Wandering the Worlds of C.S. Lewis, Part II: Spirits in Bondage

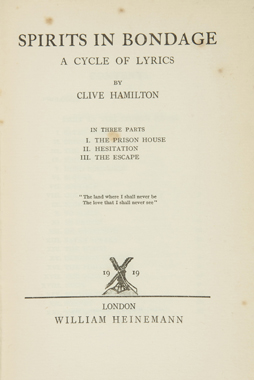

Yesterday I began a series of posts looking at the fiction of C.S. Lewis. Lewis has an unusually varied body of work, and I intend to wander through it chronologically and see what leaps out at me. I started with Lewis’ childhood tales of Boxen. Tomorrow I’ll take a look at his long poem Dymer. Today, I want to go through Lewis’ first book, a collection of lyric poems called Spirits in Bondage, published in 1919 when Lewis was still an atheist.

Yesterday I began a series of posts looking at the fiction of C.S. Lewis. Lewis has an unusually varied body of work, and I intend to wander through it chronologically and see what leaps out at me. I started with Lewis’ childhood tales of Boxen. Tomorrow I’ll take a look at his long poem Dymer. Today, I want to go through Lewis’ first book, a collection of lyric poems called Spirits in Bondage, published in 1919 when Lewis was still an atheist.

Yesterday I quoted Lewis’ judgement in his 1955 autobiography Surprised by Joy that the Boxen tales are novelistic and not poetic. If that’s so, what did the older Lewis think about the poetry he wrote in his youth? Did he find wonder and romance in the verse of Spirits in Bondage and Dymer? Hard to judge. Lewis doesn’t mention either volume in Surprised by Joy. Which strikes me as a little odd.

That book — again, published almost thirty years after Dymer, and twenty-five years after his conversion — describes his attempt to recapture a specific sense of imaginative joy. Lewis concludes that the emotion he felt was a kind of signpost directing him to God — that the ‘joy’ he felt and later sought came from feeling a specific kind of desire, of which God was the object. He also says that “I do not think the resemblance between the Christian and the merely imaginative experience is accidental,” and associates his experience of joy with myth and poetry as well as nature. Though Lewis states that his Boxen stories had nothing to do with that kind of inner experience, one might think his poetry at least would have a direct bearing on the subject. In fact, though, he mentions going through a kind of reaction against myth and the fantastic at about the time Spirits in Bondage was published and in the years after — “a retreat, almost a panic-stricken flight, from all that sort of romanticism which had hitherto been the chief concern of my life.” Given that, what does Spirits look like?

It’s dispirited, overall, and indeed frequently dis-spirited in the fullest sense. It’s filled with mythic images, but there’s often a consciousness of inadequacy about the myths. The book begins with a verse prologue, in which Lewis likens himself to “Phoenician men, to the Tin Isles sailing” — that is, to Britain, where in antiquity Phoenicians traded for tin. The sailors he imagines

It’s dispirited, overall, and indeed frequently dis-spirited in the fullest sense. It’s filled with mythic images, but there’s often a consciousness of inadequacy about the myths. The book begins with a verse prologue, in which Lewis likens himself to “Phoenician men, to the Tin Isles sailing” — that is, to Britain, where in antiquity Phoenicians traded for tin. The sailors he imagines

Chaunted loud above the storm and the strange sea’s wailing,

Legends of their people and the land that gave them birth —

Sang aloud to Baal-Peor, sang unto the horned maiden,

about the treasure they’ll find. This singing moves the rowers at work below so that they “forgot their burden in the measure of a song,” with the result that “the merchants and the masters and the bondsmen all together, / Dreaming of the wondrous islands, brought the gallant ship along” — as Lewis now promises to “sing of lands unknown,” imagining himself “flying” from a “scarlet city” and a pitiless Lord on an iron throne mocking broken people praying all about him.

