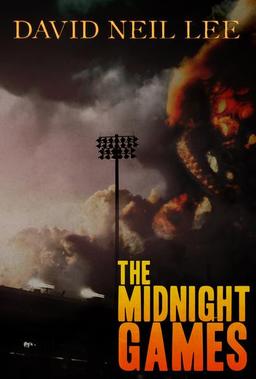

The Midnight Games and Why I Wrote Them

“One might not think of our city as a muse,” began a recent review of my first YA horror novel The Midnight Games in a Hamilton magazine. But if you ask me, good horror novels, because they assume that monstrous secrets lurk behind the facades of everyday life, always convey a strong sense of place: I’m thinking of the New York City of Whitley Streiber’s The Wolfen, the Los Angeles of Robert McCammon’s They Thirst, or even the east coast gothic of Tim Wynne-Jones’ Odd’s End (which is an archetypical Canadian production — a horror novel about real estate).

“One might not think of our city as a muse,” began a recent review of my first YA horror novel The Midnight Games in a Hamilton magazine. But if you ask me, good horror novels, because they assume that monstrous secrets lurk behind the facades of everyday life, always convey a strong sense of place: I’m thinking of the New York City of Whitley Streiber’s The Wolfen, the Los Angeles of Robert McCammon’s They Thirst, or even the east coast gothic of Tim Wynne-Jones’ Odd’s End (which is an archetypical Canadian production — a horror novel about real estate).

In any case, Hamilton, Ontario, just southwest of Toronto, is a grimy little city that, like a lot of its relatives in the USA, dearly misses the great days of its industries (in this case, steel); days that have passed and that will not return again. One result of this is a working class culture, deeply depressed, that tends towards the nostalgic, and by nature I am a relentless optimist who regards nostalgia with a distaste approaching revulsion. For all that, I’ve lived in Hamilton since 2002 and the city has been good to me in many ways; let’s just say it’s enabled me to write a lot of books.

One day a local Hamilton publisher, Noelle Allen, put out a Facebook call for Hamilton-based books on behalf of her company, Wolsak & Wynn. I replied, “What we need is a horror novel, set in Hamilton, that people will read on the bus.” I volunteered to write such a novel.

Like it or not, for the past twelve years my family and I have lived a couple of blocks from Ivor Wynne, the local football stadium, and we hear all the noise from the Tiger Cats games. So I began a novel in which my protagonist hears a racket from the stadium at night, which he thinks of as “midnight games.” However, they are not games at all, but the cruel ceremonies of a local cult which is trying to summon to earth the Great Old Ones of the H.P. Lovecraft Cthulhu Mythos; trying with what turns out to be a fair degree of success.

Before The Midnight Games I’d written several non-fiction books and one literary novel. I labored over the literary novel for years, whereas as soon as I agreed to write The Midnight Games, I received an offer of acceptance for a Ph.D. program in English at the University of Guelph. Faced with four years of hard scholarly work and volumes of academic writing to be done, clearly The Midnight Games was a book that needed to be written quickly.

Contingency inspires improvisation; once I put in a few elements that I felt had to be in the book — my young protagonist Nate; the ceremonies in the stadium; a feisty young librarian who guards the public library’s copy of the Necronomicon — plot elements seemed to come to me out of nowhere, some of them inspired by key elements from my favorite works of horror. How does the Cthulhu cult (the Hamilton branch is called The Resurrection Church of the Ancient Gods) deal with its enemies? They hand them a parchment printed with ancient runes, quite similar to those from M.R. James’ “Casting of the Runes” — a story which I long ago read and forgot, but I often watch its stupendous film adaptation, Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon.

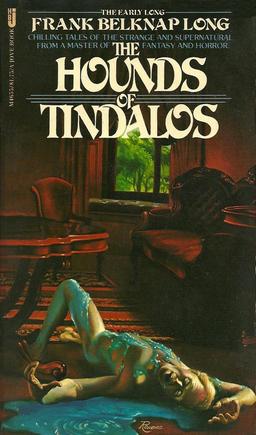

What do these runes summon? — well, in the story and film, demons from hell — but such things don’t exist in the Lovecraftian cosmology, so how about the Hounds of Tindalos, those creations of a blasphemous geometry that Frank Belknap Long created, influenced as he was by Lovecraft’s unique blend of horror and science fiction?

What do these runes summon? — well, in the story and film, demons from hell — but such things don’t exist in the Lovecraftian cosmology, so how about the Hounds of Tindalos, those creations of a blasphemous geometry that Frank Belknap Long created, influenced as he was by Lovecraft’s unique blend of horror and science fiction?

What sort of monsters does the cult summon? — well how about those hideous prickly house centipedes that I scoop out of the bathtub of our old house from spring till fall every year. I don’t kill them, I put them in a jar and throw them in a garden — what if they were some sort of hmm, spawn of Yog-Sothoth, summoned here by the games? What about if one of them thrived in our garden, and grew and grew and grew?

I know what you’re thinking. “Dammit that sounds like fun. Why don’t I do that?” Well, if you’re a Black Gate reader, chances are that you do do that. So you know, it is fun. But it is also a way, as a writer, of configuring and re-configuring yourself in relation to your world. What is Nate doing here? What am I doing here? Why is some lonely teenager’s quest — he’s just trying to do the right thing at the right time, and meanwhile keep his ass in one piece — seem meaningful and in some way, true? What is there, embedded in this world of danger and horror and derring-do, that feels so strangely pertinent and personal and real?

It is more interesting to pursue these questions in fiction than to try to answer them in an essay. The surprising thing to me is how, in the intense months that I set aside to write the book, it all has become very real. When I look at the new Tim Horton Field that stands where Ivor Wynne used to be, all I can think of is the final apocalyptic Midnight Game that (in the book) destroys the old stadium. When I cross the overgrown railroad tracks that crisscross the East End, I think of what happens there at night (in the book), when phantom black freight cars carry unearthly cargoes to mysterious destinations.

The publisher wants a sequel, and regardless of sales or income, I am determined to write her one as soon as I’m done my dissertation. Already I’m thinking of taking poor Nate farther and farther into a universe of Lovecraftian horror, with the Resurrection Church, thwarted in Hamilton, searching the BC coast for the long-sunken Nazi spaceship Oberth A-7 (what? — never heard of it, you say?), farther into that scariest of regions, stuck between the far future and the distant past: the dark and puzzling present.

David Neil Lee is the author of the novel Commander Zero and several non-fiction books, including The Battle of the Five Spot: Ornette Coleman and the New York Jazz Field; Stopping Time: Paul Bley and the Transformation of Jazz; and the award-winning best-seller Chainsaws: a History. He lives in Hamilton, Ontario, where he is writing his Ph.D. dissertation on the history of improvised music in Toronto.