Guides to Worlds Fantastic and Strange

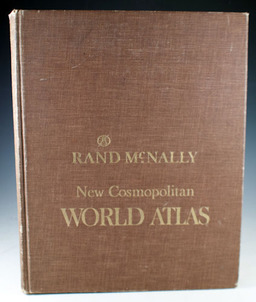

I’ve always loved maps — following rivers to the seas, tracing the shores of those seas, and then crossing them by fingertip to a distant land. My dad had a giant Rand-McNally atlas that I took possession of when I was ten or eleven and never returned. I would pore over its pages, puzzling out how to say the names of cities like Dnepropetrovsk or Tegucigalpa and wondering what exactly was the Neutral Zone between Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

Today, my favorite atlas is the Cram’s Unrivaled Family Atlas of the World 1889 that my grandfather scavenged from a work site. As with my dad’s, I quickly assumed ownership of the book. Better than a lot of history I’ve read, it conveys the reality of the past in finely drawn lines. The vast scope of the British and Russian empires — the web of conquered lands covering Africa and Asia — are right there in clear pastel pinks and yellows. Images conjured up in my brain while reading were made concrete on the pages before me.

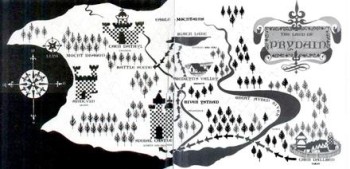

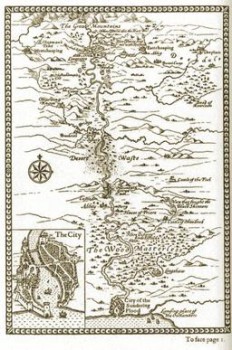

And, of course, I love maps in fantasy books. Always have, from those very first ones I saw in The Lord of the Rings and the Conan books. While Tolkien’s maps are intricate, lovingly created works of art, and the one of Hyboria is spare and undetailed, both intensify the illusion that the books’ worlds are real. They may not have been as vast and detailed as my dad’s atlas, but they were as captivating. While a book doesn’t need to include a map, I’m a fan of one that does. It’s an added bonus that I really dig. (To read another piece I wrote about maps several years ago, you can click HERE).

When it comes to mapping out a fantastic world, there are two major opposing views on the matter. Writing against explicitly laying out the longitude and latitudes of one’s world was M. John Harrison:

“Every moment of a science fiction story must represent the triumph of writing over worldbuilding. Worldbuilding is dull. Worldbuilding literalises the urge to invent. Worldbuilding gives an unnecessary permission for acts of writing (indeed, for acts of reading). Worldbuilding numbs the reader’s ability to fulfill their part of the bargain, because it believes that it has to do everything around here if anything is going to get done.

Above all, worldbuilding is not technically necessary. It is the great clomping foot of nerdism. It is the attempt to exhaustively survey a place that isn’t there. A good writer would never try to do that, even with a place that is there. It isn’t possible, & if it was the results wouldn’t be readable: they would constitute not a book but the biggest library ever built, a hallowed place of dedication & lifelong study. This gives us a clue to the psychological type of the worldbuilder & the worldbuilder’s victim, & makes us very afraid.”

At the opposite pole was Lester del Rey, that old marketer of the genre, in the foreword to J.B. Post’s An Atlas of Fantasy:

At the opposite pole was Lester del Rey, that old marketer of the genre, in the foreword to J.B. Post’s An Atlas of Fantasy:

“Certainly the reader of such tales is also in need of a map to help him follow the author through the course of the story. A good map brings the territory into sharp focus, giving it a sense of reality otherwise lacking. Without such a guide, the reader is often forced to attempt his own mental cartography, or remain hopelessly vague about much of the development of the story.”

Harrison’s remarks are clearly putting the onus on the artists, requiring them to describe their world in words, thereby summoning up images in their readers’ minds. For him, the worlds of story exist in the imagination, not charted out on graph paper.