It’s an odd prologue, not so much for the anti-theism implied by the image of the throned tyrant as for the extended metaphor of Phoenician traders. Lewis promises to write of myth, but his central image is a set of merchants on the make (aiming for what is now England, incidentally, not Lewis’ Irish home). The rowers hard at work are relieved by song, but it’s a song about their bosses getting rich. Lewis concludes the poem by literally promising a personal escape, fleeing the scarlet city “to a port that none has seen.” It’s an escape for him alone; he’s already at sea. His song won’t help anyone else. Add it all up, and there’s a sense to me that while Lewis has found some images and a general approach that mean a lot to him, he’s not quite in control of his imagery.

Three sections follow the prologue: “The Prison House,” “Hesitation,” and “The Escape.” The first poem proper, “Satan Speaks,” has Satan declaring himself to be “Nature, the Mighty Mother,” then giving a list of further evils with which the hermaphroditic devil identifies, as for example: “I am the flower and the dewdrop fresh, / I am the lust in your itching flesh.” It’s a little like the list of natural forms in the early Irish “Song of Amergin” (which begins, in Thomas Rolleston’s 1911 translation, “I am the Wind that blows over the sea, / I am the Wave of the Ocean; / I am the Murmur of the billows;” Robert Graves would later begin his translation “I am a stag: of seven tines, / I am a flood: across a plain, / I am a wind: on a deep lake”). But what mainly strikes me is Satan declaring “I am the fact and the crushing reason / To thwart your fantasy’s new-born treason.” Coming among a series of images representing natural law, the lines emphasise Lewis’ sense of the imagination in chains, of moral censors declaring the imaginative to be wicked or forbidden. On the other hand, Lewis, passionate about Norse myth from an early age, ends the poem with Satan declaring himself to be “the wolf that follows the sun” — as, in Norse myth, a wolf follows the sun to swallow it at the time of the final battle. It’s a nicely syncretic image, but undercuts the naturalism Satan proclaims in the rest of the poem.

Three sections follow the prologue: “The Prison House,” “Hesitation,” and “The Escape.” The first poem proper, “Satan Speaks,” has Satan declaring himself to be “Nature, the Mighty Mother,” then giving a list of further evils with which the hermaphroditic devil identifies, as for example: “I am the flower and the dewdrop fresh, / I am the lust in your itching flesh.” It’s a little like the list of natural forms in the early Irish “Song of Amergin” (which begins, in Thomas Rolleston’s 1911 translation, “I am the Wind that blows over the sea, / I am the Wave of the Ocean; / I am the Murmur of the billows;” Robert Graves would later begin his translation “I am a stag: of seven tines, / I am a flood: across a plain, / I am a wind: on a deep lake”). But what mainly strikes me is Satan declaring “I am the fact and the crushing reason / To thwart your fantasy’s new-born treason.” Coming among a series of images representing natural law, the lines emphasise Lewis’ sense of the imagination in chains, of moral censors declaring the imaginative to be wicked or forbidden. On the other hand, Lewis, passionate about Norse myth from an early age, ends the poem with Satan declaring himself to be “the wolf that follows the sun” — as, in Norse myth, a wolf follows the sun to swallow it at the time of the final battle. It’s a nicely syncretic image, but undercuts the naturalism Satan proclaims in the rest of the poem.

The tensions of “Satan Speaks” are echoed in the next poem, “French Nocturne (Monchy-Le-Preux).” Lewis apparently recalls his wartime experiences here, describing a French village ruined in the war, a blasted and demythologised landscape where even the Moon is only “a stone that catches the sun’s beam.” Lewis, who had been briefly dreaming of a lunar wonderland, declares “I am a wolf,” and gives up dreaming to return to a world where he and his fellow soldiers “can bark for slaughter: cannot sing.” It’s one of the most powerful pieces in the book, and its placement here helps: with Satan having just identified himself as a wolf, Lewis’ similar declaration both links himself to sin, and yet also implies that in this mythless state even the idea of Satan is just a poetic fancy.

