Sci-ficionados: Our Insatiable Hunger for Stories, and What it Means for the Human Race

Fans of science fiction and fantasy tend to have an innate curiosity, one that is not sated simply by day-to-day life and the world as it is. They cannot content themselves with the rote script written for them.

Fans of science fiction and fantasy tend to have an innate curiosity, one that is not sated simply by day-to-day life and the world as it is. They cannot content themselves with the rote script written for them.

There are people all around who are content simply to go to school, get a job, have a family, raise kids to follow the same formula, retire. And some of these people are well informed — they read the news to see what’s going on. They have hobbies. They like to be entertained — they watch sitcoms to have a laugh at the status quo. They may even watch some of those movies with zombies and giant robots and superheroes to let a little bit of their imagination off the leash: what if this predictable old world were shaken up by something like that?

But the real sci-ficionados, they aren’t content with an occasional, half-winking excursion into the game of what-if before settling back down onto the landing pad of Reality. Because they recognize, deep down, that this is not the only possible world, and that this so-called reality is also utterly strange. They want to know about nano-tech and parasites and the Inquisition and how and why homo sapiens developed a larger prefrontal cortex and what the hell are dreams anyway? And a hundred, a thousand, a million other things. Why is this society the way it is, and is it foreordained that we must follow this script?

This Modern Life

The things we take for granted in modern life but which only came about in the last few decades — a flash in the pan for a species that has been knocking around for roughly 50,000 years — they’re all fascinating, yes, but they represent just one story.

The things we take for granted in modern life but which only came about in the last few decades — a flash in the pan for a species that has been knocking around for roughly 50,000 years — they’re all fascinating, yes, but they represent just one story.

Here’s one routine: Pick up a briefcase; jump in the car and hit the freeway to clock in at the office; work all day at a desk; clock out; come home; give your spouse and kids a kiss; grab the remote and flip on the TV to watch The Office.

This is one life experience — one frame of reference — notable for how it came about and how it fits into the bigger picture, its role in a system of which it is one small component (or “a cog in the wheel,” a saying invariably delivered with a negative connotation). Many true sci-ficionados don’t even mind living it. They’ll take the job, have the family; the whole nine yards. But they also have to have their stories — other frames of reference — and not just as a trivial pastime to decompress before bed, as we shall see.

“All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace”

In fact, to be alive in this society and part of this system right now means that we are safer and more comfortable than any other humans who have ever lived. It may be the safest and most comfortable civilization, but — oddly enough — it is not necessarily the most satisfactory or fulfilling, as evidenced by the historically high suicide rate, or the unprecedented number of people diagnosed with depression. Maybe in past eras people were too preoccupied with survival to stop and notice they were depressed or to consider taking the life they were busting their tail so hard to preserve. Maybe.

But here’s the thing. This twenty-first-century life is only one version of reality. And we — we sci-ficionados — know that it is a recent thing, a fragile thing, a blink in time on a small planet in a small solar system in an out-of-the-way galaxy in a universe filled with more galaxies than we can even guess at. There likely are other societies, other life forms, other realities — and maybe our species will have to wait until the twenty-fifth century to come into contact with any of them. Maybe we never will.

But here’s the thing. This twenty-first-century life is only one version of reality. And we — we sci-ficionados — know that it is a recent thing, a fragile thing, a blink in time on a small planet in a small solar system in an out-of-the-way galaxy in a universe filled with more galaxies than we can even guess at. There likely are other societies, other life forms, other realities — and maybe our species will have to wait until the twenty-fifth century to come into contact with any of them. Maybe we never will.

Since odds are good it won’t happen in the century or less afforded to each of us on this planet, we feel compelled to run simulations: stories about other realities; other versions of this reality and other worlds altogether. And we hungrily devour them, adding these simulations to all the real-world experiences we are living. Some are fanciful; some are dead-serious: but all are feeding that insatiable curiosity we have.

That’s Not Realistic!