Del Rey is speaking for the reader, or at least the lazier reader. It’s clearly of a part with his dislike for literary, or “hard”, writing, and of his desire to turn fantasy into a mass market consumer product. Without pictures, the reader will be lost.

His quote makes me immediately sympathize with Harrison’s perspective. Del Rey was intimating, no, outright declaring it’s too hard for a reader to follow adventures in a made-up land without a clear travel guide. Did he really think readers will get lost between the Lantern Waste and Cair Paravel? Or trekking through the Dreamlands? Does it even matter to the story actually being told? Is the writer’s true achievement — his or her words — too imprecise to conjure up coherent landscapes? It’s such an outrageous annoying statement it makes me furious, even though he said it forty years ago and he’s been dead for over twenty.

His quote makes me immediately sympathize with Harrison’s perspective. Del Rey was intimating, no, outright declaring it’s too hard for a reader to follow adventures in a made-up land without a clear travel guide. Did he really think readers will get lost between the Lantern Waste and Cair Paravel? Or trekking through the Dreamlands? Does it even matter to the story actually being told? Is the writer’s true achievement — his or her words — too imprecise to conjure up coherent landscapes? It’s such an outrageous annoying statement it makes me furious, even though he said it forty years ago and he’s been dead for over twenty.

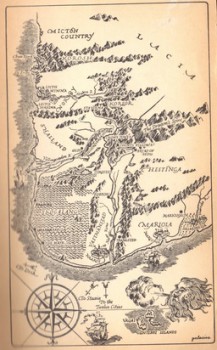

But then I calm down because, to loop back to my first sentence here, I’ve always loved maps. The Middle-earth and Hyboria maps blew my mind (and still do). I love gorgeous ones — like Rafael Palacios’ for The Well of the Unicorn (a book I haven’t even read) and James Cawthorn’s of Nehwon — but even the simple maps in the Riddle-Master of Hed and Stormbringer added a spark to these books when I first read them.

As little as I need a map, and fume about del Rey’s lack of faith in readers, fictional maps are intoxicating. I don’t need to see where Spiral Castle is in relation to Caer Dalben, as Lloyd Alexander does a splendid enough job of informing me by his words, but I love seeing it as much as I loved picking out the Beacons of Gondor or tracing Ged’s travels across Earthsea.

As little as I need a map, and fume about del Rey’s lack of faith in readers, fictional maps are intoxicating. I don’t need to see where Spiral Castle is in relation to Caer Dalben, as Lloyd Alexander does a splendid enough job of informing me by his words, but I love seeing it as much as I loved picking out the Beacons of Gondor or tracing Ged’s travels across Earthsea.

In an article he wrote several years ago Joe Abercrombie declared that he was probably in the “anti-map camp.” But while he felt them inappropriate for the character-driven stories he wrote, and more generally that an included map “can damage the sense of scale, awe, and wonder that a reader might have,” he wrote that if he had had to include them it wouldn’t have bothered him too much. They are an artifact of the genre deeply interwoven into it, and even he can imagine a day when he’d draw one himself. I understand and sympathize with Abercrombie, but I’m willing to risk finding a map at the front of a book I’m reading.

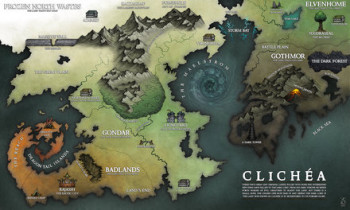

It’s easy to make fun of bad maps littered with unpronounceable place names, dark towers, and haunted ruins as Diana Wynne Jones does in her The Tough Guide to Fantasyland. Recently, one of the best satires of them, titled Clichéa, appeared courtesy of map designer Sarithus. Anyone who ever ran an RPG campaign has probably been guilty of creating just such a map. While funny, these don’t reflect something inherently wrong about maps, just bad writing and a lack of originality.

