Fantasia 2016, Day 5: Bewitched and Bewailing (The Love Witch and The Wailing)

I had only one movie on my schedule for Monday, July 18, but thanks to the good offices of the people at the Fantasia Film Festival and at Oscilloscope Laboratories, I ended up able to catch another film first. The Love Witch was a movie that I’d been unable to watch in its theatrical showing at Fantasia due to a scheduling conflict. After seeing it Monday, I’d go on to the Hall Theatre for The Wailing (Goksung), a two-and-a-half hour Korean horror film. The movies made for an odd contrast. In both cases I greatly appreciated them but came away fairly sure I wasn’t part of their primary audience. But movies play to whoever sees them, and perhaps writing about these films will bring them to the attention of people with better perspectives than my own.

I had only one movie on my schedule for Monday, July 18, but thanks to the good offices of the people at the Fantasia Film Festival and at Oscilloscope Laboratories, I ended up able to catch another film first. The Love Witch was a movie that I’d been unable to watch in its theatrical showing at Fantasia due to a scheduling conflict. After seeing it Monday, I’d go on to the Hall Theatre for The Wailing (Goksung), a two-and-a-half hour Korean horror film. The movies made for an odd contrast. In both cases I greatly appreciated them but came away fairly sure I wasn’t part of their primary audience. But movies play to whoever sees them, and perhaps writing about these films will bring them to the attention of people with better perspectives than my own.

Directed and written by Anna Biller, The Love Witch is a mix of horror, satire, and melodrama which follows Elaine (Samantha Robinson), a witch and murderess, as she moves to a new home and seeks love. Unfortunately for the men she desires, she’s both unforgiving and possessed of high standards. Any sign of weakness or emotional neediness is a sign of her partner’s unfitness, which she puts to an end both swift and fatal. Will Elaine finally find the man of her dreams? Or will her interest in Richard (Robert Seeley), the husband of her friend Trish (Laura Waddell), bring about her downfall?

From the opening shots of a bright scarlet car driving along a California highway we know this is going to be a stylish treat for the eyes. Biller’s created a colour-drenched world out of a Hollywood melodrama, circa 1970. It isn’t set in that time — we get a few signs to the contrary, mostly in scenes involving policemen trying to figure out where all the dead male bodies are coming from — but it’s largely played that way, with sets and props evoking the period. More than that, there’s a mannered artificiality to the acting styles and dialogue that (I felt) mimics the specific artificiality of the late 60s.

The film is, of course and inevitably, terribly ironic. But the irony and the self-consciousness of the film still leave much open for interpretation. One of the fascinating, and indeed engaging, aspects of the movie is how it seems to invite multiple readings. How seriously is one to take any given element? Is Elaine hero or monster, self-actualised or brainwashed by stereotypes? Is witchcraft a salvific feminist power, or a delusive tool of men and patriarchy? Do we stand at a distance and laugh at the characters, or do we invest in their melodrama? It’s quite possible different viewers will have different answers to these questions, or the same viewer will have different answers after different viewings.

The film is, of course and inevitably, terribly ironic. But the irony and the self-consciousness of the film still leave much open for interpretation. One of the fascinating, and indeed engaging, aspects of the movie is how it seems to invite multiple readings. How seriously is one to take any given element? Is Elaine hero or monster, self-actualised or brainwashed by stereotypes? Is witchcraft a salvific feminist power, or a delusive tool of men and patriarchy? Do we stand at a distance and laugh at the characters, or do we invest in their melodrama? It’s quite possible different viewers will have different answers to these questions, or the same viewer will have different answers after different viewings.

Questions aside, what stood out to me after one viewing was the theatrical use of colour to establish character, and the way that worked powerfully with theme and story. It’s a beautiful and knowingly artificial film, and so is its main character. Elaine constructs herself visually like an actress preparing a role, with clothes and make-up and a wig — all of it designed for an effect on her audience (of men). The movie about Elaine, on the other hand, echoes her attempt to create glamour by building a glamorous world for a different audience (presumably of women). It’s a classic Hollywood glamour, a stylistic approach that fits Elaine perfectly while advertising its own artificiality and hers. And, of course, it invites us to think about the different meanings of the word “glamour” — a kind of beauty associated with classic Hollywood, but also a kind of magic.

