Captain Alatriste by Arturo Pérez-Reverte

Was once a captain,

the story goes,

who led me in battle,

though in death’s throes.

Oh, senores! What an apt man

was that brave captain.

— E. Marquina, The Sun Has Set in Flanders

Spain’s Golden Age ran from roughly 1492, the final year of the Reconquista, until 1659 and the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees with France. During that period seemingly endless rivers of gold and silver from the kingdom’s colonies around the world flowed into its coffers. The disciplined soldiers of her vaunted tercios (commands of about 3,000 men) were respected and feared across Europe. Great cathedrals and palaces were built and painting and literature flourished as never before.

But a rot had set in, unseen by many, by the early 17th century. Inflation, corruption, expulsions of Jews and Moors, and endless wars would render Spain a mortally wounded empire that would slowly wither away over the subsequent two centuries. In 1623, though, Madrid is a glorious city of poets and dashing swordsmen. One of the greatest of the latter is Diego Alatriste y Tenorio, the hero of Captain Alatriste (1996) by Arturo Pérez-Reverte. It’s been a while since I reviewed a historical adventure, so I decided to dive into the first book in this still-running series.

Disappointed with the lack of information about the Golden Age in his daughter’s textbooks, Pérez-Reverte took it upon himself to write a book exploring that dramatic period. His most obvious inspiration were the swashbuckling historical romances of Alexandre Dumas. Undoubtedly influenced by two decades as a war correspondent, his exposure to the darkness of combat also permeates Captain Alatriste.

Alatriste is a veteran of years of conflict with Spain’s recalcitrant subjects in the Netherlands and the Turks, having run away as a drummer boy at the age of 13. Now, some thirty-odd years later, the recently ended truce with the Netherlands has brought him back to Madrid. Struggling to make a living with the only skills he posseses, Alatriste sells his sword and strong arm to whomever will pay. In the past he has been hired to kill one man’s rival at court, and the lover of another’s wife. In this novel, the first of seven to date, he and the Italian swordman, Gualterio Malatesta, are hired to waylay and rob two men. Initially told not to hurt the strangers too badly, they are later given conflicting orders to, in fact, kill them. During the attack Alatriste comes to believe things are not as simple as they seem, as well as being struck by the honor of one of his two intended victims. The rest of the novel involves the fallout from Alatriste’s decision to prevent the men’s deaths, as powerful men at the center of the Empire’s complex and corrupt power structure turn their attention to the veteran sell-sword. And that’s it. That’s pretty much the plot of Captain Alatriste.

Yet that gives not the slightest hint of the verve and excitement that animate the telling of this story. The book bristles with danger and excitement. It moves with vigor and doesn’t waste a moment, nor is it weighed down by pointless digressions. It is a short book and Pérez-Reverte avoids squandering any chapters on harmful distractions.

Yet that gives not the slightest hint of the verve and excitement that animate the telling of this story. The book bristles with danger and excitement. It moves with vigor and doesn’t waste a moment, nor is it weighed down by pointless digressions. It is a short book and Pérez-Reverte avoids squandering any chapters on harmful distractions.

The villains, whether lurking in the shadows of power or facing Alatriste with sword in hand, are a colorful collection of dastards, several of whom, we learn, will plague the captain for many years to come.

Alatriste took one step toward him, and the Italian looked at the sword in his hand. On his knee, uncomprehending, the wounded youth shifted his eyes from one to the other.

“There is more to this than we thought,” the captain stated. “So we will kill them another day.”

The Italian stared even harder. His smile grew wider and more incredulous, and then disappeared. He shook his head.

“Your are mad,” he said. “This could cost us our necks.”

“I will take responsibility.”

“So?”

The Italian seemed to be thinking it over. Then, with the speed of a comet, he lunged at the Englishman with a thrust so forceful that had Alatriste not blocked his sword it would have pinned the youth to the wall. Stymied, the black-clad figure whirled toward the captain with an oath, and this time it was Alatriste who had to call on his instincts as a swordsman to fend off a second thrust, which came within a hair of the site of his heart. The Italian had attacked with the most vicious intentions in the world.

“We will meet again!” he cried. “Somewhere.”

And kicking over the lantern as he ran, the Italian disappeared into the darkness of the street, again a shadow among shadows. From far away, his laugh echoed for an instant, like the worst of auguries.

