Fantasia 2016, Day 2: Some Monsterism (Guillermo del Toro press conference and master class, The Dark Side of the Moon, Creature Designers — The Frankenstein Complex, and Rupture)

Friday, July 15, began early for me. I headed down to Fantasia’s De Sève Theatre to watch a 2 PM press conference with the winner of this year’s Cheval Noir Award, Guillermo del Toro. I’d already decided that afterwards I’d head to the festival’s screening room and watch one of the movies I’d be unable to attend due to a scheduling conflict, a German suspense thriller called The Dark Side of the Moon. Then I’d go to the Hall Theatre to watch Creature Designers — The Frankenstein Complex, a documentary about the makers of movie monsters in the 1980s and 1990s. That was to be followed by a master class on monsters given by del Toro to the Creature Designers audience. I’d wrap up my night with Rupture, a suspense movie with science-fiction elements.

Friday, July 15, began early for me. I headed down to Fantasia’s De Sève Theatre to watch a 2 PM press conference with the winner of this year’s Cheval Noir Award, Guillermo del Toro. I’d already decided that afterwards I’d head to the festival’s screening room and watch one of the movies I’d be unable to attend due to a scheduling conflict, a German suspense thriller called The Dark Side of the Moon. Then I’d go to the Hall Theatre to watch Creature Designers — The Frankenstein Complex, a documentary about the makers of movie monsters in the 1980s and 1990s. That was to be followed by a master class on monsters given by del Toro to the Creature Designers audience. I’d wrap up my night with Rupture, a suspense movie with science-fiction elements.

You can watch the hour-long press conference with del Toro here. A few things struck me, then and also now as I look back in the light of hindsight and of other movies I’d see at Fantasia this year.

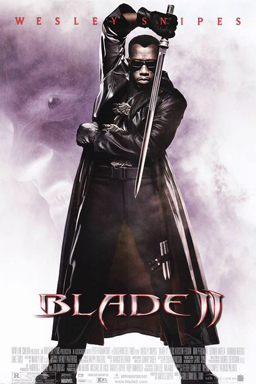

As del Toro recalled his start as “part of a monster-kit geekdom,” I found him remarkably and indeed touchingly open about his love for monsters. From his discussion of learning English by reading issues of Famous Monsters of Filmland with a dictionary, to his analysis of Frankenstein’s monster as a holy figure (and it’s worth noting that he never simply said “Frankenstein,” but always “Frankenstein’s monster”), del Toro emphasised the power and meaning of the monstrous and how the idea of the monster has inspired him and his filmmaking voice. He recalled making Blade 2 where he told star Wesley Snipes that he didn’t understand Blade or why Blade was killing vampires — Snipes should take care of Blade, and del Toro would handle everything else.

Del Toro made some strong points in a number of places about the importance of collaboration, reflecting that a model that looks spectacular on film may not be very impressive in real life. It’s a question of how the model is lit and shot, he said, just as a pet gecko lizard will die if stuck in a tin can but thrive if given a proper terrarium and food: the environment’s key. As a result, creature makers are “in a partnership with a cinematographer who may not understand it. … You depend on the kindness of strangers.” (He refused to say that CGI was better or worse than practical effects, saying that it’s more important to use the right technique for the situation, and that rather than CGI versus practical the distinction was between lazy and creative.) Similarly, he discussed his role on The Strain, the TV show based on a novel trilogy he wrote with Chuck Hogan; del Toro’s involved in the show but not the main decision-maker, and seemed fascinated by the way the dynamics of the show were different from the story he had envisioned. He remembered a conversation with Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy, in which Mignola had told him how weird it was to see another Hellboy from Mignola’s own. Del Toro said he hadn’t then understood what Mignola had meant, but understands it now.

Del Toro made some strong points in a number of places about the importance of collaboration, reflecting that a model that looks spectacular on film may not be very impressive in real life. It’s a question of how the model is lit and shot, he said, just as a pet gecko lizard will die if stuck in a tin can but thrive if given a proper terrarium and food: the environment’s key. As a result, creature makers are “in a partnership with a cinematographer who may not understand it. … You depend on the kindness of strangers.” (He refused to say that CGI was better or worse than practical effects, saying that it’s more important to use the right technique for the situation, and that rather than CGI versus practical the distinction was between lazy and creative.) Similarly, he discussed his role on The Strain, the TV show based on a novel trilogy he wrote with Chuck Hogan; del Toro’s involved in the show but not the main decision-maker, and seemed fascinated by the way the dynamics of the show were different from the story he had envisioned. He remembered a conversation with Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy, in which Mignola had told him how weird it was to see another Hellboy from Mignola’s own. Del Toro said he hadn’t then understood what Mignola had meant, but understands it now.

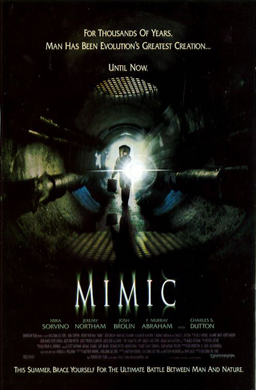

Similarly, del Toro was open about problems and how he as a director dealt with problems. Most notably in this context he spoke a fair amount about his 1997 film Mimic, where he was overridden on several key creative choices — he’d wanted to avoid a guns-and-explosions finale, and he’d wanted the main couple to be inter-racial so that at the end there wouldn’t be a set of all-white survivors but more of a microcosm of humanity. He was overridden on both counts (it’s not possible, in his judgement, to make a restored version of the existing film because what he wanted was never shot). Since 1997, he reflected, he’s come to appreciate the word ‘no,’ “a word that I knew but didn’t know how to use.” A young director, he observed, is viewed as something like a dancing bear, talented and loved but not taken seriously; “and then after that you have to become a bit of a motherfucker, and they respect that more.”

