Fantasia 2016, Day 6: Twice-Told Tales (The Throne and The Lure)

Sometimes the movies I get to see on a given day at Fantasia have an obvious common theme. Sometimes not. Sometimes there’s a commonality binding two otherwise different movies, but it’s tenuous. So it was that on Tuesday, July 19, I watched a Korean historical drama called The Throne (originally Sado), and followed it with a Polish musical-fantasy-tragicomedy called The Lure (originally Córki dancingu). They’re both films based on older stories, in the first case recorded history from the eighteenth century, and in the second Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale “The Little Mermaid.” As you might imagine from those two very different source materials, these are very different movies in very different genres. But it also seemed to me that the process of retelling the stories was very different as well.

Sometimes the movies I get to see on a given day at Fantasia have an obvious common theme. Sometimes not. Sometimes there’s a commonality binding two otherwise different movies, but it’s tenuous. So it was that on Tuesday, July 19, I watched a Korean historical drama called The Throne (originally Sado), and followed it with a Polish musical-fantasy-tragicomedy called The Lure (originally Córki dancingu). They’re both films based on older stories, in the first case recorded history from the eighteenth century, and in the second Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale “The Little Mermaid.” As you might imagine from those two very different source materials, these are very different movies in very different genres. But it also seemed to me that the process of retelling the stories was very different as well.

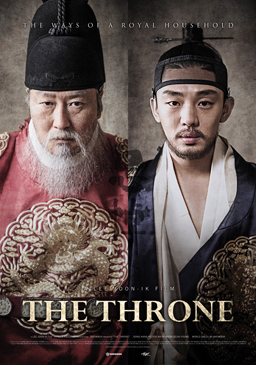

Let’s begin with The Throne, which reinterprets history in high style. Directed by Lee Joon-ik from a script by Cho Chul-hyun, Lee Song-won, and Oh Sung-hyeon, it begins one rainy night with a rebellion led by Prince Sado (Yoo Ah-in) against his old father, King Yeongjo (Song Kang-ho). It fails, and Sado’s condemned to death. The precise crime and precise punishment are determined by legalistic rules that Yeongju must follow or risk his throne; the result is that Sado’s condemned to a slow death, imprisoned in a small box without food and water. We see Sado slowly waste away, but most of the film takes place in flashback, as we learn about his life and his relationship with his father, and why he led the rebellion and why he failed.

The structure of the movie is masterful, unveiling events bit by bit. It’s not quite a mystery structure, as there’s no central investigator revealing the truth, no doubt in anyone’s mind about what’s happened or why. Instead Sado’s slow death triggers a series of memories, both Sado’s own and those of his family. As the memories accrue, we start being able to draw connections between symbols and between repeated phrases and repeated choices. Things acquire different meanings at different times. Something as simple as the choice of a gate through which the king walks, or the presence of Sado at a certain point in his father’s ritualised washing ceremony, comes to have terrible significance. We get to understand Sado, and then Yeongjo, and then Sado through Yeongjo and the way Yeongjo had to raise him.

This is a lush and detailed production, vaguely like a Korean Merchant Ivory movie in its consciousness of its own historicity — not narratively, but in its sets and props. The Joseon court had highly detailed rules for dress and hairstyle, and we see that in the costumes here. The royal palace is beautifully filmed, and the cinematography makes fine play with light and shadow: everything in the palace has a darkness to it, rich as it is. The acting is uniformly stellar, even when the emotions are so primal they must have been a challenge to present without becoming overwrought. Song Kang-ho’s Yeongjo is always closed off, except when he’s erupting in anger; Yoo Ah-in crafts an arc for Sado that goes through terrible places to the lowest nadir of all.

This is a lush and detailed production, vaguely like a Korean Merchant Ivory movie in its consciousness of its own historicity — not narratively, but in its sets and props. The Joseon court had highly detailed rules for dress and hairstyle, and we see that in the costumes here. The royal palace is beautifully filmed, and the cinematography makes fine play with light and shadow: everything in the palace has a darkness to it, rich as it is. The acting is uniformly stellar, even when the emotions are so primal they must have been a challenge to present without becoming overwrought. Song Kang-ho’s Yeongjo is always closed off, except when he’s erupting in anger; Yoo Ah-in crafts an arc for Sado that goes through terrible places to the lowest nadir of all.

