After the Twilight: Walt Simonson’s Ragnarök

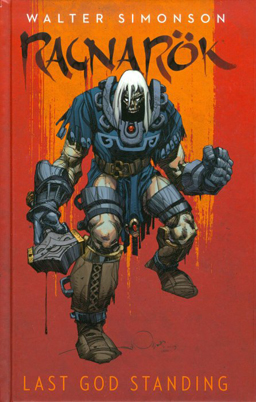

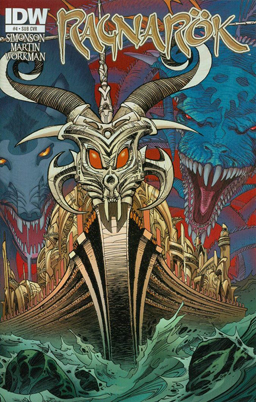

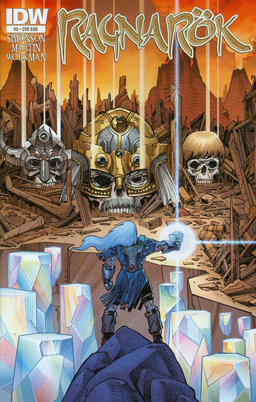

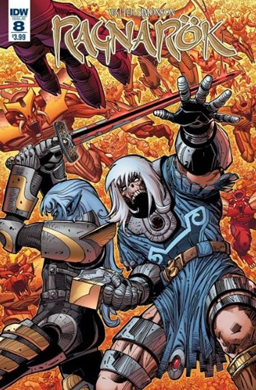

Walt Simonson’s published eight issues so far of his ongoing comics series Ragnarök, along with a trade paperback collecting issues 1 through 6. Simonson, a veteran master of the comics form, is joined for the book by colorist Laura Martin and letterer John Workman. Edited by Scott Dunbier, Ragnarök’s published through IDW, and Chris Mowry’s credited with “production” on the first seven issues while Neil Uyetake gets the production credit on the eighth. What is Ragnarök beyond that? A fast-paced, adventurous saga. A grim playing-about with Norse myth. A super-hero high fantasy that nods to the past while telling a new and distinctive tale. And: a comic as exuberant as it is well-crafted.

Walt Simonson’s published eight issues so far of his ongoing comics series Ragnarök, along with a trade paperback collecting issues 1 through 6. Simonson, a veteran master of the comics form, is joined for the book by colorist Laura Martin and letterer John Workman. Edited by Scott Dunbier, Ragnarök’s published through IDW, and Chris Mowry’s credited with “production” on the first seven issues while Neil Uyetake gets the production credit on the eighth. What is Ragnarök beyond that? A fast-paced, adventurous saga. A grim playing-about with Norse myth. A super-hero high fantasy that nods to the past while telling a new and distinctive tale. And: a comic as exuberant as it is well-crafted.

The Viking legends say that at the end of time the heroic gods battle the assembled forces of evil, lose, and the fire giant Surtur destroys the world. Simonson’s imagined a story that takes place after the great final battle, but before the burning of the earth. In Ragnarök years have passed since the defeat of the gods. Then a mysterious figure hires a family of black elf assassins to kill a dead god. Things go wrong, and that god, a very familiar god who wields an unstoppable warhammer, instead awakens. Alone in a world ruled by his enemies, the zombie-like god that once was Thor seeks divine vengeance.

Difficult, in talking about this book, not to talk about Simonson’s stunning work in the 1980s on Marvel Comics’ version of Thor, one of the greatest post–Jack Kirby runs on any book in Marvel’s history. After having drawn some issues of the book a few years previously, he took over as both writer and artist with issue 337 and began a long-ranging story that finally ended in issue 382 (he’d given up art duties a bit more than a year before). Simonson brought a new awareness of myth to the book, and a striking design sense grounded in Norse culture as interpreted through a Kirbyesque lens. He also brought a powerful grasp of comics craft and storytelling technique.

A fan-favorite artist of the 1970s, having risen to prominence at DC as the artist on the Manhunter serial written by Archie Goodwin, Simonson always had a strong sense of page and panel design. That lent itself not just to bravura displays of technique, but to powerful storytelling — and in Ragnarök too you can still see the tight narrative, the depth of character revealed through action, the ability to imply much in an image or phrase or the way image and phrase play off each other. You can see the dynamic compositions, too. Put another way: you can see the collected lessons of a career in comics at work in Ragnarök.