At any rate, it sets the tone for much of what follows. “A Satyr” describes its subject with lyricism midway between Swinburne and psychedelic rock, concluding with the satyr apparently unable to catch fleeing nymphs; “Victory” describes mythic heroes dead and gone, stating that “ancient songs … wither as the grass” — although here the “yearning, high, rebellious spirit of man” can strive “with red Nature” and “the beast become a god.” The implication is that new songs, new myths, might be made. Yet for the most part Lewis insists on the limits of myth. Here myth’s described, in the final stanza of “Apology”:

All these were rosy visions of the night,

The loveliness and wisdom feigned of old.

But now we wake. The East is pale and cold,

No hope is in the dawn, and no delight.

“Ode For New Year’s Day” imagines a God in order to curse him (“him” is uncapitalised in the text) and blame him for the death of goodness; again this poem imagines a golden age of myth in the past opposed to the new age of the present, again Lewis yearns for an escape to the forests of “some other country beyond the rosy West”. On the other hand, a second poem called “Satan Speaks” (appropriately, the thirteenth of the book) imagines dreams and the desire for myth as a Satanic trap.

“Ode For New Year’s Day” imagines a God in order to curse him (“him” is uncapitalised in the text) and blame him for the death of goodness; again this poem imagines a golden age of myth in the past opposed to the new age of the present, again Lewis yearns for an escape to the forests of “some other country beyond the rosy West”. On the other hand, a second poem called “Satan Speaks” (appropriately, the thirteenth of the book) imagines dreams and the desire for myth as a Satanic trap.

Still, the poems read as though Lewis was too instinctively drawn to the mythic to consistently portray an unmagical world. For example, in “The Witch” Lewis depicts a red-haired witch, a worshipper at a “Druid stone,” defeated by Christian counter-magic and burned. It’s a tragic story, but the tragedy he gives us is a morally blind but metaphysically powerful mythology destroying a belief more open to wonder, not a tragedy coming from the falsity of all mythologies: “The bishop’s brought her strongest spell / To naught with candle, book, and bell.” That’s all in keeping with the then-current theories of witch-cults and primal mother-goddesses (reflected in fictions like Algernon Blackwood’s “Ancient Sorceries,” which Lewis enthused over in letters written in 1916), though Lewis calls his witch a “maid” rather than imagine her as a typical fertility worshipper. But more importantly, I think, Lewis insists that his witch is a visionary; her “quivering will she sent / Alone into the great alone / Where all is loved and all is known.” But as a visionary, she’s now being destroyed by a “mob” made up of “the bishop’s court,” of “city oafs,” of “full-fed burghers.”

Similarly “Dungeon Grates” describes a glimpse of the numinous, what one sees through the grates locking us in the physical world. “The Philosopher” praises the wisdom of youth’s “lustyhead.” “The Ocean Strand” is a place where it’s possible to see a nereid. Lewis frequently depicts the sea and the seaside as venues for escapes into myth, going back to the sea voyage of the prologue, but then again poems like “Noon” and “The Autumn Morning” are unironic praises of the natural world he elsewhere affects to despise.

The three poems of Part II, “Hesitation,” have a similar ambiguity. “L’Apprenti Sorcier,” the sorcerer’s apprentice, hesitates to follow spirits into a mythic world because he fears that world’s dangers. “Alexandrines” describe inevitability, and the inevitability of death, while “In Praise of Solid People” is a heavily ironic appreciation of those who “are not fretted by desire” for unrealisable dreams, unlike the poem’s speaker, who describes a late night haunted by visions of things beyond his grasp. The last and most potent of these visions is of “dusky galleys” sailing “on a faerie sea”. Again, recalling the prologue, the sea is an escape — or would be, except the dream vanishes, leaving the speaker “no nearer the light” and “no further from myself,” which last I find an interesting phrase. It implies that Lewis wants to get away from his own consciousness; that the images of fantastic escape he’s struggling with aren’t really being smothered by the world as it is, but by his own selfhood.