It’s an intensely detailed story about family, and power, and the ways family must be sacrificed for power or the reverse. Different characters are faced throughout the movie with choices about what they value, and what they will sacrifice for what. Sado’s rebellion is very directly a willed failure, much as Yeongjo’s possession of power is a willed continuation of rule (in fact, historically Yeongjo was the longest-reigning Joseon king, so there’s a historical sense in which he may be said to be about the continuation of power). So different people are faced with the same choices, and their different actions make them different characters.

In one crucial flashback Yeongjo tells a young Sado that in the palace kings must view their children as enemies. Princes are rival powers, threats to a king’s rule, and indeed to the stability of the kingdom. This sets up what we might anachronistically call a catch-22 for Sado, in which if he makes good choices and displays talent and character he’s setting himself up as a challenger to his father, while if he does not he sets himself up as a disappointment. Sado’s tragedy is an inability to resolve this contradiction. One might perhaps go a step further and say that Yeongjo’s tragedy is in part his insistence on viewing the palace in these stark terms. We understand why he does, given the way Yeongjo came to power and the political pressures he still faces. But we also see how these pressures displaced onto Sado destroy the young prince, even to the choice of the method of his execution in the early minutes of the film.

In one crucial flashback Yeongjo tells a young Sado that in the palace kings must view their children as enemies. Princes are rival powers, threats to a king’s rule, and indeed to the stability of the kingdom. This sets up what we might anachronistically call a catch-22 for Sado, in which if he makes good choices and displays talent and character he’s setting himself up as a challenger to his father, while if he does not he sets himself up as a disappointment. Sado’s tragedy is an inability to resolve this contradiction. One might perhaps go a step further and say that Yeongjo’s tragedy is in part his insistence on viewing the palace in these stark terms. We understand why he does, given the way Yeongjo came to power and the political pressures he still faces. But we also see how these pressures displaced onto Sado destroy the young prince, even to the choice of the method of his execution in the early minutes of the film.

The closest way Sado can find to a resolution of these pressures is a kind of madness, becoming a greater and greater apostate from his father’s beliefs — literally so, in that he grows more and more religious. By the time he turns to open rebellion, he is leading his men with the name of Buddha on his lips, a contrast to his father’s strict Confucianism. But to no avail. Earlier in the film we’ve been told that: “The path cannot be diverted at any time. If it can be diverted it is not the path.” And this sums up the movie’s approach to history. We know what will happen as we watch the flashbacks. The path can’t be diverted. At best it can only be better understood.

There’s a level in which the movie’s about remembrance and the process of mourning. The slow death of Sado brings out grief in his family, of course, but one of the points of tension in the film is the way in which his mother (Jeon Hye-jin) is honoured. And one of the key elements of the resolution is how Sado himself is remembered. Given that so much of the film is flashback, memory seems a key symbolic aspect. More than that: the movie handles history for its own purpose, as drama must. The historical Sado was usually considered a raping, murdering monster, but recent reconsiderations have led to a theory that his black reputation was the result of a conscious political attempt to destroy his memory. The Throne navigates both theories, I think, showing the pressures on Sado as well as showing at least some of his violence. It interrogates memory, then, asking what memory really is. And I think the answer is that what we choose to remember is a function of who we are — and the reverse.

There’s a level in which the movie’s about remembrance and the process of mourning. The slow death of Sado brings out grief in his family, of course, but one of the points of tension in the film is the way in which his mother (Jeon Hye-jin) is honoured. And one of the key elements of the resolution is how Sado himself is remembered. Given that so much of the film is flashback, memory seems a key symbolic aspect. More than that: the movie handles history for its own purpose, as drama must. The historical Sado was usually considered a raping, murdering monster, but recent reconsiderations have led to a theory that his black reputation was the result of a conscious political attempt to destroy his memory. The Throne navigates both theories, I think, showing the pressures on Sado as well as showing at least some of his violence. It interrogates memory, then, asking what memory really is. And I think the answer is that what we choose to remember is a function of who we are — and the reverse.

Still, at one viewing, the memories that make up the film seem to align perfectly. There is no Rashomon-like sense of different perspectives with different truths. Characters are recognisably the same in personality and bearing, at least to my eye. The more we learn the more we understand the depths behind actions, as opposed to seeing contradictions in the understandings different characters have of those actions. When things are more fully remembered, they are more fully understood; and the more a character is understood, the more fit they become for remembrance by others.

