Cirsova and Pulp Literature

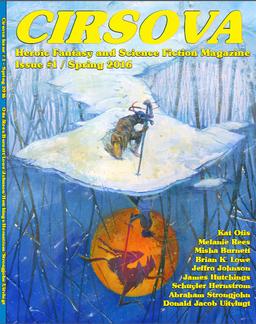

Two incredibly impressive magazines crossed my desk this past month: the very first issue of the brand new Cirsova, edited by P. Alexander, and Pulp Literature #10, edited by the triumvirate of Mel Anastasiou, Jennifer Landels, and Susan Pieters. Both are hefty collections (Cirsova is 95 pages and Pulp Literature is 229) and are available as e-books as well as real live paper versions.

Two incredibly impressive magazines crossed my desk this past month: the very first issue of the brand new Cirsova, edited by P. Alexander, and Pulp Literature #10, edited by the triumvirate of Mel Anastasiou, Jennifer Landels, and Susan Pieters. Both are hefty collections (Cirsova is 95 pages and Pulp Literature is 229) and are available as e-books as well as real live paper versions.

Unfortunately, authors and editors of sci-fi and fantasy fiction seem to want to deny the genres’ pulp roots, or to hold up their literature as worthy of being taken seriously only as it has moved away from that which led to its existence in the first place. Cirsova is a celebration of those roots. In his afterword, Alexander writes:

There are a number of reasons why I wanted to launch a Cirsova magazine, not the least of which being Jeffro Johnson’s Hugo-nominated Appendix N Retrospective series which both coincided with and helped spur my own look into a lot of older SFF stuff. Planet Stories in particular has become a favored inspiration of mine, and while I would not say that I plan or planned to model Cirsova on that particular publication, I cannot and would not deny the influence.

If that piques your interest the slightest, then Cirsova is for you.

Schuyler Hernstrom’s “The Gift of the Ob-Men” kicks off the issue. Exiled from his tribe, the young warrior Sounnu, is changed into the tool that the Ob-Men, “tall heavy creatures, bearing the form of a mushroom bent into the shape of men,” will use to reclaim their ancient homeland. They transform Sounnu, growing a third eye in his forehead that lets him see the past and more importantly, all possible futures, and turning him into a nearly unstoppable killing machine. Before he reaches his destination he will face slavering ur-wolves and a mad artist haunting a ruined city. The best individual moments are the nearly psychedelic visions the young exile has when he sees all potential futures simultaneously.

James Hutchins blatantly invokes the spirit of one of Cirsova’s guiding stars, Edgar Rice Burroughs, with his long poem, “My Name is John Carter (Part 1).” It’s a narrative poem, depicting the future Warlord of Mars as a man angry at an indifferent universe, and who finds himself drawn to a certain red planet.

Bolts of magic streak the sky and summoned flames ignite Spanish galleys in Kat Otis’ alternate history tale, “This Day, at Tilbury.” Events open on the day the Spanish Armada, supported by a complement of sorcery-wielding monks, prepares to sail up the Thames and destroy the upstart Protestant nation. Fourteen-year-old Robin Dudley, bastard son of the Earl of Leicester and possessing magical talents himself, remains with Queen Elizabeth’s tattered defenders to try and hold back the Spanish tide. Otis’ depiction of a boy thrown into the heart of powerful events has the right mix of adolescent excitement and trepidation.

The first taste of pure sword and planet comes from “At the Feet of Neptune’s Queen” by Adam Strongjohn. The newly anointed king of Mars, Ch’Or, his comrade-in-arms, Bi’Tik, and his betrothed, the warrior maiden Ra’Ana, are stolen away from their homeworld by the mighty Vraala, queen of Neptune. She desires a consort as mighty as herself and has decided Ch’Or is that man. When the Martian king rejects the queen’s entreaties, she casts him and his companions into the arena. To regain their liberty they must overcome a monstrous horror.

A grey silhouette shot across the twilit sky. The air froze about a great gob of spittle and white crystals exploded into a jagged monolith between the three Martians. The icy pillar split into shards as the massive beast landed on two fiercely taloned limbs. The Neptunians let out a thunderous cry of exuberant blood lust with fervor nearly matching the shrill emanations of the creature as it spread its bat-like wings to their full span, nearly stretching from one side of the arena to the other.

Strongjohn writes exuberant action and Neptune’s queen is a wonderfully decadent creation, but the story never clicked for me. The Martian characters never emerged enough to make me care when they where beset by betrayals.