The one criticism that the critic who does not share our enthusiasm for speculation cannot validly make is this: “That’s not realistic.” Compared to what? The critic — poor, narrow-minded ape — is basing his or her measurement of “realistic” on a subset of one. In other words, if it’s not like the world that the critic knows, the critic reckons it can be dismissed.

Granted, we’ve all denigrated particular works of sci-fi on the grounds of their being unrealistic, but we mean something entirely different: they did not maintain the spell because the simulation broke down, usually because of contradictions or inconsistencies within their own imagined reality. Vampires may exist in the world of Buffy, but they don’t turn into bats — and if they suddenly do, there better be a cogent explanation for it.

Socially Awkward Basement Dwellers

It is true that sf fandom attracts socially awkward types — like the stereotypical kid who rarely ventures forth from his mom’s basement except to visit the comic-book shop — for two very obvious reasons: 1) members of fandom are more tolerant and accepting than most other cliques and 2) if you feel like a misfit in this world, of course the prospect of spending a great deal of time in made-up ones is going to hold a powerful appeal.

But what most “outsiders” don’t get, and are very surprised to learn, is that this community is one of the most diverse the world has ever seen. In addition to socially maladjusted teenagers there are doctors, lawyers, entertainers — Stephen Colbert is anything but socially inept. Some of the most intelligent people I’ve ever had the pleasure to know I met within this community. Smart people. People who share the insatiable curiosity.

What Good is Never-Neverland?

Let’s cede the floor again, for just a sec, to the anti-sf critic: “So you want more stories — more, apparently, than all the stories this actual world generates every day. Fine. To what end? What good are all these Never-Neverland tales clogging up your brain? Wouldn’t you actually be better served by stories that more closely correspond to the world you actually have to compete in? If you’re going to role-play, how about a game where you try to become the CEO of a tech start-up? How about stories that better enable you to cope in this world, instead of ones that seem to provide an escape from it?”

Well, there are a few different ways to address those questions, but here I mainly want to dispel one common misapprehension: the false notion that most sci-fi geeks just don’t get how the world works, that they’re off in their own little worlds and so out of touch. First, we might just mention that a significant number of CEOs of today’s cutting-edge tech companies grew up playing Dungeons and Dragons and geeking out on Star Trek or Star Wars; apparently, the fact that they weren’t role-playing becoming a CEO of a real company did not hinder them — and their ability to think “outside the box” and from a more detached perspective seems to be a common trait in their favor in reimagining what is possible, what can be done in this world.

Well, there are a few different ways to address those questions, but here I mainly want to dispel one common misapprehension: the false notion that most sci-fi geeks just don’t get how the world works, that they’re off in their own little worlds and so out of touch. First, we might just mention that a significant number of CEOs of today’s cutting-edge tech companies grew up playing Dungeons and Dragons and geeking out on Star Trek or Star Wars; apparently, the fact that they weren’t role-playing becoming a CEO of a real company did not hinder them — and their ability to think “outside the box” and from a more detached perspective seems to be a common trait in their favor in reimagining what is possible, what can be done in this world.

But if you think all of us are naïve, I suggest you take a look at some of our bookshelves. You will find that those who possess this deep-burning curiosity are well read in far more than fantasy and science fiction. You will find in-depth works of history, philosophy, politics, religions, social sciences — you name it. You will find books on the rise and fall of civilizations, books on the latest findings in neuroscience and new theories of physics. I would go so far as to say that many sci-ficionados are better informed about this world than most people who are content with just this world. I say that anecdotally — based on my own personal experience and observations — but I believe that serious research data would support that claim (and it would likely be a sci-ficionado who’d be capable of collecting such data and making scientific sense of it).

This is Your Brain on Sci-Fi

“Okay, fine. Still — ” that stubborn critic circles back again, “wouldn’t your mind be better served if you held it just to the real stuff and did not divert so much of its attention to aliens and bugaboos and, and krampuses, or whatever?”