In fact Biller subverts the highly romantic and theatrical patina of her film at several key points. Elaine weaves one magic spell using her menstrual blood, for example, a note of corporeal reality that’s deliberately out of tune with the glossy construction of femininity the film otherwise evokes. More than that, as the movie goes on it increasingly refers to twenty-first-century psychological ideas to explain its characters. There is perhaps a risk of presentism in this, giving the habits of thought of the current day too much weight, but it does effectively puncture the fantasy-world of true love Elaine’s built for herself.

Which is in turn an odd construction. Elaine doesn’t seem to distinguish between love and sex, a hint that she’s internalised some very patriarchal ideas. She’s dramatically interesting because she knows what she wants and goes after it. She’s clearly the driver of her own story. Her problem is that the story is one that’s been handed down to her, and that she has not revised for herself. (It is tempting to think that The Love Witch as a film represents Biller more consciously revising the tradition of women’s stories handed down to her, but that’s probably overreaching.)

On the other hand, at one point we hear Elaine’s lover Griff (Gian Keys), who is also her nemesis on the police force trying to solve her killings, think to himself that love is an emasculating force which he rejects. He wants merely a wife and an heir. It sounds archaic, patriarchal in the original bronze age sense, but then at the time he and Elaine are surrounded in the make-believe world of a troupe of medieval reenactors (who perhaps evoke courtly love as a contrast; if so, an interesting ambiguity, given the different ways courtly love can be read, and its possible connection with Eleanor of Aquitaine’s supposed Court of Love).

On the other hand, at one point we hear Elaine’s lover Griff (Gian Keys), who is also her nemesis on the police force trying to solve her killings, think to himself that love is an emasculating force which he rejects. He wants merely a wife and an heir. It sounds archaic, patriarchal in the original bronze age sense, but then at the time he and Elaine are surrounded in the make-believe world of a troupe of medieval reenactors (who perhaps evoke courtly love as a contrast; if so, an interesting ambiguity, given the different ways courtly love can be read, and its possible connection with Eleanor of Aquitaine’s supposed Court of Love).

Not long after, Griff’s casual use of a cell phone throws us back to the present day: by implication his thinking isn’t meant to be period sexism. Nor is that utilitarian view of women and sexuality the only tradition of patriarchal sexual desire we see. Earlier in the film an academic takes Elaine to his isolated cottage where he has a library of eighteenth-century pornography — Casanova and Fanny Hill and (ironically enough) Dangerous Liasons, although apparently no De Sade. The tradition of libertinism, in other words, and it’s hard not to think that it’s brought in here to echo and satirise rhetoric of sex as revolution or enlightenment, sex as liberation and liberation as sex with no distinction drawn.

You can argue that the movie gets too simple in its satire at some points. That’s an occupational hazard of satires. There’s a scene in which one of Elaine’s victims tells her about his dreams of escape and power, and they’re fantasies specifically out of Hollywood movies — Steve McQueen, Western baddies. “Poor baby,” coos Elaine, “poor poor baby,” infantilising him as a means of seduction. The scene’s incisive, but also obvious on a character level. You start wondering why Elaine never runs into any man who’s at least a little self-aware. The answer is, because this isn’t that kind of movie; the characters here, man or woman, aren’t about self-awareness.

In fact, Elaine as a character plays around with old archetypes, aspiring to simplicity, to being something out of story and indeed out of fantasy. The witch as icon of power, but also witch as monster. The witch as initiate into divine mystery who uses her uncanny knowledge for ill intent. She largely succeeds, for better or worse. Robinson’s remarkable performance sells that, uniting the sense of archetype with a kind of classic movie-star acting. She creates a performance that’s all surface, as so much of the movie is all surface, and yet implies ironic depth, as so much of the movie is, to me, ironic.

