Rediscovery of the North: Nelvana of the Northern Lights

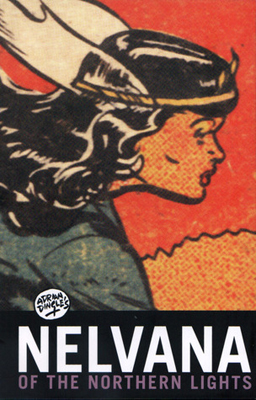

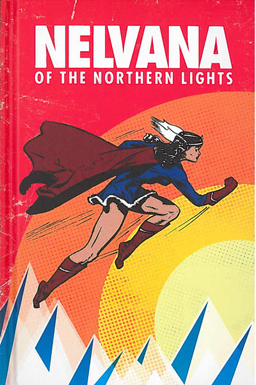

In 2014, following a successful Kickstarter campaign, Hope Nicholson and Rachel Richey published Nelvana of the Northern Lights, a trade paperback reprinting all the appearances of the eponymous Canadian super-heroine from the 1940s. IDW gave the book a wider release in hardcover and paperback later that year. It contains over 300 pages of comics written and drawn by Nelvana’s creator Adrian Dingle, mostly in black and white, along with forewords by the editors, an introduction by Dr. Benjamin Woo (Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Carleton University), and an afterword by Michael Hirsh (an artist and animator who founded a well-known animation studio named for Nelvana). It’s a nice package, designed by Ramón Pérez, a past winner of the Eisner, Harvey, and Shuster Awards.

In 2014, following a successful Kickstarter campaign, Hope Nicholson and Rachel Richey published Nelvana of the Northern Lights, a trade paperback reprinting all the appearances of the eponymous Canadian super-heroine from the 1940s. IDW gave the book a wider release in hardcover and paperback later that year. It contains over 300 pages of comics written and drawn by Nelvana’s creator Adrian Dingle, mostly in black and white, along with forewords by the editors, an introduction by Dr. Benjamin Woo (Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Carleton University), and an afterword by Michael Hirsh (an artist and animator who founded a well-known animation studio named for Nelvana). It’s a nice package, designed by Ramón Pérez, a past winner of the Eisner, Harvey, and Shuster Awards.

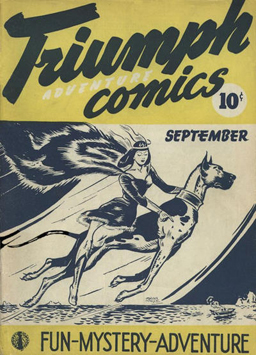

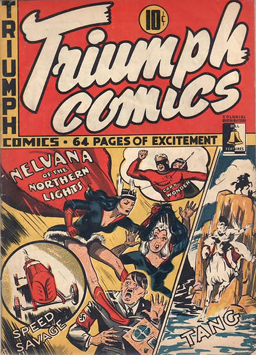

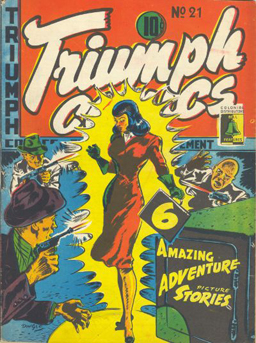

The book also has a one-page biography of Dingle, who sounds like an interesting character. Born in Cornwall in 1911, his family moved to Canada in 1914, and by the 1940s he was a professional illustrator in Toronto. In 1941 he became one of the founders of a new comics publisher, Hillborough Studios. A law passed late in 1940 had restricted the importation of “non-essential” goods from the United States, including comic books. As a direct result, a Canadian comics industry was blossoming, publishing so-called “Canadian Whites,” black-and-white books with colour covers. So Dingle’s Nelvana appeared in Hillborough’s Triumph-Adventure Comics starting with the first issue, in August of 1941; Dingle took the book and character to Bell features starting with the seventh issue, where they stayed until the book’s thirty-first and last issue in 1946. A final appearance by Nelvana in a 1947 colour comic tied up most of the dangling sub-plots.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the story is that Dingle credited a friend of his with the inspiration for Nelvana. Franz Johnston was part of the Group of Seven, an association of Canadian artists who created the country’s first significant movement of painters; they travelled around the country to find inspiration in the Canadian landscape and developed new techniques for painting it. Johnston shared stories with Dingle of a trip he took to the north, where he met an Inuit elder named Nelvana. From Johnston’s stories Dingle created his Nelvana, a mythic Axis-smashing superheroine.