Here we might begin by considering on what basis does the critic privilege the stories set closer to home? It is true that our curiosity about this world will never be sated, so why waste any of our finite time on events we know did not happen and things that do not exist?

The Puritans notoriously had a version of this outlook, taken to its extreme: they condemned all fiction. The Bible was what one should mainly stick with, along with just enough non-fiction to understand the basic timeline of human history and how mankind has gone wrong and rejected the ways of the Lord. How-to manuals for developing utilitarian skills. Some martyrs’ stories (only true ones, naturally). Oh, and some poetry is okay for the missus, as long as it’s devotional in nature.

The Puritans notoriously had a version of this outlook, taken to its extreme: they condemned all fiction. The Bible was what one should mainly stick with, along with just enough non-fiction to understand the basic timeline of human history and how mankind has gone wrong and rejected the ways of the Lord. How-to manuals for developing utilitarian skills. Some martyrs’ stories (only true ones, naturally). Oh, and some poetry is okay for the missus, as long as it’s devotional in nature.

But if we are going to have fiction at all, why limit it? Why set boundaries based on the contours of this world? The Puritans had a reason that was at least consistent within its own worldview: there is a better world to come, and any time spent frivolously spinning tales about this fallen world and not focused on heaven is time ill spent. But most critics today, if you ask them, have no such ironclad worldview; they will admit to having as little clue about what’s to come as I do.

Privilege this world because it’s the only one? We already know that’s not true. Any scientist will tell you, given the vastness of the universe, it is almost impossible to think there are not other beings, other civilizations. And it is even more unlikely that these other beings and their civilizations much resemble ours. Actually, given the sheer numbers, one or more may well be similar to our own — but the variance, the range of myriad kinds of life that is probably out there, that is what we can barely imagine. Yet we will try.

And all these stories we amass in the three pounds of juice and gray matter sloshing around in our skulls — the real stories and the made-up ones: to what end? Where do they all go? Are they for anything, ultimately? Do they serve any purpose, other than to keep us entertained or to provide training exercises for our adaptation in various environments and scenarios, the better to pass along our genes?

Perchance to Dream

I got to thinking about that question this morning, as I was shoveling snow off the drive. Last night I had a dream that seemed to run through different stages of my life, reviewing various skills and talents I have exercised: I was a writer, then an actor, then a teacher. Interestingly — as dreams often do — rather than just replaying scenes from my life as if I were reliving actual memories, it cast me in unfamiliar dream environments, constructing new amalgamations from all the building blocks that I have soaked in both firsthand and from film and television to conjure a stage on which I have never performed, people I have never known, the hallways of a school I have never seen.

I got to thinking about that question this morning, as I was shoveling snow off the drive. Last night I had a dream that seemed to run through different stages of my life, reviewing various skills and talents I have exercised: I was a writer, then an actor, then a teacher. Interestingly — as dreams often do — rather than just replaying scenes from my life as if I were reliving actual memories, it cast me in unfamiliar dream environments, constructing new amalgamations from all the building blocks that I have soaked in both firsthand and from film and television to conjure a stage on which I have never performed, people I have never known, the hallways of a school I have never seen.

My dream was expanding on my lived life, as dreams are wont to do. We are driven to soak up stories throughout the day and to add our own, and then we close our eyes and our brain kicks into overdrive to keep churning them out even when we are asleep. Why?

I have heard many different theories. Evolutionary biologists, neuroscientists, philosophers, folks of various religious persuasions — they have as many theories as you have time to listen.

Still, I can’t help but wonder, where do all these stories go?

Have You Seen the Ghost of John?

