than the first. As I remember, I thought the first movie was fine, but the rhythm seemed off, with action scenes and dialogue-based scenes and flashbacks creating a kind of staccato feel. That’s not the case here at all. Everything works logically to ramp up the tension. The action is (again, from memory) more plentiful than in the first movie, as much of the second film revolves around an extended siege of a vast library. Libraries in these movies are huge, great sprawling concrete brutalist structures; they have to be, to keep standing with all the bullets whistling through them. In any event, they have enough nooks and corridors to make for some very tense and very clever action sequences. And between those sequences, politics and planning sessions keep the momentum going.

This movie is not to be mistaken for a deep philosophical investigation into the nature of free speech. The two sides declaim slogans that let you know where they stand, and you can figure out who’re the good guys and who’re the baddies from that. “We must eradicate harmful books and harmful thoughts,” thunder the MBC. “When you regulate speech you’re not just striking at speech,” counters the head of the LDF. And: “A nation that burns books will one day burn men.” The evil genius behind events says, as evil geniuses inevitably must, “We will bring peace to a twisted world!” And so it goes. And so it goes.

This movie is not to be mistaken for a deep philosophical investigation into the nature of free speech. The two sides declaim slogans that let you know where they stand, and you can figure out who’re the good guys and who’re the baddies from that. “We must eradicate harmful books and harmful thoughts,” thunder the MBC. “When you regulate speech you’re not just striking at speech,” counters the head of the LDF. And: “A nation that burns books will one day burn men.” The evil genius behind events says, as evil geniuses inevitably must, “We will bring peace to a twisted world!” And so it goes. And so it goes.

It is interesting to note that the film — both films, I think — emphasise the primacy of print. Smartphones exist here, and presumably the internet, but physical books matter. They’re worth shooting and being shot over. The last physical copy of the Handbook of Library Law matters. There’s something powerful and touching in that.

The movie builds nicely through the gunplay and tension. The final action sequence pairs Iku and Dojo, as it must, and sends them on a last desperate mission together. It’s the kind of contrivance you can’t object to because it’s so effective. The climax ends in a rousing appreciation of The Power of The Press, a fitting capstone to the kind of idealism running throughout the film. They may be simple, they may be obvious, but these are movies that make you value libraries and librarians.

By the end, all loose ends are nicely tied up, and censorship has been put paid to. The last scene, of course, wraps up the romance sub-plot; well-played and well-timed, it drew cheers. That’s the kind of movie this is, and it’s as effective a movie of its type as you could possibly want. The cinematography’s solid, the editing and directing equally strong, the sense of war credible even if the final body count among the main characters is barely higher than the typical Marvel movie. (There’s no gore and little blood, either. I’m not terribly good at guessing age ranges for films, but I’d say this is perfectly viable for whatever age can take watching people firing automatic weapons at each other. Frankly, in the spirit of the film, if a younger kid wanted to watch it, I’d be tempted to let them.)

By the end, all loose ends are nicely tied up, and censorship has been put paid to. The last scene, of course, wraps up the romance sub-plot; well-played and well-timed, it drew cheers. That’s the kind of movie this is, and it’s as effective a movie of its type as you could possibly want. The cinematography’s solid, the editing and directing equally strong, the sense of war credible even if the final body count among the main characters is barely higher than the typical Marvel movie. (There’s no gore and little blood, either. I’m not terribly good at guessing age ranges for films, but I’d say this is perfectly viable for whatever age can take watching people firing automatic weapons at each other. Frankly, in the spirit of the film, if a younger kid wanted to watch it, I’d be tempted to let them.)

Library Wars: The Last Mission is exhilarating. I left the theatre with a big smile on my face, filled with the energy you get from a film that aims at entertaining you and does exactly what it set out to do in the way it set out to do it. It’s adventurous, idealistic, and very much fun.

And so the day ended. I’d seen two Japanese movies that were, one explicitly and one implicitly, propaganda for very different causes. Between them was an American movie that was more difficult to read as propaganda, being about a character who shunned society and society’s causes. What does it add up to? I don’t know. Momotaro revised myth. The Alchemist Cookbook tried something different with genre, and partially succeeded. Library Wars told a supremely well-done genre tale, a story in a sense about stories, and the freedom to tell stories. If the Fantasia festival in 2016 had been for me so far about monsters and the uses of genre, these seemed like useful pieces of the puzzle. But none of them really seemed to have much to say to each other, except perhaps as distant contrasts.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.