Kurt Busiek’s Astro City. Also Joyce, Hemingway, Faulkner, and a Tangent on Modernism

This is mostly an homage to Kurt Busiek and Astro City, and to one story in particular, but buckle in because we’re going to cover a lot of rambling ground getting there in a sort of stream-of-consciousness way, taking in stuff by random association — sort of like the streets of Astro City itself…

This is mostly an homage to Kurt Busiek and Astro City, and to one story in particular, but buckle in because we’re going to cover a lot of rambling ground getting there in a sort of stream-of-consciousness way, taking in stuff by random association — sort of like the streets of Astro City itself…

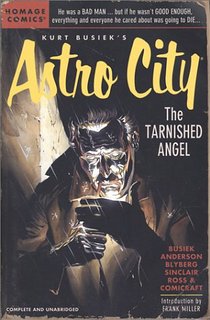

Kurt Busiek’s Astro City is one of my favorite superhero comics. It consistently delivers brilliant, funny, poignant, human stories in a colorful, wonderfully idiosyncratic comic-book world. It is Busiek’s magnum opus — like Bendis’s Powers, it towers above his other work for the big publishers using their branded characters. He brings the sensibilities he honed in the groundbreaking Marvel miniseries Marvels to his own universe and, beneath all the ZAP! BANG! POW!, weaves tales you will never forget.

What Marvels did that was so fresh in 1994 is it “lowered the camera” from the god-like supers knocking each other through buildings and focused in on the ordinary humans down here at street level, wide-eyed and slack-jawed, watching it happen. What impact did the existence of such powers have on their day-to-day lives?

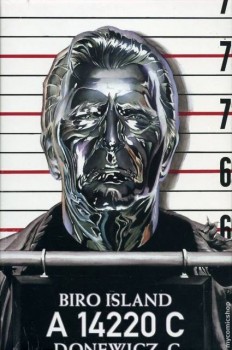

In Astro City the camera is completely unfettered, ranging to the heights to reveal very human dramas among people who have the power to level cities and then zooming down to the alleys to follow a day in the life of a two-bit petty thief who is really a pretty ordinary, decent human being (with the exception that his skin is covered with a steel alloy). Through the course of following Carl Donewicz, aka Steeljack — in the classic story “The Tarnished Angel” — we come to sympathize with and like him, and even find ourselves rooting for him: just once, could one of his heists go off without a hitch and not be foiled by The Jack-in-the-Box? And in Astro City, where narratives don’t always follow the comic-book formula, he does have his day. A fun, feel-good story, that one.

And then there are Astro City stories that rip your heart out. “The Nearness of You,” I contend, is among the great American short stories of the late twentieth century, and I think it could be anthologized as such. (Wizard Magazine does rank it number 6 on their list of “100 Greatest Single Issue Comic Books Since You Were Born.”) Publishers these days would have no problem formatting a four-color comic story into their prose collections. But should they? It is, after all, a comic book.

Twenty-five years ago one of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman stories (#19 “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”) caused a furor when it was nominated for and won the World Fantasy Award for Best Short Story. After that, the committee clarified that a graphic story could not be nominated in that category. (Kind of like when the Oscars got flack for nominating an animated film in the Best Movie category — afterwards the Academy spun off a new category just for animation.)

Twenty-five years ago one of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman stories (#19 “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”) caused a furor when it was nominated for and won the World Fantasy Award for Best Short Story. After that, the committee clarified that a graphic story could not be nominated in that category. (Kind of like when the Oscars got flack for nominating an animated film in the Best Movie category — afterwards the Academy spun off a new category just for animation.)

Graphic fiction has joined the “grown-up” table, and lately is more widely accepted as a legitimate literary form. Indeed, today you can peruse the course listings of English departments at many major universities and find classes on the graphic novel alongside courses on the Künstlerroman, the American Transcendentalists, and Modernism.

Speaking of Modernism… Throughout much of the twentieth century, Modernism held sway. Its basic tenets continued to influence academia through-out the reactionary phase of postmodernism (but after two decades of studying this stuff I still don’t want to attempt a succinct definition of what “post-Modernism” is. At least not in a short aside here — we’ve got other stuff to get to).

I’ll briefly take a shot at summarizing Modernism — at least some key tenets that may be germane to our discussion of comic books. Modernism was a reaction against traditional forms that writers and artists during the rise of modern Industrialism — and especially after WWI — felt were insufficient to wrestle with a world that was becoming soul-crushingly urbanized and that had just witnessed the horrors of the trenches and modern warfare. Modernists were all about blowing up traditional narrative and stylistic techniques — T.S. Eliot was writing “The Wasteland” and Picasso was painting in his Cubist style, tossing the limits of perspective and suggesting even our own eyes were insufficient to perceive reality.