Similarly, del Toro was open about the problems and frustrations of his now-defunct attempt to make a film adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness: “Imagine that you had a horrible miscarriage that left a lot of scars and you’re still dangling a piece of placenta.” It was a very difficult process, he said, starting with getting the rights and going on for a decade and half including extensive design work and 700 storyboards. “It would break your heart. It really was a great monster movie and a great movie.” James Cameron was set to produce and Tom Cruise had agreed to star, and then the studio said no.

Similarly, del Toro was open about the problems and frustrations of his now-defunct attempt to make a film adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness: “Imagine that you had a horrible miscarriage that left a lot of scars and you’re still dangling a piece of placenta.” It was a very difficult process, he said, starting with getting the rights and going on for a decade and half including extensive design work and 700 storyboards. “It would break your heart. It really was a great monster movie and a great movie.” James Cameron was set to produce and Tom Cruise had agreed to star, and then the studio said no.

Still, del Toro said, for all the pain the process can cause you need to bring your personal touch to the films you do: “I don’t do any movie that I wouldn’t be willing to die for,” he said, noting the time and effort involved in making films. “[W]hen you take [on] a movie, you’re accepting that you’re going to disappear from your family’s life [for] three years, basically.” He’s turned down movies he didn’t believe in, such as The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. (“I’m a lapsed Catholic. I’m not interested in seeing the fucking lion resurrect. So I said, no, I don’t want the lion to resurrect and you’re not going to like that.”)

He spoke extensively on the importance of helping out new talent, especially new talent in genre, and on the importance of genre as a whole: “The thing that I love about our genre is that we truly love it. We are not here because it’s prestigious or chic, we’re not here to be seen, we’re not here because it gives us cachet, we’re here because we’re fucking nuts. We are truly in love with a thing that is for a lot of people unlovable. Fantasy in general, you can say sci-fi , horror, whatever you want, fantasy in general is frowned upon, and looked down [on] as something not only minor but actually in some instances despicable. But we know it’s not! And it’s pure fucking love.” The horror genre, he said, is an important motor of human imagination and human stories: “I believe wholeheartedly that you can actually talk about real issues more clearly with a non-real context.” For him the Fantasia festival has a special importance as a result. Fantasia and similar festivals are “places of true worship … this is a shrine. This is where the faithful come to pray. So that’s why I’m here.”

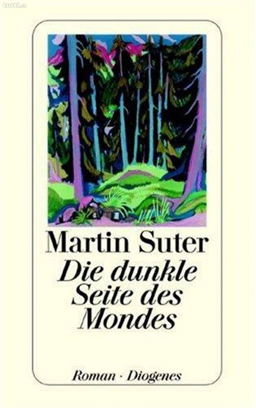

It was an inspiring discussion, and when I went from there to watch a movie at the festival’s screening room I was pondering questions of real and unreal stories, and questions of the human and the inhuman. I therefore sat down with The Dark Side of the Moon (Die dunkle Seite des Mondes), which looked as thought it would speak to me about those things. Directed by Stephan Rick from a novel by Martin Suter, written by Rick and Catharina Junk with a screenplay by David Marconi, it hints at the myth of the werewolf while downplaying the supernatural. The result’s an intriguing examination of what separates human and beast.

It was an inspiring discussion, and when I went from there to watch a movie at the festival’s screening room I was pondering questions of real and unreal stories, and questions of the human and the inhuman. I therefore sat down with The Dark Side of the Moon (Die dunkle Seite des Mondes), which looked as thought it would speak to me about those things. Directed by Stephan Rick from a novel by Martin Suter, written by Rick and Catharina Junk with a screenplay by David Marconi, it hints at the myth of the werewolf while downplaying the supernatural. The result’s an intriguing examination of what separates human and beast.

Urs Blank (Moritz Bleibtreu) is a successful lawyer working for a big German pharmaceutical company who masterminds mergers and takeovers. After a particularly cutthroat acquisition, which leads the former head of the acquired medical company to commit suicide in front of Blank, Blank’s boss Pius Ott (Jürgen Prochnow) puts Blank in charge of an even bigger merger with a British company. But Blank’s acting strange, spending time alone in the woods and breaking up with his wife Evelyn (Dois Schretzmayer) to pursue a relationship with a younger and politically radical woman, Lucille (Nora von Waldstätten). And he’s begun to suffer from unpredictable fits of rage. Has he been affected by the psychedelic mushrooms Lucille and her friends fed him? Or is a deeper conspiracy afoot? Is Blank in a race towards an early grave?

The plot provides the backbone of a brooding yet quickly-paced film that interrogates the distinction between supposedly civilized society and the inhuman wilderness. It’s extremely tightly-written and edited, moving along quickly and telling its tale in a lean 98 minutes. The performances are very strong, especially that of Bleibtreu, who is hardly ever off screen; this is thoroughly Blank’s story, and Bleibtreu crafts a convincing portrait of a man frequently on the run and being pushed further and further from a world of time and money into savagery by demons of unknown origin.

The plot provides the backbone of a brooding yet quickly-paced film that interrogates the distinction between supposedly civilized society and the inhuman wilderness. It’s extremely tightly-written and edited, moving along quickly and telling its tale in a lean 98 minutes. The performances are very strong, especially that of Bleibtreu, who is hardly ever off screen; this is thoroughly Blank’s story, and Bleibtreu crafts a convincing portrait of a man frequently on the run and being pushed further and further from a world of time and money into savagery by demons of unknown origin.

There are elements here that feel familiar: evil corporations, conspiracy, rituals that unlock the true self through a night journey in the underworld. On the other hand, the movie invests these common plot manoeuvres with a sense of unstated significance: it’s as though they happen in the background, shadows of Blank’s self, while what matters is the personal emotional journey Blank undergoes. On that level the film works through Rick’s visual sense. We see long shots with a forest in the foreground and gleaming office towers in the background, and the images insist on the juxtaposition if not the blurring of the human and the wild. Colour emphasises the meaning of place, cool and glittering in the city, the forest rich yet subdued.

