Joseph P Laycock’s Dangerous Games: Revisiting the “Moral” Panic Around D&D (and You Thought the ‘Pups Were Bad)

The 80s Dungeons and Dragons Moral Panic gave my teenage AD&D group a headache… fortunately, only literally.

I confess that we drank too much beer while watching the movie Mazes and Monsters. We giggled at the odd (willful?) misrepresentation of our world, but perhaps that was a kind of false bravado because we also talked too late into the night: “Did they just…?” and “Erk?” and “WTF?”

And so, as is the way of things, we woke up without answers to those questions, but with headaches — or at least I did.

I now know that we were lucky growing up in cosmopolitan, largely secularist, middle class Edinburgh.

Scratch the Internet (e.g.) and you’ll uncover heartbreaking stories of teenagers — even outside the USA — thrown into needless conflict with their parents, and parents duped into betrayals that can’t be fixed: imagine coming home to find your lovingly created campaign world, months of work, had been burned?*

*You’ll also get a reminder that the entire United States wasn’t consumed by this latter-day witch hunt. If you guys gave us the panic, you also gave us D&D in the first place. Plus Rock and Roll and jeans. Thanks!

And when you read these heartrending accounts, you come back to the questions, “Did they just…?” and “Erk?” and “WTF?”, more or less my 12-year-old-son’s response when he heard about all this on a podcast.

Which brings us to the subject of that podcast: Joseph P Laycock’s book, Dangerous Games: What the Moral Panic over Role-Playing Games Says about Play, Religion, and Imagined Worlds.

Laycock is like a Call of Cthulhu character: a card-carrying theology professor who has set out to investigate the forces of darkness so we don’t have to.

In other words, Laycock has studied the awful anti-gaming propaganda, digested it, and made some kind of sense of the whole mess by ransacking theology, sociology, anthropology and philosophy for answers.

The end result is a little mindblowing, not least because he has gone beyond “Why did these odd people beat on roleplayers?” through “Why roleplaying… no really, why?” to “Why and what is play?”

And it’s all nailed down with references and citations.

Because, yes, this is an academic book. He throws around technical terms you’re supposed to know — sui generis anybody? — cites the likes of Huizinga, and doesn’t pad or illuminate with anecdotes and reportage. However, nor does he feel the need to make ritual abeyance to fashionable theories.

He’s also a very clear academic writer of the kind Stephen Pinker would approve. This is a specialist book, but written by an adult who doesn’t need to use obscurity to impress us. Instead, we are impressed by the breadth and depth of his ideas: he’s no Malcolm Gladwell, but I wager he could be if he wanted to.

There’s a lot to this book, including a definitive history of wargaming and roleplaying, a consideration of how roleplaying games, especially from White Wolf, helped alternative and neo-pagan communities frame their beliefs and identities, and a long and fascinating discussion about the nature of “play” (which I’ll touch on below). However, the real payload is his history and analysis of the “Moral” Panic.

The “moral entrepreneurs” (his term: miaow!) driving the panic turn out to be a motley collection of dubious self-promoters and fantasists with little understanding of what Dungeons and Dragons actually was (one claimed wrongly that Jesus features in the Deities and Demigods book), a sometimes limited understanding of the Bible itself (e.g. failing to recognize Biblical material where it appeared in the gaming books), and not actually very representative of Christians as a whole… not surprising since many of the original inventors of D&D were devout Christians, as are many modern players, including one of our DMs back in the day (he and I used to argue about religion).

Among their illustrious number we find self-proclaimed reformed Satanist high priests turned preachers; a self-proclaimed “great detective” who recounts taking part in helicopter raids to rescue cult victims (aye, right as we say in Scotland); and a death-row radio-phone-in star looking for somebody else to blame.

We also get more tragic figures: parents trying to make sense of teenage suicide, finding it easier to blame the Players Handbook than more obvious and upsetting factors. (And actually, in the suicide statistics these people cite, D&D playing teenagers are underrepresented. Just think about that for a moment if you think the panic was pretty harmless.) Almost all of them can be shown to have lied about their past in substantive ways (no, really?).