It’s easy to make fun of bad maps littered with unpronounceable place names, dark towers, and haunted ruins as Diana Wynne Jones does in her The Tough Guide to Fantasyland. Recently, one of the best satires of them, titled Clichéa, appeared courtesy of map designer Sarithus. Anyone who ever ran an RPG campaign has probably been guilty of creating just such a map. While funny, these don’t reflect something inherently wrong about maps, just bad writing and a lack of originality.

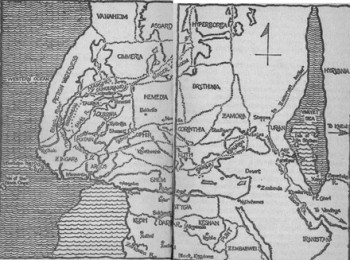

And maps have been a part of fantasy set in secondary worlds from the beginning. William Morris’ The Sundering Flood (1897) included one of the earliest and still most attractive ones. L. Frank Baum drew a colorful, if mis-oriented, one of Oz. Decades before the complexity of Middle-earth, writers were inspired to demarcate the borders of their make-believe lands.

And maps have been a part of fantasy set in secondary worlds from the beginning. William Morris’ The Sundering Flood (1897) included one of the earliest and still most attractive ones. L. Frank Baum drew a colorful, if mis-oriented, one of Oz. Decades before the complexity of Middle-earth, writers were inspired to demarcate the borders of their make-believe lands.

And writers have never looked back, for which I’m very grateful. Even if things did get a little out of hand in the wake of the gaming boom and Tolkien-clone era of the late 1970s and 80s, with way more detail and an explosion of cliches, I’ve never gotten tired of finding a map at the front of a new fantasy novel. For me, they’re not crutches for, or something that supplants, the words of the story, but something that augments them. It’s another bit of literary stagecraft that lets me suspend my disbelief just a little bit more and be transported just a little bit further into a created realm of fancy.

Let me know what you think. Do you need or want them, or should they be avoided at all cost? Which are your favorites?

This piece is intended to be neither a full blown exploration of the pros and cons of fantasy maps or their history. For that (and a tip of the hat to Matthew Surridge for telling me about it), you can go to The Map Room, a blog by Jonathan Crowe. It’s about all sorts of maps — real as well as fantastic — and will keep any map junkie spellbound for hours.

Oh, and I’ve included links to the maps I’ve mentioned but didn’t include here (except the one from Stormbringer which I couldn’t find).

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him. You can read his thoughts about epic high fantasy here.

What do you think of the notion of distinguishing between cartographic fantasy and topographic fantasy?

Cartographic fantasy features a map(s) of an imaginary realm. The reader is helped to “believe” in it by the map(s). Tolkien’s Middle-earth and Howard’s Hyborian World, which you mention, are examples of the cartographic fantasy.

Topographic fantasy might include a map supplied by the author — or the reader might get one from a dealer in maps; because topographic fantasy deals with real locations in our world, although the adventures are fantastic. Alan Garner’s The Weirdstone of Brisingamen is an example: you can buy a detailed Ordnance Survey contour map and follow the adventures of Susan and Colin in this Cheshire area (as I have done). Richard Adams’s Watership Down and The Plague Dogs would also qualify as topographic fantasy novels. In this category of imaginative fiction, the author’s fascination with a real landscape is likely to be communicated.

It might not always be easy to decide whether a book should be assigned to one or the other of these categories. Sterling Lanier’s little-known novel The War for the Lot, which he sent to Tolkien and which Tolkien seems to have appreciated, could be a topographic romance. It is set in this world and the reader will feel as if the author is working with a locale that Lanier knew. However, the book is vague enough that it may be the map illustrates an imagined location on our earth.

For more on “Topographic Romance” and “Cartographic Romance,” check Fancyclopedia III:

http://fancyclopedia.org/topographic-romance

http://fancyclopedia.org/cartographic-romance

Reference for Tolkien commenting on Lanier’s The War for the Lot:

http://www.betweenthecovers.com/btc/item/399812/

I’m a big fan of maps (and have an embarrassingly large collection of old RPG boxed sets that I’ll never play, but which I keep at least in part because of the maps), but I can see both sides of the “should they be included in the book” argument.