Unlike another great swashbuckling hero, Captain Peter Blood (discussed here at Black Gate by me and Howard Andrew Jones), Diego Alatriste is the subject of an empire about to begin its fall, not in the midst of its great upward trajectory like England. Pérez-Reverte has forged a hero with the courage to face the dangers of the battlefield, and enough insight and experience to stand against the corruption and intrigue of 17th century Spain. He strives to be an honorable man, once having refused to participate in the expulsion of the Moriscos of Valencia, yet the times have driven him to do dishonorable things. He has been a hero in the past, and may be one yet again, but it isn’t easy. When the opportunity occurs to stay true to his deeper convictions he jumps at it, even though it clearly portends danger, if not death, for himself.

Unlike another great swashbuckling hero, Captain Peter Blood (discussed here at Black Gate by me and Howard Andrew Jones), Diego Alatriste is the subject of an empire about to begin its fall, not in the midst of its great upward trajectory like England. Pérez-Reverte has forged a hero with the courage to face the dangers of the battlefield, and enough insight and experience to stand against the corruption and intrigue of 17th century Spain. He strives to be an honorable man, once having refused to participate in the expulsion of the Moriscos of Valencia, yet the times have driven him to do dishonorable things. He has been a hero in the past, and may be one yet again, but it isn’t easy. When the opportunity occurs to stay true to his deeper convictions he jumps at it, even though it clearly portends danger, if not death, for himself.

I think that is one of the deeper things Pérez-Reverte is trying to accomplish with the character. In an interview he stated that while Spain always produced noble and self-sacrificing people, there were also always priests, politicians, and kings burning them or reducing them to poverty. It is the corrupt and faltering Spanish society that men like Alatriste struggle against, often unsuccessfully, to be the men of honor they long to be.

The captain is also a stoic not given to bragging, which is, in a country where so much depends on how one presents oneself, an anomaly:

As for Diego Alatriste, he carried his hauteur and pride inside, and exhibited them only in his bullheaded silences. I have said already that unlike many braggarts who twirl their mustaches and talk loudly on street corners and at court, the captain was never heard to preen on the subject of his long military career.

His silence, though, is overcome by the way the novel is narrated. We hear the story, many years after its events have transpired, as told by Íñigo Balboa y Aguirre. Thirteen at the time of the story, he is the son of one of Alatriste’s comrades killed in Flanders. He was sent to Madrid by his mother to be raised and trained by Alatriste. We see things through the eyes of a still somewhat innocent boy, filtered through his much older and aware self. As much as the novel tells the story of Captain Alatriste, it also tells that of Íñigo as he matures against the backdrop of his master’s adventures and his own involvment in them.

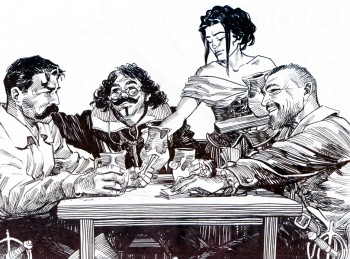

It is in Íñigo’s voice we hear a love letter to a lost time and place — the Madrid of his childhood. It is his recollections, descriptions of poets, priests, and rogues both high and low, and the places they lived and frequented that is the true heart of this book. Over the decades between the events of the novel and his recounting them, the city as it existed in his youth is no longer there, lost to time and national disaster. With descriptions of “blue, luminous Madrid mornings so cold that it takes your breath away,” hilarious tellings of duels in verse between the poets de Quevedo and de Góngora, or the conversations about life and politics between the captain and his friends in the Tavern of the Turk, through Íñigo, Pérez-Reverte reveals a city that hums with beauty, wonder, and above all, life. More even than Alatriste’s effort to remain a man of honor, Íñigo’s sorrow for a Madrid no longer in existence, gives Captain Alatriste a somber feel and paints over many of its brightest moments in sorrowful shades of gray.

There is too much more to write about here in detail. There are splendid secondary characters who will also figure in many of the future novels: the poet de Quevedo, Angélica de Alquézar, who is “as perverse and wicked as only Evil in the form of a blonde eleven- or twelve-year-old girl can be,” and the sepulchral president of the Inquisiton, Fray Emilio Bocanegra. The translation by Margaret Sayers Peden is never stilted, flowing naturally and compellingly.

It is important to me that a historical novel not portray the past through modern eyes. The past is not the present, and its inhabitants did not act with the same morals or beliefs we do today. Never once, even at his most modern sounding, did I mistake the good captain for a modern man. As much as he rebels against parts of the society of 17th century Madrid, he is also a part of it, motivated by the same beliefs and attitudes as his countrymen.