Certainly the film moves away from simple plot explanation for Blank’s wildness. Instead there’s a kind of Romanticism out of Schlegel or Tieck. One man against the depths of his own psyche; a fascination with subjective mental states of high emotion, with hallucinatory states, with what is not conscious; a story that takes place against the backdrop of the wild woods of a fairy-tale or märchen. Blank acquires some extra dimensions through this resonance — his violent rejection of a friend’s birthday wish for things to remain ever the same could, in this reading, be taken not just as the reaction of a man deeply dissatisfied with his own life but also as that of a kind of Faustian striver — but at the same time close observation of an individual means the other characters are reduced to near-ciphers. Prochnow in particular is underused, creating the sense of a film without an antagonist.

Certainly the film moves away from simple plot explanation for Blank’s wildness. Instead there’s a kind of Romanticism out of Schlegel or Tieck. One man against the depths of his own psyche; a fascination with subjective mental states of high emotion, with hallucinatory states, with what is not conscious; a story that takes place against the backdrop of the wild woods of a fairy-tale or märchen. Blank acquires some extra dimensions through this resonance — his violent rejection of a friend’s birthday wish for things to remain ever the same could, in this reading, be taken not just as the reaction of a man deeply dissatisfied with his own life but also as that of a kind of Faustian striver — but at the same time close observation of an individual means the other characters are reduced to near-ciphers. Prochnow in particular is underused, creating the sense of a film without an antagonist.

The women in the film fare a little better, especially Evelyn, who emerges strongly as a character in the second half of the story. At the same time, there’s a sense of cliché to the whole endeavour: the older wife, the young girlfriend, the middle-aged man briefly reinvigorated by an affair. What The Dark Side of the Moon does that is less common is tie the story of reawakened sexuality to a reawakened urge to violence. And at that it’s clever, in that it doesn’t turn Blank into an unstoppable berserker in his use of violence: consciously or not, the man picks his spots, using force where he can overpower his opponent, and in other circumstances intimidation with whatever comes to hand in order to enforce his dominance. His anger is a kind of sadism, reinforcing a hierarchy with himself at the top rather than really challenging society.

Still, what is distinctive in the film is the way it mixes the thriller form with a sense of ritual unlocking of the psyche. Little is shown, but a cave in the woods becomes a crucial location, a place Blank loses and finds himself. It’s a place where worlds come together, a place of transformation. A place where chthonic powers emerge, and who knows which is which and who is who: if the film hints at the image of the werewolf, with Blank’s rages and the shots of the deep woods and the recurring image of a big black wolf, it avoids any direct reference to physical transformation to insist that the monster is already within us. “The lunatic is in my head,” as the lyric has it. Or: man is wolf to man.

Still, what is distinctive in the film is the way it mixes the thriller form with a sense of ritual unlocking of the psyche. Little is shown, but a cave in the woods becomes a crucial location, a place Blank loses and finds himself. It’s a place where worlds come together, a place of transformation. A place where chthonic powers emerge, and who knows which is which and who is who: if the film hints at the image of the werewolf, with Blank’s rages and the shots of the deep woods and the recurring image of a big black wolf, it avoids any direct reference to physical transformation to insist that the monster is already within us. “The lunatic is in my head,” as the lyric has it. Or: man is wolf to man.

At the end of the film Blank makes a decision that seems to insist on his humanity, his sense of morality. He turns away from an act of violence. And yet that decision’s undercut by the actions of another character, raising a separate moral conundrum. The point may be that seizing at morality is itself a human act. But it also calls into question what is most human. When Faust ceases to strive, he’s damned.

What strikes me most about the film in the end is the way in which it undercuts any easy hierarchy of society and nature. Corporate barbarity is more rapacious than any wolf. On the other hand, deaths of animals in this film are given weight and meaning, frequently more so than human deaths; the murder of the non-human marks a crossing of boundaries in a way that the murder of the merely human does not. So what remains with me from The Dark Side of the Moon is not the competent thriller plot but the sense of worlds, or indeed of moons, revolving around that plot with ever-unseen sides. Which is to say there is a sense of psychological depth that nearly eclipses the narrative. If the film had been able to bring that out further it might have been brilliant. As it is, I think it’s a well-made movie with a powerful subtext, well worth watching.

From the screening room I went to a packed Hall Theatre to watch Creature Designers — The Frankenstein Complex. It’s a documentary about the makers of film monsters, particularly those in the 1980s and 1990s, and the showing would be followed by a master class on monsters led by Guillermo del Toro, one of the interviewees in the film. Fantasia’s two Directors of International Programming, Tony Timpone and Mitch Davis (the latter of whom is also one of the festival’s two General Directors) introduced him before the film started, prompting a standing ovation in the Hall, the larger of Fantasia’s two main theatres, and a chant of “Guy-yer-mo! Guy-yer-mo!” Presented with the festival’s Cheval Noir award, del Toro was choked up, and assured the crowd that the film we were about to see was “made by fans for fans.”

From the screening room I went to a packed Hall Theatre to watch Creature Designers — The Frankenstein Complex. It’s a documentary about the makers of film monsters, particularly those in the 1980s and 1990s, and the showing would be followed by a master class on monsters led by Guillermo del Toro, one of the interviewees in the film. Fantasia’s two Directors of International Programming, Tony Timpone and Mitch Davis (the latter of whom is also one of the festival’s two General Directors) introduced him before the film started, prompting a standing ovation in the Hall, the larger of Fantasia’s two main theatres, and a chant of “Guy-yer-mo! Guy-yer-mo!” Presented with the festival’s Cheval Noir award, del Toro was choked up, and assured the crowd that the film we were about to see was “made by fans for fans.”

