Alone at the Edge of the World: The Witch

Have you ever considered the possibilities that would open up if certain common modern inventions had appeared much earlier than they actually did? (If you haven’t, humor me for the next few minutes and pretend that you have.)

Imagine, for example, that some starch-collared, black-hatted pre or proto-Edison had invented motion pictures some three hundred years before that technology really did arrive. What sort of films would have resulted? What kind of movies would have been made, for instance, by the dour puritans of New England?

Somehow, I don’t think that particular group would have been big on romantic comedies or caper pictures, and their 50 Shades of Grey would have been a sober documentary on the winter landscape of Massachusetts instead of… well, you know. Scary movies, on the other hand — they might well have gone in for those, and if you had gotten the corn shucking and butter churning done early some Saturday night in 1660, and had hopped on the family mule to trot into town to the Salem Cinema 6 to see a horror movie, you might have seen something very like The Witch.

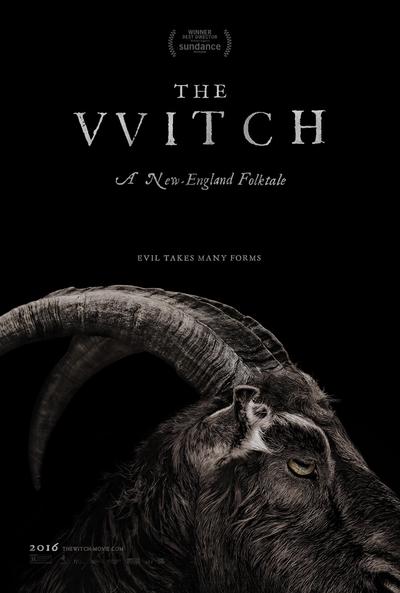

Written and directed by Robert Eggers, The Witch is subtitled “a New England folktale,” and it has all the stark simplicity and resonance that you would expect from something derived from such mythic origins.

In outline, the tale couldn’t be simpler. In an unnamed town in an unnamed American colony sometime in the late seventeenth century, a father, William (Ralph Ineson) severs all connection with his village neighbors and takes his family to an isolated spot at the edge of the wilderness, there to try and establish an independent farm far away from the compromise and corruption that he sees in the colony’s established church.

The family consists of William’s wife Katherine (Kate Dickie), their nineteen year old daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy), their twelve year old son Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), six year old twins Mercy and Jonas (Ellie Granger and Lucas Dawson), and Samuel, a newborn. (We never learn the family’s last name.) One day, shortly after arriving at their cheerless new home, Thomasin is charged with watching the baby while the others labor around the farm. In the space of a few seconds, while she covers her face to play peek-a-boo, Samuel simply vanishes.

Katherine is frantic but a search turns up nothing. William decides that his son must have been taken by a wolf. We know what the others do not — Samuel has been kidnapped by a witch who lives in the woods. She has murdered the child and bathed in his blood.

Things quickly go from bad to worse — the farm proves barren and unfruitful, and when William and Caleb go hunting in the woods in an attempt to supplement their meager fare, their luck is no better. Under mounting inner and outer pressures, the family starts to disintegrate. A disconsolate Katherine wants nothing more than to return to England, while the twins begin to spitefully accuse Thomasin of doing away with the baby. (She responds by telling them that they had better watch out, because she is the witch of the wood, a strategy that is destined to backfire badly.)

Caleb, wracked with guilt over his growing sexual desires and terrified of the damnation that he believes he can’t escape (William’s inflexible belief in predestination prevents him from offering any reassurance to his son), ventures deep into the forest himself, there to have his own encounter with a seductive and elemental evil. It’s a riveting moment of dreamlike, fairytale horror. Unlike his brother Samuel, Caleb returns to his family, but he’s not the same boy who left home…

I’ll say no more about the story itself except to say that once the film begins you can easily see where it’s going — and that’s a virtue, not a defect. You know immediately that things are not going to go well for this family, which within the context of the world that they inhabit is just as it should be. The Witch can’t be charged with predictability because it’s not trying to make you jump with the unexpected; it’s building the kind of dread that comes from knowing that the worst will happen. There’s a deep satisfaction in seeing this archetypal material handled with such intelligence and care, and it’s an intelligence and care that pervade every aspect of the film, from the beautiful period detail to the gorgeous, though dark, compositions. (The production design is by Craig Lathrop and the cinematography is by Jarin Blaschke.)

