Things Your Writing Teacher Never Taught You: A Look at How Peter Straub Crafts His Opening Chapters

Taking advantage of the fact that I’m not teaching this summer, I decided instead to take a course in the Fiction Program at Columbia College: Censorship and Writing. The course explores many kinds of censorship, not just the book-banning, burning, remove it from the library kinds. It includes self-censorship, social censorship, and censorship in the news, among others. Last week, one of our assignments was to write an essay about something we had learned about writing from reading another author. I chose to look at how Peter Straub crafts a rich and complex opening chapter, looking especially close at the beginning of his novel The Hellfire Club. With my blog deadline looming, I decided it would be equally appropriate to share it with you.

Taking advantage of the fact that I’m not teaching this summer, I decided instead to take a course in the Fiction Program at Columbia College: Censorship and Writing. The course explores many kinds of censorship, not just the book-banning, burning, remove it from the library kinds. It includes self-censorship, social censorship, and censorship in the news, among others. Last week, one of our assignments was to write an essay about something we had learned about writing from reading another author. I chose to look at how Peter Straub crafts a rich and complex opening chapter, looking especially close at the beginning of his novel The Hellfire Club. With my blog deadline looming, I decided it would be equally appropriate to share it with you.

Lessons from Peter Straub’s Fiction

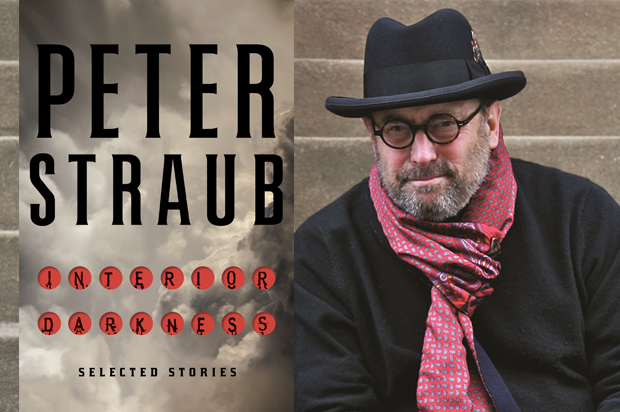

Peter Straub is an international best-seller of dark fantasy, horror, thriller, and mystery works. But he’s also a damned-fine writer, which is probably why he isn’t as big a household-known name as Stephen King, but also why his writing is more revered and studied.

From Straub I learned that commercial genre fiction can blend literary techniques, lyricism, and narrative grace with fantasy and horror tropes and mystery and thriller structure to produce work that is pleasing, popular, and thoughtful.

He is also a master of what I call the Story Promise, which is literally the promises made to the reader in the first few graphs, the first few pages, about what to expect from the story.

That would include either the overt statement or occurrence or the foreshadowing of nearly all of the following elements:

1. protagonist

2. tone

3. commercial genre and sub-genre

4. fantasy element (monsters, creatures, entities, magic, etc)

5. setting

6. time period

7. conflict

8. theme/s

and sometimes:

9. antagonist

10. side-kick

11. characterization aspects of any or all characters introduced in the first scene.

Straub’s work is often mentioned in the same breath as Stephen King’s and Dean Koontz. But I would argue that while King and Koontz are absolute masters of the Horror and Thriller genres, neither of them have the deft hand at lyrical prose and literary techniques, or nearly as true an ear for writing multi-generational casts. These talents raise Straub’s work above most of the commercial best-sellers.

Part of this comes from being highly-educated, well-read in world literature, and having done some ex-pat time in France as a young writer.

In the page and a half opening chapter of The Hellfire Club, Straub blends fairytale aspects with the structure of the opening chapter of a Who Dunnit mystery, to create a unique and compelling Story Promise that sinks multiple hooks deep into the reader.

Let me borrow the essential line from Amazon.com for the book description: “…the history of a famous fantasy novel not only concerns some eccentric authors, but collides with a wily killer on a rampage.”

The opening sequence of the novel starts like this:

SHORELANDS, JULY 1938

An uncertain Agnes Brotherhood brought her mop, bucket, and carpet sweeper to the door of Gingerbread at nine-thirty in the morning, by which hour its only resident, the poet Katherine Mannheim, should have been dispatching a breakfast of dry toast and strong tea in the ground-floor kitchen.