Having said that, I think that a map can be very helpful when writing the book, even if it’s just a piece of notebook paper with a jagged line for the coast, a couple of dots for cities, and maybe a river and some mountains. Makes it easier to avoid having the adventurers travel east from Aal to Bux and then return traveling east from Bux to Aal.

(Glen Cook had a passage in one of the

Oops. To continue:

Glen Cook had a passage in one of the later Black Company books that read like an in-world excuse for geographic inconsistencies between books — maybe when the distance between two places was given as two different numbers, they were using “local” miles, not standard, etc.

Historical atlases are a particular “trap” of mine, as I find it addicting to “watch” as a culture/language/polity appears, grows, shrinks, disappears. Practically a novel all on its own, in pictures.

As for the inclusion of maps in fantasy books, well, I have read books based on seeing maps in J.B. Post’s An Atlas of Fantasy, so maps do add to my enjoyment of the work. But, I can do without if the story is not really concerned with geographical or geopolitical features.

I love a map in a fantasy novel. That said, I’m leery of including a map in my secondary fantasy. Not being a graphic artist or cartographer, I’ve made very rough maps, just detailed enough to help me keep my details internally consistent. Heaven help the map artist who has to turn that jumbled mess into something a reader wants to use!

Major Wootton, I’ve also written contemporary fantasy that could be called topographic. Tales from Rugosa Coven is set in a specific county on the Jersey Shore, and while I worked on it I often drove to the settings I was using. I did need to call on a marine biologist friend to get the sailing bits right, and a friend who’d grown up in blueberry territory to get the Pine Barrens right. I’d have put gravel roads. For that book I figured that populating my New Jersey with ghosts, merpeople, and the Jersey Devil was enough fudging, and I might as well get everything else right.

@Major Wootton – Thanks for the links. I hadn’t thought about that for this and I’m disappointed I didn’t. I love the thought of Alan Garner being so in love with the real Alderley Edge is led to finding a fantastical world within its bounds.

I’m very sad I didn’t spring for a copy of War for the Lot 20 years ago.

@Joe H – The full Harrison essay is a long discussion of the nature of creating an imaginary world and the interaction between the reader and the text. I agree with some of it, but I still love a good map.

@Eugene R – I’ve tracked the history of the Balkans across the various atlases I own, watching the rising and falling tides of the Ottomans, the Austrians, and finally Yugoslavia.

@Sarah A – I get your wariness. It’s a rare author with the artistic and cartographic skills of Tolkien or PC Hodgell (someone I should have included).

I often wonder whether this idea for a map of the world of a particular novel stems from Thomas Hardy. Hardy’s Wessex is a fictionalised depiction of southern, particularly south western, England. The maps that adorn his books show a recognisable England with the Wessex place names. The game is then to identify the fictional places with the real ones – thus the fictional Casterbridge is the actual Dorchester, Christminster is Oxford and so on. Hardy was not a fantasy writer – although he did write a couple of spooky stories – but his fictionalisation of English landscape does seem to hover somewhere between the topographic and cartographic fantasy types.

Of course, the other great map to illustrate a book was that of Treasure Island. In Stevenson’s case, the map came first and the story afterwards.

Maps! The map and the territory. A fascinating subject and a good article on it. However, I think you are conflating two different things between your quotes from M. John Harrison and Lester Del Rey. Harrison isn’t talking about maps so much as he’s talking about worldbuilding. Worldbuidling often includes maps, but it certainly isn’t isolated to that.

My views on this are skewed a bit by my editorial experience at Heroic Fantasy Quarterly. Clearly, in the short-fiction world maps usually play no part, but worldbuilding surely does— and almost always (as ?? says)it is to the story’s detriment. It’s a grisly fact that worldbuilding is like salt, you need a little bit, but too much is just too much. Most writers put a decent amount of work into worldbuilding, but novice writers often seem to need to ensure that their work is acknowledged by putting on the page. Worse yet, worldbuilding is often expressed via backstory—a horrid incestuous relationship for short fiction if there ever was one!