Directed by Gilles Penso and Alexandre Poncet, Creature Designers is built around a series of interviews with directors, designers, and visual effects wizards. It takes a relatively brief look at the narrative meaning of monsters — what their use is and what they reflect about us — then considers what makes a good monster before settling into a history of monsters in film, focussing on a period from the 1970s through the 1990s. That’s roughly the time when “special make-up effects” became a common credit through to the point when computer imagery began to emerge as a dominant effects technique. This was an era when some of the most famous of film monsters were first put on screen, and, according to many interviewees, a time when effects makers were viewed in some quarters like rock stars. Or, from another angle, a time when those effects makers built on their predecessors to develop their craft into an art, which itself merged with other arts into the gesamtkunstwerk of film.

That’s something of a maximal statement. Creature Designers does support it, though there is a feeling of a lack of focus to the film. It’s 107 minutes, but feels longer. I thought that the earlier sections, describing the meaning and design of monsters, should have either been expanded, cut, or (ideally) integrated differently into the film’s chronology. So much of the film is given over to history that these sections feel, in retrospect, beside the point. That’s a harsh thing to say about some fascinating material — particularly powerful moments are John Howe remarking on the way a monster forces us to recognise otherness, and Cristophe Gans discussing the monster as a mirror for the human — but while they justify the use of the history that follows I’m not sure the history needs justifying. A general documentary on monsters or film monsters could use these comments, but they’re beside the point in a history of film monsters.

That’s something of a maximal statement. Creature Designers does support it, though there is a feeling of a lack of focus to the film. It’s 107 minutes, but feels longer. I thought that the earlier sections, describing the meaning and design of monsters, should have either been expanded, cut, or (ideally) integrated differently into the film’s chronology. So much of the film is given over to history that these sections feel, in retrospect, beside the point. That’s a harsh thing to say about some fascinating material — particularly powerful moments are John Howe remarking on the way a monster forces us to recognise otherness, and Cristophe Gans discussing the monster as a mirror for the human — but while they justify the use of the history that follows I’m not sure the history needs justifying. A general documentary on monsters or film monsters could use these comments, but they’re beside the point in a history of film monsters.

Still, the interviews that make up the film are very strong. The subjects are clearly intelligent, and the filmmakers give us time with almost every crucial voice in monster-making of the late twentieth century. This does mean a preponderance of white and (almost entirely) male voices, especially notable given Howe’s comments on otherness and Steve Johnson’s statement that making a film monster is the closest he as a man feels he can come to creating life.

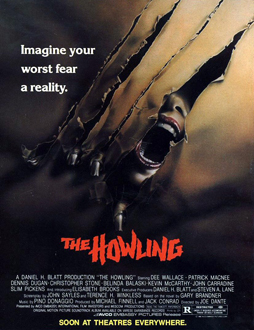

Of course, in the context of movie monsters, creating monstrous life has a referent of its own. Frankenstein’s monster is often evoked in this film, far more so than any other early movie monster (Universal’s Wolfman is the only other one that even comes close, and that’s mostly in the context of a discussion of new techniques developed for The Howling and An American Werewolf in London). There is a sense of history in the film, then, a sense of creators building on a tradition, but also a sense of a tradition being developed to a peak by people pushing the boundaries of what was technically achievable. There aren’t too many deep practical discussions of how effects were done, at least I suspect nothing that would surprise someone with a keen interest in the subject, but Creature Designers does establish a sense of how one artisan or film would influence another and how the field developed over time.

Of course, in the context of movie monsters, creating monstrous life has a referent of its own. Frankenstein’s monster is often evoked in this film, far more so than any other early movie monster (Universal’s Wolfman is the only other one that even comes close, and that’s mostly in the context of a discussion of new techniques developed for The Howling and An American Werewolf in London). There is a sense of history in the film, then, a sense of creators building on a tradition, but also a sense of a tradition being developed to a peak by people pushing the boundaries of what was technically achievable. There aren’t too many deep practical discussions of how effects were done, at least I suspect nothing that would surprise someone with a keen interest in the subject, but Creature Designers does establish a sense of how one artisan or film would influence another and how the field developed over time.

The tradition, of course, received a sharp shock in the 1990s when computers become more prominent. There is much discussion of Jurassic Park and The Abyss and the feelings of longtime industry veterans at the new tools. But the film also argues convincingly that this is a story and a tradition still ongoing. More contemporary film effects than one would think are practical. And new developments in practical technologies are still emerging: new materials are being created, new kinds of motors invented. Challenges are still being met with unexpected solutions. What is different, argues the film, is the lack of respect the special effects creators are given by the industry. The prestige they had two or three decades ago, and the common acknowledgement that these were people with individual and valuable skills, are no longer so easily granted. And with that lack of respect for their art has come tighter budgets and tighter schedules, as the work they do becomes almost taken for granted.

The tradition, of course, received a sharp shock in the 1990s when computers become more prominent. There is much discussion of Jurassic Park and The Abyss and the feelings of longtime industry veterans at the new tools. But the film also argues convincingly that this is a story and a tradition still ongoing. More contemporary film effects than one would think are practical. And new developments in practical technologies are still emerging: new materials are being created, new kinds of motors invented. Challenges are still being met with unexpected solutions. What is different, argues the film, is the lack of respect the special effects creators are given by the industry. The prestige they had two or three decades ago, and the common acknowledgement that these were people with individual and valuable skills, are no longer so easily granted. And with that lack of respect for their art has come tighter budgets and tighter schedules, as the work they do becomes almost taken for granted.

Creature Designers might have been designed as a rebuke to that indifference, arguing strongly that the monster makers are artists with visions of their own. And this is where the discussion of monsters at the start of the film does have value, and why I’d rather see it integrated more smoothly into the film than jettisoned. The value of the monster as symbol ought to transition easily to the significance of what an artist does with that symbol, and I feel that transition is if not missing then at least not as smooth as it ought to be. One can argue that the interview clips tend not to focus on individual film narratives, or the role the characters devised by the effects creators play in those stories. But either way, I feel there’s a step missing or half-missing.

