The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: Enter Jim Chee

So, The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes has talked about Tony Hillerman here and Joe Leaphorn here. Leaphorn had featured in the first three novels: The Blessing Way, Dance Hall of the Dead and Listening Woman. This week, we turn our attention to Jim Chee

So, The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes has talked about Tony Hillerman here and Joe Leaphorn here. Leaphorn had featured in the first three novels: The Blessing Way, Dance Hall of the Dead and Listening Woman. This week, we turn our attention to Jim Chee

For his fourth Navajo Police novel, People of Darkness, Hillerman needed a less wise, less assimilated policeman. He actually considered flashing back to a younger Leaphorn but decided against that and instead created the younger, more naïve, Chee. He would hold for the next three books.

In addition to providing an alternative protagonist, Hillerman also changes the opening. In prior books, they begin outside, painting a picture of the reservation: Louis Horsman, on the run from the law, is setting traps to catch kangaroo rats (when he encounters a skinwalker – a witch). George Bowlegs is out running to practice for a Zuni religious ritual (and has a similarly unhappy encounter). And how about this descriptive passage to begin Listening Woman:

“The southwest wind picked up turbulence around the San Francisco Peaks, howled across the emptiness of the Moenkopi plateau, and made a thousand strange sounds in windows of the old Hopi villages at Shongopov and Second Mesa.”

But People of Darkness begins with somebody looking out her office window in a cancer clinic. Things certainly do get started with a bang!

Chee’s introduction is reminiscent of the opening scene of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep. We have a “common” private investigator visiting a rich client of higher social standing. Rosemary Vines wants Chee to take some leave and find a box of keepsakes stolen from her husband. Her husband says it’s all a big mistake: no worry. Hillerman mixes in the Native American Church (the ones that caused the big legal furor over using peyote in their rituals).

Of all Hillerman’s books in the series, this one is most like a private eye novel and has a bit of a Ross MacDonald feel to it, as an event from long ago hangs over the current investigation.

Colton Wolf, based on Robert Smallwood, is Hillerman’s first really compelling villain. Smallwood met with Hillerman and another reporter just before his execution. He wanted them to write about his death so that the story would be printed in newspapers all over the country. He hoped his mother, who he didn’t know, would see it and come claim his body so it wouldn’t be buried in the prison cemetery. Think about that. Hillerman built on this to great effect with Wolf. You can read Hillerman’s nonfiction short story about Smallwood, “First Lead Gasser.”

The Dark Wind opens with some Hopis finding a body on their way to a ceremonial, skin scraped off its hands and feet. Then, Jim Chee is staking out a windmill to find a vandal when a plane making a drug run crashes nearby. With the multiple crimes involved, this one is a bit more like a standard police procedural, with some arrogant DEA agents in the mix.

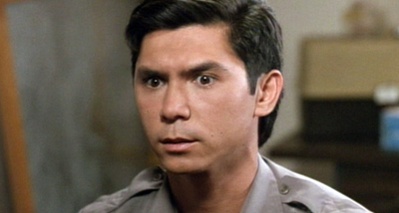

Robert Redford executive produced a movie of this book, starring Lou Diamond Phillips. The movie was shown in France and England but went straight to video in America. More on this in an upcoming movie post about the Navajo Police series. I’m not enthralled with the film, but upon repeated viewings I’ve come to like it a bit more over time.

In The Ghostway, a federal investigation into a Los Angeles car theft ring leads to the reservation. Chee himself travels to LA and he runs into Eric Vaggan, a hit man who is a racial supremacist and a survivalist. Vaggan believes the Russians are going to wipe out California with a hydrogen bomb (hey: it’s 1984) and he’ll be ready when they do. Vaggan is one of my favorite villains in the series. There’s an entire chapter devoted to how he goes about making an example of a guy who hasn’t paid his gambling debts. Oof!