As for the big maps of fantasy, they are a curious thing. To take the LORD OF THE RINGS, this giant two-page map is nice for the reader, but for the travelers themselves it doesn’t matter much. in fact I’d say that although they have a map in THE HOBBIT, they really don’t seem to have on in LOTR at all. It’s all follow the road, trust that Aragorn knows how to get over the mountains. Push through the woods in that direction and hope the elves living there don’t murder you. Follow the big river. Better to die in the trackless forest than face whatever the Urik Hai have in store for you. Trust that Gollum knows how to get to Mordor. Trust that Treebeard knows his way around. I suppose if we’re all gonna die at the Black Gate we might as well follow the road there.

Maps are, perhaps, a clever way to work in worldbuilding. Literally, a picture is worth a thousand words, and a map is a picture. If properly deployed it very subtly secures an acknowledgement from the reader of the author’s worldbuilding efforts. Frodo doesn’t really need to know about the realms to the far south and northeast, and neither does the reader—but a glance at a map shows the reader that there are realms to the northeast and the south. A glance and then it’s over, but if another thousand words had been poured in? Tedium!

All that said, I think it is interesting that one of the most successful fantasy series of the last twenty years—Harry Potter—has only like one map in any of the books (the one showing Hogwarts, the Whomping Willow, the secret passage, and … I can’t remember, the town?). Of course, Hogwarts itself constantly changes shape, and most wizards simply teleport or fly wherever they want to go so… a map for the reader is thus nigh impossible to do. At least for us muggles. The Marauders Map that Harry inherits can track the moving rooms of Hogwarts.

Rowling! Always a step ahead.

@Adrian – I admit I did use Harrison’s quote for my own purposes even knowing his full piece has a whole lot else going own. Still, I think it’s essentially dealing with not wanting to make things so fixed, so clear for readers that all they have to do is ingest predigested bits. World building does involve more than just maps, but they are the most visible part of it.

You make a great point about the LotR which bolsters one of my points that the map exists to augment the readers’ imagination. It really doesn’t serve any purpose or even necessarily exist for the characters.

It’s my current interest in epic high fantasy that triggered this. Other than Conan or something like the limked Dorgo the Dowser collection the only S&S short story anthology I know of with maps is, I think, one of L S deCamp’s.

I wonder if Rowling’s lack of maps is related to her series’ roots in so many other genres without fantasy’s penchants for the things (mysteries, school novels, etc.).

@Neil – Sadly, I was only thinking of fantasy, but you raise an interesting point regarding Wessex. My research tells me he had sketched it out as early as 1881, but when did Trollope map Barsetshire?

I have read a fair few of Trollope’s novels but was not aware that a map of Barsetshire existed, so I Googled it. It seems he constructed a map when writing Framley Parsonage, published 1861. The Trollope Society of USA have a page with various reconstructions of that map, but not the original.

http://www.trollopeusa.org/map-of-trollope%C2%B4s-barsetshire/

I am not sure that a map of the county would really have enhanced my reading of the novels.

A different matter when it comes to Earthsea where cultures are shaped as much by their geography as anything else. Visiting each different island gives an insight into a different way of life. Looking at the map, seeing the location of the island, enhances the reading experience. Knowing where a particular country estate is, in relation to the town of Barset, for example, is just information and adds nothing to the story.

I’m reading two books currently. One, Gary Jennings’ Aztec has about three pages of maps in it — it’s not fantasy, but a straight historical novel set just before & during the Spanish conquest of Mesoamerica. Maps are great!

The other, Sorcerer of the Wildeeps (it’s what I read on my phone or Kindle when I can’t haul a 750 page trade paperback with me) doesn’t have any maps; but so far, the journey seems to be pretty linear, so perhaps not needed.