“Escape” is in fact the titular concern of the final sixteen poems of the book, and it’s interesting that the first line of the first poem of this section, “Song of the Pilgrims,” contains the phrase “at the back of the North Wind.” That’s the title of a book by Victorian fantasist George MacDonald, one of the writers Lewis most admired. MacDonald’s evoked here in search of escape, the escape offered by fantasy and myth. It’s worth pointing out the escape Lewis writes of in these poems is to be sharply distinguished from “escapism” as it’s commonly meant (the word, with its current meaning, wouldn’t be coined until the early 1930s); Lewis is here seeking a healing escape, a necessary escape — as it were an escape from a spiritual depression. So Lewis’ singing pilgrims seek the “Dwellers at the back of the North Wind,” who live in a paradise on earth, and maintain their faith however much they wander. But not a faith in God, or only incidentally in God. Their faith is in the Dwellers, and their paradisical home. It’s a faith in Romance, in wonder, doubting yet persevering in the face of all experience to the contrary.

“Escape” is in fact the titular concern of the final sixteen poems of the book, and it’s interesting that the first line of the first poem of this section, “Song of the Pilgrims,” contains the phrase “at the back of the North Wind.” That’s the title of a book by Victorian fantasist George MacDonald, one of the writers Lewis most admired. MacDonald’s evoked here in search of escape, the escape offered by fantasy and myth. It’s worth pointing out the escape Lewis writes of in these poems is to be sharply distinguished from “escapism” as it’s commonly meant (the word, with its current meaning, wouldn’t be coined until the early 1930s); Lewis is here seeking a healing escape, a necessary escape — as it were an escape from a spiritual depression. So Lewis’ singing pilgrims seek the “Dwellers at the back of the North Wind,” who live in a paradise on earth, and maintain their faith however much they wander. But not a faith in God, or only incidentally in God. Their faith is in the Dwellers, and their paradisical home. It’s a faith in Romance, in wonder, doubting yet persevering in the face of all experience to the contrary.

Poem XXVI, “Song,” insists that the “atoms dead” of the material world may be beautiful but only because they form a veil hiding a more beautiful world of spirit. The first draft of the poem was written in May, 1918, while Lewis was in a hospital recovering from his war wound; it insists on the presence of faeries and tritons, and on satyrs with “laughing broods.” Myths are fruitful in this song, promising a heavenly garden where “the Other People go.” Lewis would write a prologue to Dymer in 1950 in which he said that images of gardens and paradisical bowers were very powerful to him; the “Song” is a personal song of hope. In a letter he wrote to his friend Arthur Greeves discussing the first draft of the poem, Lewis said that “the conviction is gaining ground on me that after all Spirit does exist; and that we come in contact with the spiritual element by means of these ‘thrills.’ I fancy there is Something right outside time & place, which did not create matter, as the Christians say, but is matter’s great enemy: and that Beauty is the call of the spirit in that something to the spirit in us.”

Many of the other poems in this section describe hard-won and usually personal salvation from strict materialism. The speaker of “Ballade Mystique” lives alone and sees “Immortal shapes of beauty clear.” The speaker of “Night” hears “faerie voices.” “Oxford” describes the city as a rejection of the “brute” part of humanity: “The Spirit’s stronghold — barred against despair.” There is a sense of crisis resolved through Romanticism, and “Hymn (For Boys’ Voices)” occasionally reaches a kind of near-Blakean height:

Every man a God would be

Laughing through eternity

If as God’s his eyes could see.

Lewis also has a poem called “The Ass,” recalling one of Coleridge’s more unfortunate titles. At worst, there’s a similar kind of over-enthusiasm in this section. Notably, he avoids presenting any answer to the (admittedly melodramatic) problems of the earlier poems. A piece like “Hesperus” is a simple praise of the star and demigod, ignoring the crisis of faith of the earlier poems. Lacking the sense of conflict with the world of the other poems, Part III is generally flat. Salvation comes about not by an effort of the poet, but by the exertion of magical or divine forces that catches the poet up. In the “Hymn” God becomes a good Orpheus-like figure with a song that can captivate “men and beasts” and draw them to “the widening morn,” which is “the Hidden Land” where we can “grow immortal.” The poem thus reverses the trend of the rest of the poems; and it’s interesting to read bearing Lewis’ later life in mind, when he would describe his conversion as almost unwilling — like one of the unwilling followers of this Orpheus-God. It is perhaps possible to read this book of poems as unwittingly illustrating the story he would go on to live: a depressed spirit who is drawn by external forces into a more magical and meaningful world.