Skinwalkers, the seventh novel, is primarily about Chee, but Joe Leaphorn is his superior officer in this one and the two are linked throughout the rest of the series. A third officer, Bennie Manuelito (a female), later becomes a key recurring character. In fact, Hillerman’s daughter Anne, who has written two books in the series since his death, has moved Bennie to the center.

In Seldom Disappointed, his excellent autobiography, Hillerman relates that on a book tour for The Ghostway, and old lady asked why he changed Leaphorn’s name to Chee. Stunned, he tells her they are completely different characters. She replies that she can’t tell them apart. That comment grated at him (he compared it to St. Paul’s ‘thorn in the flesh’) and he decided to put them both in the same novel. It worked and he did it again in Thief of Time. Would this seemingly inevitable pairing have happened without that little old lady? Maybe; but maybe not!

Chee is deeper, more fully fleshed out character than Leaphorn. This isn’t surprising, as Hillerman was developing his ability to write fiction and was more experienced.

Chee is deeper, more fully fleshed out character than Leaphorn. This isn’t surprising, as Hillerman was developing his ability to write fiction and was more experienced.

Chee is constantly in conflict. On a professional level, he is trying to reconcile being a policeman with becoming a singer (in Navajo, a ‘yataali’). Singers are akin to shamans, or medicine men. They perform elaborate rituals, involving complex sand paintings, that cure what ails a Navajo and brings them back into harmony and balance. There are fewer and fewer singers as the younger Navajos leave behind the old ways and Chee wants to become one. Leaphorn thinks it’s a ridiculous combination and can’t be done.

And Chee also struggles with remaining a reservation Navajo and an assimilated Navajo. There’s a dilemma in The Ghostway that typifies this. Navajos will not enter a house (or hogan) where a person died. The bad that was in the deceased (their chindi) remains trapped in the structure. And someone entering is likely to be infected by it. Chee needs to enter a death hogan and is literally stuck at the entrance, foot poised in the air to take that step. The step that could mean admitting he can live in the Anglo world and leave behind the Navajo.

This ‘assimilation’ issue is at the root of his relationship problem with Mary Landon. And it’s also a professional dilemma, as he was accepted into the FBI training program; but that would mean living in the white man’s world and going wherever they send him. Mary is a schoolteacher from Wisconsin, teaching at a reservation school. Chee wants to marry her and raise their children in the Navajo way. She wants to move into the Anglo world and give their offspring a better chance at success. Needless to say, this causes some friction in the relationship.

Something I wrote in last week’s post:

There’s something that pervades the early books and I think remains throughout the series (I’m on book seven of this re-read). Hillerman presents the dichotomy between the way white people think and Navajos think. It presents an obstacle that the Indian policemen must overcome to solve the crime.

A Navajo would never murder for gain. But that’s certainly a part of the mainstream culture. And Leaphorn and Chee have to consider this, even though it’s an alien concept to them and something they struggle to understand. Kind of a ‘Stranger in a Strange Land’ phenomenon, even though it’s usually their land.

Revenge is a key element of the first two Chee books. Here Hillerman lays out the dichotomy. To Chee, Revenge is:

“..as strange to him as the idea that somebody with money would steal had seemed to Mrs. Musket (the missing man’s mother). Someone who violated basic rules of behavior and harmed you was, by Navajo definition, ‘out of control.’ The ‘dark wind’ had entered him and destroyed his judgment. One avoided such persons, and worried about them, and was pleased if they were cured of this temporary insanity and returned again to hozro. But to Chee’s Navajo mind, the idea of punishing them would be as insane as the original act.”

In The Ghostway, Chee reflects on the Navajo practice of remaining silent and listening to the other person speak. Whereas, the white man constantly expects the listener to do more than listen: to reply. Also, standing outside a shabby nursing home, he simply cannot understand the concept of removing the elderly from their families and penning them up in group homes. It’s completely un-Navajo.

