Review: Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear — Actually Rather Wise

I wanted — expected — to hate this book.

I only know the work of Elizabeth Gilbert from the movie Eat, Love, Pray: Men Are Kind of Expendable (And Arranged Marriages Are Cute as Long as You Are a Bystander) which I believe may not quite have caught the depth of the original book.

So Big Magic… Creative Living…

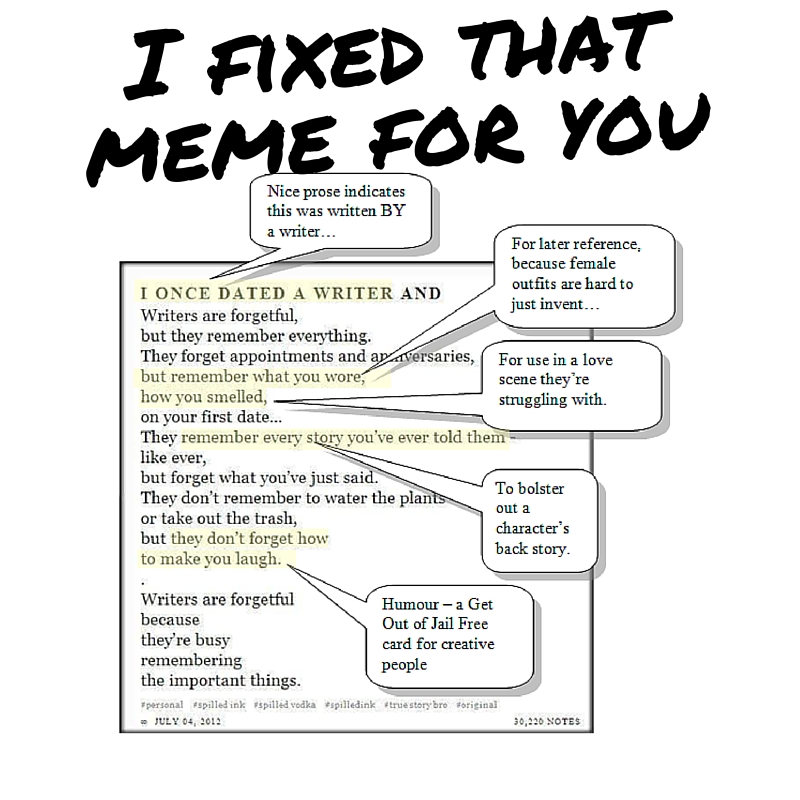

OMG this is where those damned writer memes come from! (See my ranty guest post on Charles Stross’s blog.)

But actually, behind the willful whimsy Elizabeth Gilbert speaks wisdom that applies to we Black Gate folk, and SF&F fans in general. It also reminds me of a long lost essay by Ryan Harvey entitled something like, “What if the Fifteen-Year-Olds were right?”

It has six parts, with inspiring titles. However, the structure is more literary than… well structural, and really she’s taking us on a tour of her mental map of the creative life, so I’ll just tell you why I was impressed (or in one case, unimpressed).

She kicks off (“Part 1: Courage” — see what I mean?) by serving up one of those folksy tales about how the fame-indifferent and incredibly unprolific poet Jack Gilbert (no relation) told his students that they needed courage in order to “bring forth the work”.

Oh no! The memes! The memes!

But then she goes onto another story, about a middle-aged friend who went back to figure skating as a hobby because, ultimately that was how she got her creative kicks. There was no point to skating – she wasn’t going to make a career out of it – she just wanted to do it, so she did despite all the voices presumably telling her she was too old and wasting her time and being undignified…

Gilbert then — as always, with anecdotes, and this book is worth reading for those alone — more gently than I would do, points out that fear of being creative is boring and doesn’t make you special and that you need to have an accommodation with your fear…

…and I’m reluctantly hooked.

And then the book rambles on entertainingly and mostly wisely around her central themes:

First, she’s really passionate about the idea that creativity should be fun for its own sake. We shouldn’t burden our work with expectations of it being important, or a source of income (hah!), or worry that anybody is going to pay us much attention anyway, or — yes — hold onto the fears that stop us creating. Of Harper Lee she says:

I wish that, right after Mockingbird and her Pulitzer Prize, she had churned out five cheap and easy books in a row— a light romance, a police procedural, a children’s story, a cookbook, some kind of pulpy action-adventure story, anything.