Indeed, Modernists were taking on the monolithic assumption of “Truth” as handed down by people who allowed a World War to messily wipe out millions of lives. They embraced the plurality of societies and peoples, rejecting the dogmatic strictures of religion and cultural norms. “It’s all relative” and “There is no capital-T Truth” were postmodern mantras that grew out of this, although post-mods took those ideas further than most Modernists — sometimes into the realm of absurdity, where all truth and knowledge is deconstructed into nonsense.

This rejection of old forms was expressed not just with avant-garde plotting but with pushing the envelope of language itself — as best exemplified by James Joyce’s Ulysses, that doorstopper of a paragon of Modernist literature.

Ulysses is one of those books with which everyone is familiar but few have read. Oh, many have read some of it, but a small fraction of those brave souls who began the journey have actually made it through and come out the other end. And that’s because Joyce eschewed traditional storytelling, making it unclear — without referring to copious footnotes and annotations supplied by later scholars — who the hell is talking, where they’re at, and what they’re doing there. If Ulysses was a “bugger off” to traditional narrative, Joyce’s next and last major work — Finnegan’s Wake — was a royal flip of the finger to the scholars and academics who had been able to parse through Ulysses and make sense of it. (And by the way, if anyone tells you they really understand Finnegan’s Wake, file them in the same category as Charles Manson proclaiming he got what the Beatles were really saying in “Helter Skelter.”)

Ulysses is one of those books with which everyone is familiar but few have read. Oh, many have read some of it, but a small fraction of those brave souls who began the journey have actually made it through and come out the other end. And that’s because Joyce eschewed traditional storytelling, making it unclear — without referring to copious footnotes and annotations supplied by later scholars — who the hell is talking, where they’re at, and what they’re doing there. If Ulysses was a “bugger off” to traditional narrative, Joyce’s next and last major work — Finnegan’s Wake — was a royal flip of the finger to the scholars and academics who had been able to parse through Ulysses and make sense of it. (And by the way, if anyone tells you they really understand Finnegan’s Wake, file them in the same category as Charles Manson proclaiming he got what the Beatles were really saying in “Helter Skelter.”)

Don’t get me wrong. Joyce was one of the greatest geniuses of the English language. Other postmodernists who copied him and put out stuff that is unintelligible and virtually unreadable to seem “smart” — they’re who really get my goat. And his earlier stuff — A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, “The Dead” — is brilliantly written and accessible. Finnegan’s Wake — as a friend of mine put it — is the proto-language of Ireland speaking its myths to Stephen Dedalus in his dreams. It’s like Joyce burrowed so far down into the core foundations of language, he reached depths where few could go — or follow.

But the other thing Joyce did to eschew traditions with Ulysses was his choice of subject matter and how he treated it. He chose ordinary people in mundane situations but applied the elevated style of Homer to their stories. Hence his protagonist being equated to Ulysses in The Odyssey, even though Leopold Bloom is just a poor sop in a troubled marriage going through an uneventful day in Dublin. The actual events could be summarized in a few paragraphs, but Joyce sweeps it out to hundreds of pages (265,000 words!), faithfully hewing to the narrative beats of The Odyssey, most of what happens to Bloom deliberately parallel to events in that epic.

But the other thing Joyce did to eschew traditions with Ulysses was his choice of subject matter and how he treated it. He chose ordinary people in mundane situations but applied the elevated style of Homer to their stories. Hence his protagonist being equated to Ulysses in The Odyssey, even though Leopold Bloom is just a poor sop in a troubled marriage going through an uneventful day in Dublin. The actual events could be summarized in a few paragraphs, but Joyce sweeps it out to hundreds of pages (265,000 words!), faithfully hewing to the narrative beats of The Odyssey, most of what happens to Bloom deliberately parallel to events in that epic.

Joyce was applying the glowing veneer of myth to the workaday world of “nobodies” — and I think this is commendable, and might be heroic, in a way — rekindling a sense of awe in a drab world we take for granted, elevating the “people that you meet / when you’re walking down the street / each day” to the status of heroes in a Greek tragedy. At least I think this is the case; it’s hard to say, exactly, when it comes to Joyce. (A friend of mine goes further, responding to my reflections here: “And as in all fairness you give it it’s due in terms of its ennobling of modern man through a palimpsest of myth, I emphasize that even more: Joyce, through literature, was attempting nothing short of the transubstantiation of modern life.” Wow. If that’s what he’s doing, I can get behind that!