Mystery readers love to picture themselves as the protagonist in the story. A close reading of Hillerman requires such readers to rethink their frames of reference and assumptions about events. It educates the reader and immerses them more deeply in the cultures underlying the books.

Something that would be amusing if it wasn’t often nearly fatal, Chee seems to constantly not have his gun at hand when it’s needed. He finds a body on a picnic with Mary Landon and his pistol (and shotgun) are back in the truck). He doesn’t have it with him in LA. He gets better about this as the series goes on, but for a police officer, he sure seems in need of his inaccessible weapon a lot.

Something that would be amusing if it wasn’t often nearly fatal, Chee seems to constantly not have his gun at hand when it’s needed. He finds a body on a picnic with Mary Landon and his pistol (and shotgun) are back in the truck). He doesn’t have it with him in LA. He gets better about this as the series goes on, but for a police officer, he sure seems in need of his inaccessible weapon a lot.

Leaphorn thinks Chee is a bit of a screwball. Chee admires Leaphorn but is a bit scared of the legendary, non-traditional Navajo veteran. Chee often works outside of orders (to the consternation of Captain Largo, another superior) and wanders off on his own. His personal relationships will continue to remain a complex issue for several more books.

The eighth book in the series, 1988’s Thief of Time, was the first one I read (a gift from a friend). It was also the first to make The New York Times best-seller list and Hillerman terms it his breakout book. In all, Hillerman wrote eighteen books in the series (not bad considering his editor told him not to bother with the first one), with The Shape Shifter coming out in 2006.

I mentioned Fly on the Wall in my two previous posts. It was his attempt at the Great American Novel and was about a newspaper reporter working on a corruption story. It’s one of my ten favorite novels.

In 1996, again ignoring a marked lack of enthusiasm from his editor, he put Indians aside and wrote a different kind of novel. Moon Mathias, a Colorado newspaper editor, goes to Cambodia in search of the niece he didn’t know he had. Hillerman had mentally been working on a version of this tale for over three decades. It’s called Finding Moon.

In 1991, Tony Hillerman was diagnosed with cancer. For a man who had been blown up by a mine in World War II, this was not an insurmountable obstacle. He had three surgeries and lived until 2008 (he was 83).

I hope you’ve enjoyed these three posts on Mystery Writers of America Grand Master Tony Hillerman. A Facebook comment about one said that when you take away the Indian stuff, they were pedestrian mysteries. I don’t agree, but I’d also point out that’s like saying “Well, if you take all the eccentricities and deductions out of the Holmes stories, they’re not that good.”

I happen to think that Tony Hillerman was a very good mystery writer. Like just about all authors, he was a bit rough in the beginning, but he got better as he went on. And along with the police stuff and the mysteries themselves, the rich cultural texture throughout the series makes it an enjoyable, educational experience.

As I said in the first post, I recommend starting with the second book, The Dance Hall of the Dead. Then go back and read the first one, The Blessing Way (the main character is a white anthropologist – Leaphorn is in a supporting role), and continue on in order after that. This is a fine series.

Somewhere down the line, there will be a post about the four movies (and several failed attempts at such) made from these books. As well as one on The Fly on the Wall. I’m not done with Hillerman yet. And if you haven’t read all of his books, you shouldn’t be, either.

Part One – Meet Tony Hillerman

Part Two – The Navajo Sherlock Holmes

Part Three – Enter Jim Chee

You can read Bob Byrne’s ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column here at Black Gate every Monday morning.

He founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

His “The Adventure of the Parson’s Son” is included in the largest collection of new Sherlock Holmes stories ever published. Suprisingly, they even let him back in for Volume IV!

I’ve always liked Jim Chee and Hillerman making time march along in his stories.

[…] on the late, great Tony Hillerman over at BlackGate.com. You can find links to all three of them in this final post. I thoroughly enjoy his stuff and I recommend you check him out. Or at least read my […]

These are fine essays.

❤️ LOVE. Dark Winds