The Throne is a literal and ironic title: the chair in which Yeongjo sits above all other characters, the power he has sought and for which he has sacrificed all, and then also, more bitterly, Sado forced to sit in his tiny cramped box, an ironic parody of his father’s actual throne. But then the original title, Sado, is terser and more precise. It’s about the prince, and an act of (imagined) remembrance. If it is a fictionalised reconstruction, perhaps that is true of all memories.

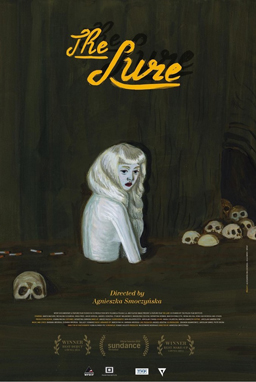

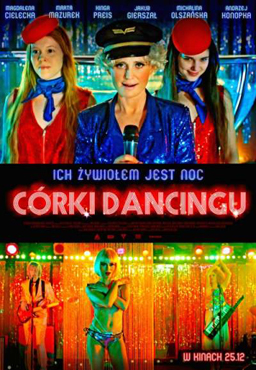

The Lure (conversely) is a fairy-tale story that radically revises its original. Directed by Agnieszka Smoczynska from a script by Robert Bolesto, it begins when two young mermaids, Golden (Michalina Olszanska) and Silver (Marta Mazurek) sing to a trio of club musicians by the waterside of Warsaw. Rather than draw the land-bound musicians to them, the mermaids end up coming ashore and becoming a part of the small family, performers in the nearby disco in an act named The Lure. Silver soon falls for the callow youngest member of the band, and you can see the outlines of the Andersen story taking shape. But what of the wilder Golden?

The Lure (conversely) is a fairy-tale story that radically revises its original. Directed by Agnieszka Smoczynska from a script by Robert Bolesto, it begins when two young mermaids, Golden (Michalina Olszanska) and Silver (Marta Mazurek) sing to a trio of club musicians by the waterside of Warsaw. Rather than draw the land-bound musicians to them, the mermaids end up coming ashore and becoming a part of the small family, performers in the nearby disco in an act named The Lure. Silver soon falls for the callow youngest member of the band, and you can see the outlines of the Andersen story taking shape. But what of the wilder Golden?

Formally The Lure is a musical, but one with an odd structure. Typically in a musical the songs not only reveal character but sum up and develop theme and plot. There is some of that here, but not much. There seemed to be a kind of fading-out of the music, or at least of the heightened reality of musical numbers, across the course of the film. There’s a sense in which that fits with the basic theme of the original Little Mermaid story, the loss of music and voice. But then there are some key differences between the original and this version of the tale, not least the addition of a second mermaid to contrast with her more lovestruck sister.

Generally both these mermaids are more formidable than traditional versions, fanged and ferocious as well as hypnotic. They can take the shape of human women, though as we are graphically shown they lack genitals: “like Barbie dolls,” an older man laconically comments. (We are also shown that this is not the case when they’re in their finned form.) In fact we get a fair amount of information about mermaids and the undersea world. Silver and Golden are not the only mercreatures in Warsaw. The price Golden must pay for love feels logical, even if this is clearly a magical fairy-tale world.

That becomes particularly interesting when we get the even-more-heightened reality of the musical on top of the fairy tale. And then the world of 80s Poland as a contrast, even as the society and theatre of the disco stands in contrast to that. There are multiple levels to this film, multiple worlds in the universe it imagines. There’s a constant tone, a kind of lighthearted sardonic look at life that includes both comedy and brutality, sometimes sadder and sometimes higher-energy. But within that tone there’s an easy moving-around within levels of reality. Even the magic that shapes the plot comes from different places; Silver gets her legs not from undersea magic, but a dingy back-alley surgeon.

That becomes particularly interesting when we get the even-more-heightened reality of the musical on top of the fairy tale. And then the world of 80s Poland as a contrast, even as the society and theatre of the disco stands in contrast to that. There are multiple levels to this film, multiple worlds in the universe it imagines. There’s a constant tone, a kind of lighthearted sardonic look at life that includes both comedy and brutality, sometimes sadder and sometimes higher-energy. But within that tone there’s an easy moving-around within levels of reality. Even the magic that shapes the plot comes from different places; Silver gets her legs not from undersea magic, but a dingy back-alley surgeon.