In fact, Elaine as a character plays around with old archetypes, aspiring to simplicity, to being something out of story and indeed out of fantasy. The witch as icon of power, but also witch as monster. The witch as initiate into divine mystery who uses her uncanny knowledge for ill intent. She largely succeeds, for better or worse. Robinson’s remarkable performance sells that, uniting the sense of archetype with a kind of classic movie-star acting. She creates a performance that’s all surface, as so much of the movie is all surface, and yet implies ironic depth, as so much of the movie is, to me, ironic.

All of which is to say that she sells Elaine’s limits. Dark and old as Elaine’s narrative antecedents are, she also frequently sounds like a parody of a Cosmopolitan article. “According to the experts,” she reflects early on, “men are very fragile. They can get crushed down if you assert yourself in any way. You have to be very tricky.” She’s mirroring male ideas about women’s sexuality back to society, but a mirror has no real depth. She explains to Trish in an early scene what (she thinks) men want, only for Trish to ask in response “what about what we want?” Of course Elaine’s got no ready answer; she’s not capable of that kind of self-reflection.

She has crafted (so to speak) herself into a man’s fantasy of a woman, or at least a woman’s idea of a man’s fantasy of a woman. She’s happy to proclaim to one of her intendeds that “I’m the Love Witch! I’m your ultimate fantasy!” And yet male fantasies of witches have a darker edge to them: “What a pussy!” she sneers to herself when one of her conquests (there is no other appropriate word) breaks down after sex. The gendered insult tells us how deeply she’s internalised patriarchal values, sure, and yet at the same time it’s drawing on ideas of cold-hearted witches fed by patriarchal fears. If she’s a monster to men, she’s a monster men have imagined: the White Goddess, la belle dame sans merci.

She has crafted (so to speak) herself into a man’s fantasy of a woman, or at least a woman’s idea of a man’s fantasy of a woman. She’s happy to proclaim to one of her intendeds that “I’m the Love Witch! I’m your ultimate fantasy!” And yet male fantasies of witches have a darker edge to them: “What a pussy!” she sneers to herself when one of her conquests (there is no other appropriate word) breaks down after sex. The gendered insult tells us how deeply she’s internalised patriarchal values, sure, and yet at the same time it’s drawing on ideas of cold-hearted witches fed by patriarchal fears. If she’s a monster to men, she’s a monster men have imagined: the White Goddess, la belle dame sans merci.

It’s entirely possible, I think, to see the movie as a tragedy with Elaine’s fatal flaw her inability to conceptualise her own goals — in fact, Biller has commented that she hopes other women will identify with Elaine as she does. Personally, I found the alienation caused by the deep irony of the movie was mostly overcome by the fact that Elaine wants something so clearly and goes after it so strongly. To me, that’s what fosters identification. Elaine’s after true love. In a way that means she’s out for her own pleasure, like one of those eighteenth-century libertines, but her lack of self-awareness means she’s defined that pleasure according to the ideals of the men in her life. Flashbacks to Elaine’s relationship with her ex-boyfriend Jerry (no, I don’t think there’s a reference to Seinfeld intended with Elaine and Jerry and yes, I’m distracted enough to wish at least one name had been different) and with her father show us how she’s in fact been moulded in central ways by the men in her life. Her self-realisation, her liberation, is circumscribed by this unconscious programming.

And yet, the film acknowledges the power of the image of the witch. That’s fair; this is why the movie exists in the first place, that image and its resonance. When Trish sneaks into Elaine’s home late in the movie, and looks at herself in Elaine’s mirror, and tries on Elaine’s clothes, before finally uncovering one of Elaine’s terrible secrets — we’re seeing a playing-about with gothic plot conventions going back to the eighteenth century, maybe, but we’re also seeing the fascination Elaine’s power has for another woman. Trish, at least briefly, identifies with Elaine and her seeming perfection. But is this identification a source of power or a flight from reality?