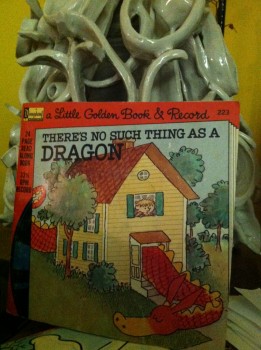

Here’s a corollary experience that factored into my musings while I was shoveling snow. The other day I picked up some old children’s records at a thrift store, some of which I recognized as having listened to when I was about the age my kids are. I thought it would be fun to put the old vinyl on the turntable and pull my seven-year-old and five-year-old away from their Wii and their Blu-rays long enough to experience this more primitive technology with me.

Here’s a corollary experience that factored into my musings while I was shoveling snow. The other day I picked up some old children’s records at a thrift store, some of which I recognized as having listened to when I was about the age my kids are. I thought it would be fun to put the old vinyl on the turntable and pull my seven-year-old and five-year-old away from their Wii and their Blu-rays long enough to experience this more primitive technology with me.

It was fun. They sat rapt as the needle crackled across the 40-year-old grooves, and we listened to There’s No Such Thing as a Dragon from Little Golden Books and The Three Billy-Goats Gruff: A Norwegian Folk Tale from Scholastic Records. On the flip side of the latter was Mother Ghost Nursery Rhymes: And Other Tricks and Treats.

Listening to that record, I experienced a sensation that is part of what drew me in to collecting vintage toys, I think. Not just the nostalgia, although of course that was present in abundance: the way hearing an old record or holding an old toy whisks one back across the decades, and there you are six years old again, curled up in the game room listening to the stereo or flipping through comic books or assembling your Fisher-Price camper and Adventure People together for a safari expedition.

No, not just nostalgia. As I have gotten into toy collecting, skimming through eBay listings hunting for beloved and cherished toys, more interesting than that feeling of intimate familiarity evoked by a well-remembered toy has been the numerous times when I’ve spotted a toy I did not remember at all — something I had completely forgotten existed, yet seeing it again brings back memories I didn’t know I had. Sure, I remember my Star Wars and G.I. Joe action figures well. But Magic Sand, which came in a genie-bottle-shaped rubber container? Or Food Fighters, the military action figures that were anthropomorphized pieces of food? They had been part of the landscape of my youth too, added back into the picture with their rediscovery like missing puzzle pieces.

I got that feeling listening to the nursery rhymes on this record — of recovering memories I didn’t know I had lost. I mean, I had zero recollection of any of them, until I heard them again. They were gone, not thought of in nearly 40 years. Yet sitting there listening with my kids, I not only remembered them, but I re-felt the emotions I’d had when I first heard them. A couple of those songs, sung in spooky voices backed by music in a minor key, kind of frightened me when I was a kid…

“Have you seen the ghost of John / All white bones and the rest all gone / Ooh, Oh Oh Oh Oh Oh / Wouldn’t it be chilly with no skin on?”

Thinking back now, straining to recall when I was five or six years old, I do believe I would try to be brave and press on but sometimes could not bear it and lifted the needle or went to find my mom.

Thinking back now, straining to recall when I was five or six years old, I do believe I would try to be brave and press on but sometimes could not bear it and lifted the needle or went to find my mom.

I’ve often been shaken by the thought that as we grow old we forget. This inevitable process of aging can be exacerbated by Alzheimer’s or dementia, or at any time by a traumatic brain injury. Memories wiped clean, stolen away. Yet that’s a continual process that’s happening now, every day of our lives. Most things we don’t remember from day to day. Cognitive scientists note that, far from being a weakness or flaw in the human brain, it is a necessary survival feature. If we remembered every little detail of everything we take in, we’d be overwhelmed. Our mind constantly prioritizes. A lot of stuff gets dumped into the storage files and tucked away, where it won’t clutter up all the stuff we do need to remember to function and thrive.

Yet — as this incident with the record demonstrates — it’s all still there. For forty years, that record and the feelings I felt listening to it were stored in some neurons in my brain. Had I never played this record for my kids, there’s no good reason to think I would have ever accessed those particular memories again. I would have gone along the rest of my days never knowing they were there.

Where Do All the Stories Go?