She’s not just talking about writers. Remember that middle-aged ice-skater?

You want to write a book? Make a song? Direct a movie? Decorate pottery? Learn a dance? Explore a new land? You want to draw a penis on your wall? Do it. Who cares? It’s your birthright as a human being, so do it with a cheerful heart.

The same, by extension, applies to cosplay, fan fiction, fan art, role playing and all the fun mostly non-remunerative things we love doing. It’s not earth shattering, but it’s lovely to see it set out so eloquently in what is basically a manifesto for whenever anybody makes you feel childish about your hobbies.

She says, you can only “follow your own fascinations… the rest will take care of itself.”

She also urges us to give ourselves permission to be creative. We shouldn’t wait until we’ve done all the possible research, or taken a college course in our chosen medium — she is scathing about the wisdom of running up debt in this way, not least because it burdens your creativity with financial expectations. Similarly, worrying about originality is a trap — even Shakespeare wasn’t actually original having lifted his stories from elsewhere.

Finally — and it’s hard to sum up what she articulates at such length with so many stories — we should practice a kind of knightly humility around our creativity. We should at once treat it as the most important thing in the world and the most trivial, hopping between stances depending on which is the most productive place to stand.

Here she descends into whimsy. For Gilbert, Ideas are independent entities — angels or sprites even. They come to you wanting to be born. Sometimes they approach the wrong person and you must send them away. Sometimes they get bored waiting… bleh!

Even her own stories belie this! She gets her ideas by feeding her mind with interesting things — history, horticulture, real-life adventure (all that eating and praying) — waiting until an interesting idea pops up, then researching around it to flesh it out.

Except… except… there’s something healthy about this approach. By externalising creativity, she detaches it from her ego, removes the pressure, the responsibility to live up to expectations, and makes it easier to just abandon projects that won’t go anywhere.

Sometimes it works.

Sometimes it doesn’t.

Sometimes you have to let it go.

And that humility also takes us back to creativity should be fun. Ultimately your creative pursuits don’t matter, so why tear yourself up about them?

And yet people do.

She describes young writers stalled because somebody told them that only work that hurt counted, and aspiring musicians destroyed by drugs while emulating Charlie Parker. And, of Tom Waits, who she interviewed, she says:

He wanted to be complex and intense. There was anguish, there was torment, there was drinking, there were dark nights of the soul. He was lost in the cult of artistic suffering, but he called that suffering by another name: dedication. But through watching his children create so freely, Waits had an epiphany: It wasn’t actually that big a deal. He told me, “I realized that, as a songwriter, the only thing I really do is make jewelry for the inside of other people’s minds.”

And that’s what she’s telling us: Be serious about having fun being creative but don’t burden it or yourself by taking it too seriously or expecting too much from it.

A happy, affirming read from a successful author.

M Harold Page is the sword-wielding author of works of lyrical and poetic magical realism with a strong pacifist theme such as Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”). For his take on writing, read Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)

“Be serious about having fun being creative but don’t burden it or yourself by taking it too seriously or expecting too much from it.”

This!

I design board games. Not for a living – but I have published several and I do get some royalties from them.

I started as most other designers: For fun. And I still doing it for fun. Every time I hear someone saying “Oh, someone should do THAT! THAT will surely become a megabestseller! I cringe. Because every time I tried to do something that Im not totally convinced of, just because the market would (probably) look favorable on it I crashed and burned and produced drek that was unispiring and boring. Now I only pursue ideas that really interest ME and I I dont care if there would be a market for it. Of course I still have failures, but somewhat ironicly Im much more succesfull of getting my games published than before. So I can really, really really underline would Gilbert wrote!

(And now that I try to write fiction I try to implement the same idea and try not to think to much about what would sell. Thats the perk of having a day job…

There are ways of handling doing it as a pro. I wrote up my take here: http://www.mharoldpage.com/big-magic-creativity-beyond-fear-when-youre-a-professional-with-responsibilities/

Thanks for the link! Interesting read!

[…] Rezensent drüben in Black Gate hat das Buch Big Magic von Elizabeth Gilbert (Eat Pray Love, The signature of all things […]

Peer on his German blog (http://www.spielbar.com/wordpress/2016/02/27/15834) makes the point that in table top games development, one must be professional in one’s dealings with producers and companies – that at that point one must take one’s product seriously.

I think this is also true of fiction and most other creative pursuits. I sore repent me that I did not take Gilbert to task for this in the article.