And yet, the film acknowledges the power of the image of the witch. That’s fair; this is why the movie exists in the first place, that image and its resonance. When Trish sneaks into Elaine’s home late in the movie, and looks at herself in Elaine’s mirror, and tries on Elaine’s clothes, before finally uncovering one of Elaine’s terrible secrets — we’re seeing a playing-about with gothic plot conventions going back to the eighteenth century, maybe, but we’re also seeing the fascination Elaine’s power has for another woman. Trish, at least briefly, identifies with Elaine and her seeming perfection. But is this identification a source of power or a flight from reality?

Answering this question raises another related question. What exactly is witchcraft in this movie? It’s a source of Elaine’s power, clearly. It’s something that actually works as a way to bring about transformation in accordance with the will. And it’s clearly based in Wicca, paganism, and ceremonial magic; one of Elaine’s grimoires contains Aleister Crowley’s line that “Every man and woman is a star.” Members of Elaine’s old coven appear in the film, and we see some of their rites, at least one of which seems to be a version of a Black Mass. That sits oddly with the otherwise more purely pagan approach that the characters elsewhere articulate, but then one of them does grumble about the days when Wicca and Satanism and Druidism and all other forms of occultism were mixed freely.

Which also may be a hint from the movie to not try to tie it too closely to any one faith tradition. And that’s fair enough, up to a point. But the cinematic witchcraft here has close parallels to real beliefs; I can imagine some members of relevant traditions finding the film either particularly disturbing or (perhaps) empowering (I’ll note I found one review by a pagan praising the film and Biller’s research). Either way, I personally felt the movie was occasionally caught in an unacknowledged tension between witchcraft as metaphor and witchcraft as, within the story, a literally effective force. Elaine isn’t all-powerful, but her potions do seem to operate just as she wants. If that’s so, shouldn’t we look at witchcraft in the film as having a particular truth? And how to read a subplot in which locals immediately tie Elaine’s murders to witchcraft? “It’s them witches again!” someone exclaims when a dead man’s found; in this film, there’s tension between witches and everyday people, to the point where mobs of the latter occasionally form to attack the former. But this is a witch panic based in real self-preservation — there actually is at least one witch actually killing people. To me the conscious unreality of the film felt stretched a little too far around this point.

Which also may be a hint from the movie to not try to tie it too closely to any one faith tradition. And that’s fair enough, up to a point. But the cinematic witchcraft here has close parallels to real beliefs; I can imagine some members of relevant traditions finding the film either particularly disturbing or (perhaps) empowering (I’ll note I found one review by a pagan praising the film and Biller’s research). Either way, I personally felt the movie was occasionally caught in an unacknowledged tension between witchcraft as metaphor and witchcraft as, within the story, a literally effective force. Elaine isn’t all-powerful, but her potions do seem to operate just as she wants. If that’s so, shouldn’t we look at witchcraft in the film as having a particular truth? And how to read a subplot in which locals immediately tie Elaine’s murders to witchcraft? “It’s them witches again!” someone exclaims when a dead man’s found; in this film, there’s tension between witches and everyday people, to the point where mobs of the latter occasionally form to attack the former. But this is a witch panic based in real self-preservation — there actually is at least one witch actually killing people. To me the conscious unreality of the film felt stretched a little too far around this point.

In general the movie seems to quarry pagan and occult faiths for themes, but is more engaged with ideas around those traditions than with the traditions themselves. We get speeches about the power of women’s sexuality, but a man is still leader of the coven: the implication seems to be that patriarchy’s still at work even in witchcraft. The ideas are put forward and undercut at the same time. Sex and power are spoken about in terms at once elevated and abstracted, even flattened. The witches are people looking for an escape, but it is a negative escapism, a retreat. Like the libertine academic, flight based in sexuality does not lead to self-realisation.

I note that in the press kit I’ve already linked to Biller says that: “the witchcraft setting … [is] a world of people turning desperately to spells and magic to get what they want, after they’ve lost confidence in their own lives.” It is possible in context to read this statement as referring specifically to the witchcraft setting in the movie, but I’m not convinced we get enough information about the witches’ lives as a group for this to be clear. I do think there is a clear sense in the movie that witchcraft is a kind of escapism, or at best idealism with severe limitations. And yet, it’s also a magic that works. Perhaps it can be put this way: witchcraft in this movie is the ideology that produces Elaine, and whatever damage Elaine had when she came to witchcraft, the belief system is still implicated in her limitation.