A fan-favorite artist of the 1970s, having risen to prominence at DC as the artist on the Manhunter serial written by Archie Goodwin, Simonson always had a strong sense of page and panel design. That lent itself not just to bravura displays of technique, but to powerful storytelling — and in Ragnarök too you can still see the tight narrative, the depth of character revealed through action, the ability to imply much in an image or phrase or the way image and phrase play off each other. You can see the dynamic compositions, too. Put another way: you can see the collected lessons of a career in comics at work in Ragnarök.

And yet the book feels new. Yes, Simonson’s got experience working with these myths, and perhaps (so far) it’s tempting to imagine this series as a distant sequel to his Marvel run. But the tone is different. Gloomier, perhaps, which is appropriate for a story that takes place after the twilight of the Gods. Then again, even in his Marvel work Simonson’s writing played with the doom promised by Norse legends. He knew that heroism was impossible without real consequences. He wrote deeply moving stories about last stands and aged warriors. Tonally, Ragnarök feels a little like an expansion of his storyline about Eilif, the Last Viking (The Mighty Thor 342 and 343). The sense of loss is similar, and the sense of passing time balanced with immortal legendry. What remains? What passes away? How to mourn what is lost, and how to celebrate a fit ending?

(Perhaps also worth mentioning another point about the 80s Thor run: Simonson did a piece of artwork for Marvel’s promotional book Marvel Age that teased an upcoming storyline called “The Saga of the Vengeance of Thor,” in which Asgard lost a war to the evil giants, leaving only Thor and a few allies to fight back. Simonson didn’t end up telling that story before leaving the book. In a sense, he’s finally getting around to telling a similar story now.)

At the same time, while there are passages in Ragnarök that are elegaic it doesn’t read to me as nostalgic. There’s no yearning for the past. What’s happened has happened. The characters still living are dealing with the world as it is, and still find reasons to look forward to the future. There’s still good, even after evil wins. There may even be reason for hope.

At the same time, while there are passages in Ragnarök that are elegaic it doesn’t read to me as nostalgic. There’s no yearning for the past. What’s happened has happened. The characters still living are dealing with the world as it is, and still find reasons to look forward to the future. There’s still good, even after evil wins. There may even be reason for hope.

Given the set-up of the world — the Gods are dead! Evil has won! — you might expect this to be either what super-hero fans used to call “grim’n’gritty,” or what fantasy fans today call “grimdark.” But it’s neither. The scale’s too grand for the first, the epic too much a part of the tale. And there’s a sense of joy to the book, however subliminal, that doesn’t fit with the second. It’s a subtextual joy, if you like, but it’s there. The characters have a zest for living and fighting. It is, in a sense, a reproof to much grimdark writing: particularly in the elven assassins, Simonson’s writing characters who’ve lived through the worst but consciously or unconsciously refuse to let it define them. People who refuse to let “the worst” limit the choices they make for their future and their children’s future. Bad things happen, sacrifices and self-sacrifice must be made, but life and ideals persist.

One might wonder if the story’s overly traditional, in fact. The dead god at the heart of the story is a lone warrior trying at first to understand what’s happened to him, then seeking revenge for the death of everyone he cared for. That’s not the most unconventional story-shape in the world. I’d argue that the way the story plays with familiar elements makes it new: the way it fits old legends into unaccustomed shapes. Of course, Simonson tells his story using traditional comics devices — sound effects, thought balloons, exposition spoken aloud. Operatic, they create a larger-than-life sense that works with the adventure-story feel of the book. Old techniques; but made new.

Certainly the panel-to-panel storytelling is classically dramatic. Simonson’s maybe the closest living creator to Jack Kirby not just in the formal dexterity with which he tells adventure tales, and not just in the powerful staging he brings to his fight scenes, but in his unironic yet thoroughly effective embrace of a kind of amplified storytelling: characters flung through the air by a punch, establishing shots that diminish characters to specks, panels framed by a chaos of outflung limbs or jumping feet. Ragnarök is more than a collection of fight scenes, and Simonson does vary his storytelling approach to fit the tone of the scenes, but I still find a wonderful extravagance in the book. It’s a stunning performance.

Certainly the panel-to-panel storytelling is classically dramatic. Simonson’s maybe the closest living creator to Jack Kirby not just in the formal dexterity with which he tells adventure tales, and not just in the powerful staging he brings to his fight scenes, but in his unironic yet thoroughly effective embrace of a kind of amplified storytelling: characters flung through the air by a punch, establishing shots that diminish characters to specks, panels framed by a chaos of outflung limbs or jumping feet. Ragnarök is more than a collection of fight scenes, and Simonson does vary his storytelling approach to fit the tone of the scenes, but I still find a wonderful extravagance in the book. It’s a stunning performance.