It is important to me that a historical novel not portray the past through modern eyes. The past is not the present, and its inhabitants did not act with the same morals or beliefs we do today. Never once, even at his most modern sounding, did I mistake the good captain for a modern man. As much as he rebels against parts of the society of 17th century Madrid, he is also a part of it, motivated by the same beliefs and attitudes as his countrymen.

Captain Alatriste is a terrific excursion into a part of the past I am not that familiar with. As someone with Dutch and English ancestry, the Spanish have always sort of been the bad guys for me. As a consumer of Hollywood swashbuckler movies, they have definitely been the enemy. Here, I get to see things from the other side, a nice historical corrective, as it were. There are six more novels in the series, with another two planned, but as yet unpublished. I think I will be reading them myself in short order.

NOTE: In 2006 a movie starring Viggo Mortenssen was made in Spain. By all accounts it’s pretty, but mediocre. There’s a Spanish TV series based on the characters, comics for adults and kids, and an RPG. The novels are among the most successful ever published in Spain. And there’s a comment made in Captain Alatriste that clearly links it to one of the greatest swashbuckling novels of all time, but I’ll let you discover that yourself.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him. You can read some more thoughts on The Wake here.

I discovered these books several years ago and fell in love with them immediately. Just as there can’t be enough Errol Flynn or Tyrone Power swashbucklers, there can’t ever be enough books like this. The next in the series, Purity of Blood, is, I think, the best of them all. One of the best things about them is how golden age Spain itself (as you say, a time and place few of us are familiar with) is a character that’s as important as any other in the tales. I can’t recommend these wonderful books too highly.

It is a terrific novel. I haven’t read any of the sequels. Perhaps I’ll track them down. The movie was well done. It’s no masterpiece, but still worth viewing.

“The Adventures of Gil Blas” grants another view of roughly the same period in Spain, though in the form of a picaresque rather than a swashbuckling adventure story.

@Thomas P – I am really glad I picked it up last week, pretty much at random. I’ve read a few interviews with Pereze-Reverte, and one of the reasons he’s written them was to rectify the huge gap in the Spanish curriculum about the period, both the bad and the good aspects of it.

@Ken L – Thanks. I’ve wanted to read more about Spain in general for a while now. I’m also curious about Cervantes’ novella collection, Novelas ejemplares, set in Seville, about sixty years earlier. Supposedly, it was part of the inspiration for Leiber’s Lankhmar stories.

Library hold placed. After “Don Quixote” novellas strike me as light and refreshing.

Very nice write-up. I’m also a fan of the good Captain and have greatly enjoyed the novels.

When you mentioned that there were 7 published, I thought I had missed one. A quick check revealed that the Puente de los Asesinos (Bridge of the Assassins) was published in 2011 in Spain, but has not yet been translated into English.

I couldn’t find a date for when that will occur. Do you, by chance, know?

Thank you!

Thanks. So glad I finally read this.

As to the translation, I had no luck either. Folks think the translator, Margaret Sayers Peden, is backlogged and almost 90, so there’s just been a super long delay. The Siege (2010) has been available in English for a while.

I believe that “The Siege” was translated by Frank Wynne, not Margaret Sayers Peden, but your point is well taken.

Hopefully, another translater as skilled as Mrs. (Ms.?) Peden will be found to translate the latest Capitain Alatriste novel. I’m itching to get back to 17th Century Spain.

Thanks so much for this fantastic post. I found the Alatriste novels after having read Perez-Reverte’s modern novels, and while those are magnificent, particularly The Club Dumas and the Flanders Panel, the Alatriste novels are my favourites.

A couple of points that may interest you: the translations may be better than you imagine. I’ve read them in both Spanish and English, and they are virtually identical.

Perez-Reverte came up with the idea for the character while in a bar in the Plaza Mayor, or so says a signed photo that used to hang in the bar. It’s been taken down by the owner as apparently someone tried to steal it one day. Even though I’ve been there often – or perhaps because of that – I’ve blanked on the name of the bar. Gallago?

There is a bar/restaurant down the Cava Baja leading out from the Plaza Mayor called Capitan Alatriste. In the bar section there’s a huge mural that’s supposed to be the Velazquez painting that the Captain got painted out of, except of course in this version he’s still there. The irony about the place is that it’s so upscale the Captain himself would never have been welcome there.

Thanks again for the post.

Violette – Thanks, for the kind words, I’m glad you enjoyed the piece. And thank you for all the info. I was surprised at how popular Alatriste is. I can’t wait to get started on the next book.