That’s almost a paradox: a highly-worked, highly-stylised fiction suspicious of another kind of reimagining of reality because it reimagines reality. It isn’t, in these sense that the film’s vision contains and critiques the other (to be pedantic: the film’s vision contains a vision it identifies with the concept of ‘witchcraft’). And yet, again, the power of witchcraft is, in the story of The Love Witch, real and undeniable and accessible. As a result, I would say that the ending of the film is more inconclusive than it appears. The ostensible tragedy can be read different ways, depending on how much magic you think Elaine has.

That’s almost a paradox: a highly-worked, highly-stylised fiction suspicious of another kind of reimagining of reality because it reimagines reality. It isn’t, in these sense that the film’s vision contains and critiques the other (to be pedantic: the film’s vision contains a vision it identifies with the concept of ‘witchcraft’). And yet, again, the power of witchcraft is, in the story of The Love Witch, real and undeniable and accessible. As a result, I would say that the ending of the film is more inconclusive than it appears. The ostensible tragedy can be read different ways, depending on how much magic you think Elaine has.

How to take the film as a whole, then? Many ways, I think. I’d say there’s obviously a strong indictment of patriarchal values in it, and I’d say that indictment’s dramatised in a number of effective ways. For example, there’s a very strong central insight implied about relationships: if love is based on a struggle for dominance, however covert, then once the struggle ends so does love. I would also say that the form of the movie, the artificiality of the world and the performances, matches and expands on the content; it brings out the artificiality of the ideals the characters live. Above all, I’d say that this is a supreme technical accomplishment that is narratively involving even as it makes use of estrangement effects. Someone more knowledgeable than I about film history would no doubt be able to write insightfully about its state as a woman’s movie that plays with traditions of women’s films and images of women. I can only say that it’s thought-provoking, visually striking, often funny, and ultimately entertaining.

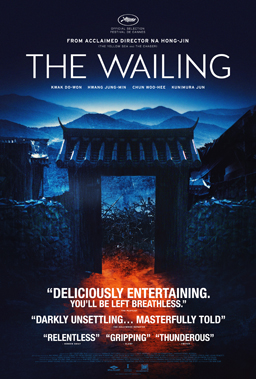

Down at the Hall theatre, The Wailing would make an interesting contrast. A short film screened beforehand, “Pyotr495,” written and directed by Blake Mawson. It’s a stylish short about a gay youth in Russia who plans to meet up with another man he meets online. The encounter does not go the way he hoped, and everyone involved gets more than they expected, mostly in horrific ways. It’s visually striking, with an unsettling use of colour, but it’s not terribly surprising on a plot level. Indeed it feels like an old issue of The Incredible Hulk, given a twenty-first-century polish to include issues like homophobia and anti-immigrant hate. Which is to say it has a heart, but lacks a horrific punch. In which latter it was much unlike the feature that followed.

Down at the Hall theatre, The Wailing would make an interesting contrast. A short film screened beforehand, “Pyotr495,” written and directed by Blake Mawson. It’s a stylish short about a gay youth in Russia who plans to meet up with another man he meets online. The encounter does not go the way he hoped, and everyone involved gets more than they expected, mostly in horrific ways. It’s visually striking, with an unsettling use of colour, but it’s not terribly surprising on a plot level. Indeed it feels like an old issue of The Incredible Hulk, given a twenty-first-century polish to include issues like homophobia and anti-immigrant hate. Which is to say it has a heart, but lacks a horrific punch. In which latter it was much unlike the feature that followed.

