Beyond the Immediate Shiver: The Rim of Morning by William Sloane

According to either Google or Oz the Great and Powerful (I forget which, and for God’s sake, don’t look behind that curtain!), over 300,000 books are published in the United States every year. That’s over 800 a day, every day, day in and day out.

According to either Google or Oz the Great and Powerful (I forget which, and for God’s sake, don’t look behind that curtain!), over 300,000 books are published in the United States every year. That’s over 800 a day, every day, day in and day out.

Most, of course, are utterly worthless and are destined to vanish without a trace almost immediately (see Sturgeon’s Law), and given the magnitude of this never-ceasing flood of words, even worthy books by fine writers will inevitably go out of print sooner or later — most likely sooner.

But here’s the thing — even when they drop out of print, books that are good enough are remembered, and sooner or later, like Marely’s Ghost or that particularly embarrassing anecdote that your mother loves telling at every family gathering (especially when a new significant other is present), the good ones come back.

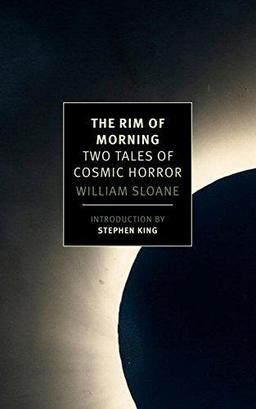

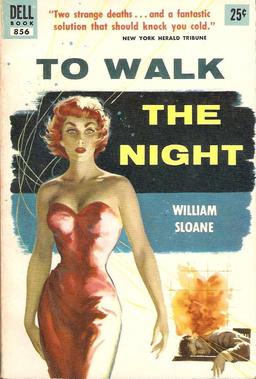

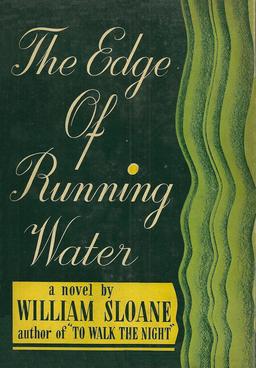

Hence The Rim of Morning: Two Tales of Cosmic Horror, an omnibus volume reprinting two novels that William Sloane wrote a long time ago: To Walk the Night (1937) and The Edge of Running Water (1939). The books have been reprinted a few times, mostly in paperback, over the more than seventy five years since their first appearance, but the last editions were over thirty years ago under the Del Rey imprint (see the hardcover and paperback editions in a previous BG post here.)

Sloane was not exactly prolific; the two novels collected here are the only ones he ever wrote (or are at least the only ones that were ever published; I for one am hoping that there’s a big trunk somewhere, stuffed with manuscripts that he never bothered to mail in.) Shortly after writing them, Sloane launched a literary career of impressive solidity, especially coming from a man who had mostly given up writing himself. He started his own publishing house, edited a pair of science fiction anthologies, taught at the prestigious Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference for over twenty five years, and eventually became the managing director of Rutgers University Press, a position he held until his death in 1974.

[Click on the images for bigger versions.]

[Click on the images for bigger versions.]

Which is all well and good, but why are his musty dusty old novels back in print now, seeing that they’re the solitary productions of a young writer who wrote so little and so long ago that he’s essentially unknown and who quickly gave up fiction for editing and publishing? Why are they vying for attention with the trendy productions of the early twenty first century, all the young adult supernatural romances, the zeppelin-powered steampunk visions, the military SF sagas, the multivolume fantasy epics, the endless mashups? Because they’re damned good, that’s why — they’re far too good to go away.

So…what’s the big deal? What do we have here?

In To Walk the Night, college friends Bark Jones and Jerry Lister drop by their old school to visit a former teacher, Dr. LeNormand, only to find that he has been murdered in strange and inexplicable circumstances. Just as surprisingly, they discover that this man, a confirmed bachelor and professor of theoretical mathematics, had recently married a stunningly beautiful young woman, and when they meet his widow, Selena, Jerry instantly falls in love with her. Bark, however, does not share his friend’s admiration; he is at first uneasy around Selena, and this disquiet quickly turns into positive dislike.

Before long, he realizes that his feelings go beyond simple jealousy or animosity; he is actually terrified of this strange woman – who never, in even the slightest way, speaks about her family or her past… who seems to literally read minds… who is ignorant of some of the most basic facts of everyday human life…who is startlingly intelligent, but who is cold, affectless, somehow utterly detached from any kind of normal emotion…and who sometimes seems to be slyly, condescendingly amused by all the silly people around her and their brief, transient lives, people she coolly observes without ever in any way getting close to.

When Jerry marries Selena and moves to a remote part of New Mexico to work on completing Dr. LeNormand’s mathematical theories, the same theories the late professor was working on at the time of his still-unsolved murder, Selena is displeased, and Bark’s fear becomes overpowering. After Bark’s misgivings are validated when events culminate in a shocking tragedy, he confronts Selena and gains an enigmatic answer or two to his questions, answers that leave him more frightened and desolate than he was before receiving them.

When Jerry marries Selena and moves to a remote part of New Mexico to work on completing Dr. LeNormand’s mathematical theories, the same theories the late professor was working on at the time of his still-unsolved murder, Selena is displeased, and Bark’s fear becomes overpowering. After Bark’s misgivings are validated when events culminate in a shocking tragedy, he confronts Selena and gains an enigmatic answer or two to his questions, answers that leave him more frightened and desolate than he was before receiving them.