Over here on my side of the Atlantic, modernists like Hemingway and Faulkner were telling stories that rejected the literature of their fathers in their own ways. Hemingway was cutting every word not necessary to convey the basic picture in the reader’s mind, ruthlessly slashing every adverb and coldly killing every adjective. (Hemingway would never have written that last sentence.) Faulkner went to the other extreme: penning sentences that went on for days, with so many clauses and conjunctions and modifiers that sometimes you need Post-it notes just to remember what the original subject was.

Over here on my side of the Atlantic, modernists like Hemingway and Faulkner were telling stories that rejected the literature of their fathers in their own ways. Hemingway was cutting every word not necessary to convey the basic picture in the reader’s mind, ruthlessly slashing every adverb and coldly killing every adjective. (Hemingway would never have written that last sentence.) Faulkner went to the other extreme: penning sentences that went on for days, with so many clauses and conjunctions and modifiers that sometimes you need Post-it notes just to remember what the original subject was.

Whatever the case, Hemingway and Faulkner were still much more comprehensible than Joyce, which is why their books are more often picked up to be read for pleasure and not just because the professor put it on the syllabus. (Which is one thing to be said for not forcing your audience to have to work too hard to make sense of what the hell you’re talking about.)

But one thing many Modernists had in common was their insistence on the subject matter being “real.” That much they preserved and carried over from their predecessors, naturalists and realists like Stephen Crane. Artifice when it came to the telling? — Hell Yes! The language and structure and narrative forms should be as strange, as alien, as new as possible, but you should be writing about “real” things that happen to “real” people in this “real” world. Which is what put them at odds with the entire genres of science fiction and fantasy. They looked down their noses at all that because it did the exact opposite: hewed to pretty traditional storytelling styles to tell stories about stuff that could never happen.

What they failed to recognize at the time was that science fiction and fantasy were genres that were growing up and hosting their own Modernist revolutions — not in fundamentals of narrative, but against the limits that were imposed on the imagination. Indeed, there was another literary Renaissance going on concurrent to Modernism, but the latter held such powerful sway with the “in” literary circles and at Ivy League universities that it went largely unnoticed — except to the millions of readers in the general public who were discovering T.H. White and J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, Ray Bradbury and Leigh Brackett and Ursula Le Guin.

What they failed to recognize at the time was that science fiction and fantasy were genres that were growing up and hosting their own Modernist revolutions — not in fundamentals of narrative, but against the limits that were imposed on the imagination. Indeed, there was another literary Renaissance going on concurrent to Modernism, but the latter held such powerful sway with the “in” literary circles and at Ivy League universities that it went largely unnoticed — except to the millions of readers in the general public who were discovering T.H. White and J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, Ray Bradbury and Leigh Brackett and Ursula Le Guin.

The instigators of this other revolution have had far more influence on twenty-first-century culture than their modernist contemporaries (Of course you can disagree as to whether that is for better or for worse. I’ve known my share of academics who would bitterly suggest we scificionados all just hop into our Millennium Falcons, fly off to Hogwarts, and leave their serious culture alone — while they shake their fist and yell, “Take the One Ring with you, and shove it up your arse when you get there!”).

That tension was still alive and palpable when I first entered university, and even in 2002 when I argued that the Inklings (the British writing club that included C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Charles Williams) was a worthy topic for a master’s thesis. But the Modernists are dead now, and most of the postmodernists are retired. And academia is struggling to catch up with this whole overlooked vein of formative twentieth-century literature.

But I digress.

Back to comic books. It seems to me that the graphic novel is a form that Modernists could get behind. It breaks from traditional narrative forms — heck, when Modernism began to coalesce as a movement, comic books didn’t even exist. The only place sequential art could be found in those days was on the Sunday funny pages (The first modern comic book, Famous Funnies, was published in 1933, and it actually just collected newspaper comic strips).

Back to comic books. It seems to me that the graphic novel is a form that Modernists could get behind. It breaks from traditional narrative forms — heck, when Modernism began to coalesce as a movement, comic books didn’t even exist. The only place sequential art could be found in those days was on the Sunday funny pages (The first modern comic book, Famous Funnies, was published in 1933, and it actually just collected newspaper comic strips).