Creature Designers might have been designed as a rebuke to that indifference, arguing strongly that the monster makers are artists with visions of their own. And this is where the discussion of monsters at the start of the film does have value, and why I’d rather see it integrated more smoothly into the film than jettisoned. The value of the monster as symbol ought to transition easily to the significance of what an artist does with that symbol, and I feel that transition is if not missing then at least not as smooth as it ought to be. One can argue that the interview clips tend not to focus on individual film narratives, or the role the characters devised by the effects creators play in those stories. But either way, I feel there’s a step missing or half-missing.

Still, in other respects the film does a good job of maintaining its focus. It’s interested in more than just make-up effects, though that is a huge part of its subject. It also discusses models, and occasionally puppetry and even animation. With those latter two fields in particular it displays some fine judgement, explaining just what aspects of these approaches are relevant to its subject without going too far into what are distinct cinematic realms. The movie sticks to the monsters, and to the making of character and life. It’s a conceptual boundary, and one that works.

Visually, the movie suffers a little from the occasional lack of a clip that would have been useful to illustrate a point. The CG water creature in The Abyss, which clearly established the potential of computers, is notable by its absence. The movie illustrates many of the best film monsters with shots of highly-detailed models, an interesting choice that seems to insist on the existence of the creatures outside of the films for which they were birthed. They are abstracted from their stories, viewed from new angles, given new reality. But then, we’re also given many behind-the-scenes shots and process shots, demonstrating their gestation.

I came away from Creature Designers struck by the fact that virtually none of the movies mentioned in the documentary are widely regarded as actively bad. Many movies that are classics of effects work are not overall cinematic classics — films like The Abyss or Legend or probably even John Carpenter’s The Thing are more notable in their genres than as great films top-to-bottom. On the other hand, films like Alien or The Exorcist have a high level of general critical respect. But only a couple of more-or-less-deliberately campy films in Creature Designers could be qualified as outright poor (Killer Klowns From Outer Space and Critters, I think, and I don’t know what else). Even those might be well-regarded as camp. The point is that just as a remarkable soundtrack or human acting performance can elevate a film, perhaps so too can an acting performance from make-up work or a special effect. It’s another useful point to draw from a useful and frequently fascinating film. I wish Creature Designers had been organised a little differently, but it’s very strong in its depiction of a film tradition and of the fascination of the monstrous.

I came away from Creature Designers struck by the fact that virtually none of the movies mentioned in the documentary are widely regarded as actively bad. Many movies that are classics of effects work are not overall cinematic classics — films like The Abyss or Legend or probably even John Carpenter’s The Thing are more notable in their genres than as great films top-to-bottom. On the other hand, films like Alien or The Exorcist have a high level of general critical respect. But only a couple of more-or-less-deliberately campy films in Creature Designers could be qualified as outright poor (Killer Klowns From Outer Space and Critters, I think, and I don’t know what else). Even those might be well-regarded as camp. The point is that just as a remarkable soundtrack or human acting performance can elevate a film, perhaps so too can an acting performance from make-up work or a special effect. It’s another useful point to draw from a useful and frequently fascinating film. I wish Creature Designers had been organised a little differently, but it’s very strong in its depiction of a film tradition and of the fascination of the monstrous.

After the screening del Toro came out to give his master class on monsters, which largely consisted of taking questions from Timpone and the audience. There struck me as being little difference in his manner between the press conference in the afternoon and the question-and-answer in the Hall in front of about twenty times as many people. Again he spoke about his childhood; and here he observed that we become who we are, drawn to specific images and themes, before adulthood — in his case, before puberty.

The entire master class is online, but again I’ll highlight a few points in particular. Perhaps del Toro’s most practical advice in monster designing came near the start, when he discussed the creation of the visual identity of a monster. He advised starting with the silhouette and not the details of the design, something he learned from animation. Create the thing’s personality, but do not begin by imagining it with a furrowed brow. Don’t start with it angry. Give it somewhere to go emotionally, and the ability to change. He cited the Reapers in Blade 2 as an example, monsters that only revealed their true nature a third of the way into the film: “[W]hen we were testing that movie the first time the audience levitated” at that point, he remembered. Colour is important, and again he recommended establishing a general colour scheme rather than colouring in every detail. And always, he said, in designing a creature have a reference in nature: “Nature has designed already the craziest monsters of all time. You’re not gonna beat that.”

On other subjects I was struck by his observation of the importance for a director of knowing everything about everything, of magpie-like collecting facts; of gathering visuals from all sources as writers gather words. Of milking the world for images. And, later, of how one learns by doing different things — hence his work directing a video game. It went with an insistence on the individuality of different media, of how movies are not games just as comics are not storyboards. And again here he spoke about individuality in filmmaking, how individual directors have specific tics or habits — for example, the way the Coen brothers often use the plot device of a MacGuffin that’s forgotten by the end of a movie. (He also said that their recent Hail, Caesar! was one of their greatest movies.)

On other subjects I was struck by his observation of the importance for a director of knowing everything about everything, of magpie-like collecting facts; of gathering visuals from all sources as writers gather words. Of milking the world for images. And, later, of how one learns by doing different things — hence his work directing a video game. It went with an insistence on the individuality of different media, of how movies are not games just as comics are not storyboards. And again here he spoke about individuality in filmmaking, how individual directors have specific tics or habits — for example, the way the Coen brothers often use the plot device of a MacGuffin that’s forgotten by the end of a movie. (He also said that their recent Hail, Caesar! was one of their greatest movies.)