“Rose by Any Other Name” by Brian K. Lowe reads (favorably) like a Gamma World scenario. Which means beastmen, ancient ruins, and super science. Expert in the lost understanding of the Old Machines, Kaine finds himself the rescuer of a young woman, Thorne, and the gorilla man, Balu. There’s a little mystery, a nicely limned setting, and wolverine men, so I was pretty darn happy with this story.

Melanie Rees’ choppy tale of airships and time reversal, “Late Bloom,” brings a mad steampunk vibe to the proceedings. I found the present tense prose strangely distracting, but I think I will reread it to try and get a better understanding of what the author intended.

“The Hour of the Rat” by David Jacob Uitvlugt starts as the story of Nezumi, a young servant, trying to recover some stolen property. Things change when she is surprised by a famous assassin:

Nezumi tried not to think of the stories she had heard about the White Ghost. A female assassin who was more spirit than human. Killer by night, upper-class courtesan by day. Or mistress of the shogun. Or daughter of the emperor. A demon in human form who could kill with a thought, or a touch. Nezumi suddenly realized why the three guards fell. Fuyu. She knew the name of an assassin.

What had been just an attempt to take back some hair combs becomes a bloody nightmare and demonic struggle. I’m not sure if Uitvlugt has any more stories of Nezumi or the White Ghost, but I’m very curious to know if there are.

The longest work is Misha Burnett’s fantastic, Lovecraft-inspired “A Hill of Stars.” HP Lovecraft was as much a science fiction writer as a horror writer. Even his greatest creation, Cthulhu, is not really a god, but an alien being of tremendous power. At the heart of his novella “At the Mountains of Madness” is a history of the settlement of ancient Earth by various extraterrestrial species and the creation of humans by the Old Ones.

The longest work is Misha Burnett’s fantastic, Lovecraft-inspired “A Hill of Stars.” HP Lovecraft was as much a science fiction writer as a horror writer. Even his greatest creation, Cthulhu, is not really a god, but an alien being of tremendous power. At the heart of his novella “At the Mountains of Madness” is a history of the settlement of ancient Earth by various extraterrestrial species and the creation of humans by the Old Ones.

Drawing on these specific elements of Lovecraft’s writing, Burnett posits a time between the fading of the Old Ones and the rise of humanity. Kuush Vorbus is the last human slave of Vorbus the Clement, a Great One preparing to die.

On the final day of the season of morning mists, Vorbus allowed its body to grow still and consigned its mind to the Fields Celestial. It had dwelt within the City for thirty thousand years.

Freed from the bondage he has known his entire life, and knowing the timeworn Autumn City he inhabits is running down, Kuush takes up supplies and heads out into the savage, wilds beyond its boundaries. He doesn’t know what he’ll find there, but he finds himself “filled with a savage joy at the possibilities that now beckoned from the world beyond the city walls.”

Of course, being a Mythos setting, he finds monsters — big, slimy monsters that will be familiar to many readers. He also finds human monsters who’ve found a way to reach an accord with the other ones, and turn it into a powerful advantage to use against men.

Kuush’s matter-of-fact observations and clearheaded plans reminded me of the intrepid heroes of Jack Vance’s science fiction, but Burnett is no mimic and writes in his own strong, often gorgeous, prose.

It grew darker. Darker than I had ever seen before. And then the stars came out.

In the City there is always some light. The walls along all of the major streets are painted with a soft phosphorescence. I had seen the stars, of course, looking up into the night sky, but what I had seen before was a scant handful between the walls.

Now the sky was alive with stars. The moon was absent, below the horizon or else new. Instead there were numberless points of light. My breath caught in my throat. The heavens boiled with them, a mass that seemed more solid than the unseen ground beneath me. It seemed as if I could climb that glowing mass and reach some new world with wonders unseen.

I felt very small and alone, looking up at that mass of starstuff, foothills before an unimaginable mountain range. For the first time since the death of my master I wept, not for it, but for myself, because I was very small and very alone.

Not only is this the longest story in this debut issue of Cirsova, it’s the best. It’s evident on every page that Burnett has a powerful sense of his hero and his world. Never once was I distracted during this story; I hung on each word. I already see this being on a list of my favorite stories for 2016.

Burnett’s also put out a call to authors to join him at the Eldritch Earth Geophysical Society in creating new stories for this setting. I’m hoping there are some adventurous folks willing to heed his call.

P. Alexander may say that what ties the various stories in Cirsova together is a love for the glorious pulp adventures of the past. While that is clearly true, their truest similarity lies in the authors’ love of storytelling. Too many contemporary short stories I read are nothing more than vaguely written things that do little more than create a hazy mood, or serve as a platform for a message. Like the stalwart Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, and the newer Grimdark Magazine, Cirsova has built a stage for writers to tell stories with narrative force, audacious adventure, and outlandishly magnificent settings. If this is what the first issue looks like, I expect future ones will blow me away.

