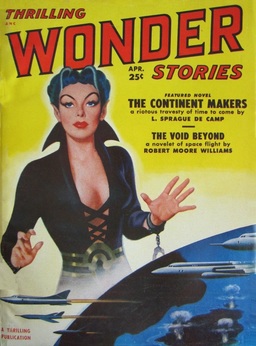

Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1951: A Retro-Review

I felt like looking at a classic pulp from the great late stages of the true SF pulps.

I felt like looking at a classic pulp from the great late stages of the true SF pulps.

A moment of definition is in order here: I consider a true pulp magazine to have been printed on pulp paper, in approximately the traditional pulp size (7″ by 10″), during the heyday of the SF pulps (say, 1926-1955). This is meant to exclude digests (like Astounding after about 1943; and most SF magazines after 1955), and of course slicks. The great pulps (in my opinion) of the early 1950s were the Standard Magazines companion pair, Thrilling Wonder Stories and Startling Stories, and Planet Stories (published by Love Romances).

So this is Thrilling Wonder Stories for April of 1951. Thrilling began publication in 1936, though it was essentially a direct descendant of Wonder Stories, which was founded by Hugo Gernsback after he lost control of Amazing, first as two magazines, Air Wonder Stories and Science Wonder Stories, that soon merged into one. The editor is uncredited but at this time was surely Sam Merwin, Jr., who took over the magazine in 1945, and who left at the end of 1951, Sam Mines taking over. Sam Merwin, little enough celebrated at the time, was actually a quite effective editor, raising the quality of Thrilling Wonder Stories and Startling Stories to at least shooting distance of Astounding – perhaps the quality at the top wasn’t as good, but the vibe was a bit more entertaining, less didactic.

Indeed, I discussed this premise – that Thrilling Wonder and Startling were nearly the equal of Astounding – with a few other folks who know the magazines of that time as well or better than I do, and we came to the conclusion (some holding this view more strongly than others) that in about 1948-1950 that was a very defensible statement, but that by 1951 they were falling behind. And the reason seemed obvious once suggested: the appearance in late 1950 of Galaxy (not to mention the appearance slightly earlier of F&SF) provided a new market that quickly attracted most of the best stories that Campbell didn’t or couldn’t buy.

[Click any of the images for bigger versions.]

[Click any of the images for bigger versions.]

Merwin’s other editorial jobs in the field were also promising, though none lasted terribly long. The cover is likewise uncredited, as are the interiors. Signatures can be detected for Vincent Napoli on one story, and Peter Poulton on another. Several of the stories have art that looks a bit like Virgil Finlay, but then Napoli’s work resembles Finlay to some extent as well, so perhaps Napoli did a lot of the art in this issue.

The pulps in those days were known for their vigorous letter columns — they served some of the same purpose that blogs and Facebook and even Twitter serve these days for fans. The Thrilling Wonder column was called The Reader Speaks. It opens with what serves as an editorial, this time talking about the stultifying effects of entrenched institutions.

The letters follow, several pages in small type. Contributors this issue are Algis Budrys (still a year away from his first published story), William F. Temple, Poul Anderson, Mary Wallace Corby, Raymond Wallace, Bob Hoskins, Walter A. Willis, Joseph A. Phipps, Bernie O’Gorma, Ann B. Nelson, Joe Gibson, Tom Pace, Derek Pickles, Tom Covington, Don Jacobson, and Albert J. Lewis. Lots of names to reckon with — writers like Temple and Anderson, editors like Hoskins, a superfan in Walt Willis.

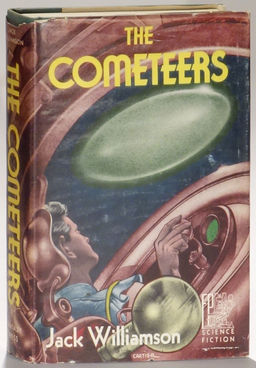

There are two more features: The Frying Pan, a Fanzine Commentary, in which The Editor takes on an article by Charles Stuart in the fanzine Aleph Null, in which Stuart complains that sex is a forbidden theme in SF. The Editor, in essence, argues that sex is more present that Stuart thinks (and I tend to agree that there was more treatment of sex in SF of that time than the popular wisdom would suggest). There is a book review column as well, also by The Editor, covering Lewis Padgett’s A Gnome There Was, Clifford Simak’s Cosmic Engineers, and Jack Williamson’s The Cometeers.