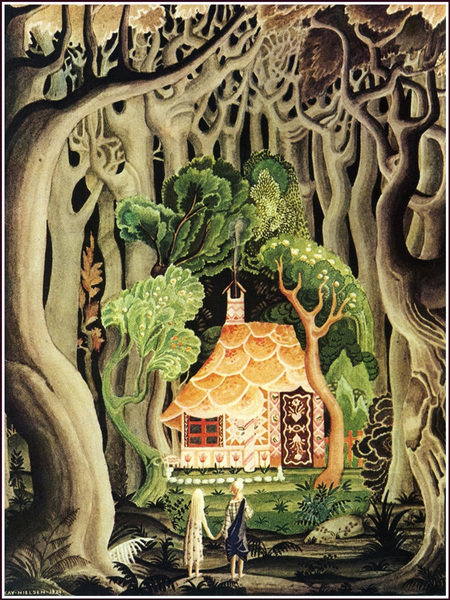

Straub gets basic geography and time quickly out of the way with a header, so he can start a masterful blending of fairytale and police procedural/mystery elements. By calling the cottage (at a writers retreat — which we’ll find out a little later) simply Gingerbread, rather than saying, “The cottage named Gingerbread at the writers retreat out on the Shorelands…” immediately invokes the feel of a famous German fairytale. By detailing that Agnes is carrying all those cleaning implements, he continues the fairytale feel — this is Gretel cleaning the Gingerbread cottage after the witch has caught her and her brother Hansel; and we can’t help think about Cinderella, whose name comes from having to sweep up the cinders in the fireplace in her step-mother’s home. Agnes could easily be a fictitious character created by the poet Katherine Mannheim.

But the paragraph’s not all fairytale, we get a strict time code: 9:30; a statement of how many people live there, what the resident’s full name is, what her normal habits were, the fact that the kitchen is situated on the ground floor — all things an officer would include in a police report. That police report feel is heightened by the next line of the paragraph:

Agnes selected a key from the thick bunch looped to her waist, pushed it into the door, and the unlocked door swung open by itself.

An officer would very much want to know that she is one of only a few people who has easy entrance to any locked cottage in the community, and that the witness/person of interest reports that the cottage was unlocked.

The next graph is basically a witness statement of/for Agnes, describing what she did and what she saw in that cottage.

The third graph takes us back to the fairytale feel:

On her way to Rapunzel and its two terrible occupants, one a penniless ferret, the other a pitted bull toad with wandering hands, Agnes ignored a Shorelands commandment and left Gingerbread’s door unlocked.

This cottage is also given a fairytale name. While it’s named for the imprisoned inhabitant of a tall tower, her name is more immediately evocative of the German fairytale than “the tall tower where Rapunzel’s step-mother/witch locked her in to keep her safe from men.” Rapunzel was of course “freed” when an adventuring prince, lured by her lovely singing voice night after night, convinces her to let down her long hair so he might climb up.

Does the prince not have access to rope and iron hooks??? Why has he no interest in bringing a rope or rope ladder back to rescue her from the tower, take her back to his kingdom, and wed her? He treated the tower and its trapped inhabitant like a high — if not high-class — whorehouse at best, and treated Rapunzel like a sex-slave, at worst. He gets her pregnant; the witch finds out; cuts Rapunzel’s hair, casts the pregnant girl into the wilderness; tricks the prince into climbing the tower that night; then pushes him off where he falls and is blinded by thorns. Knowing that fairytale, it is more than appropriate to make that cottage’s inhabitant include a man with wandering hands.

Straub brings additional fairytale and fantasy connections to the passage by describing the two men as a ferret and a pitted bull toad. There is a children’s book series about Frog and Toad as friends, and with a ferret and a toad, one is also reminded of the utterly charming children’s classic, The Wind in the Willows. We can assume, for now, that this is foreshadowing of the more extensive characteristics and characterization of the ferret and pitted bull toad men.

Lest we forget the dual purpose of the Story Promise, that paragraph ends with a critical piece of info for the police: the door of the Gingerbread was left unlocked.