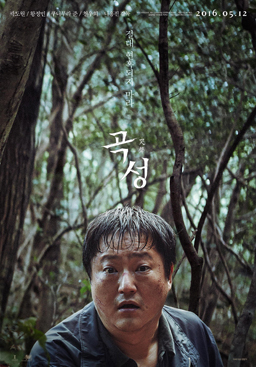

The Wailing, written and directed by Na Hong-jin, opens with a title card quoting the gospel of Luke, affirming the concrete reality of the resurrected Christ. The point is to place us firmly in a world of physically tangible spiritual forces; the first images we get, of an old man fishing alone at dawn, therefore necessarily carry symbolic weight. This is a fisher of men, but who is he? For much of the 156 minutes that follow, we and the characters must struggle to work that out.

The lead character’s a policeman named Jeon Jong-gu (Kwak Do-won) in the village of Goksung, where the police are suddenly busy dealing with horrific crimes rocking the town. There’s a double-murder with ritual elements. A fire with three more bodies and two furious mutilated survivors. These horrors are balanced against scenes from Jeon’s everyday life; he’s a family man, a pudgy bumptious none-too-brave sergeant who we quickly see is out of his depth faced with the viciousness of the crimes. And with the multiplicity of suspects. There’s an old Japanese man living on his own in the woods (Jun Kunimura, also in the Parasyte movies at this year’s Fantasia, among many other films). A strange close-mouthed woman dressed in white (Chun Woo-hee, star of Han Gong-ju). Who’s responsible for what?

There’s a real warmth to the first part of the movie, balanced against the village tragedies. The balance slowly tips as the film goes on. A widespread skin rash breaks out. Then Jeon’s daughter (Kim Hwan-hee) falls ill with something that looks awfully like demonic possession. A shaman (Hwang Jung-min) and a young Catholic priest (Kim Do-yoon) are brought in. Jeon gets increasingly desperate. The horror grows ever more undeniable, the pressure mounting bit by bit. Tales are told. Dreams, or nightmares, are dreamed; how do you tell them apart from reality? Bit by bit we leave the real world, bit by bit we come to appreciate that Goksung has become the battleground for powers and principalities. Jeon and his family have the bad luck to be front and centre in this struggle, where the weapons are unclear and the battle-lines uncertain.

There’s a real warmth to the first part of the movie, balanced against the village tragedies. The balance slowly tips as the film goes on. A widespread skin rash breaks out. Then Jeon’s daughter (Kim Hwan-hee) falls ill with something that looks awfully like demonic possession. A shaman (Hwang Jung-min) and a young Catholic priest (Kim Do-yoon) are brought in. Jeon gets increasingly desperate. The horror grows ever more undeniable, the pressure mounting bit by bit. Tales are told. Dreams, or nightmares, are dreamed; how do you tell them apart from reality? Bit by bit we leave the real world, bit by bit we come to appreciate that Goksung has become the battleground for powers and principalities. Jeon and his family have the bad luck to be front and centre in this struggle, where the weapons are unclear and the battle-lines uncertain.

The Wailing is a beautiful movie. The sense of light and colour, of light and shade, is precisely right: realistic, and yet also more striking than merely real. The natural world, from the opening scenes of the fisherman onward, is a place of sublimity: beauty, then, but also by implication terror in the shadows of the woods. It seems to me, looking back on the film, to grow darker as it goes along, those shadows building to a final night filled with horror and uncertainty. Certainly the storytelling is perfect yet understated, the timing of the edits just right whether in scenes of tension, or a magical rite, or setting up an unexpected gag.

Because this is also, at times, a very funny movie. Early on Jeon seems like a Lou Costello stuck in a serious horror film bereft of Bud Abbott. Later he came to feel to me oddly like Jackie Gleason’s Ralph Kramden: big and bumptious, cowardly but warm-hearted. He’s not nearly that extroverted, but Kwak Do-won’s ability to mix comedy with a deep sense of character gives us an always involving and surprising protagonist.

Because this is also, at times, a very funny movie. Early on Jeon seems like a Lou Costello stuck in a serious horror film bereft of Bud Abbott. Later he came to feel to me oddly like Jackie Gleason’s Ralph Kramden: big and bumptious, cowardly but warm-hearted. He’s not nearly that extroverted, but Kwak Do-won’s ability to mix comedy with a deep sense of character gives us an always involving and surprising protagonist.