And along with those memories are all the stories I’ve ever read or heard or watched, and all the ones I’ve played out or written down or told, every one I’ve ever dreamed up. All that data — enough to keep every television and movie studio and book publisher busy for a while — recorded in microscopic electric pulses inside my head. We know how it’s possible for all that to be stored in such a small space because we all have computers. But here’s a puzzling question: Where will it all go?

Most of us have heard that energy is neither created nor destroyed, i.e., when our bodies turn to dust, all that electricity animating us does not cease to exist; it leaves the body. Does it just dissipate? All that stored data — all those stories — the energy that preserves them now will continue to exist, but what about the data? We know there are radio waves and TV signals flashing through the air all around us, inaccessible unless the proper reception device tunes into them. So, are all these signals inside my head only playable by one unique device — my brain — and when that device fails, the signals will be lost, unreadable forever? Or is this data being fed back into a system that is much larger than us, of which our brains are only individual units? Is there some kind of collective unconscious that is just as hungry for stories as we are, and that compels us as a species to keep generating simulations — both the ones that we really live and the ones that we make up, even when we are dreaming?

Most of us have heard that energy is neither created nor destroyed, i.e., when our bodies turn to dust, all that electricity animating us does not cease to exist; it leaves the body. Does it just dissipate? All that stored data — all those stories — the energy that preserves them now will continue to exist, but what about the data? We know there are radio waves and TV signals flashing through the air all around us, inaccessible unless the proper reception device tunes into them. So, are all these signals inside my head only playable by one unique device — my brain — and when that device fails, the signals will be lost, unreadable forever? Or is this data being fed back into a system that is much larger than us, of which our brains are only individual units? Is there some kind of collective unconscious that is just as hungry for stories as we are, and that compels us as a species to keep generating simulations — both the ones that we really live and the ones that we make up, even when we are dreaming?

That’s the sort of thing that sci-ficionados wonder. And it feeds back into our stories. And the simulations continue, and evolve, along with the human race. One mind consumes stories all day, creates some, and then sleeps and dreams more. So many stories in one brain, multiplied by the billions of people alive and the billions more who have receded further back in this great unfolding Story…

A New Paradigm

Come to think of it, the very notion of creating stories has taken on a new shape just in our lifetimes. For countless millennia, the Storyteller was a lone individual — a skald or bard holding an audience transfixed. The invention of written language expanded the potential audience, and many tellers could shape and mold and add their own flourishes to stories passed down — Homer refined tales that had been sung by entertainers down through generations, putting them into a codified form that we now recognize as the paragons of the tales of the Odyssey and the Iliad. Some scholars even dispute the idea that there was a single author named Homer, imagining the name instead as collectively representing a whole line of bards who shaped these tales over time.

Come to think of it, the very notion of creating stories has taken on a new shape just in our lifetimes. For countless millennia, the Storyteller was a lone individual — a skald or bard holding an audience transfixed. The invention of written language expanded the potential audience, and many tellers could shape and mold and add their own flourishes to stories passed down — Homer refined tales that had been sung by entertainers down through generations, putting them into a codified form that we now recognize as the paragons of the tales of the Odyssey and the Iliad. Some scholars even dispute the idea that there was a single author named Homer, imagining the name instead as collectively representing a whole line of bards who shaped these tales over time.

A modern equivalent might be the comic-book superheroes like Superman and Batman and Wonder Woman — they have known creators, but their stories over three quarters of a century have been revised and re-imagined by whole stables of authors who have left their own little marks, updating the characters for new generations to embrace.

With ongoing comics and television serials, writers meet together in writers’ rooms to flesh out the stories in a group. And fans — the audience — have unprecedented input into this process, their reactions of disappointment or approval giving real-time feedback via social media in ways that invariably influence the writers’ decisions for future story arcs.