John Workman and Laura Martin do their part. Workman’s a frequent collaborator of Simonson, and his familiar style helps emphasise a continuity with Simonson’s earlier work; he’s also just plain good, using elegant design touches in the placement of balloons and captions. Martin, meanwhile, develops a palette that evokes the brightness and contrast of classic super-hero comics without being limited to the garishness of old colouring technology. The colours support the linework — and also convey atmosphere, as over the course of the series the dominant colours seem to grow lighter and warmer.

Simonson’s created any number of great super-hero stories over the years, and has had an awful lot to say about the nature of heroism, about its limits and about a hero’s ability to inspire. I can’t help but think of his run on Orion from 2000 to 2002, just as powerful and inventive an investigation of a Kirby character as was his run on Thor. Like Ragnarök it pushed the character into new areas by moving past the point most people assumed would be an ending. Like Ragnarök promises to, it challenged the character and the readers to work out what a hero really was when all the narrative rules were different. Ragnarök’s an investigation of familiar themes, then, but also an advance. At least so far, the audience is kept at a further remove from the characters. We’re in an unfamiliar world. Nothing’s certain. Of course; the gods are dead.

It’s tempting to imagine Ragnarök as some sort of Dark Knight Returns for Simonson’s earlier version of Thor. Also tempting to imagine it as a response to Marvel Zombies, showing what a bit of imagination could bring to the idea of an undead god. But it’s more than either of these things. Simonson, like Kirby, fuses technology and myth into high adventure; here, he’s doing it with a post-apocalyptic sensibility as well. There’s an autumnal feel to Ragnarök, almost something like Vance’s Dying Earth. As I read it, it’s a book about the acidity of passing time, about the way the things you think will last forever get worn down. But also a story about living on, about new things springing up that you never expected. It’s a story about trying to protect the young from the wars of the old. It’s a story of gods that sets a middle course between horror and wonder. So it is, indeed, a super-hero story; more than that, it is the closest thing I’ve ever read to an old man’s super-hero story. And it works, because it shows that hope and adventure do not need to die so long as life endures.

It’s tempting to imagine Ragnarök as some sort of Dark Knight Returns for Simonson’s earlier version of Thor. Also tempting to imagine it as a response to Marvel Zombies, showing what a bit of imagination could bring to the idea of an undead god. But it’s more than either of these things. Simonson, like Kirby, fuses technology and myth into high adventure; here, he’s doing it with a post-apocalyptic sensibility as well. There’s an autumnal feel to Ragnarök, almost something like Vance’s Dying Earth. As I read it, it’s a book about the acidity of passing time, about the way the things you think will last forever get worn down. But also a story about living on, about new things springing up that you never expected. It’s a story about trying to protect the young from the wars of the old. It’s a story of gods that sets a middle course between horror and wonder. So it is, indeed, a super-hero story; more than that, it is the closest thing I’ve ever read to an old man’s super-hero story. And it works, because it shows that hope and adventure do not need to die so long as life endures.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy a collection of his essays for Black Gate, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Great article! I always love seeing more comic book reviews on black gate.

I read Simonson’s Thor run last year when I subscribed to Marvel Unlimited. The first three quarters was just as good as everyone says it is. It kind of loses its way towards the end.

I’ve been look at buying the Ragnarok trade since the first issue. I held back because it did look like just another grimdark series, usually that stuff is only good for one read. If I can find a deal on the first trade paperback I’ll probably pick it up.

I have a collection of Simonson’s Thor called “Thor Visionaries Walt Simonson”. It was an awesome read. I’m definitely going to be getting this in tpb. Great article, that last paragraph made me wonder if Simonson getting older himself had a hand in the story’s narrative.

Hey Glenn,

It begins to wander at about the point that the Judge Dredd clone from the future appears, but I thought it picked back up in the final issues, bringing his run to a satisfying close.

There was one filler issue that isn’t in the collection, written and illustrated by someone else, whose name escapes me (and it’s in a box in the basement, so I can’t check). But I really wish it had been included. It’s a wonderful tall tale spun by Hercules about a fight he had with Thor. As I have all the trade paperbacks now I’ll be selling off the comics, but not that one…

Howard, that is Thor #356. From what i understand Simonson had trouble meeting his deadline so they put out a filler issue that ended up being pretty funny.

The writier is Bob Harras and the penciller is Bob Layton (none of this info is from memory.)

Thanks, Glenn and CMR!

You know, this is all getting me in the mood to reread Simonson’s Thor again.