The story of the film was, at points, less clear to me. Some of that was deliberate. Some of it I’m not sure about. At this point I should state clearly what is probably obvious: I’m reviewing The Wailing (and of course all the other films at Fantasia) as a white North American. I don’t have a particularly deep knowledge of Korean culture or (especially) Korean religion. In the particular case of this movie, I’ve gone online and tried to find out what I may have missed — partly out of a sense of fairness, and partly because what I did get was enough to leave me curious. I’ve read some explanations from various sources. Notably, I’ve read some comments by the director on his own work. Most of what I found was clear enough in the theatre. Whether there’s more to grasp is necessarily something I can’t know. A response to a film is always an individual response conditioned by an individual’s knowledge, but in this case that may be particularly pointed.

This is all by way of saying that while the overall narrative thrust of the movie was clear enough to me, the last twists in the final moments didn’t immediately make sense. Or, at least, didn’t make quite enough sense. I’ve seen any number of horror films that build to a final negative revelation, an unveiling of the truth that makes the audience re-evaluate everything they’ve seen up to that point. The Wailing tries to do that, but I’m not convinced it pulls off the trick. Done right, the technique acts like the toppling of a line of dominos: one line drops on us like the first domino to fall, knocking down what we thought we understood about the rules of the world, more and more the more we think about it, piece toppling piece in a series of clicks, until a new picture is revealed underneath. Here we get the facts, but half the dominos don’t fall over. I was left with a lot of confusion. If this is that, why didn’t this character tell that character what was happening? If this character is really such-and-such, why did they act in a certain way when nobody was around to see them?

This is all by way of saying that while the overall narrative thrust of the movie was clear enough to me, the last twists in the final moments didn’t immediately make sense. Or, at least, didn’t make quite enough sense. I’ve seen any number of horror films that build to a final negative revelation, an unveiling of the truth that makes the audience re-evaluate everything they’ve seen up to that point. The Wailing tries to do that, but I’m not convinced it pulls off the trick. Done right, the technique acts like the toppling of a line of dominos: one line drops on us like the first domino to fall, knocking down what we thought we understood about the rules of the world, more and more the more we think about it, piece toppling piece in a series of clicks, until a new picture is revealed underneath. Here we get the facts, but half the dominos don’t fall over. I was left with a lot of confusion. If this is that, why didn’t this character tell that character what was happening? If this character is really such-and-such, why did they act in a certain way when nobody was around to see them?

The overall drift is clear enough. I understood most of it in the theatre, or put it together thinking about it on the walk home later that night. What I found online tended to reinforce the ideas I already had. So that extent, I’d say the film is a success. But I didn’t think the final revelations aligned as perfectly as was needed.

There is a valid argument that this is in part the point. I think the movie’s a film about the mystery of the divine. We’re stuck in a world with good and evil, but our ability to perceive these things is not as clear as we think. We flail around, but are tragically limited in our understanding. The Wailing is then about the horror of not knowing, about the epistemology of the sacred. And about how faith is most needed when there’s absolutely no reason for faith — faith not in the face of reason but of randomness. Is this entity good or bad? Believe or don’t. Your call, but in this movie your life and the life of your loved ones may depend on it. Guess wrong and be damned.

There is a valid argument that this is in part the point. I think the movie’s a film about the mystery of the divine. We’re stuck in a world with good and evil, but our ability to perceive these things is not as clear as we think. We flail around, but are tragically limited in our understanding. The Wailing is then about the horror of not knowing, about the epistemology of the sacred. And about how faith is most needed when there’s absolutely no reason for faith — faith not in the face of reason but of randomness. Is this entity good or bad? Believe or don’t. Your call, but in this movie your life and the life of your loved ones may depend on it. Guess wrong and be damned.