Asked about Catholic themes in horror, del Toro said that while he could not honestly tell audiences that the devil was evil and the Church was good, because he himself did not believe these things, it was easy to use the Judeo-Christian idea of good and evil to scare people. He believes that everyone has evil and good within themselves and that “the moment you displace your damnation or your salvation to a power outside of you you’re fucked.” Generally he said that he felt horror movies, like fairy tales, can be divided into two groups: pro-structure, and “fuck the man” stories. He feels he himself is anti-structure as a storyteller; he recognises good work has been done in telling pro-structure stories, but couldn’t make one himself. Even in Pacific Rim he felt it was important that humanity’s saviours be a ragtag group, that there be every nationality, that the leader be black, that “an Asian girl kick as much ass as the guys.” Later, in response to a questioner expressing nervousness about the rise of Donald Trump and the current American political situation, del Toro said that the first thing to do is be a good citizen oneself and take care of one’s own house, then work outward from there — but also that every choice is political and that storytelling choices are political choices.

Returning to Creature Designers, he was asked if an era is passing in moviemaking and special effects. He answered that the film was like a film about vaudevillians, an era that has passed but which, as is the case with vaudeville or grand guignol, will also live so long as some practitioners keep it alive even in the face of faith and reason. As he had earlier in the day, he talked about the use of CGI, how it could be married to practical effects and how it has limitations. He noted he liked building sets, such as the house in Crimson Peak, as a way of creating a sense of character and place as well as a help for actors. He uses digital effects as a last resource when he can’t do practical in-camera effects; any other way, he said, is “like shooting someone before arguing.” Making a film, he said, is a balance between control and accident, but computer animation is all control pretending to be accident. There are no lucky missteps or useful errors in CGI; therefore performances are not as full.

Returning to Creature Designers, he was asked if an era is passing in moviemaking and special effects. He answered that the film was like a film about vaudevillians, an era that has passed but which, as is the case with vaudeville or grand guignol, will also live so long as some practitioners keep it alive even in the face of faith and reason. As he had earlier in the day, he talked about the use of CGI, how it could be married to practical effects and how it has limitations. He noted he liked building sets, such as the house in Crimson Peak, as a way of creating a sense of character and place as well as a help for actors. He uses digital effects as a last resource when he can’t do practical in-camera effects; any other way, he said, is “like shooting someone before arguing.” Making a film, he said, is a balance between control and accident, but computer animation is all control pretending to be accident. There are no lucky missteps or useful errors in CGI; therefore performances are not as full.

In some cases, del Toro said, when his desire for an effect ran into budget-conscious executives he would offer to pay for the effect himself. It was important for him, he said, to love the movies he made, and in fact whether other people loved them was secondary. There are two choices in life, he said, be perfect or learn where you fucked up. Success is fucking up on your own terms and learning from it; if someone else fucks up your movie, you can’t learn. At the same time, movies are “a hostage negotiation with compromises.” Asked if it’s easier to write for film with contemporary effects techniques, del Toro said that you never get everything you want as a director, whatever your budget. The important thing is to win the war, not every battle. He distinguished between approaching a story as a traveller as opposed to a tourist, rambling about and getting a little lost as opposed to following an itemised itinerary. How do you pick which story to tell? It varies, and sometimes you don’t know: “It’s your duty not to know, I think.” He once started writing a story about a vacation he’d had with his father, got twenty pages in while weeping all the way, then was never able to write more of it. Writing, he said, is like dominos; but you don’t know what domino will trigger what fall. In the end he recommended going with what scares you: “In order to find your voice you go to the place where it hurts.”

On the other hand, when asked about how he mixes horror and humour, he cited older films that had come to seem funny, and said there was a need to go close to ridicule. If you don’t risk that, he said, the image doesn’t have power. He felt that balancing both comedy and horror in the way of a Joe Dante was something he himself couldn’t do, that he only used odd moments of humour. Then, when asked if Lovecraft was difficult to adapt to film because he was too abstract, del Toro said Lovecraft’s horror worked by making you “feel those blanks” in his adjectives. “Literature is complicit with you,” he said. “Film is specific … you cannot imagine any more [than what’s on screen].” Like humour, he went on, horror is very subjective. A horror film turns off a certain percentage of audience not on the same wavelength as the story. Lovecraft, like Bradbury, has a specific voice that looks easy to imitate but isn’t. Which is why many people focus on the surface details. Del Toro said he loves movies that come from a deep care for and understanding of their source, not mere imitation. He cited Alien as an example, which he said was a version of At the Mountains of Madness: explorers, the ruins of an advanced civilization, dead masters of the civilization, a terrifying servitor race still alive. If his own version of At the Mountains of Madness isn’t made in next 10 years, he said, he’ll publish a book of the script accompanied by concept art.

On the other hand, when asked about how he mixes horror and humour, he cited older films that had come to seem funny, and said there was a need to go close to ridicule. If you don’t risk that, he said, the image doesn’t have power. He felt that balancing both comedy and horror in the way of a Joe Dante was something he himself couldn’t do, that he only used odd moments of humour. Then, when asked if Lovecraft was difficult to adapt to film because he was too abstract, del Toro said Lovecraft’s horror worked by making you “feel those blanks” in his adjectives. “Literature is complicit with you,” he said. “Film is specific … you cannot imagine any more [than what’s on screen].” Like humour, he went on, horror is very subjective. A horror film turns off a certain percentage of audience not on the same wavelength as the story. Lovecraft, like Bradbury, has a specific voice that looks easy to imitate but isn’t. Which is why many people focus on the surface details. Del Toro said he loves movies that come from a deep care for and understanding of their source, not mere imitation. He cited Alien as an example, which he said was a version of At the Mountains of Madness: explorers, the ruins of an advanced civilization, dead masters of the civilization, a terrifying servitor race still alive. If his own version of At the Mountains of Madness isn’t made in next 10 years, he said, he’ll publish a book of the script accompanied by concept art.