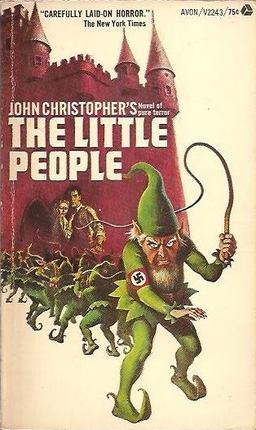

Laycock shows how these “moral entrepreneurs” insisted on treating the game literally and taking elements out of context, and how they willfully served up a dreary double-bind: where the game reflected the Christian worldview of its creators (yes, really) this was blasphemy or “authentic” demonism, but where it ignored the Judaeo-Christian tradition, it was excluding God. It turns out they didn’t like imagination very much, let alone Fantasy (unless it was written by Tolkien or CS Lewis who were certified Christians). He suggests that the truth is that their particular brand of literalistic religion felt threatened by any exercise that encouraged people to imagine other cosmologies.

Throughout, the Witchfinder General’s moral hazard comes across very clearly indeed.

Teenage gamers in pre-Internet years were a pretty vulnerable lot. It was easy to beat on them because they couldn’t mount any sort of practical or rhetorical defense, and beating on them was a great way to acquire status and wealth since parents, thanks to long hours and yawning generation gaps, felt increasingly marginalised from their children’s lives.

Speaking as a dad, I find it sad that time and again well-meaning parents trusted these… odd people more than they trusted their own children. I mean, in what universe is, “Hello, I am a former Vampire and Satanic Cult Leader who has experienced real magic but I found Christ and I am here to tell you that Dungeons and Dragons will teach your children to summon demons please buy my book and also pass along the donation box once you have put in your dollars” a convincing proposition?

Obviously — scarily! — in the same universe in which these “moral entrepreneurs” inserted themselves into daytime TV, serious documentaries, and — more worryingly — law enforcement and youth work through seminars, pamphlets and books that — via a process of Chinese Whispers — established supposition and fantasy as fact. Once something is a “fact,” it becomes an easy explanation. Since D&D was so successful, it was easy to link almost any troubled teenager to the game and since everybody “knew” D&D made kids go off the rails, here was yet more proof…

All that answers the “Did they just..?” but leaves us pondering the “Erk?” and “WTF?”

Fortunately, Laycock has answers for us. He gleefully — well I imagine him being gleeful as he types — points out the big elephant in the room:

Ex satanist vampires, occult investigators, blessing-wielding clerics… don’t the moral entrepreneurs look awfully like a bunch of LARPers who’ve lost touch with reality? They even share imagery and tropes with the game designers, for example drawing freely on 70s horror films.

Imaginative play — says the evidence — helps people get a better, not worse, grip on reality and morality. It’s also where new approaches and new ideas come from — one of the reasons why The Powers That Be generally try to suppress or limit it; they don’t want people to think outside the box. We’re hard-wired for this, and modern Anthropologists often treat religious thought as a form of play, albeit a very serious one indeed.

The problem occurs when people refuse to play… when they insist everything should be literal and measurably real. The fantasies don’t go away. Instead of safely playing out on paper to the sound of rattling dice, they portray their heroic fantasies in real life with unconsenting teenagers dragooned into the roles of NPCs. And condemning D&D is their only way to justify their interest in the tropes and genres it represents.

The “Moral” Panic still casts a shadow, but by the end of the 20th century people had much bigger, more real things to worry about. It will be back, though.

The SF&F community has showed itself ready to vigorously defend a yearly convention that offers joy to a few thousand adults. Will our community be just as energetic when the self-aggrandising forces of repression again set out to blight the childhoods of tens of thousands of teenagers?

M Harold Page is the sword-wielding author of works such as Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”). For his take on writing, read Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)

Ah, I can fondly remember the moral panic of D&D back in the 80s. I felt like such an outlaw! Things were a bit awkward when a local kid (Sean Sellers- very likely the death-row-inmate mentioned above) murdered his parents.

Anyway, the whole D&D occult thing was so ridicules on its face that I never took it seriously. BUT I remember this one time, when I was adding up experience points from that night’s game and I was using the Appendix E from the DM’s Guide (because it summarizes the base experience plus the experience per hit point of each monster).

The party had beaten a Type VI demon, and I had to admit that I gave a little start when I noticed that, while the Monster Manuel mentions there are only six such creatures known to exist, the DM’s guide Appendix E LISTS THE NAMES OF ALL SIX!

Anyway, I wasn’t like totally freaked out or anything, I just figured that Gygax and company had just made them up, or mined them from Sumerian mythology or something.