I also thought I’d mention the ads a bit. Most of them are the usual ads from the pulps those days: correspondence courses, rupture aids, poli-grip, etc. But there is one interesting genre-specific ad: for the new movie from Howard Hawks: The Thing From Another World.

So, to the stories.

Complete Novel:

The Continent Makers, by L. Sprague de Camp (36,000 words)

Novelets:

“The Void Beyond,” by Robert Moore Williams (11,500 words)

“Milords Methusaleh,” by Carter Sprague (17,400 words)

Short Stories:

“The Replaced,” by Margaret St. Clair (2,800 words)

“Overtime,” by Mack Reynolds (6,100 words)

“I’m a Stranger, Myself,” by Dallas Ross (1,400 words)

“The First Long Journey,” by Raymond Z. Gallun (5,400 words)

“Deception,” by Matt Lee (6,200 words)

Despite appearances, there are no true “Little Known Writers” this issue (by my definition), largely because three names shown are pseudonyms (and two writers actually have two stories each in this issue).

|

|

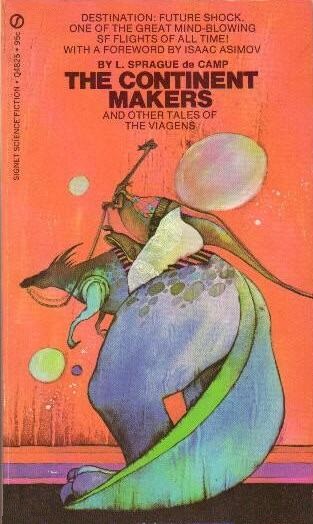

But first, the best known writer and best known story in this issue, L. Sprague de Camp’s “The Continent Makers.” It’s listed by the magazine as a “Complete Novel,” which was often a gross exaggeration in pulps of this day, but it should be said that some of the pulps, the Standard Group notable among them, really did publish full length novels in single issues, up to 60,000 words. “The Continent Makers” is a bit shy of the Hugo and Nebula definition of “Novel” (40,000 words), but it’s plenty long enough that it might have been published alone in book form, or as an Ace Double half. However, it was instead chosen as the title story of a collection of Viagens Interplanetarias stories first published in 1953, and perhaps for that reason, it’s never seemed to me to get as much notice as some of de Camp’s other work in that series.

Sprague de Camp (1907-2000) was one of the great SF writers of the “Modern Science Fiction” period — that is, of John Campbell’s birthing, as it were. He was named a Grand Master in 1979. De Camp actually first appeared in Astounding in September 1937, the last issue before Campbell took over, but he quickly became popular working for Campbell, in both Astounding and Unknown, often in collaboration with Fletcher Pratt. His most famous collaborations with Pratt were the Harold Shea Incomplete Enchanter stories, and in fact the first two of those are among this year’s Retro-Hugo nominees.

Sprague de Camp (1907-2000) was one of the great SF writers of the “Modern Science Fiction” period — that is, of John Campbell’s birthing, as it were. He was named a Grand Master in 1979. De Camp actually first appeared in Astounding in September 1937, the last issue before Campbell took over, but he quickly became popular working for Campbell, in both Astounding and Unknown, often in collaboration with Fletcher Pratt. His most famous collaborations with Pratt were the Harold Shea Incomplete Enchanter stories, and in fact the first two of those are among this year’s Retro-Hugo nominees.

De Camp wrote several extended series — the Shea stories, the Gavagan’s Bar tales, and many more, but his most extended and arguably most popular series is a future history called Viagens Interplanetarias, set in a future dominated by the Brazilians, where Earth has ventured to a number of nearby star systems using only slower than light travel. De Camp wrote in this series to the very end of his career: his second to last novel, The Venom Trees of Sunga (1992), is a Viagens Interplanetarias story.