Jeon’s a great character to have in the lead: neither stupid nor particularly clever, a good man but flawed, he’s in a job that makes him a seeker after truth. But he’s not very good at his job. He’s easily scared, meaning he flinches away from the most uncomfortable of those truths. He’s an agent of the moral law, but far from morally incorruptible himself; the more he’s pushed, the more he abuses his position and gets physically violent with people who, on the face of it, don’t deserve it. What’s attractive about him, though, is that wrath is less his primary sin than sloth. It reminds me of the theory about Satan’s attractiveness in Paradise Lost: we’re drawn to the corrupt character because we recognise our corruption in him. In a spiritual world, dramatic imperatives are a function of a fallen nature. If you seek something it is because you lack it, and if you lack something then you’re clearly not living in Eden or paradise; story is is a sign of alienation from the divine, and moral failures in a character emphasise their dramatic nature.

If I seem to be emphasising Christian concepts here, I’ll note again that I’m predisposed by background to spot them in the film — I wasn’t raised in a specifically Christian tradition, but it’s part of the intellectual furniture of the society I grew up in. And it’s part of the conceptual background of the film, right from the opening title card. Yet there are also clear syncretic aspects to the film as well; as I’ve noted, Korean shamanic practice plays a major role in the story. It is possible to read certain entities as spirits from either tradition. Again, there is an uncertainty less in the mind of the filmmaker than in what the characters and perhaps the audience can know. And there is an unimportance to it, I think. You can call salvation and damnation by whatever names you like, impose whatever conceptual apparatus you like upon them. You have the faith or you don’t.

I want to emphasise that you don’t need to know Korean culture to see beauty and meaning in The Wailing. More knowledge might well bring more understanding or appreciation of the film, but then one can say that about almost any work of art. It’s a horror movie that engages more seriously than most with the implications of horror — the spiritual dimensions of a world with demons in it, and why mortals fall prey to demons. It’s a strong accomplishment. But, while I recognise the value and power of ambiguity, I’m not sure the specific ambiguities at work in this movie always make it stronger.

I want to emphasise that you don’t need to know Korean culture to see beauty and meaning in The Wailing. More knowledge might well bring more understanding or appreciation of the film, but then one can say that about almost any work of art. It’s a horror movie that engages more seriously than most with the implications of horror — the spiritual dimensions of a world with demons in it, and why mortals fall prey to demons. It’s a strong accomplishment. But, while I recognise the value and power of ambiguity, I’m not sure the specific ambiguities at work in this movie always make it stronger.

As I said above, The Love Witch and The Wailing make for a fascinating contrast. Both are intensely stylish films, the first constructing a highly artificial reality while the second draws out every least bit of sublimity within the complexity of the natural world. The first takes a very ironic approach to faith, the second immerses itself within multiple traditions. The first implies that fantasies, faith-based or otherwise, are escapes from reality. The second implies that reality is permeable, at the mercy of the interpretation of the unnatural and fantastic. Both are genre works, but genre’s deployed to different ends, self-critique on the one hand and a kind of revelation on the other. There are monsters at the heart of both these different labyrinths. And the ways we identify with these monsters are in both cases complex; how we see them says much about our own selves.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

When it comes to new movies trying to replicate a old movie type of Femme Fatale. I’m really only interested in stories where she prevails in the end.

Which is not the vibe I get from your review unfortunately.

I’m trying really hard to reserve judgment on The Love Witch. Your analysis and the piece you linked to on The Wild Hunt Blog lead me to think I should see it despite my misgivings. That said, seeing the carefully researched vestments of my tradition’s clergy on the body of a murderous character, seeing the implements of my tradition’s rituals used to create a sense of menace about a sociopath makes me uneasy and tentatively angry at the filmmaker. Were Pagans not misrepresented and defamed enough before? Apparently. The Pagan community includes its fair share of problematic people. I’ve met a few. What surrounds such people in real life, and what seems to be absent in descriptions of the film, is a concerned wider Pagan community actively trying to mitigate damage and stop people who damage others. A well researched film that gives us a pagan sociopathic murderer but no Pagans of goodwill looks to me like it could turn out to be one more round of defamation. Thank you for calling my attention to this film. This time it’s not just curiosity — I have a responsibility to check this one out.