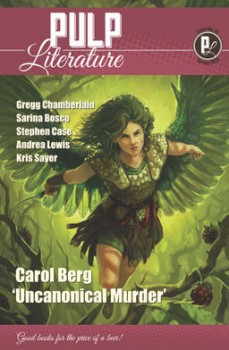

Pulp Literature has been around for several years now, having published ten thick issues. Somehow, even though I’m always on the hunt for new venues for short fiction and am always asking readers to let me know about mags I’ve missed, I must admit to my shame, I had never heard of it until one of its editors, Jennifer Landels, offered to send me a copy. While it has only a few swords & sorcery stories, I was blown away by PL’s quality and richness.

Pulp Literature has been around for several years now, having published ten thick issues. Somehow, even though I’m always on the hunt for new venues for short fiction and am always asking readers to let me know about mags I’ve missed, I must admit to my shame, I had never heard of it until one of its editors, Jennifer Landels, offered to send me a copy. While it has only a few swords & sorcery stories, I was blown away by PL’s quality and richness.

Pulp Literature, as it title implies, is a more refined publication than Cirsova. The editors’ statement explains clearly what their goal is:

We love genre. Science Fiction, Fantasy, Mystery, History, Thriller or Chiller: we read it all, as long as it’s well written.

We love literary fiction. Beautiful prose, soul-searching themes, and powerful and complex character development are all part of the stories we like.

We believe that genre fiction IS literary. Our goal is to publish writing that breaks out of the bookshelf boundaries, defies genre, surprises, and delights.

Not a bad set of goals, if you ask me. Having read this latest issue, I’m inclined to say they’ve achieved their aims.

Not only had I never encountered Pulp Literature before, I had also never heard of the author Carol Berg (even though she’s been covered here at Black Gate). Her mystery story, “Uncanonical Murder,” is set in the same world as her Collegia Magica series and is good enough to inspire me to check them out.

Hue de Paien is the constable of a small rural village who finds himself forced to uncover the murderer of an important man before the powers that be accuse and arrest him for the crime. Earlier in life his possession of unregulated magic talents left him on the wrong side the Church. He was tortured and left crippled. Only his use of highly illegal potions allows him to walk.

Berg’s world, redolent of medieval France, is populated with living, breathing characters. As the Constable made his rounds of the area — tracking down leads, questioning the residents — it’s clear the depth of thought she has brought to her creation. Her prose is clear and uncluttered. “Uncanonical Murder” is also a decent mystery, something I’ve seen too many sci-fi and fantasy writers forget to succeed at. I always love finding a writer who has stacks of books and stories I haven’t read yet. That alone made PL worth investigating.

In “Where Her Armor Was Weakest” by Kris Sayer, an encounter between a knight and her sister and a group of brigands leads to tragedy for everyone. This is a comic, not a pure prose story. While I found the art only satisfactory, the nightmare quality of the story is potent and appropriately haunting.

The last S&S tinged work in PL #10 is editor JM Landels’ “Allaigna’s Song: Overture.” It’s part of an ongoing serialized novel, recounting the adventures of twelve-year old page Allaigna, interwoven with the stories of her mother and grandmother. Not yet having read its previous sections, I struggled to follow the story. Still, I very much liked what I read, finding Allaigna, whom I very much want to revisit, possessed of strong voice and character.

The rest of Pulp Literature is filled with a wide variety of genres. Senior citizen detectives, Jewish monsters in contemporary Ontario, poetry, all sorts of good things. Don’t let that literature tag scare you off. The editors’ love of pulp in so many varieties means they have a love of storytelling and don’t neglect it. How such a magazine has escaped wider notice eludes me.

So now I’ve got two new magazines to spend my money and time on. Cirsova is still finding its footing, seeking authors who resonate with its mission and influences, but it’s already well down a road I’m bound to follow with it. Pulp Literature reminds me of Michael Chabon’s undertaking to revitalize contemporary literary writing with plot and narrative — which I completely appreciate and love. So, yeah, there’re two more players out there, supplying our regular short fiction needs. Check ’em out, and then let me (and them) know what you think.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him. You can read the last short story roundup here.

[…] Check it out here! […]

[…] of 0ver 100 posts in April, Black Gate’s review of Cirsova #1 was their 13th most popular. We’re worth talking about! Just […]

[…] we saw them, with Issue #1back in April, I wrote “If this is what the first issue looks like, I expect future ones will blow me away.” […]