I liked the idea of following a documentary and master class about monsters with a horror movie, and following the question-and-answer I returned to the Hall to watch Rupture. Directed by Stephen Shainberg, written by Shainberg and Brian Nelson, the movie follows a woman named Renee (Noomi Rapace) who is kidnapped and taken to a distant facility. Her kidnappers are experienced and efficient, operating according to a system Renee can’t understand, apparently in an attempt to extract information she doesn’t know. Renee sees other victims, subjects of what seems to be psychological and physical experimentation, and struggles to free herself, trigging a suspenseful cat-and-mouse chase. The nightmare builds as Renee struggles to understand what her captors mean by strange references to a “rupture” — and the nature of the world in which she has become implicated.

The film begins with Renee and her son going about their lives, seen through surveillance cameras hidden in their house. That builds a sense of paranoia which only grows. In passing we get a mention of manmade environmental degradation, setting up themes that come into play much later: the limitation of human intellect, the clumsiness of technology and society. The pace starts slow and builds in intensity and in atmosphere. There’s a sense in which the movie really comes alive once Renee’s been abducted and taken to the mysterious facility that serves her captors as a base: the place is colourful yet decayed, full of character and threat. Triple-bolted doors lock with a repetitive three-strike beat. Hallways are dark and debris is scattered everywhere. There’s an aesthetic of industrial grit in every square centimetre, abandoned corridors sprawling in every direction, the whole far too large for the number of people within it.

The film begins with Renee and her son going about their lives, seen through surveillance cameras hidden in their house. That builds a sense of paranoia which only grows. In passing we get a mention of manmade environmental degradation, setting up themes that come into play much later: the limitation of human intellect, the clumsiness of technology and society. The pace starts slow and builds in intensity and in atmosphere. There’s a sense in which the movie really comes alive once Renee’s been abducted and taken to the mysterious facility that serves her captors as a base: the place is colourful yet decayed, full of character and threat. Triple-bolted doors lock with a repetitive three-strike beat. Hallways are dark and debris is scattered everywhere. There’s an aesthetic of industrial grit in every square centimetre, abandoned corridors sprawling in every direction, the whole far too large for the number of people within it.

Struggling to be free and escape this place, Renee emerges as an engaging character, resourceful and courageous. One wonders at first about how easily she overcomes her fear of what’s happened to her — but then in many ways the movie is about fear and the use of fear, about fear as a test or crucible. There are contrivances here, yes, but not necessarily the ones we think at first, and by the end the movie has done a good job of questioning even the contrivances it has put forward. We have come to understand by then how theatrical the movie is. How conscious it is of form and the use of genre: the emotional terrain of horror and what horror can be used for. Horror as a means of transformation: “When you take the fear into your bones it changes the shape of you,” we are told, and the glance at body horror becomes briefly yet thoroughly realised.

Without wanting to give away too much of the plot I would say that this is a story about transcendence. Specifically about transcending oneself, about the devising of a rupture with one’s past, and with the world, and even with the human body. It is possible to read the film as something like an initiation into a mystery religion, a journey through fear to revelatory truth. If so, it’s a story that emphasises the trauma and distance of revelation from everyday life. It is, after all, named Rupture, and if that reminds us of Rapture it also implies trauma — a forcible break.

Images of things rupturing could be said to recur in the movie, as Renee breaks through one barrier after another trying to become free. Another way to say it is that images of being bound or locked in dominate the movie, emphasised with the echoing of the triple-bolted doors. This is a struggle for freedom that questions what freedom means and, perhaps, whether it is possible to understand what binds us while we are still bound. But freedom is a means to a different emotional end here, a contrast against which claustrophobia and suspense work.

Images of things rupturing could be said to recur in the movie, as Renee breaks through one barrier after another trying to become free. Another way to say it is that images of being bound or locked in dominate the movie, emphasised with the echoing of the triple-bolted doors. This is a struggle for freedom that questions what freedom means and, perhaps, whether it is possible to understand what binds us while we are still bound. But freedom is a means to a different emotional end here, a contrast against which claustrophobia and suspense work.

Perhaps inevitably the depiction of what lies beyond a moment of transcendence is lacking. For all the mystical overtones this is a profoundly science-fictional movie, about plans and clever improvisations and a protagonist discovering her own competence as much as it is about advanced technology. From a certain point of view the explanation of events put forward is underplayed, if not weak. There’s just enough information for it to work, but much left to the viewer’s imagination. It is possible to extrapolate from what we’ve seen, I think, but this is not be mistaken for hard science fiction. I would say that it’s a horror-suspense story which uses science-fictional terminology to tell an ambiguous story about what it means to become other than what one was.

And elements of the ending do feel inconclusive to me. The film seems to stop just when battle-lines are clearly drawn, with a conflict finally revealed after the rest of the film has led up to it. I find myself wanting to know what comes next. One might argue that Renee’s experiences up to the point of conclusion have led her to a specific path, perhaps to overcome her own overcoming, but then that also is ambiguous. With a closing monologue that could be read as villainous or blustery, there is finally too much ambiguity, and so that last note seems ill-chosen: the story has to end, and it is being forced to end here, but it’s too easy to doubt, too uncertain.

And elements of the ending do feel inconclusive to me. The film seems to stop just when battle-lines are clearly drawn, with a conflict finally revealed after the rest of the film has led up to it. I find myself wanting to know what comes next. One might argue that Renee’s experiences up to the point of conclusion have led her to a specific path, perhaps to overcome her own overcoming, but then that also is ambiguous. With a closing monologue that could be read as villainous or blustery, there is finally too much ambiguity, and so that last note seems ill-chosen: the story has to end, and it is being forced to end here, but it’s too easy to doubt, too uncertain.

Still, overall the film’s gripping. Rupture is a movie about the cost of self-overcoming, I think, and it arrives at this theme in careful stages. It’s well-shot and well-paced. Rapace is highly effective in an absolutely central role, onscreen almost constantly and carrying the film as her character is pushed to strange places. The sense of isolation and paranoia that dominates much of the film is compelling, as is the slowly increasing sense of surrealism. It’s an unconventional approach to its subject, and one that demands some thought, but an effective story.