In The Edge of Running Water, Richard Sayles travels to the isolated town of Barsham Harbor to visit his old college teacher and friend Julian Blair. Blair, a brilliant physicist, has cut himself off from the world after the death of his wife Helen. Holed up in his house with Helen’s younger sister, Anne, the housekeeper Mrs. Marcy, and a formidable woman named Mrs. Walters, Blair spends most of his time locked away in his lab, working on some momentous project that he isn’t willing to talk about. In his absence, the household is run by Mrs. Walters, who has an iron will and a hidden agenda of her own.

Things come to a head when the housekeeper is murdered under mysterious (in fact, impossible) circumstances and Richard discovers what Julian’s secret project is — obsessed with the loss of his wife, he is working on a machine that will (he hopes) enable him to communicate with the dead. It turns out that the device is indeed able to do something extraordinary, but it has nothing to do with spirit communication. Blair’s machine may, in fact, have the power to destroy the world. It just avoids doing so in an ending that is spectacular, terrifying, and awe-inspiring in equal measure.

The Edge of Running Water has all of the metaphysical allusiveness and dread inducing mood of the first book along with a dash of atmosphere that’s straight out of Arkham or Innsmouth; the insular locals are very good at making people from “outside” feel very unwelcome, and Herbert West or Randolph Carter would recognize a kindred spirit in Julian Blair. The characterization in this second novel is very fine, especially that of the sinister and enigmatic Mrs. Walters, a person vivid and intriguing enough to live on in the memory well past the end of the story.

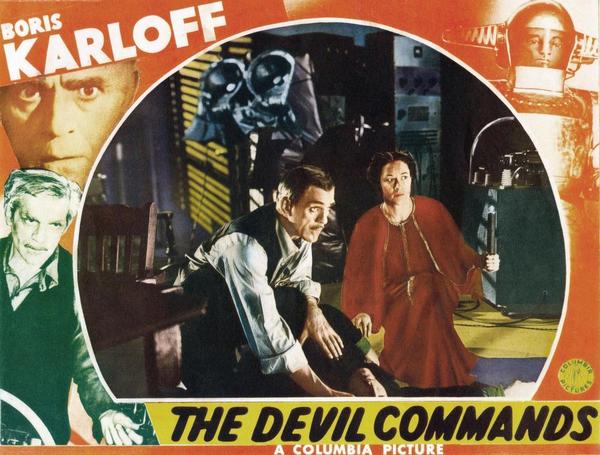

The novel was adapted — loosely — for a 1941 Boris Karloff quickie, The Devil Commands.

The subtitle of this omnibus edition labels these books Two Tales of Cosmic Horror. If cosmic horror is fear deriving from an apprehension of our smallness and ignorance and powerlessness in an immense and incomprehensible and (at best) indifferent universe, then what we have here is cosmic horror par excellence.

Sloane’s pair of nightmares would have scared the hell out of Blaise Pascal (who, had he lived 250 years later, would surely have written for Weird Tales), who said, “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me,” and H.P. Lovecraft, who declared,

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Sloane’s protagonists confront those infinite spaces and get the barest hint of the correlation of their contents… and the terrifying vistas of reality thus revealed almost drives them insane.

To Walk the Night and The Edge of Running Water are startlingly good books, and they have a unique flavor, a flavor that retains all of its eerie, disturbing quality even after the many years that have passed since William Sloane first wrote them. Today we live in an era of extreme and sometimes reckless genre blending, so we’re not startled by seeing Abraham Lincoln battling vampires or by encountering magic realism in the Old West, but Sloane’s combinations feel more organic and less forced than those found in many of today’s books.

He found a way to seamlessly combine the horror, mystery, and science fiction genres in a way no one else ever has; he pits the conventions and expectations of one genre against those of another in ways that constantly keep a reader off balance, and that keep you unsettled and jumpy right up until the end. What’s even more unusual, he had a very fine (and very rare) quality, especially in horror/SF writers: judiciousness. Better than perhaps any writer in these genres I’ve ever read, Sloane knew exactly how much to reveal and exactly how much to leave a mystery. He manages his endings beautifully, avoiding the letdown of anticlimax and leaving the reader (this one, anyway) perfectly satisfied.

It’s a major loss to fantastic fiction that William Sloane wrote only these two novels; I could happily read a dozen more like them. The stories you’ll find in The Rim of Morning are genuinely frightening and disquieting, in ways that are both visceral and conceptual. They’re literally haunting; you’ll find yourself thinking about them long after you’ve read the last page, and they’ll give you a deep down chill that will stay with you well beyond the immediate shiver.

Thomas Parker’s last article for Black Gate was A Prophet Without Honor: J.G. Ballard.

Excellent review (as usual). I appreciate your focus on Sloane’s subtle yet inexorable building or suspense and horror, and his fine characterization, especially of Mrs. Walters–a character I wanted to despise, yet couldn’t by the end of the novel.

Sloane assumed his readers were intelligent enough to discern his subtleties, a quality that probably made him an excellent editor, I, too, wish he’d written more novels.