Prof. Laycock’s book sounds like a great addition to the sociological study of leisure, akin to Prof. Gary Fine’s Shared Fantasy, a study of the sub-culture of roleplaying, with emphasis on the games played by his faculty colleague at Univ. of Minnesota, M.A.R. Barker.

And we US roleplayers got off lightly in terms of the 1980s “moral panic” backlash. For true horror, see the “Satanic panic” that engulfed child day-care facilities, where teachers and staff were sent to prison for allegedly abusing the children by forced participation in Satanic rituals, blood drinking, animal sacrifice, travel via hidden tunnels, coprophagy, and other less credible offenses. A comparison to the 1692-1693 Salem Witch Trials is not out of place.

Thanks for linking to that podcast. It made an interesting pairing with the Science Friday podcast I listened to earlier today, which had a segment on children and their imaginary friends. (The kids could get a little concerned if the psychologist appeared to believe in their imaginary friends. “You know it’s pretend, right?”)

@ Eugene R.

Laycock does cover the Satanic panic and the anatomy of a moral panic; I didn’t have space to cover that in the review and perhaps didn’t want to go there in the article.

Certainly more awful things have happened and do happen. Ultimately, like Puppygate, it’s all a First World Problem anyway.

However, I think it is worth noticing and resisting what’s essentially a wide-spread epidemic of bad parenting and bad governance, not to mention rights violation.

Role playing games have mainstreamed so much over the past few decades that the extremes of some of the initial cultural reaction to them must seem bizarre to those who’ve come of age with them.

I was a DM for my high school friends. When I tried to set up a game with some friends I made in college, one of them was disappointed, and a little relieved, that game would not entail taking massive doses of drugs and going down into the sewer. This was a smart, socially aware guy, but all he’d learned of D&D was what mainstream pop culture had fed him.

Thanks for this review. In your opinion, does Laylock make a straw-man out of this anti-D&D view? The reason I ask is that it seems fairly simple to argue against this view. Is there absolutely nothing of substance to the opposition?

> does Laycock make a straw-man out of this anti-D&D view?

I don’t think he makes a straw man out of it, so much as holds it up to the light.

> Is there absolutely nothing of substance to the opposition?

Ah, that’s a difficult one. It’s certainly clear – and he says this in his book – that certain (what I would term) authoritarian literalistic flavours of Christianity are threatened by Fantasy in general and FRPGs in particular because of the way FRPGs encourage you to explore other cosmologies and make them work.

It’s also fairly clear, again from his book and anecdotally, that *that* exploration can potentially take you to less mainstream beliefs in real life. However these beliefs are generally not in harmful in the mundane sense – e.g. the pagans and wiccans I know seem perfectly happy and well adjusted and don’t go around killing people or themselves.

So it depends where you stand on issues like freedom of choice of religion, and the existence of Hell and what gets you there. Also whether the religion you’ve taught your kids will fall apart as soon as they look at it from the outside – I myself strongly suspect that the fiercer and louder the faith, the more likely kids are to rebel against it.

There are plenty of Christian gamers, and most of the originators of D&D were believers, so it certainly isn’t an instant paganisation device…

Interesting.

That was also the era of the “backwards-masking” panic, which seemed kind of inextricably linked to D&D panic, at least in terms of sheer wackiness of the panic.

> That was also the era of the “backwards-masking” panic

I learned how to play cassette tapes backward by accident. My audio recording of The Hobbit movie broke. Not a problem, as I had already learned how to patch broken tape with scotch tape. But this time I managed to twist the tape. When I hit play, Gollum delivered his riddles backward, which was not on the side I had playing and sounded all kinds of freaky. (Really? Of all the parts of that movie that could have played, it had to be “Riddles in the Dark”?)

Once I figured out what I had done, I gleefully copied Petra’s “Judas Kiss” to a cheap tape; cut, flipped, spliced; and hit play. A perfect, “What are you looking for the devil for, when you oughta be looking for the Lord.” (I already knew what it said. They had a hilarious setup for that line in their concert.)

Petra’s “Judas Kiss”! I haven’t heard that in years. I vaguely remember some sort of “baskmasking” at the beginning of that song. Are you saying that this is what it said?

James, correct. Petra was anti-backmask-hunting.

[…] Revisiting the “Moral” Panic Around D&D […]