Many of his VI stories concerned the planet Krishna. The natives are egg-laying and have antennae, but otherwise are remarkably human appearing and in fact most of the stories concern at some level sexual attraction between humans and Krishnans. Krishna’s technology is a couple of centuries behind Earth’s, and politically they are divided into a variety of often warring states with differing political philosophies — a lot like Earth, that is, except that by the time of de Camp’s stories there is a fairly strong world government.

The Continent Makers is sort of a Krishna story, in that two of the main characters are from Krishna, but they are visiting Earth. They are Jeru-Bhetiru and her fiancé, Varnipaz bad-Savarum, who is studying Earth law in order to help him in his role as essentially Attorney General for a small nation on Krishna. The main human character is physicist Gordon Graham, who is asked to escort Jeru-Bhetiru, or “Betty,” around town while her fiancé is away. Graham, of course, falls for the beautiful and habitually underdressed (by Earth standards) Betty immediately, and she seems to return the attraction, which is embarrassing when Varnipaz turns up. All is fine, though, as the Krishnans explain that marriage is purely a practical arrangement, having nothing to do with love, and anyway humans and Krishnans aren’t interfertile so where’s the harm?

This is really a side issue to the main action, which begins more or less immediately with an attack on Graham. He and an unexpected ally, a World Federation cop, fight off the attack and Graham soon learns that the whole thing has to do with a plot involving a project Graham has been assisting. There is a plan to set off some bombs under the ocean, causing a release of sufficient magma to form a new continent. This will help with the population on Earth (I shudder to think of the ecological consequences if such a thing could actually be done!), but it seems that the real estate laws (as Varnipaz is happy to explain) mean that the timing of the formation of the new continent is critical. A couple of alien races and some greedy humans have plans to profit by starting the process early. Graham and the cop, along with the brave Krishnans, run around for a while figuring all this out, then go sailing off to an island at the center of the planned new continent, to foil the bad guys. It’s all a bit strained, but that’s not the point. It’s a pretty fun romp most of the way, with lots of off the cuff grace notes like the “Churchillian Society,” which attempts to prove that George Bernard Shaw could not possibly have written the plays attributed to him — the real author must have been Winston Churchill.

On to the pseudonyms. If I said that one of the well-known authors in this issue had another story published under a pseudonym, I bet a lot of people might have looked at the name “Carter Sprague” in the TOC and guessed that maybe de Camp used that name. Well, “Carter Sprague” is a pseudonym, but not for de Camp — instead, for the magazine’s editor, Sam Merwin, Jr. In fact, Merwin published a fair amount of SF, much of it (that I’ve read) reasonably enjoyable if slight. His main market, perhaps not surprising, was the magazines he edited, and while he occasionally used his own name, he usually used pseudonyms, primarily “Carter Sprague” and “Matt Lee.” Both those names appear in this issue.

“Milords Methusaleh” is set on another planet on which several humans crashlanded. The inhabitants are basically human, but they have compressed lifespans, apparently because the year on their planet is shorter it is closer to its primary. So the humans are regarded as gods because they seem to be immortal. They seem to use their godhood mainly in arranging for sexual relationships with a series of the short-lived natives — and the woman in their group, sexistly portrayed as originally too concerned with science “to be a woman” (instead she’s “scraggly” and “mannish”), is now obsessed with reenacting Earth history on this planet (Plania), as well as on maintain relationships with various of the men. Oh, and she’s beautiful too, now. (A theme that Merwin would return to this issue. His stories often featured lots of at least implied sex, explaining perhaps his response to the fanzine article.) Tables are turned when the Planians develop spaceflight, which finally spurs the lazy Earthmen to real action on getting back home — and a highly implausible solution to the Planians already highly implausible central problem.