It’s not just intelligence that’s at work in this film, but empathy is present too, and this is especially apparent in the treatment of the characters. These rigid, Calvinistic puritans are so far removed from us in their values and their worldview as to seem almost to belong to a different species, but the film never condescends to them, never implies a cheap moral superiority in those who made the movie or in those who watch it; there is never a moment in which we hear the filmmakers say, sotto voce, “how ignorant these people are, how barbaric, how intolerant, how wicked.” Instead, William and his unfortunate family are accepted on their own terms and the dignity of their physical and moral struggle is fully acknowledged, even as we see them display the folly and frailty that is characteristic of all people, everywhere. It’s an extraordinary act of sympathetic imagination.

This generosity is clearest in the treatment of William, who could easily have been a one-dimensional villain, a petty tyrant and a canting fanatic. Instead, in the hands of Eggers and Ralph Ineson, he’s a decent but fallible man who deeply loves his family and desperately wants to protect them, all the while unwittingly leading them to disaster. He’s no hypocrite (though Thomasin accuses him of being one), except in the sense of being someone who fails to live up to his own ideals, not out of opportunism or cynicism, but out of plain human weakness. No one condemns him more heavily than he does himself.

An equal understanding is extended to all the characters, and the performances of all the players are very fine indeed, with pride of place going to Ineson and Anya Taylor-Joy’s Thomasin, a loving, lively young woman who, through no fault of her own, finds herself having to make an ultimate, an eternal choice… at the behest of the One Who Always Lies.

The Witch is being marketed as a horror movie, and that’s leading to some confusion and discontent among audiences who are expecting the usual dose of soundtrack-signaled shock shots. But this is a horror movie, though of a different, subtler kind than many Freddie Kruger-fed viewers are used to. The fear in this film (and it pervades everything — I guarantee you’ve never seen a more sinister goat or rabbit) comes not from physical threats, but from metaphysical ones. In the shadow of the endless, silent, trackless forest (from the beginning of our history, the great American symbol of chaos and primal fear), these people are utterly alone. They’re not alone in an old dark house or at the deserted summer camp or in the derelict amusement park. The truth is far, far worse than that; they’re alone in the universe.

Whoever, whatever their God was in England, His love and power did not follow William and his family across the Atlantic; on this bleak and sunless shore, under the brooding gaze of the ancient trees, at the very edge of the world, their God is indifferent, or powerless. They find themselves abandoned in a world feverish with evil.

To keep back the physical darkness they have only feeble, guttering candles, and to keep back the spiritual darkness they have only their own failing strength and defective understanding. It’s not enough. Their harsh doctrine of hidden election isolates them from each other as it does from their God and leaves them defenseless against the very real evil that seeks to destroy them. Under the attacks of that dark force, they cannot support each other, cannot comfort each other, and ultimately cannot even believe each other.

The Witch resonates with echoes of The Blair Witch Project, Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s tale of a Satanic Sabbath, “Young Goodman Brown.” But it is very much its own thing, intelligent, sympathetic, austere, beautiful, tragic… and damned frightening. Set aside the negative things you may have heard about it — it deserves to be seen. See it.

Thomas Parker’s last article for us was Classically Awful or Awfully Classic: A.E. Van Vogt’s The World of Null-A.

“An extraordinary act of sympathetic imagination.” That is absolutely perfect phrasing, dad, and is why the movie has done as poorly with audiences as it has… Many people today are not equipped for sympathetic imagination. Our American world does not encourage it.

Brilliant movie with well rounded characters and subtle and not so subtle theological themes that were critical to the plot. Samuel, the American world is not equipped for anything other than worship of self. You don’t have to go to a movie to see the handiwork of the Prince of Lies.

When I originally saw the trailers for this movie, I knew it was something I wanted to see—it looked like my kind of horror movie. After reading this review, it spurred me on to go see it today. I thought it was an excellent horror movie.

In addition to “Young Goodman Brown”, this movie also reminded me of M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village. Similarities in tone and, I think, cinematography.

After seeing the movie I think this review was spot-on. But I did crack up at this line: “These rigid, Calvinistic puritans are so far removed from us in their values and their worldview as to seem almost to belong to a different species . . .” Believe it or not, some of us Calvinists still exist! And, for what it’s worth, I think the historical Puritans were far less dour in reality than they are usually painted. It’s unfortunate that the Salem witch trials tend to overshadow their cultural and historical pros.

James, I was using “us” in the part you quoted to mean the postmodern, secular materialist in general. I myself am rather closer to the people in the movie than is wise to mention in polite company these days.

Cool to know. I wasn’t criticizing. And I definitely get your point since I just finished my phd at a secular program! It’s just that I always get a giggle when I hear comments like that, as well as adjectives like “puritanical.”