I don’t know whether a woman visiting a doctor outside the law for the sake of the man she loves is meant to evoke the image of an abortion, but it seems to fit with the movie’s themes of women and femininity, of idealisation and reality. Silver and Golden are very young, and this movie shows their maturation, their encounter with the ways of the surface world. The success story is the one who learns to blend her fantasies with sharp teeth, and who gives up less. There’s a musical aspect to the structural reimagining of a familiar story: there’s an added counterpoint.

I can imagine some audiences being confused by the male lead, the youth Silver falls for. He’s not given many lines, and other than youth and beauty we don’t get much of a sense of him. I think that’s the point; this isn’t his movie, and we’re seeing Silver project her aspirations onto him, imaginning him as better than he is. In fact he’s brutally direct in his contempt for her in her original form, and is repelled even after she sacrifices for him — turned away by the unexpected presence of blood in her nether regions, whether as artifact of surgery or of real womanhood. The story’s pointed, the themes directly brought out.

I can imagine some audiences being confused by the male lead, the youth Silver falls for. He’s not given many lines, and other than youth and beauty we don’t get much of a sense of him. I think that’s the point; this isn’t his movie, and we’re seeing Silver project her aspirations onto him, imaginning him as better than he is. In fact he’s brutally direct in his contempt for her in her original form, and is repelled even after she sacrifices for him — turned away by the unexpected presence of blood in her nether regions, whether as artifact of surgery or of real womanhood. The story’s pointed, the themes directly brought out.

What did seem to me to be the main problem with the movie is its predictability. That’s odd for a film that’s in many ways stunningly original. The problem is a little like what C.S. Lewis (if I remember right) once said about Kafka’s Metamorphosis: the actual book doesn’t add more than what you get from a brief synopsis of the story. The thing in full realisation doesn’t much improve on the idea of the thing. In this case, if you say “a feminist retelling of ‘The Little Mermaid’ with a more rebellious sister mermaid” you can see more or less where the story goes. Narratively, there’s not a lot surprising in the general contours of the plot.

The reason this works is because so much else is so original. The story becomes a kind of guide, something we can follow even if we’re swept away by other strangeness. Narrative can be predictable, but songs and pacing and acting choices and directorial choices are surprising. In particular, the script is very terse; the visual storytelling is a whirl, kinetic as musicals are, a mad reel of colour and camera angles. The familiarity of the story keeps us as it were anchored through the unpredictable. And there are new things here, mostly seen through Golden and her contrast to Silver. The sheer experience of watching the film is so rich, so filled with the new, that the armature of the old plot is useful.

The reason this works is because so much else is so original. The story becomes a kind of guide, something we can follow even if we’re swept away by other strangeness. Narrative can be predictable, but songs and pacing and acting choices and directorial choices are surprising. In particular, the script is very terse; the visual storytelling is a whirl, kinetic as musicals are, a mad reel of colour and camera angles. The familiarity of the story keeps us as it were anchored through the unpredictable. And there are new things here, mostly seen through Golden and her contrast to Silver. The sheer experience of watching the film is so rich, so filled with the new, that the armature of the old plot is useful.

There were two films at Fantasia this year that left me dazed and looking around in wonder when the lights went up, a little surprised to find myself after all in a movie theatre. This was one of them. I think the sheer energy of the storytelling, the pacing of it linked with its taut dialogue, drew me into it more than I consciously realised while it was happening. The Lure is a visual and auditory accomplishment, a rhythmic and exhilarating pleasure.

Two different ways to tell old stories. Both structurally inventive. One consciously revising its source, the other investigating the texture of the historical moment. Both effective (worth noting that The Lure presumably had a much smaller budget than The Throne, and accomplished a lot with it). There’s a lot you can do when you rewrite an old story, and much a talented director can bring to it.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

The old royal palaces in Korea would make stunning film settings. It’s been a long time since I saw them, but I remember striking contrasts of small intimate spaces with grandly performative large ones, and everywhere gardens and enclosing courtyards to complicate the sight lines. Picturing the story you describe from The Throne in any of them makes me want to rush to Netflix and urge them to license it.