A question-and-answer session with director Steven Shainberg and producer Andrew Lazar and cinematographer Karim Hussain followed (the description that follows come from handwritten notes). Shainberg spoke about the origin of the project, after he saw Paranormal Activity and disliked it; and then described how the idea of a found-footage film was dropped as it became clear the structure of a fake documentary would be too limiting. Asked about funding he began by saying “It’s impossible to get any movie made, ever.” Every movie, he said, is a miracle. In this case his producer, Lazar, found generous financiers; the way you get a movie made, he concluded, is to have an absolutely relentless producer. Lazar said that the trick to getting an unusual movie made is to pretend it’s more ordinary and pitch it as an ordinary film.

A question-and-answer session with director Steven Shainberg and producer Andrew Lazar and cinematographer Karim Hussain followed (the description that follows come from handwritten notes). Shainberg spoke about the origin of the project, after he saw Paranormal Activity and disliked it; and then described how the idea of a found-footage film was dropped as it became clear the structure of a fake documentary would be too limiting. Asked about funding he began by saying “It’s impossible to get any movie made, ever.” Every movie, he said, is a miracle. In this case his producer, Lazar, found generous financiers; the way you get a movie made, he concluded, is to have an absolutely relentless producer. Lazar said that the trick to getting an unusual movie made is to pretend it’s more ordinary and pitch it as an ordinary film.

Asked about the movie’s colour scheme, Hussain said he had read the script, and worked to understand it and make the lighting and visuals part of the theme of the movie, using lights as a character in the film. To an observation that it had been a while since Shainberg had made a movie — ten years since Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus — Shainberg replied that this movie reminded him that he could make a movie. To another question, he discussed the performance style of the supporting cast in the film, and how the actors had to convey in their performances a specific experience the script suggested they had been through. But there was little time for rehearsal: “When you make a low-budget movie,” he said, “you don’t have time to do shit.” He was able to talk through scenes on the phone with Rapace in hour-long phone conversations before beginning production, which helped.

A question from the audience about a design element in the film led Shainberg to state that everything in the film was very consciously chosen, and much was imagined that did not make it into the movie. So he had his own answer for who made some of the things we see in the film. Similarly, wallpaper in the film that seemed to evoke The Shining was consciously chosen to evoke a loss of the sense of time (Shainberg also said that every human being on Earth should watch The Shining at least once a week). Other cinematic points of reference for the film Shainberg mentioned included Polanski’s Repulsion, while Hussain spoke more generally about his intense preparation for creating the film’s visuals.

A question from the audience about a design element in the film led Shainberg to state that everything in the film was very consciously chosen, and much was imagined that did not make it into the movie. So he had his own answer for who made some of the things we see in the film. Similarly, wallpaper in the film that seemed to evoke The Shining was consciously chosen to evoke a loss of the sense of time (Shainberg also said that every human being on Earth should watch The Shining at least once a week). Other cinematic points of reference for the film Shainberg mentioned included Polanski’s Repulsion, while Hussain spoke more generally about his intense preparation for creating the film’s visuals.

Asked about the way Renee’s adversaries touched people in slightly unusual and slightly disconcerting ways, Shainberg noted that he doesn’t himself like to be touched by people he doesn’t know (a hardship on set, he said, where people massage each other to relieve tension). He put that discomfort in the movie: “At a certain point you gotta make a movie for yourself, or what’ve you got?” Asked about the recurring sound of the triple bolts on the doors, Shainberg said that he had the general idea from the beginning and found the specific form in the process of cutting the movie.

Finally, asked about the ending, Lazar said that there had been some debate among the filmmakers. Two endings had been shot, involving different final choices by Renee. Shainberg said it was a questioning of working through the metaphor of religious experience, and how complete the division was between Renee’s final state and her old life. He wanted to avoid the simplistic, and a final choice that he regarded as more “genre.” He likes the ending, feeling it raises questions rather than answers them.

That ended the night, and I began walking home thinking over what I’d seen that day. I’d heard Guillermo del Toro present a vision of horror and horror filmmaking and how those things worked; and I’d seen two examples of what he’d been talking about as well as a documentary about the genre. It struck me that both the fiction films I’d seen had been anti-structure, insisting on an individual’s journey and the individual exploration of the psyche; in these movies social structures were hostile or untrustworthy. But it also struck me that these films were more reserved abut embracing genre than del Toro. The Dark Side of the Moon effectively played with form, hinting at genre structures as a way (I thought) of getting at other concerns. In Rupture Stephen Shainberg had more fully fused form and content, while also presenting monsters through the use of a particularly subtle visual effect — and yet in the question-and-answer after the film he had seemed to consider “genre” not simply as a function of the content of the story, but as a set of programmatic conventions.

That ended the night, and I began walking home thinking over what I’d seen that day. I’d heard Guillermo del Toro present a vision of horror and horror filmmaking and how those things worked; and I’d seen two examples of what he’d been talking about as well as a documentary about the genre. It struck me that both the fiction films I’d seen had been anti-structure, insisting on an individual’s journey and the individual exploration of the psyche; in these movies social structures were hostile or untrustworthy. But it also struck me that these films were more reserved abut embracing genre than del Toro. The Dark Side of the Moon effectively played with form, hinting at genre structures as a way (I thought) of getting at other concerns. In Rupture Stephen Shainberg had more fully fused form and content, while also presenting monsters through the use of a particularly subtle visual effect — and yet in the question-and-answer after the film he had seemed to consider “genre” not simply as a function of the content of the story, but as a set of programmatic conventions.

What all of them, and Creature Designers as well, had in common was an insistence on the idiosyncratic in filmmaking. On the personal. Which is fair enough. What’s the use of genre stories if not, as with any story, to express oneself? And yet it seemed to me that different filmmakers were conceiving of genre in slightly different ways. At any rate, it had been a full day at Fantasia. And there were nineteen still to come.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.