Still, storytelling remained largely a lone project, not one generated by committee — until a momentous development in the 1970s, when a group of gamers led by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, in the Minnesota Twin Cities and Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, created a new type of game. It became known as role-playing. Role-playing games fostered the creation of narrative by a community — 6 or 8 people sitting around a table — working together to “play” out the story with a few rules, some character sheets, and a handful of odd, colorful polyhedral dice.

When the Internet explosion hit a mere two decades later, role-playing games became the blueprint for online gaming — for MMORPGS and shared worlds like World of Warcraft and Second Life. Suddenly people by the thousands were interactively creating stories that unfolded in secondary, virtual realms.

“Reality”: I do not Think it Means What You Think it Means

Now stories are being generated not just in the heads of a few ordained “storytellers” of society, but by larger communities whose populations sometimes rival that of real cities. Sci-ficionados are there every step of the way, sometimes anticipating these paradigm shifts in their imaginative stories decades in advance, always at the forefront of them when they suddenly burst on the horizon.

This Reality you speak of… We are not only shaping the stories and the stories shaping us, but in the process, perhaps, we are shaping Reality? I’ll bet there’s a story in that.

Nick,

Fascinating stuff. And I agree completely that the communal storytelling of role playing is both the most fascinating evolution of mankind’s obsession with stories, while somehow feeling very old, primal almost. The way perhaps people used to tell long stories, sitting around a fire and making up lies together to entertain fellow travelers.

I think it pays to explore and understand man’s obsession with stories and fiction. Our ability to care deeply for characters we know don’t even exist. As we get closer to understanding that, we get closer to comprehending what it truly means to be human.

Great article!

I’m always wondering about what it is that makes one person an avid reader while others never read for the sheer fun of it. Or why my brothers seemed to outgrow comic books but I still love them.

I’ll be the first to admit, I need sci-fi/fantasy books to escape from reality for just a little while, almost daily.

Excellent article indeed,

In a similar vein, think of the Sci-Fi/Fanatsy “producers” who are exhorting us to not only “think outside the box,” but actually to consider pressing/rebelling against the status quo… consider for a moment the “subtly” hidden calls for change, if not outright rebellion in “The Matrix,” and more current works like the “Hunger Games”…and I guess the Star Wars “rebellion” to some extent.

Though I still thoroughly enjoy the “escapist” aspects of Sci-Fi and Fantasy, I am even more impressed when meaningful messages are woven throughout.

Thanks Nick 🙂

Good point AWAbooks. but the meaningful messages has to be subtle and constant throughout the story, almost fooling the reader to subliminally open their mind, Otherwise it can be preachy which is a huge buzz kill when you’re reading for leisure.

John ONeill,

“As we get closer to understanding that, we get closer to comprehending what it truly means to be human.”

Yes indeed. My interest in this topic has influenced some of my recent reading:

The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human (2012) by Jonathan Gottschall gives a pretty scientifically grounded, evolutionary overview.

At the other end of the spectrum is Grant Morrison, who, in his 2011 book Supergods, espouses the notion of a sort of oversoul/super-mind of which we are components generating stories to guide our own evolution (he claims to have caught a glimpse of this over-arching super-reality in drug-fueled visions!).

Morrison is a popular comic-book writer, and the book is nominally an overview of the progression of comic books through their roughly 85-year history. However, he uses the platform as a jumping-off point to share his own mystical and pretty far-out views.

The way he sees the intersections between fiction and reality I find somewhat resonant with my own thinking. Sure, fictional characters we feel so deeply about don’t exist, but yes they do. They don’t have the material properties we do, but they exist inside our minds, and our minds are of physical substance, so we imbue them with some of our existence. (Tolkien saw this as a direct analogue to how we are bestowed existence from the “mind” of God — he called our own imitative acts of creation “sub-creation”).

Endlessly fascinating.

kid-greg,

Me too!

AWAbooks,

Good point about The Matrix and The Hunger Games challenging us to question the status quo and reality — a tradition that runs throughout the literature, with antecedents in Orwell and Huxley, Vonnegut and Dick, and too many more to mention.