The fourth, longer graph, introduces additional characters and suspects for the mystery, this time Mr. Austryn Fain and his cottage, Pepper Pot, named, I assume, for the female character Mrs. Pepperpot, the protagonist of numerous Norwegian folk tales. Normally a normal-sized woman, Pepper is able to shrink her size down to the height of a Pepper Pot (pepper shaker), and in that form, has the ability to converse with animals. (Highly useful, given the ferret and toad in the neighboring cottage.)

In the next graph, we have the hostess of the retreat introduced, and all the (potential) suspects gathered at a dinner party (a classic mystery trope). They form a search party, and go to Gingerbread. They search it high and low, and find only a few small personal items, some of which are damaged, and will undoubtedly be clues.

And in the last graph, a final hook, blending the fairytale and the thriller genres, is sunk deep into the reader’s mind:

No manuscript complete or incomplete was ever found, nor were any notes. Agnes Brotherhood never spoke of her misgivings until the early 1990s, when a murder and a kidnaped woman were escorted into her invalid’s room on the second floor of Main House.

I have no doubt that each of the characters’ names and other details included in this opening chapter have literary allusions that I don’t recognize, and bring an even deeper richness to the writing, and provide additional clues and foreshadowing, to readers who do.

I have read at least ten of Peter Straub’s novels and two collections of his short stories. He is the master of writing opening chapters that can often virtually stand alone as a fable or fairytale, but which perfectly encapsulates the themes and structure of the story that is to come.

It came as no surprise when he told me once that the published first chapter is always the last thing he writes. He explained, “I can’t write my first chapter until I’m absolutely sure I know what the book is about.”

Tina L. Jens has been teaching varying combinations of Exploring Fantasy Genre Writing, Fantasy Writing Workshop, and Advanced Fantasy Writing Workshop at Columbia College-Chicago since 2007. The first of her 75 or so published fantasy and horror short stories was released in 1994. She has had dozens of newspaper articles published, a few poems, a comic, and had a short comedic play produced in Alabama and another chosen for a table reading by Dandelion Theatre in Chicago. Her novel, The Blues Ain’t Nothin’: Tales of the Lonesome Blues Pub, won Best Novel from the National Federation of Press Women, and was a final nominee for Best First Novel for the Bram Stoker and International Horror Guild awards.

She was the senior producer of a weekly fiction reading series, Twilight Tales, for 15 years, and was the editor/publisher of the Twilight Tales small press, overseeing 26 anthologies and collections. She co-chaired a World Fantasy Convention, a World Horror Convention, and served for two years as the Chairman of the Board for the Horror Writers Assoc. Along with teaching, writing, and blogging, she also supervises a revolving crew of interns who help her run the monthly, multi-genre, reading series Gumbo Fiction Salon in Chicago. You can find more of her musings on writing, social justice, politics, and feminism on Facebook @ Tina Jens. Be sure to drop her a PM and tell her you saw her Black Gate blog.

Well, I disagree with your assessment of King, who is also a “damn fine writer,” and I’ll note that critics writing for the somewhat hoity-toity Washington Post and New York Times have seemed to agree with me for decades as well, but Straub is also a long-time favorite.

I consider “Shadowland” to be brilliant, in structure, plot, characterization, and, as you call it “narrative grace.” But my favorite is probably “Mystery,” the middle of the Blue Rose trilogy, probably because Straub does such a good job of evoking an eerie feeling in the first several chapters, before one fully knows what’s going on.

That said, I’ve come to realize that, at least in his earlier novels, Straub is or was not that great at writing female characters, or let’s just say that the ones in “Mystery” and in “Shadowland” would come nowhere near passing the Bechdel test. 😉 That at least is one place where King is a far better writer, and has been since his early days.

Note, I also like Koontz, but would agree that his writing is somewhat pedestrian (even though his plotting is often quite good). I do think his writing has gotten better over the years, as have both King and Straub.

Being a horror fiction lover, I’m not sure I can get behind Koontz being called a master of horror. He’s popular, but he’s no master. There isn’t, IMO, a single work he’ll be remembered for.