So let’s consider Busiek’s Astro City and Joyce’s Ulysses together for a second (something that has never been done before and I’m sure will never be done again). Don’t both, in very different ways, fulfill the tenets of what the Modernists were after? Both break with traditional narrative forms (check): Joyce by his deliberately obscure narration and his complex (brilliant but often confounding) use of language; Busiek by telling his story with words woven in with sequential art, a narrative form that had previously been relegated to low culture and “kiddie fare.” Joyce was taking mundane characters and imbuing their stories with the trappings of myth. Busiek takes myth-like characters and imbues them with real human emotions and drama. It’s like they’re both taking myth and reality and infusing them together but going in two opposite directions with it — still, directions that take them from a traditional “center.” One takes the low and elevates it to Olympus; the other takes Olympus and brings it down to street level.

Both approaches, I would argue, create opportunities for revealing to us more about ourselves, about human nature, and about the human condition. The Modernists were all about mixing high and low culture. Part of the bias against taking the work of someone like Busiek seriously is that he happens to be using a form traditionally classified as for children and “slow” adults, and which is consequently far more accessible. Joyce, on the other hand, is dense and obtuse and you have to really be sophisticated and put in the hours to get anything out of it.

I need not point out that this last distinction is not a criterion for judging between good and bad art. Anyone can pick up and easily understand The Great Gatsby or To Kill a Mockingbird or The Catcher in the Rye. “Hard to make heads or tails of” is not a prerequisite of great literature. Even the groundlings in the pit of the Globe Theater could follow Hamlet. The only reason Shakespeare is challenging to some readers today is because of 400 years of evolution of the English language — and with just a bit of perseverance, even kids in junior high and high school can start reading and appreciating Shakespeare.

I need not point out that this last distinction is not a criterion for judging between good and bad art. Anyone can pick up and easily understand The Great Gatsby or To Kill a Mockingbird or The Catcher in the Rye. “Hard to make heads or tails of” is not a prerequisite of great literature. Even the groundlings in the pit of the Globe Theater could follow Hamlet. The only reason Shakespeare is challenging to some readers today is because of 400 years of evolution of the English language — and with just a bit of perseverance, even kids in junior high and high school can start reading and appreciating Shakespeare.

“The Nearness of You” is a piece of great art. I’ve read comics all my life, but it is the only one that makes me start to tear up just thinking about it.

Like Busiek’s best stories, it takes us into the POV of an ordinary guy living in this extraordinary world where the nightly news often features the latest dustup between super-powered beings doing extensive damage to some part of the city (this — the consequence of epic battles to ordinary people and the unfortunate neighborhoods that are Ground Zero — is an aspect the Marvel Cinematic Universe has started to pay more attention to, and you can bet your sweet bippy that Busiek was a direct influence on Joss Whedon and other later Marvel scribes).

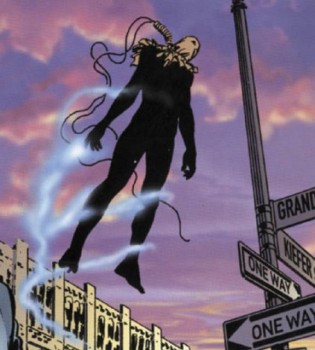

The protagonist, a young man named Michael Tenicek, is plagued by dreams of a woman. He feels a powerful affection for her although he has never met her. The dreams bother him so much that he turns to drugs and other forms of escape to try to rid himself of the haunting memories of the woman. Nothing works, though, so he trudges up Shadow Hill one night to seek out the Hanged Man, the mysterious, ethereal guardian of the Hill who appears as a floating, hanged man, his face still covered by a gunnysack and the rope trailing along behind him from his neck.

The protagonist, a young man named Michael Tenicek, is plagued by dreams of a woman. He feels a powerful affection for her although he has never met her. The dreams bother him so much that he turns to drugs and other forms of escape to try to rid himself of the haunting memories of the woman. Nothing works, though, so he trudges up Shadow Hill one night to seek out the Hanged Man, the mysterious, ethereal guardian of the Hill who appears as a floating, hanged man, his face still covered by a gunnysack and the rope trailing along behind him from his neck.

And let me pause here just to say this: The Hanged Man is one of the Coolest. F***ing. Things. In a comic book. Ever.

(And by the way, Busiek has single-handedly populated an entire city with cool stuff like that, working out histories for the various neighborhoods, a timeline for when the first superpowers started showing up and for when various super-groups have come and gone, and back-stories for all of these characters as if they had been running in their own comics going back to the Golden Age. Check out the complete cast of characters for Astro City on Wikipedia sometime. Marvel and DC took decades and hundreds of writers and artists to build up their labyrinthine pantheons. What Busiek has done is create a comparably rich superhero universe from the ground up. Many of his creations, of course, are thinly-veiled mirrors of or homages to Marvel and DC characters, but it is a sustained work of deliberate pastiche that is truly impressive.)