As “Matt Lee,” then, Merwin wrote “Deception,” in which a couple of scientists, including the repressed woman scientist Seana Ryan, discover evidence of a crashed ship from Jupiter’s moon Callisto. They immediately organize an expedition to Callisto, with Seana Ryan, her cliche German colleague, and with an annoying but competent macho space captain. When they get to Callisto and meet the Callistans, who are intelligent and well-disposed towards friendship, the only remaining question is why was the image of a Callistan found in the wreck of their ship so uncharacteristic? Well, why are the captains’ pinups so uncharacteristic? And, thus, isn’t Seana Ryan helpful in the cause of interspecies amity when she, er, dresses like a woman, and thus reveals that maybe the pinups weren’t quite so unrealistic? Yes, it’s a pretty sexist story, and in a very predictable direction.

|

|

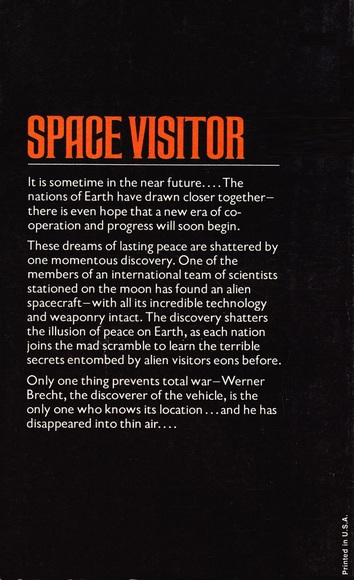

For some time in the late 70s, Ace promoted Mack Reynolds as

“Voted the Most Popular Science Fiction Author by the readers of Galaxy and IF”

The well-known writer who appeared twice in this issue is Mack Reynolds. Reynolds (1917-1983) began his career in 1950, with no fewer than 18 stories appearing that year. He really never became truly a name to reckon with, but by the ’60s he was a regular in John Campbell’s Analog, famous as a socialist who could get along with a cranky conservative like Campbell. Reynolds’ politics were a flavor of socialist, but the rest of his attitudes seem to me overwhelmingly Campbellian, so I don’t find their rapport that odd. He kept publishing regular, short fiction and many many novels, right up to his death at a fairly young age.

The two stories in this issue, obviously, are early work. The pseudonymous piece is “I’m a Stranger Myself,” as by “Dallas Ross,” a name he used a half-dozen times in the first two very busy years of his SF career. It’s a very slight story, about a rural farmer who encounters a Martian. The rube refuses to believe the Martian, who vaingloriously reveals his planet’s secret invasion plans… of course, the supposedly stupid farmer has a secret of his own up his sleeve. Slight, as I said, but effective enough. The story under Reynolds’ own name, “Overtime,” is about a spaceship that loses its navigation computer in an accident. There is no way to compute a course home — except for the human navigator, only kept on board because of union rules or something, and who has been mercilessly ridden by his crewmate. But there is no way the human can complete the complicated calculations in time — except… well, except for a twist that I found hard to believe. Still, it’s acceptable pro-level hackwork.

“The Replaced” by Margaret St. Clair is a curious little story about a group of elderly people taking a vacation on an artificial planetoid at which the servers are all robots from Venus — apparently when humans came to Venus they found empty cities and no Venusians — just robots. But the people start to feel different under the robots’ care, leading to a rather odd, ambiguous ending.

Robert Moore Williams’ “The Void Beyond” posits that space travel is so painful that only young men — no women, and no one over 30 — can survive it. Eric Gaunt is a veteran captain, 28 or so, who is disgusted when a woman tries to come aboard, having bought her ticket legally with her ambiguous name, Frances Marion. So then the woman stows away… and when they catch her she insists that the problem is in their head and if they just exhibit will power they’ll be able to tolerate space, just like she will. The ending is a mild twist. Generally a pretty silly idea and execution, with a predictable romance tacked on.

Finally, Raymond Z. Gallun’s “The First Long Journey” is another story about man overcoming the incredible difficulty of space travel. This is about a man on the first trip to Mars, and his difficulty believing he’ll make it, all alone as he is. He whiles away the time remembering a girl he used to know, talks to himself a lot… and nothing much happens, certainly nothing that convinced me.

Rich Horton’s last Retro Review for us was the October 1962 issue of Amazing Stories.

Interesting fact: Mack Reynolds would go on to write a YA novel called Mission to Horatius that is in fact the first ever Star Trek novel, published shortly before Blish’s more famous Spock Must Die!.

Thanks–these looks at old sf magazines are interesting.