Lewis also has a poem called “The Ass,” recalling one of Coleridge’s more unfortunate titles. At worst, there’s a similar kind of over-enthusiasm in this section. Notably, he avoids presenting any answer to the (admittedly melodramatic) problems of the earlier poems. A piece like “Hesperus” is a simple praise of the star and demigod, ignoring the crisis of faith of the earlier poems. Lacking the sense of conflict with the world of the other poems, Part III is generally flat. Salvation comes about not by an effort of the poet, but by the exertion of magical or divine forces that catches the poet up. In the “Hymn” God becomes a good Orpheus-like figure with a song that can captivate “men and beasts” and draw them to “the widening morn,” which is “the Hidden Land” where we can “grow immortal.” The poem thus reverses the trend of the rest of the poems; and it’s interesting to read bearing Lewis’ later life in mind, when he would describe his conversion as almost unwilling — like one of the unwilling followers of this Orpheus-God. It is perhaps possible to read this book of poems as unwittingly illustrating the story he would go on to live: a depressed spirit who is drawn by external forces into a more magical and meaningful world.

Perhaps. I find even this retrospective attempt to make sense of the order of the book has problems. I can’t find a coherent sequence to the order of the poems. Lewis was always alert to the role of convention in poetry, and perhaps these poems were written as exercises — the emotions exaggerated, if not adopted strictly for the sake of performance. Whatever the case, as a whole the result strikes me as incoherent. Nothing’s communicated; there’s no consistent approach to the world that I can find, and if the use of myth is at least the great commonality of the poems, there’s no clear sense of what myth is to be used for.

There are certainly elements in this volume one does not normally associate with the later Lewis. The startling praise of a witch’s pagan magic over Christianity springs to mind. But more deeply, as in the letter I quoted above, there’s a sort of gnostic sense recurring in these poems; a sense of the material world as a prison barring the human spirit from a higher spiritual reality beyond. It’s also interesting that several of the poems not only use Celtic myth but are also strongly associated with Ireland — Lewis was still returning to Ireland regularly to visit his family, but had been living in England for years. A poem like “How He Saw Angus the God” seems to aspire to a Yeatsian mood, although it lacks the strangeness and absolute precision of Yeats.

There are certainly elements in this volume one does not normally associate with the later Lewis. The startling praise of a witch’s pagan magic over Christianity springs to mind. But more deeply, as in the letter I quoted above, there’s a sort of gnostic sense recurring in these poems; a sense of the material world as a prison barring the human spirit from a higher spiritual reality beyond. It’s also interesting that several of the poems not only use Celtic myth but are also strongly associated with Ireland — Lewis was still returning to Ireland regularly to visit his family, but had been living in England for years. A poem like “How He Saw Angus the God” seems to aspire to a Yeatsian mood, although it lacks the strangeness and absolute precision of Yeats.

Overall there seems to me to be little influence from other poetic voices of the era. The verse structures here are highly traditional in rhyme and metre; I mentioned Swinburne a few paragraphs ago, and the lush pseudo-Romantic imagery reminds me of him more than anyone else, especially in the handling of the sensuality of Classical myth. I suspect that even in 1919 this book would have seemed old-fashioned.

At any rate, however ambiguous, myth here presents a store of images the poet turns to again and again. Myth promises a way to escape common reality, which the poet seems to consider as of prime importance — at least, to judge by the structure of the early part of the book. Yet myth alone seems most often not to be enough. Myth can’t consistently bring the salvation the poet seeks, at least in the moment the lyric describes. And these are lyrics, usually with no real dramatic development of incident in these poems. They’re reflective, not usually narrative. There’s no real attempt to enact a myth, or to create a new mythology. That would come later, with Dymer.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy a collection of his essays for Black Gate, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] “Wandering the Worlds of C.S. Lewis, Part II: Spirits in Bondage” […]