Anyway, Michael meets the Hanged Man, and the Hanged Man lays down some spooky exposition.

[SPOILERS AHEAD]

You see, a man and a woman once fell in love. They got married, had a life together. Things were pretty good. Then one of those epic smackdowns happened, this time between The Honor Guard (Astro City’s version of The Avengers or the Justice League) and a supervillain known as Time Keeper. Time Keeper did what supervillains often try do: alter reality as we know it and generally screw things up, messing around with the timeline and parallel universes and all that. The heroes had to fill in the breach and repair the rupture in the fabric of reality. This superhero-backstory part of the plot is pure Marvel-Infinity-War / DC-Crisis-on-Infinite-Earths silliness. Bad guy tried to blow everything up; good guys saved the day.

But down here on street level, there were repercussions that would never be reported on the nightly news. When the good guys restored reality, they stitched it back up as best as they could, but it was not perfect. Left a seam. A few little bits of reality — not enough for any major newspaper to notice — winked out of existence. One bit was the woman. Not that she died: she just never existed. In this newly-patched-up universe, she was cut-and-pasted out.

Except Michael retained all his memories of her, buried somewhere in his subconscious, and it’s those memories that have been haunting and torturing him. He’s doomed to be in love with someone who never was!

And then — oh man, here’s the kicker — the Hanged Man helpfully offers to erase those memories: to fix this one place where the stitching was not perfect, and bring Michael’s brain back in line with reality as it now is. No more to be haunted by a woman who is not part of that reality.

And Michael chooses to… No. Sorry. I’m not going to give that away. I’ll just say that even now, typing up this synopsis, I’m getting a little teary-eyed. This one does that to me.

Comics are now allowed at the adult table, because artists in the genre have proven that the form can be used to create great works of literature. But not just the stories where the “real world” is depicted in graphic form — works like Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Craig Thompson’s Blankets. (Incidentally, if I were teaching a college class on the bildungsroman or the Künstlerroman novel today, I would consider including — alongside the usual suspects like Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man — any or all of those last three.) There are also great, sophisticated stories using all the Saturday-matinee trappings: giant monsters and bug-eyed aliens, superheroes and villains, ray guns and time machines. In the hands of a writer like Busiek, these tropes can be used to tell stories as gritty as Crane or Steinbeck, as emotionally resonant as Fitzgerald or Ishiguro.

The inclusion of comic books in the curriculum is not a case of colleges being dumbed down; it is a case of comic books having gotten smart enough for college.

“The Nearness of You” was published by Image Comics as Kurt Busiek’s Astro City issue ½ with a cover date of December 31, 1996. It is collected in the trade paperback Kurt Busiek’s Astro City: Confession (1999) with a list price of $19.99. It is still in print. (And the main story collected in Confession is pretty bad-ass too.)

You picked my favorite, Nick!

The first comic book was FAMOUS FUNNIES, not SUNDAY FUNNIES.

I’ve been promising myself to re-read all my Astro City collections, and after reading this…today’s that day to start. If I can figure out the right order.

Thomas, a man of distinctive taste!

R.K.: Enjoy revisiting the City!

LWE,

Thanks for the catch — I’ve corrected the title in the post.

I can’t believe 20 years have gone by. The manager of the Bookery Fantasy in Fairborn OH kept nagging m to rad it when the first mini series came out and I kept saying no I had enough titles already to keep up with. This was a rare instance of him pushing a title on me as he knows my likes and don’t cares are all over the map. He finally GAVE me issue one and it was love at first reading and been here ever since. Lesson learned. The owner of the Bookery in all these years has only pushed one title on me Xenozoic Tales and I wish Mark Schultz would get back to it.

Ah, Cadillacs and Dinosaurs – those were the days!

If I may add some small detail-the original Nearness of You was part of the Wizard Magazine Presents 1/2 series and shared the Homage logo which came out between issues 3 and 4 of the Volume 2 series. It was later reprinted by Image/Homage coming out between issues 12 and 13 with a new over and the original cover placed on the back without cover copy. And YES the Hanged Man is one of the more intriguing characters (I’m a DC Comics Spectre fan). I don’t bother with the trades (a money issue) but have all the comics as they came out and bagged and they are one of top titles never tolet loose of (after years of selling in a moment of money needs I don’t sell my comics anymore after discovering invariably my money panic was generally settled down after a week or two.