Dingle plotted his storylines fairly well, though he switched tones and subgenres freely between — and sometimes within — serials. The first story opens with an Inuit chief, Tadjo, whose people are starving due to the disappearance of fish and seal from the Inuit territories (Dingle uses the word “Eskimo,” now widely viewed as pejorative). Tadjo appeals to the half-divine Nelvana, daughter of the great god Koliak, who answers his prayer and then herself calls her brother Tanero to her side. They discover that agents of a European dictatorship have caused the famine through weird science as a side effect of a scheme for conquest, and promptly thwart the evil plot.

Dingle plotted his storylines fairly well, though he switched tones and subgenres freely between — and sometimes within — serials. The first story opens with an Inuit chief, Tadjo, whose people are starving due to the disappearance of fish and seal from the Inuit territories (Dingle uses the word “Eskimo,” now widely viewed as pejorative). Tadjo appeals to the half-divine Nelvana, daughter of the great god Koliak, who answers his prayer and then herself calls her brother Tanero to her side. They discover that agents of a European dictatorship have caused the famine through weird science as a side effect of a scheme for conquest, and promptly thwart the evil plot.

With the move to his new publisher Dingle launched a new storyline; Tanero is quietly dropped, and Nelvana adventures into the subterranean lost world of Glacia, which has been caught in suspended animation for millions of years. She faces a variety of dangers and court intrigues, and when all finally seems quiet a Japanese bomb crashes into the hidden realm. This signals a shift in venue, and Nelvana drops out of her own story, as Dingle follows the adventures of engineer “Spud” Jodwin trying to prevent Japanese sabotage of the then-under-construction Alcan Highway. Nelvana returns after a few chapters, and the story shifts again, as she relocates to southern Ontario, adopts the identity of secret agent Alana North, and gets involved in a case involving German spies and a freeze ray. The last serial, which concludes (after some stand-alone tales) with a colour chapter, involves Nelvana trying to save the world from an invasion by Etherians, a people from the “ether wave strata” who are threatened by human radio broadcasts.

The stories are plot-oriented adventure tales, with, as you might expect, minimal characterisation. Given that, they’re well-crafted. The biggest issue, again as you might expect from a World War Two–era comic, is the racist depiction of the Japanese. The depiction of the Inuit seems to me to be more nuanced, the characters drawn and written as individuals — though later appearances of Inuit characters and communities in the book portray them as dupes of sinister foreign agents. Conversely, Nelvana herself is a fully-realised active character with a variety of powers. She’s drawn as beautiful, even glamorous, but at least to my eye she’s not excessively sexualised. She is occasionally captured, and sometimes rescued by others, but not with any regularity; she’s definitely the lead in these stories.

The stories are plot-oriented adventure tales, with, as you might expect, minimal characterisation. Given that, they’re well-crafted. The biggest issue, again as you might expect from a World War Two–era comic, is the racist depiction of the Japanese. The depiction of the Inuit seems to me to be more nuanced, the characters drawn and written as individuals — though later appearances of Inuit characters and communities in the book portray them as dupes of sinister foreign agents. Conversely, Nelvana herself is a fully-realised active character with a variety of powers. She’s drawn as beautiful, even glamorous, but at least to my eye she’s not excessively sexualised. She is occasionally captured, and sometimes rescued by others, but not with any regularity; she’s definitely the lead in these stories.

Dingle’s art is the most powerful aspect of the book. He uses shadows liberally, building an atmosphere with swirling, expressive strokes of ink. It’s both moody and energetic. His figure drawing in particular becomes smoother as the book goes on, but even when his art is at its loosest, it’s still fun to look at. You can see that his cartooniness is based on a real sense of how things look — how fabrics hang and crease, how snow in a forest looks just after it’s fallen and when it’s been disturbed. His inventiveness seems limited, in that the otherworlds Nelvana finds aren’t depicted with any particular originality, and he only seems to enjoy drawing backgrounds of northern wilderness settings. But then that means that his characters take centre stage, and even at his worst Dingle’s always able to convey emotion through facial expression, stance, and gesture.

His storytelling starts out fairly standard for a North American comic from the Golden Age, but in the second serial Dingle tries out some new devices — panel borders fall away, and page composition becomes a bit more complex. You can see him varying his panel shapes even in the early pages, and as he goes on he finds new ways to move the eye around the page. Oddly, he briefly reverts back to a much more traditional grid layout when the story focusses on “Spud” Jodwin, only to start experimenting again as Nelvana returns. Either way, Dingle’s page layouts work, although I found the emphasis occasionally seemed odd; the prominence of an image didn’t always relate to its significance to the story, and conversely key story moments seemed sometimes hurried or underplayed.

His storytelling starts out fairly standard for a North American comic from the Golden Age, but in the second serial Dingle tries out some new devices — panel borders fall away, and page composition becomes a bit more complex. You can see him varying his panel shapes even in the early pages, and as he goes on he finds new ways to move the eye around the page. Oddly, he briefly reverts back to a much more traditional grid layout when the story focusses on “Spud” Jodwin, only to start experimenting again as Nelvana returns. Either way, Dingle’s page layouts work, although I found the emphasis occasionally seemed odd; the prominence of an image didn’t always relate to its significance to the story, and conversely key story moments seemed sometimes hurried or underplayed.

But then, this is work from what is effectively the dawn of the medium. Dingle’s making up the rules as he goes. It’s remarkable how well the series holds together overall, notwithstanding frequent changes of direction and supporting cast members who drop out of the strip with no warning. There’s a pulpy feel that holds steady throughout, with deathtraps and freeze rays and lost worlds. Dingle’s Etherian aliens are less than threatening visually, but the unpredictability of the strip makes up for it. On a practical level, Nelvana’s vaguely-defined powers tend to undercut any suspense, but countering that is a desire to see where Dingle takes the story next. It’s not the usual adventure formula, but it works.

The idea of the North is a major motif in Canadian art and indeed the Canadian psyche: it’s roughly the equivalent of the western frontier in American mythmaking. It’s not surprising that one of the first Canadian super-heroes should be given an origin in the north. On the other hand, there’s no sense here of a garrison mentality. Nature isn’t foreign. In fact, it has to be protected from invaders. That’s Nelvana’s role. Dingle’s imaginative sympathies seem to be wholly on her side: his art is at its most impressive when it presents snowstorms, choppy oceans, winter forests, the aurora borealis in the night sky.

Nelvana and the Canadian Whites haven’t had much influence on Canadian culture — most Canadians don’t know about the character, notwithstanding her appearance on a postage stamp twenty years ago (and notwithstanding a tip of the hat to Nelvana from John Byrne in the pages of Alpha Flight, when he imagined a goddess named “Nelvanna” as the mother of his character Snowbird). In general I feel that English Canada has tended to lack much of a sense of its commercial fiction, particularly from past decades. We don’t often think of ourselves as having produced comics, pulps, or cheap paperbacks. Consciously or not we (most of us) feel that there’s a strata of pop literature missing. That writers like A.E. Van Vogt had to go south to find publishers. That may be changing now, as work like Nelvana is brought back into print. That’s to the good; but the first and most important thing is the work itself. And in this case, it’s strong, distinctive, original work. For anyone with an interest in Golden Age comics, this is an important book.

Nelvana and the Canadian Whites haven’t had much influence on Canadian culture — most Canadians don’t know about the character, notwithstanding her appearance on a postage stamp twenty years ago (and notwithstanding a tip of the hat to Nelvana from John Byrne in the pages of Alpha Flight, when he imagined a goddess named “Nelvanna” as the mother of his character Snowbird). In general I feel that English Canada has tended to lack much of a sense of its commercial fiction, particularly from past decades. We don’t often think of ourselves as having produced comics, pulps, or cheap paperbacks. Consciously or not we (most of us) feel that there’s a strata of pop literature missing. That writers like A.E. Van Vogt had to go south to find publishers. That may be changing now, as work like Nelvana is brought back into print. That’s to the good; but the first and most important thing is the work itself. And in this case, it’s strong, distinctive, original work. For anyone with an interest in Golden Age comics, this is an important book.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy a collection of his essays for Black Gate, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.